Volume VI, Issue 1

Author: Sri Aurobindo

Editor’s Note: We feature in 2 parts selections from Sri Aurobindo’s brilliant essay which describes the deepest inner significance and symbolism of an Indian temple. The focus in this part is on how one must ‘see’ the temple to get closer to the truth it represents in its architectural content.

PART I

A great oriental work of art does not easily reveal its secret to one who comes to it solely in a mood of aesthetic curiosity or with a considering critical objective mind, still less as the cultivated and interested tourist passing among strange and foreign things; but it has to be seen in loneliness, in the solitude of one’s self, in moments when one is capable of long and deep meditation and as little weighted as possible with the conventions of material life…

An Inner Study is Demanded

Indian architecture especially demands this kind of inner study and this spiritual self-identification with its deepest meaning and will not otherwise reveal itself to us.

The secular buildings of ancient India, her palaces and places of assembly and civic edifices have not outlived the ravage of time; what remains to us is mostly something of the great mountain and cave temples, something too of the temples of her ancient cities of the plains, and for the rest we have the fanes and shrines of her later times, whether situated in temple cities and places of pilgrimage like Srirangam and Rameshwaram or in her great once regal towns like Madura, when the temple was the centre of life.

It is then the most hieratic side of a hieratic art that remains to us. These sacred buildings are the signs, the architectural self-expression of an ancient spiritual and religious culture. Ignore the spiritual suggestion, the religious significance, the meaning of the symbols and indications, look only with the rational and secular aesthetic mind, and it is vain to expect that we shall get to any true and discerning appreciation of this art.

And it has to be remembered too that the religious spirit here is something quite different from the sense of European religions; and even mediaeval Christianity, especially as now looked at by the modern European mind which has gone through the two great crises of the Renascence and recent secularism, will not in spite of its oriental origin and affinities be of much real help.

Do Not Compare

To bring in into the artistic look on an Indian temple occidental memories or a comparison with Greek Parthenon or Italian church or Duomo or Campanile or even the great Gothic cathedrals of mediaeval France, though these have in them something much nearer to the Indian mentality, is to intrude a fatally foreign and disturbing element or standard in the mind.

But this consciously or else subconsciously is what almost every European mind does to a greater or less degree,—and it is here a pernicious immixture, for it subjects the work of a vision that saw the immeasurable to the tests of an eye that dwells only on measure.

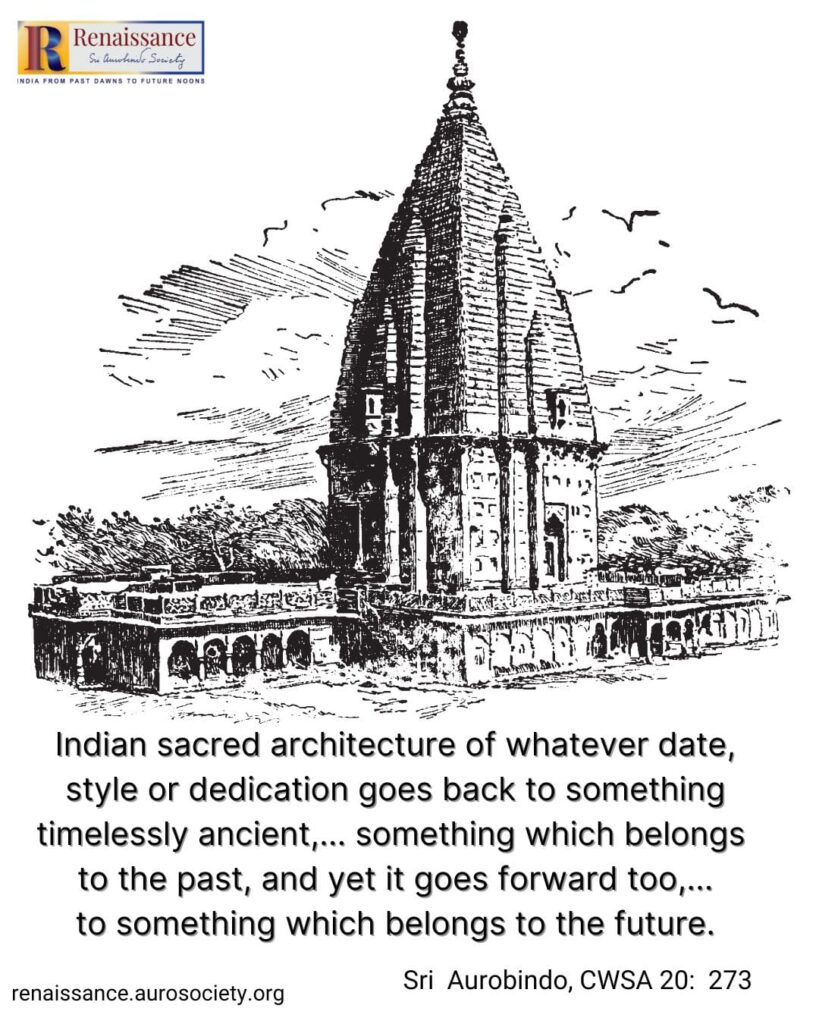

Indian sacred architecture of whatever date, style or dedication goes back to something timelessly ancient and now outside India almost wholly lost, something which belongs to the past, and yet it goes forward too, though this the rationalistic mind will not easily admit, to something which will return upon us and is already beginning to return, something which belongs to the future.

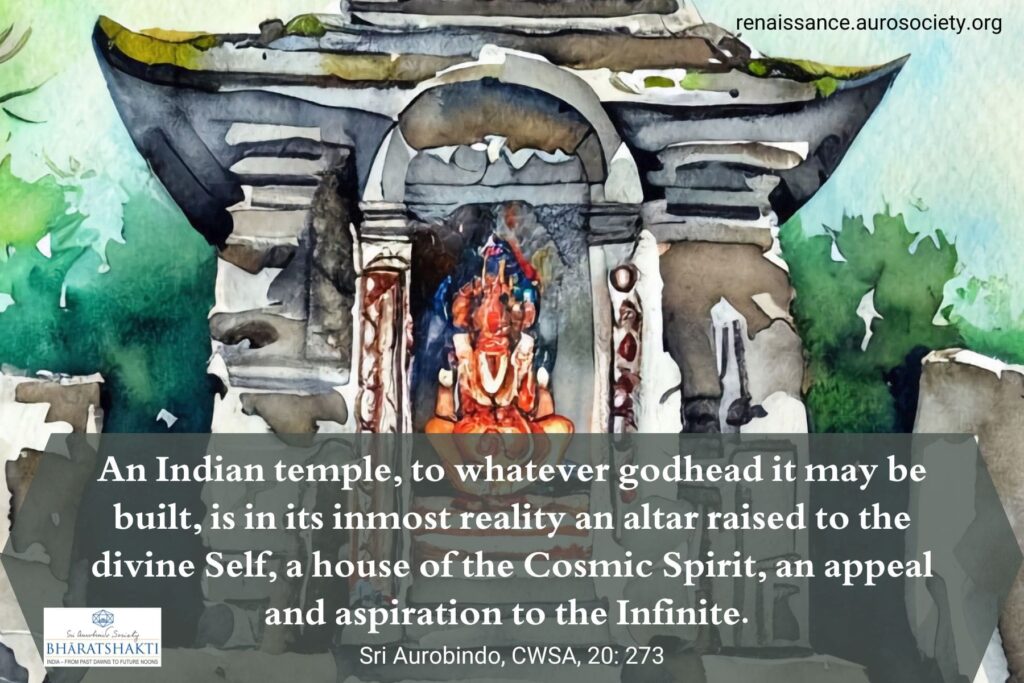

An Indian temple, to whatever godhead it may be built, is in its inmost reality an altar raised to the divine Self, a house of the Cosmic Spirit, an appeal and aspiration to the Infinite. As that and in the light of that seeing and conception it must in the first place be understood, and everything else must be seen in that setting and that light, and then only can there be any real understanding.

Open Your Mind to the Suggestion of the Infinite

No artistic eye however alert and sensible and no aesthetic mind however full and sensitive can arrive at that understanding, if it is attached to a Hellenised conception of rational beauty or shuts itself up in a materialised or intellectual interpretation and fails to open itself to the great things here meant by a kindred close response to some touch of the cosmic consciousness, some revelation of the greater spiritual self, some suggestion of the Infinite.

These things, the spiritual self, the cosmic spirit, the Infinite, are not rational, but suprarational, eternal presences, but to the intellect only words, and visible, sensible, near only to an intuition and revelation in our inmost selves. An art which starts from them as a first conception can only give us what it has to give, their touch, their nearness, their self-disclosure, through some responding intuition and revelation in us, in our own soul, our own self. It is this which one must come to it to find and not demand from it the satisfaction of some quite other seeking or some very different turn of imagination and more limited superficial significance.

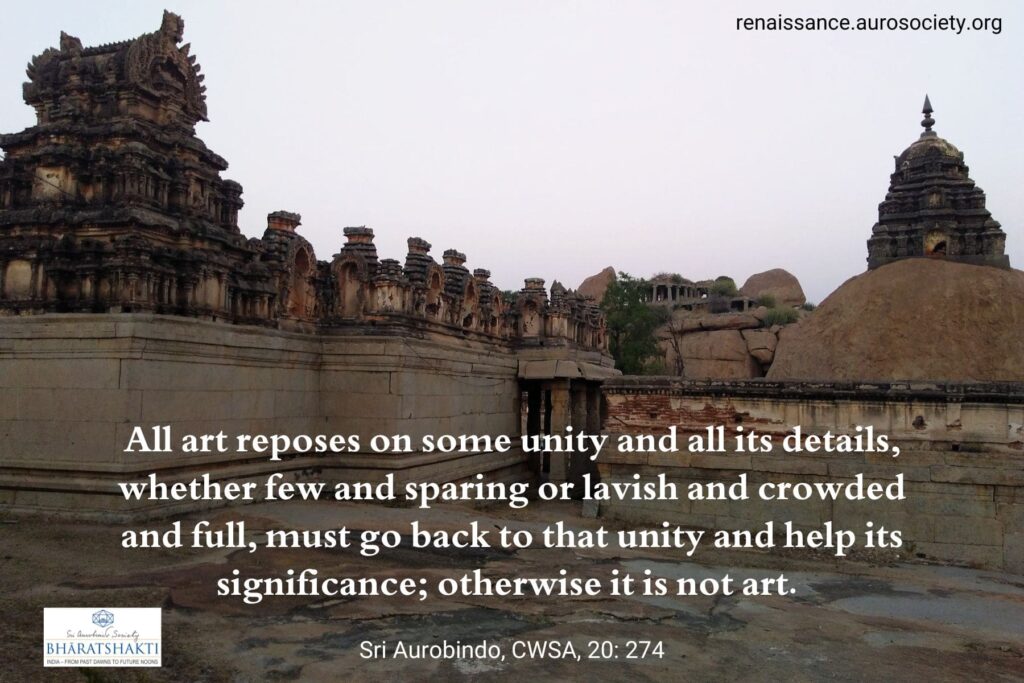

This is the first truth of Indian architecture and its significance which demands emphasis and it leads at once to the answer to certain very common misapprehensions and objections. All art reposes on some unity and all its details, whether few and sparing or lavish and crowded and full, must go back to that unity and help its significance; otherwise it is not art.

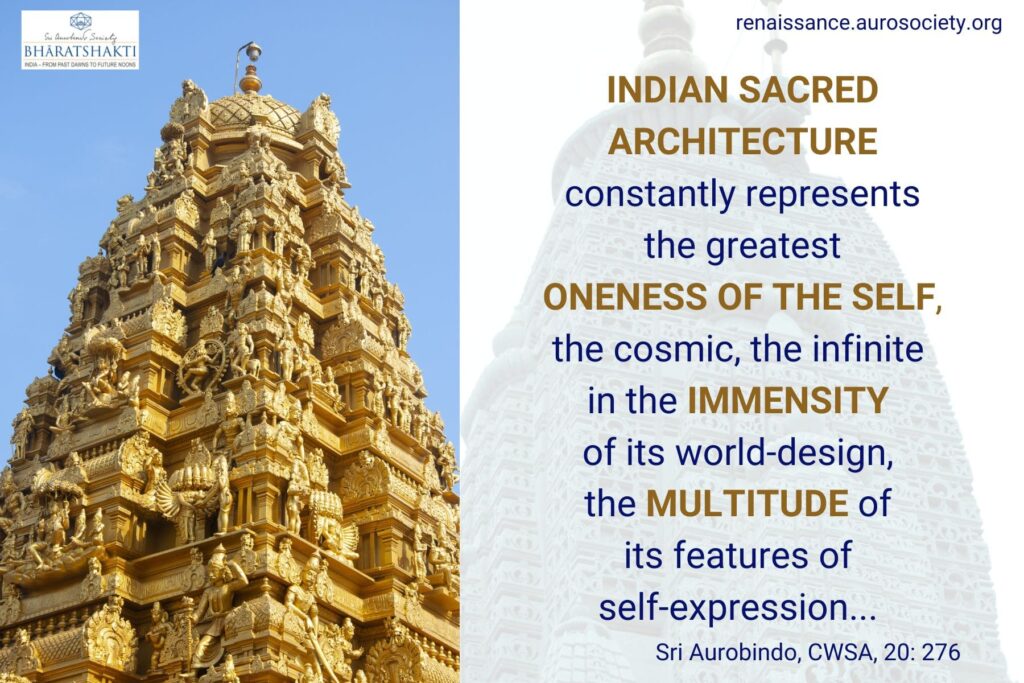

An Indian Temple Represents the Greatest Oneness of the Self

Now we find our Western critic telling us with an assurance which would be stupefying if one did not see how naturally it arose, that in Indian architecture there is no unity, which is as much as to say that there is here no great art at all, but only a skill in the execution of crowded and unrelated details. We are told even by otherwise sympathetic judges that there is an overloading of ornament and detail which, however beautiful or splendid in itself, stands in the way of unity, an attempt to load every rift with ore, an absence of calm, no unfilled spaces, no relief to the eye.[…]

Now it may readily be admitted that the failure to see at once the unity of this architecture is perfectly natural to a European eye, because unity in the sense demanded by the Western conception, the Greek unity gained by much suppression and a sparing use of detail and circumstance or even the Gothic unity got by casting everything into the mould of a single spiritual aspiration, is not there.

Also read by Sri Aurobindo:

The Persistent within the Transient

And the greater unity that really is there can never be arrived at at all, if the eye begins and ends by dwelling on form and detail and ornament, because it will then be obsessed by these things and find it difficult to go beyond to the unity which all this in its totality serves not so much to express in itself, but to fill it with that which comes out of it and relieve its oneness by multitude.

An original oneness, not a combined or synthetic or an effected unity, is that from which this art begins and to which its work when finished returns or rather lives in it as in its self and natural atmosphere.

The Infinite in the Immensity of its World-design

Indian sacred architecture constantly represents the greatest oneness of the self, the cosmic, the infinite in the immensity of its world-design, the multitude of its features of self-expression, lakṣaṇa, (yet the oneness is greater than and independent of their totality and in itself indefinable), and all its starting-point of unity in conception, its mass of design and immensity of material, its crowding abundance of significant ornament and detail and its return towards oneness are only intelligible as necessary circumstances of this poem, this epic or this lyric—for there are smaller structures which are such lyrics—of the Infinite.

The Western mentality, except in those who are coming or returning, since Europe had once something of this cult in her own way, to this vision, may find it difficult to appreciate the truth and meaning of such an art, which tries to figure existence as a whole and not in its pieces; but I would invite those Indian minds who are troubled by these criticisms or partly or temporarily overpowered by the Western way of seeing things, to look at our architecture in the light of this conception and see whether all but minor objections do not vanish as soon as the real meaning makes itself felt and gives body to the first indefinable impression and emotion which we experience before the greater constructions of the Indian builders.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, pp. 271- 276

Continued in Part 2

~ Design: Beloo Mehra