Volume V, Issue 9

Author: E.B. Havell

Editor’s Note: We feature below some excerpts from a lecture delivered by E. B. Havell at Chaitanya Library, Calcutta (now Kolkata), in December 1905. The timely relevance of the key points mentioned in this lecture is truly remarkable, despite the references to the context of his time. If anything, the challenges that he points out — mindless imitation of the Western styles, commercialism and lack of higher motive in creating Art — have become even bigger since the time this lecture was delivered.

Sri Aurobindo has spoken of the immense value of the efforts of E. B. Havell and the work of the new school of Indian art he helped establish in Bengal in bringing about an important change in the aesthetic standpoint of Western critics of Indian art. At one place he writes:

“The art of India contradicted European notions too vitally to be admitted into the European consciousness; its charm and power were concealed by the uncouthness to Western eyes of its form and the strangeness of its motives and it is only now, after the greatest of living art-critics in England had published sympathetic appreciations of Indian art and energetic propagandists like Mr. Havell had persevered in their labour, that the European vision is opening to the secret of Indian painting & sculpture.

~ CWSA, Vol. 12, p. 392

For the ease of online reading, we have made a few formatting revisions and also added appropriate headings.

Art – Ornamental or Useful?

Perhaps one of the greatest difficulties which artists and art teachers meet with in the present day arises from the popular view of art as something separate from, if not altogether opposed to practical use. Any student of art will soon realise that this is entirely contrary to all the teaching of art tradition and history. But nevertheless it is one which has a firm bold upon public opinion; especially in Europe where within the last two centuries the old artistic traditions have been superseded by a new order of things, which has not yet had time to adjust itself to national needs.

In India, too, under the British administration this idea has taken firm root. And its influence is conspicuous in most of the institutions, educational and administrative, which India has borrowed from Europe. Indian Universities, faithfully imitating their European models, exclude art from their curriculum, treating it as a non-essential factor in national culture. […]

Indian art has come to be regarded either as a beautiful relic of antiquity for which no place can be found in modern life, or as a curiosity made chiefly for the delectation of our cold-weather visitors from Europe. It is one of these superfluities which we never consider essential either for our spiritual or material well-being. But when it does come into our life, it is only when we have satisfied what we are pleased to consider our practical requirements. In other words, art is regarded as something essentially ornamental, rather than useful.

Intimate Association of Beauty with Use

If it be true that art has really, in the present day, entered upon a new phase in which it ceases to play an essential part in our national life, it must inevitably follow that art, as we take it, must sooner or later cease to exist; for there is no natural law more sure in its working than the one which ordains the extinction of everything which no longer serves its intended use in the cosmos. A muscle in our bodies which is never exercised soon becomes atrophied and incapable of use. Creatures which are deprived of light soon become blind. An intellectual faculty which is never exerted is soon deprived of the power of exertion.

Modern science is sometimes inclined to boast of its power of controlling nature. But we must never forget that we only control nature through natural laws and cannot infringe them in the smallest degree without suffering the penalties which nature imposes. The laws of art, like most others that regulate human affairs, are founded upon nature’s law.

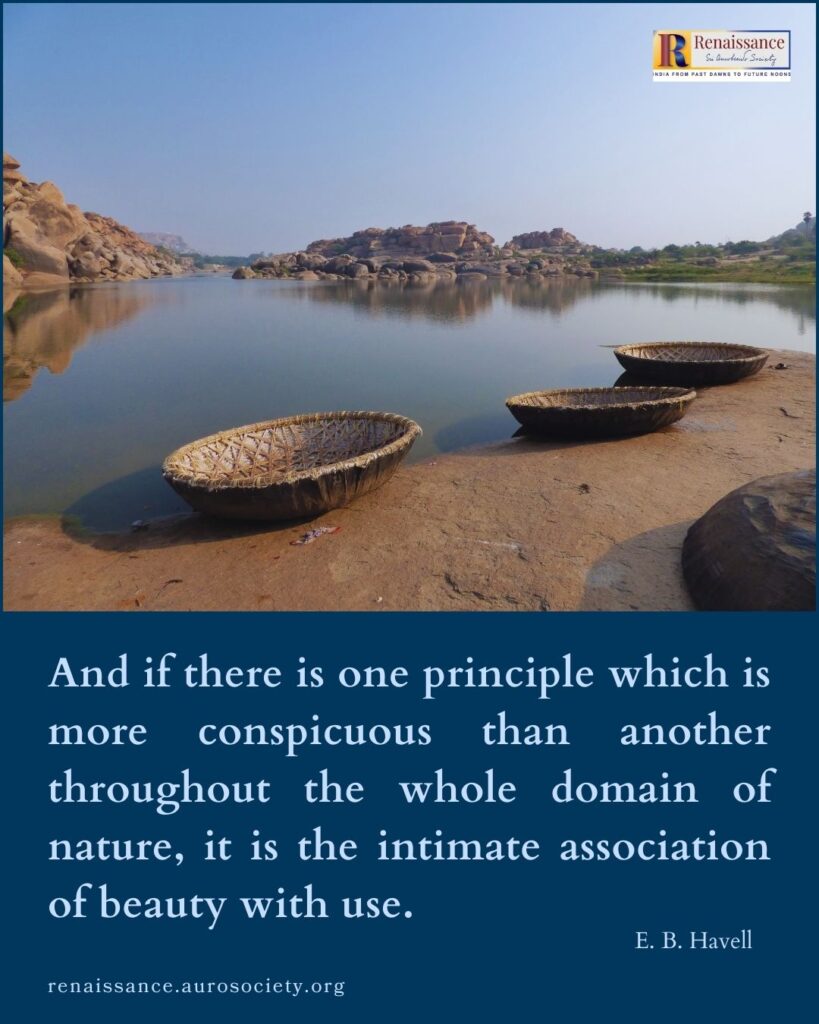

In considering, therefore, the proper relation of art to the necessities of human life it is better to go straight to nature and study the principles we find there, rather than to rely only upon the precedents of history. And if there is one principle which is more conspicuous than another throughout the whole domain of nature, it is the intimate association of beauty with use.

Art as a Form of Worship

The desire for beauty shows itself in the whole order of the universe, from the tiniest atom in the earth under our feet, to the magnificent phenomena of the sky and atmosphere above and around us. Man as the highest product of creation, asserts the right of considering himself at once the most beautiful and the most useful. And I am not going to say anything in dispute of that claim.

But you will find the same principle manifesting itself in endless variations in the beasts, birds, fishes and insects and in every living thing; in every leaf and flower that grows, and further down in the scale in metals, rock and stones, and even in things animate and inanimate too minute for the unaided eye to see.

And, as you examine this universal principle more closely you will never find that the beauty is something apart from usefulness, a thing which can be subtracted or left out. In nature beauty and usefulness are inseparable. It is only in man’s crude and imperfect work that usefulness is so often associated with ugliness.

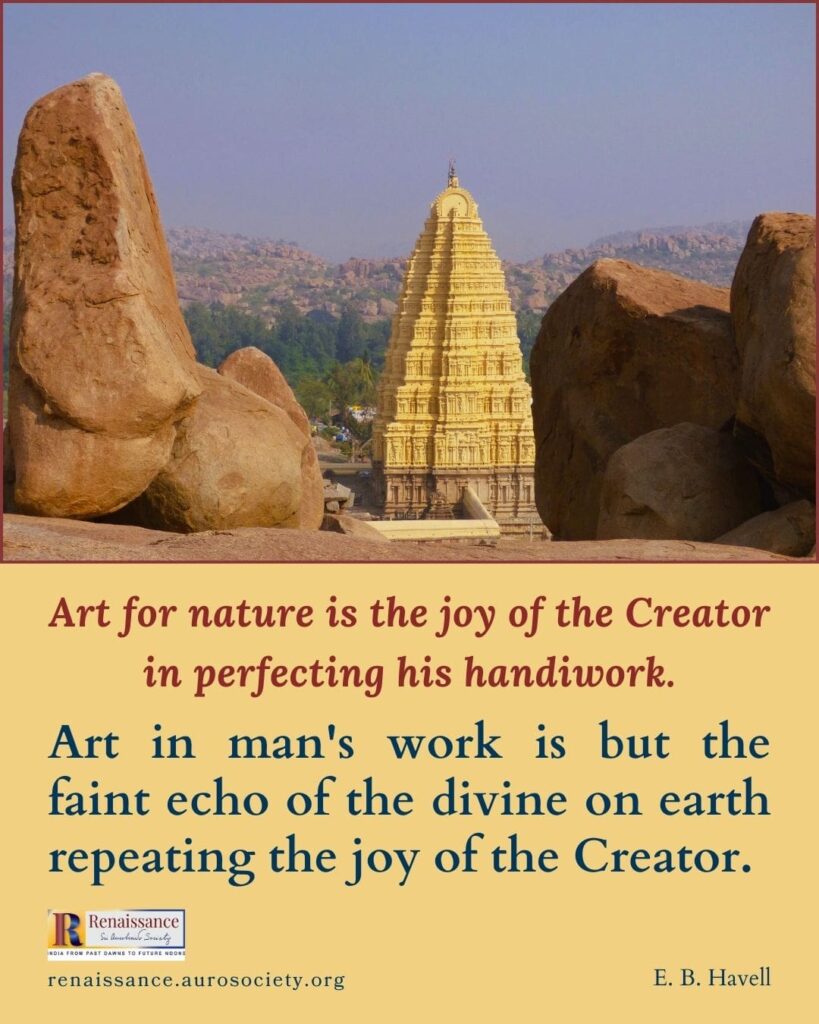

Art for nature is the joy of the Creator in perfecting his handiwork.

Art in man’s work is but the faint echo of the divine on earth repeating the joy of the Creator. Art, then, is in a special sense a form of worship. And you will observe that the finest art in all countries has nearly always been produced in the service of religion.

The Motive for Seeking Beauty

But whether the art was applied to religious purposes, to works of public utility or to common domestic needs, you will find one spirit in all good art in all countries and in all epochs. It is the same spirit as you see in nature’s work — the striving to make the work fit for the purpose for which it was intended. Art, in the abstract, thus becomes the striving to do things well. There is no question of separating utility and beauty. The joy of perfecting the use, consciously or unconsciously, creates the beauty.

Some will perhaps argue that the ugliness generally conspicuous in modern engineering works, railways, bridges, motor-cars and other things undeniably useful, is a proof that use and beauty are often incompatible. But I maintain that the ugliness of these things is not a necessity, but only conclusive evidence of their imperfection.

Also read:

The Obscene and the Ugly

You must remember that the application of iron to building purposes and its use in relation to steam and electric power are but things of yesterday. The beautiful forms which art has created in olden times from the use of brick, stone, wood, and other materials were slowly evolved in thousands of years by the experience and practice of hundreds of generations of craftsmen.

There is every reason, therefore, to believe that as our engineers gain more experience and skill in the use of new materials and in the manifold applications of the new forces now brought into the service of mankind, they will gradually produce more and more beautiful forms; and learn the lesson which nature teaches — perfect fitness is perfect beauty. In fact, the finest works of modern engineering are by no means without a beauty of their own.

But you may ask, is there no art for art’s sake, beauty for beauty’s sake? Yes, surely there is, just as there is mind and body, spirit and matter. Yet, as Emerson says, as soon as beauty is sought after, not for religion and love, but for pleasure, it degrades the seeker. The motive of the artist is writ large in every work of his hand and brain. If the motive is base, the art will be tainted with that baseness.

READ:

Art for Art’s Sake?

The General Inferiority of Modern Art

Why is it that so much of our modern painting and sculpture is small and petty compared with even the average productions of ancient Greece, the works of medieval time, or of the sixteenth century? It is because the artists of the past employed their genius in the service of religion and of the state. They worked for God and for humanity.

Our modern art is mostly for private vanity and amusement. Pictures and statues are goods and chattels to be bought and sold. The man in the street thinks he is entitled to get the art he wants merely because he pays for it. And the artist is more often anxious to gratify the man who pays than to consider what he owes to art and to himself.

No longer intimately associated with the service of church and state, art has become a society toy and a mere item of merchandise in the catalogues of modern commerce. The common trade expressions of art-furniture, art-wood-work, art-metal-work, reflect the popular sentiment towards all art. Plain, ordinary furniture and metal-work, such as an honest workman will produce without any pretence at being artistic, are believed to be necessarily ugly. If you want to be fashionably artistic yon must pay something extra and call in the artist, who will make your things beautiful, but you must be prepared to sacrifice something of utility.

The Narrow Utilitarianism and Commercialism

In former days in Europe trade was to a very large extent controlled by artists, through the great art guilds. And the craftsman and the artist were one and the same person. Or at least the artist was always one who had served a thorough apprenticeship in his craft — just as your Indian artists generally are even in the present day.

Leonardo da Vinci, one of the greatest artists Europe ever produced, was the greatest engineer of his time. Raphael and Michelangelo, and many of the great masters of the Renaissance, designed the buildings for which their paintings and sculpture were intended. And the men who built them were only inferior artists to themselves.

In modern European buildings the architect is often only a draftsman who for want of architectural knowledge imitates the reflection of some ancient buildings intended for totally different purposes. The builder is a contractor who employs men to copy mechanically the architect’s archaeological essays. His first aim is to make as much profit as he can. And his art consists in putting bad ornament to conceal the faults of the design and construction.

The general inferiority of modern art thus merely reflects the narrowness of the utilitarianism and commercialism of the present age. Art, in all countries, always reflects the varying phases of national sentiment. You may trace a nation’s intellectual and moral progress, or decay, much more clearly and convincingly through its art than through its written history. For art is a record which seldom lies.

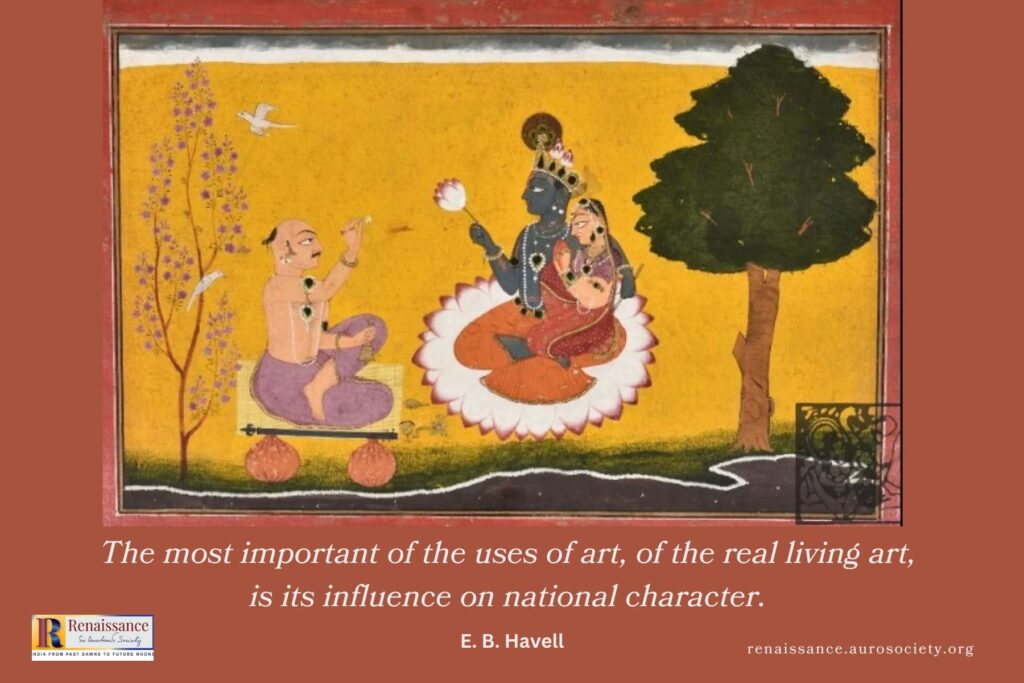

Influence of Art on National Character

A vigorous and healthy national art connotes a vigorous and healthy nation. The nations with the greatest art have always been the leaders in the world’s progress. Japan, which has suddenly sprung to the front rank of nations, is most artistic nation of the present day. […]

The vitalising influence in true national culture is the artistic sense. And there must be something fundamentally unsound in the University system

which leads the educated classes to prefer tawdry commercialism, which generally represents European art in India, to the real art of their own country. And instead of broadening the basis of culture it drives the artists of the country to seek employment in office clerkships.

A system of education which excludes both art and religion can never succeed because it shuts out the two great influences which mould the national character. There are obvious difficulties in a state-aided university identifying itself with religious teaching. But art is neutral ground upon which all creeds and schools of thought can meet. Until educationists in India recognise that the artistic sense is as necessary in the training of men of letters, of scientists, and of engineers, as it is in that of artists, no reforms in mere methods of teaching or examination systems will place higher education on the right road. […]

The most important of the uses of art, of the real living art, is its influence on national character.

You will see it in the character of that great nation, the Japanese. What do you think inspired the magnanimity, humanity, devotion and self-control which they have shown in this great crisis of their history, but the innate and supreme artistic sense of the people? I will give you an instance of the same true artistic spirit which may be found also in India at the present day.

Not so far from Calcutta, at Jajpur, the ancient capital of Orissa, the splendid art of stone-carving which flourished there in former days still lingers in obscurity. For the last 20 or 30 years a few of your real Indian artists have been devotedly working on a pittance of four annas a day carving decoration, more beautiful than any to be found in this city of palaces, for the temple of Biroja in that town. Their wages are paid by a sadhu, a religious mendicant, who has spent his whole life in begging for funds for this purpose. That is the spirit in which all true art is produced.

It is the spirit with which the glorious Gothic cathedrals of medieval Europe were built. It is the moving spirit in everything great and noble that ever art creates. Let such devotion, reverence and Joy permeate your Universities, your public and private life and everything which you undertake. You need not then clamour for political privileges, for there is no power on earth that could deny you them.

Make Art a Part of Your Daily Lives

If you would see that true artistic spirit once more grow and spread, art must be ever present in your daily lives. The art you merely imitate cannot give it to you. It must come out from yourselves. It must not be only a thing you go to see in art galleries and museums. It must be something for daily use — something you see in the life which is round about you, in the streets and in your houses, in the trees and in the flowers, in the fields and in the sky — and something of the divine nature that is within you revealing to you thoughts divine.

You must regard the books which you read only as commentaries on the great book of nature. You must go, as your Rishis did of old, and learn from nature herself. Nature will teach you many things which are not to be found in text-books nor within the dingy walls of your college class-rooms.

Indian art will then again become a great intellectual and moral force which will stimulate every form of activity. It will relight the lamp of Indian learning, revive your architecture, your industries and your commerce, and give a higher motive for every work you find to do. Your art, thus ennobled, will not fail to ennoble yourselves.

About the author:

E.B. Havell was an influential English art historian and author of numerous books on Indian art and architecture. He was the principal of the Government School of Art, Calcutta from 1896 to 1905. There, along with Abanindranath Tagore, he developed a style of art and art education based on Indian ethos and models. This led to the foundation of the Bengal school of art.

~ Design: Beloo Mehra