Volume V, Issue 10

Author: Narendra Murty

Editor’s Note: The author summarizes the essential element of what distinguishes the highest Indian art from that of the West. It is the artist’s insistence on expressing the Infinite in a finite form. To quote from Sri Aurobindo, it is to “disclose something of the Self, the Infinite, the Divine to the regard of the soul, the Self through its expressions, the Infinite through its living finite symbols, the Divine through his powers” (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 267)

The sense of the sacred is native to the Indian mind. The thirst for a higher light was ingrained in the very nerves and sinews of this nation. However, this does not mean that India debased material existence and chose Heaven above Earth. That’s a simplistic and wrong conclusion drawn by hasty Western commentators. Rather the Indian mind sought to bring down Heaven to Earth; or more precisely, through the forms of the Earth, attempted to reach out to Heaven. This is what the Indian mind truly is.

Notwithstanding Buddha and Shankaracharya with their world-negating philosophies – Buddha with his proclamation that samsara is dukkha and Shankaracharya’s radical statement that jagat is mithya or maya. In fact, their own personal lives were not a negation or rejection of the world; but rather demonstrate a compassionate embrace of the world. Whatever their philosophy, both of them were exemplary karmayogis. Acting out of compassion, they worked tirelessly to bring light to the ignorant masses. That is not the way of a man who rejects the world.

While standing on terra firma, Indian civilization has always looked up to a higher reality. The essential aspiration of the Indian mind was to look up. And this has been reflected in all its passions and strivings. This is what separates us from all the other races of the world, reminds Swami Vivekananda.

Let the Persian or the Greek, the Roman, the Arab, or the Englishman march his battalions, conquer the world, and link the different nations together, and the philosophy and spirituality of India is ever ready to flow along the new-made channels into the veins of the nations of the world. The Hindu’s calm brain must pour out its own quota to give to the sum total of human progress. India’s gift to the world is the light spiritual.

~ Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Vol. 3, p. 109

This deep aspiration, this gift of India’s light spiritual to the world is also what we find in its Art. If we leave aside the artefacts of the Indus-Saraswati valley civilizations, then the extant specimens of Indian Art can be traced back to at least 2000 years. And most of the art that survives is sacred in character. It stands to reason that there must have been some kind of secular art as well – buildings, palaces, forts, statues of the kings, mausoleums or whatever, but they do not survive. Such specimens survive only from the Medieval period – in Delhi, Fatehpur Sikri, Lucknow, in the Deccan etc.

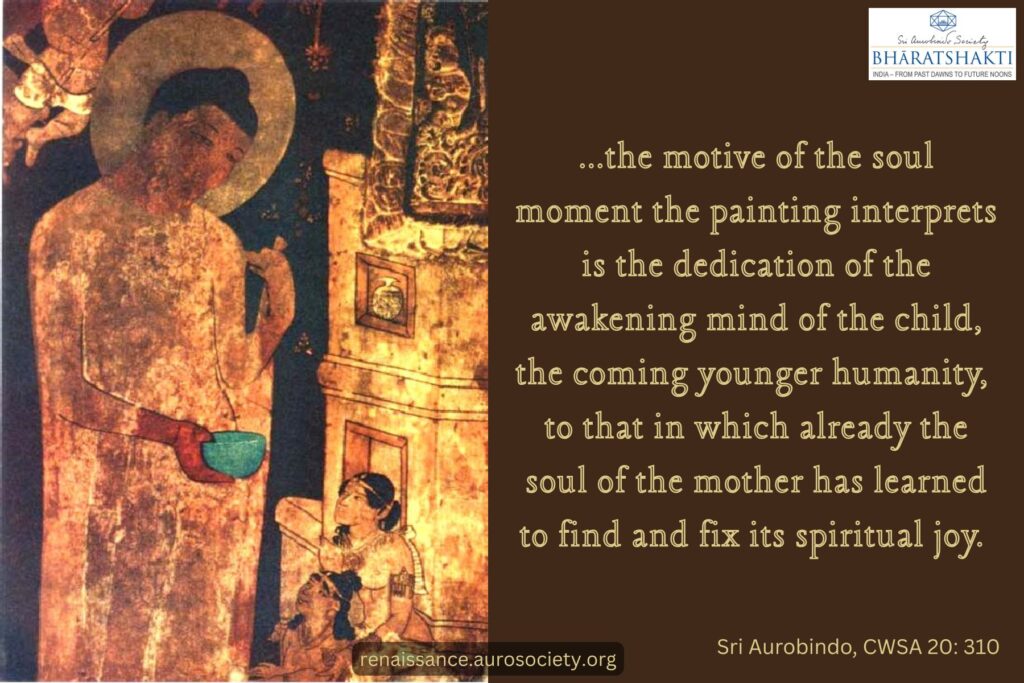

But going back in time, all we find are the cave temples, chaityas and viharas, exquisite figures of gods, humans and animals cut out of rock. Whatever paintings and murals survive – as in Ajanta or in the Tabo monastery in the Spiti valley of Himachal Pradesh (also known as the Ajanta of the Himalayas) – are about the sacred and the divine. By a strange parallelism, art relating to the ephemeral things of the world faded out of existence; and those belonging to the eternal dimension, survived.

The whole basis of Indian artistic creation, perfectly conscious and recognised in the canons, is directly spiritual and intuitive.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 257

Form in Indian Art always pointed to something beyond it. It pointed to a higher dimension beyond the physical. And this happens to be the essential difference between Indian and Western Art, says Sri Aurobindo.

The Western mind, which is more generally captivated by the form, fails to appreciate Indian Art because it is stuck in the physical and vital. Since it is not in sympathy with that unseen, higher dimension, it is unable to comprehend Indian Art. Western Art, for the most part, does not go beyond the physical. This is not to say that Western Art is not beautiful. The question is not about beauty; the issue here is dimension. There are wonderful, breathtaking specimens of beauty in Western Art, but they belong to the terrestrial dimension. Sri Aurobindo tells us:

Here [in the Indian art] it is the spirit that carries the form, while in most Western art it is the form that carries whatever there may be of spirit…The more ordinary Western outlook is upon animate matter carrying in its life a modicum of soul. But the seeing of the Indian mind and of Indian art is that of a great, a limitless self and spirit, mahān ātmā….

~ CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 271

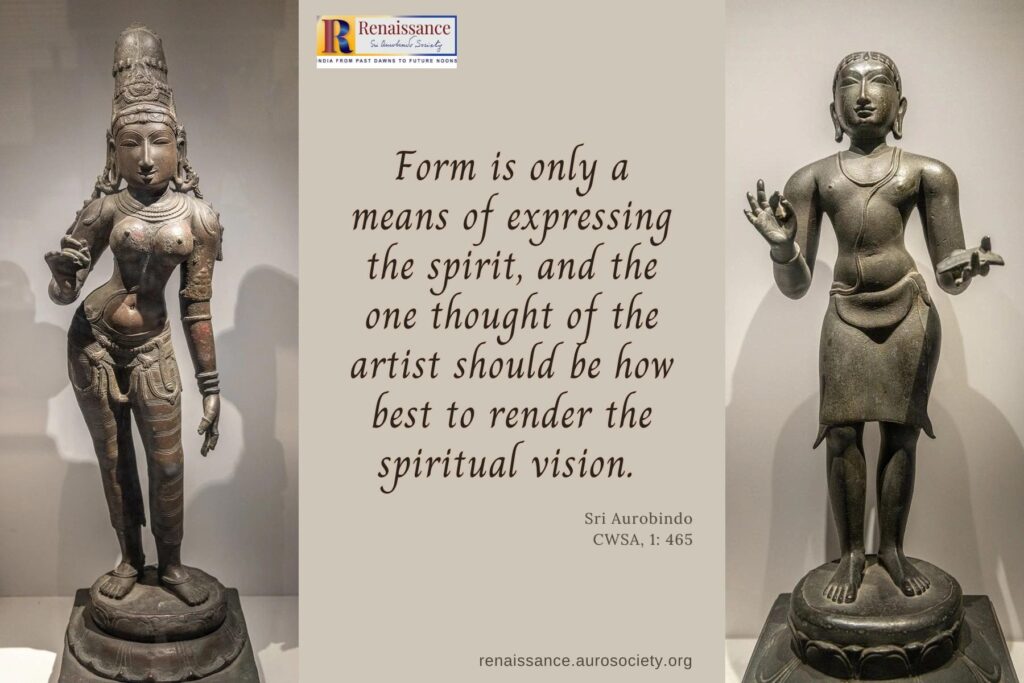

To illustrate this point, I pick two famous sculptures — one from the Western and one from the Indian tradition. While the two belong to different time periods, both are considered quite iconic as illustrative of some of the best art created in Europe and India.

There is no denying the fact that Michelangelo’s Pietà is a magnificent piece of art in terms of artistry and skill of execution. But it is human, at least to this author it feels that way. Jesus laying in final rest on his mother’s lap depicts more of a human tragedy rather than something about the Avatar who is the Son of God. It evokes the element of pathos or karuna rasa, the term used in Indian aesthetics. But again, though beautiful and soulful, it still remains in the earthly and human dimension.

On the other hand, the Trimurti of Elephanta brings to mind something not belonging to this world. The ethereal form depicting the creator, preserver and destroyer in one image takes the observer instantly to the transcendental plane. It has no resemblance to anything of this world.

We may say that the essential spirit behind Indian Art has not been about imitating life; it is rather about envisioning and expressing the Divine — the Divine in life, the Infinity of the Divine in a finite form. We see this reflected in the Elephanta Trimurti. We see this also in the supremely serene face of Padmapani at Ajanta reflecting the glow of Nirvana.

The beauty and serenity of Padmapani is celestial and trans-human. It at once points to the transcendental dimension – the bliss and beatific radiance emanating from the state of Nirvana. It compels you to go beyond the form because the artist’s intention has been to express the truth of the spirit through the form. This amply demonstrates the truth of Sri Aurobindo’s assertion when he writes:

The Western mind is arrested and attracted by the form, lingers on it and cannot get away from its charm, loves it for its own beauty, rests on the emotional, intellectual, aesthetic suggestions that arise directly from its most visible language, confines the soul in the body… The Indian attitude to the matter is at the opposite pole to this view. For the Indian mind form does not exist except as a creation of the spirit and draws all its meaning and value from the spirit.

~ CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 270

Also read:

The Spiritual Roots of Art in India

The highest and best art in ancient India was conceived and executed with always the sacred and the divine as its base and as well as its pinnacle. Today whatever secular art we find in India whether in the form of Taj Mahal, Red Fort, Imambara of Lucknow, Fatehpur Sikri or in the magnificent forts spread all over India from Rajasthan to the Deccan – they all belong to Medieval India which emerged only after the Islamic conquest of this land.

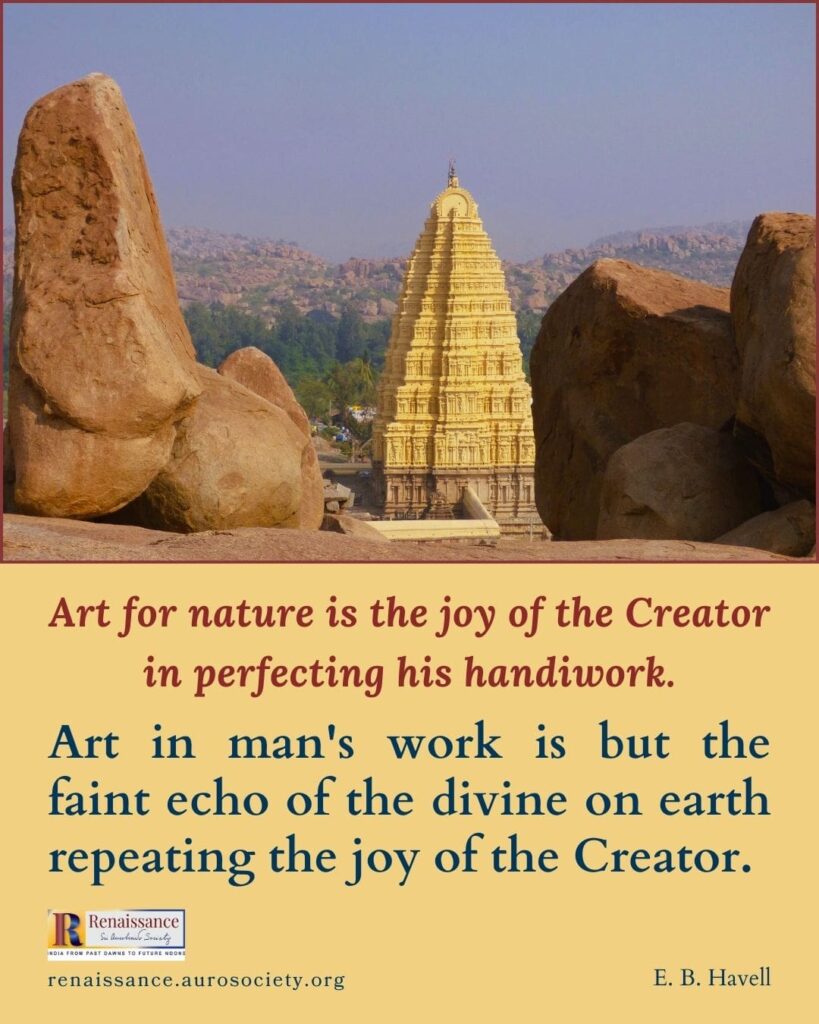

In contrast, the highest art in ancient India was always rooted in the Divine. Even after the Gupta period, it continued to find new and ever new expressions – in the Chola bronzes depicting Nataraja, the Cosmic Dancer; in the vivid imagery of Tantric Art which contained even erotic themes and in the breathtaking temple architecture of Medieval India. At places such as Belur, Halebidu, Hampi, Khajuraho, Konark, Mahabalipuram, we find some of the finest monuments of sacred Indian art.

Read:

Art in India: A Quick Historical Look – I

The influence of sacred Indian art spread beyond the eastern borders of this land and we find awe-inspiring examples of it in the Angkor Wat of Cambodia (declared the largest religious structure in the world) and in the Borobudur of Indonesia. This dominant and underlying note of supra-physical and super-sensuous vision of Indian Art has been powerfully expressed by Sri Aurobindo in these lines in Savitri:

Overpassing lines that please the outward eyes

~ CWSA, Vol. 34, p. 360

But hide the sight of that which lives within

Sculpture and painting concentrated sense

Upon an inner vision’s motionless verge,

Revealed a figure of the invisible,

Unveiled all Nature’s meaning in a form,

Or caught into a body the Divine.

What was expressed in sculpture and painting in the highest art of ancient India was an inner vision of a supra-physical beauty. These were glimpses of the Divine caught in a state of inner absorption and meditation, and thereafter captured on the physical plane – in stone and in colours. In the body. In the temples of Brihadeshwar in Thanjavur, Kailash of Ellora, Kandariya Mahadev in Khajuraho or the sun temples of Modhera and Konark.

The architecture of the Infinite

~ CWSA, Vol. 34, pp. 360-361

Discovered here its inward-musing shapes

Captured into wide breadths of soaring stone:

~ Design: Beloo Mehra