Volume V, Issue 11-12

Author: The Mother

CONTINUED FROM PART I

Editor’s Note: In Part 2, the Mother explains the phenomenon of mushroom art where art becomes disconnected with life and is no longer an expression of integral harmony and beauty. For easier online reading, we have made a few formatting revisions with no change in the text.

Disciple’s Question

Have Yogis done greater dramas than Shakespeare?

The Mother’s Response

Drama is not the highest of the arts. Someone has said that drama is greater than any other art and art is greater than life. But it is not quite like that.

The mistake of the artist is to believe that artistic production is something that stands by itself and for itself, independent of the rest of the world. Art as understood by these artists is like a mushroom on the wide soil of life, something casual and external, not something intimate to life; it does not reach and touch the deep and abiding realities, it does not become an intrinsic and inseparable part of existence.

True art is intended to express the beautiful, but in close intimacy with the universal movement.

The greatest nations and the most cultured races have always considered art as a part of life and made it subservient to life. Art was like that in Japan in its best moments; it was like that in all the best moments in the history of art.

But most artists are like parasites growing on the margin of life; they do not seem to know that art should be the expression of the Divine in life and through life. In everything, everywhere, in all relations truth must be brought out in its all-embracing rhythm and every movement of life should be an expression of beauty and harmony. Skill is not art, talent is not art. Art is a living harmony and beauty that must be expressed in all the movements of existence. This manifestation of beauty and harmony is part of the Divine realisation upon earth, perhaps even its greatest part.

For, from the supramental point of view beauty and harmony are as important as any other expression of the Divine. But they should not be isolated, set up apart from all other relations, taken out from the ensemble; they should be one with the expression of life as a whole.

People have the habit of saying, “Oh, it is an artist!” as if an artist should not be a man among other men but must be an extraordinary being belonging to a class by itself, and his art too something extraordinary and apart, not to be confused with the other ordinary things of the world. The maxim, “Art for art’s sake”, tries to impress and emphasise as a truth the same error. It is the same mistake as when men place in the middle of their drawing-rooms a framed picture that has nothing to do either with the furniture or the walls, but is put there only because it is an “object of art”.

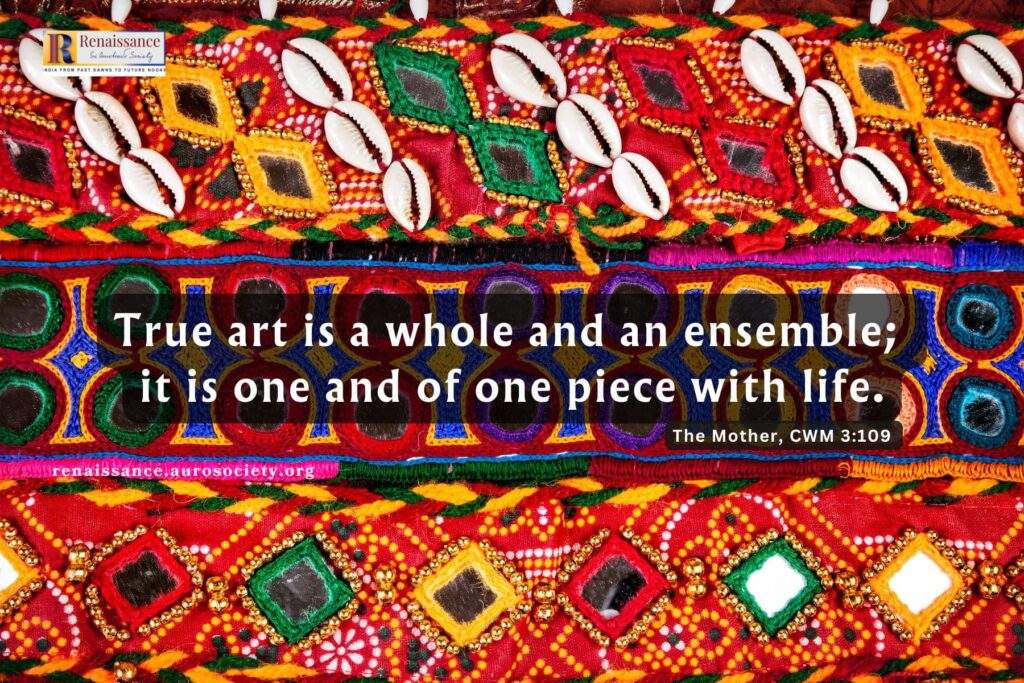

True art is a whole and an ensemble; it is one and of one piece with life.

You see something of this intimate wholeness in ancient Greece and ancient Egypt; for there pictures and statues and all objects of art were made and arranged as part of the architectural plan of a building, each detail a portion of the whole.

It is like that in Japan, or at least it was so till the other day before the invasion of a utilitarian and practical modernism. A Japanese house is a wonderful artistic whole; always the right thing is there in the right place, nothing wrongly set, nothing too much, nothing too little. Everything is just as it needed to be, and the house itself blends marvellously with the surrounding nature.

In India, too, painting and sculpture and architecture were one integral beauty, one single movement of adoration of the Divine.

There has been in this sense a great degeneration since then in the world. From the time of Victoria and in France from the Second Empire we have entered into a period of decadence. The habit has grown of hanging up in rooms pictures that have no meaning for the surrounding objects; any picture, any artistic object could now be put anywhere and it would make small difference. Art now is meant to show skill and cleverness and talent, not to embody some integral expression of harmony and beauty in a home.

But latterly there has come about a revolt against this lapse into bourgeois taste. The reaction was so violent that it looked like a complete aberration and art seemed about to sink down into the absurd. Slowly, however, out of the chaos something has emerged, something more rational, more logical, more coherent to which can once more be given the name of art, an art renovated and perhaps, or let us hope so, regenerated.

Art is nothing less in its fundamental truth than the aspect of beauty of the Divine manifestation.

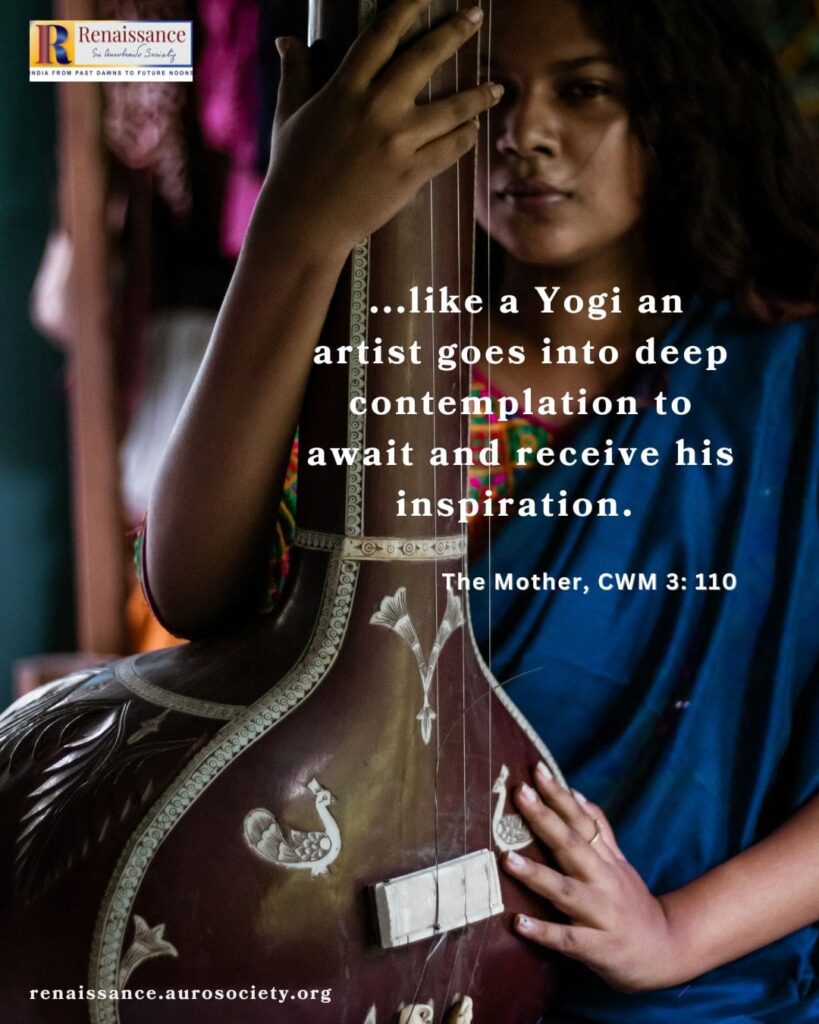

Perhaps, looking from this standpoint, there will be found very few true artists; but still there are some and these can very well be considered as Yogis. For like a Yogi an artist goes into deep contemplation to await and receive his inspiration.

To create something truly beautiful, he has first to see it within, to realise it as a whole in his inner consciousness; only when so found, seen, held within, can he execute it outwardly; he creates according to this greater inner vision. This too is a kind of yogic discipline, for by it he enters into intimate communion with the inner worlds. A man like Leonardo da Vinci was a Yogi and nothing else. And he was, if not the greatest, at least one of the greatest painters,—although his art did not stop at painting alone.

Music too is an essentially spiritual art and has always been associated with religious feeling and an inner life. But, here too, we have turned it into something independent and self-sufficient, a mushroom art, such as is operatic music. Most of the artistic productions we come across are of this kind and at best interesting from the point of view of technique.

I do not say that even operatic music cannot be used as a medium of a higher art expression; for whatever the form, it can be made to serve a deeper purpose. All depends on the thing itself, on how it is used, on what is behind it. There is nothing that cannot be used for the Divine purpose—just as anything can pretend to be the Divine and yet be of the mushroom species.

Among the great modern musicians there have been several whose consciousness, when they created, came into touch with a higher consciousness. César Franck played on the organ as one inspired; he had an opening into the psychic life and he was conscious of it and to a great extent expressed it. Beethoven, when he composed the Ninth Symphony, had the vision of an opening into a higher world and of the descent of a higher world into this earthly plane.

Wagner had strong and powerful intimations of the occult world; he had the instinct of occultism and the sense of the occult and through it he received his greatest inspirations. But he worked mainly on the vital level and his mind came in constantly to interfere and mechanised his inspiration. His work for the greater part is too mixed, too often obscure and heavy, although powerful. But when he could cross the vital and the mental levels and reach a higher world, some of the glimpses he had were of an exceptional beauty, as in Parsifal, in some parts of Tristan and Iseult and most in its last great Act.

Look again at what the moderns have made of the dance; compare it with what the dance once was. The dance was once one of the highest expressions of the inner life; it was associated with religion and it was an important limb in sacred ceremony, in the celebration of festivals, in the adoration of the Divine. In some countries it reached a very high degree of beauty and an extraordinary perfection.

In Japan they kept up the tradition of the dance as a part of the religious life and, because the strict sense of beauty and art is a natural possession of the Japanese, they did not allow it to degenerate into something of lesser significance and smaller purpose. It was the same in India. It is true that in our days there have been attempts to resuscitate the ancient Greek and other dances; but the religious sense is missing in all such resurrections and they look more like rhythmic gymnastics than dance. […]

READ:

The Rapture of the Cosmic Dance

There is a domain far above the mind which we could call the world of Harmony and, if you can reach there, you will find the root of all harmony that has been manifested in whatever form upon earth.

For instance, there is a certain line of music, consisting of a few supreme notes, that was behind the productions of two artists who came one after another—one a concerto of Bach, another a concerto of Beethoven. The two are not alike on paper and differ to the outward ear, but in their essence they are the same. One and the same vibration of consciousness, one wave of significant harmony touched both these artists. Beethoven caught a larger part, but in him it was more mixed with the inventions and interpolations of his mind; Bach received less, but what he seized of it was purer. The vibration was that of the victorious emergence of consciousness, consciousness tearing itself out of the womb of unconsciousness in a triumphant uprising and birth.

If by Yoga you are capable of reaching this source of all art, then you are master, if you will, of all the arts.

Those that may have gone there before, found it perhaps happier, more pleasant or full of a rapturous ease to remain and enjoy the Beauty and the Delight that are there, not manifesting it, not embodying it upon earth. But this abstention is not all the truth nor the true truth of Yoga; it is rather a deformation, a diminution of the dynamic freedom of Yoga by the more negative spirit of Sannyasa.

The will of the Divine is to manifest, not to remain altogether withdrawn in inactivity and an absolute silence; if the Divine Consciousness were really an inaction of unmanifesting bliss, there would never have been any creation.

~ The Mother, CWM, Volume 3, pp. 104-113

Read PART I

~ Content Research & Design: Beloo Mehra