Volume VI, Issue 4

Author: T.A. Gopinatha Rao

Editor’s Note: The sculptural heritage of India is closely linked with the long tradition of image worship. The following excerpt taken from the book titled Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol. 1, Part 1, briefly explores this. First published in 1914 by Motilal Banarsidas Publishers Pvt. Ltd., Delhi, the full set of 4 books (two volumes in two parts each) was reprinted in 1985, 1993 and 1997. The selection featured here is from pages 1-8.

The origin of image worship in India appears to be very ancient and its causes are not exactly known. Many believe it to be the result of the followers of Gautama Buddha adoring their master and worshipping him in the form of images on his apotheosis after death. However, there are indications on the prevalence of image worship among the Hindus long before the time of Gautama Buddha.

The employment of an external object to concentrate the mind upon in the act of meditation in carrying on the practice of Yoga is in India quite as old as Yoga itself. Patañjali defines dhārana or fixity of attention as “the process of fixing the mind on some object well defined in space.” This process is, as he says, “of two kinds, in consequence of this defined space being internal or external. The external object, defined in space consists of the circle of the navel (the nabi-chakra), the heart and so on. The fixing the mind thereon is merely directing in existence to be there.”

There is indeed ample evidence to show that the practice of Yoga is in this country much older that the time of Patañjali. Vāchaspati Miśra, a commentator on Vyāsadēva’s Bhāshya on Patañjali’s Yoga-Sūtras, mentions a great sage Hiranyagarbha as the founder of the Yoga doctrine, which, he adds, was simply improved upon and promulgated by Patañjali, as evidenced by the use of the word anuśāsanam in Patañjali’s first aphorism Atha yōgāanuśāsanam.

This old sage Hiranyāgarbha and his successor Vārshaganya Yājñavalkya are alluded to by Rāmānuja and other later teachers of Vēdānta. And Śankara actually quotes some Yoga aphorisms which are found in the work of Patañjali, but look older than his time. It is, therefore, clear that image worship among the Hindus was cotemporaneous with, if not older than, the development of the Yoga system, which, as we have seen, dates from before the of Patañjali, who has been assigned by scholars on good evidence to the second century before Christ.

There is no doubt that the Yoga system is even older than the time of Buddha. Because Buddha himself is declared to have been initiated into its practice in the earlier stages of his search after enlightenment and truth. And it may be taken that this fact is evidenced by sculptured representations of Buddha in the style of the Gandhara school as an emaciated person almost dying under the stress of the austerities he practised.1

Again, Panini, to whom certain Orientalists assign a date somewhere about the sixth century before Christ, mentions in one of his grammatical aphorisms (v. 3, 99) that “likenesses not to be sold but used for the purpose of livelihood do not take the termination kan.” The word he uses to denote an image in a nearly preceding (v. 6, 96) aphorism is pratikriti, the liberal meaning whereof is anything made after an original. Commentators on this aphorism understand these unsellable reproductions to be divine images.

Evidently then, there were images of gods and goddesses in the days of Panini, which were apparently not sold in the bazaars, but were, nevertheless, used for the purpose of making a living. This would indicate that the possessors of these images were able to utilise them as religious objects which were so sacred as to justify the gift of alms to those who owned and exhibited them. Finally, images of gods, as they laugh, cry, dance, perspire, crack and so forth are mentioned in the Adbhuta-Brāhmaṇa, which is the last of the six chapters of the Ṣaḍviṃśa-Brāhmaṇa, a supplement to the Pañchaviṃśa-Brāhmaṇa”2.

As regards the existence or otherwise of image worship in the Vedic period in the history of India, opinion is divided among European savants. Prof. Max Muller (Chips from a German Workshop, I. 35), answers the question, ‘Did the Vedic Indians make images of their gods’, in the negative. He says, “The religion of the Veda knows no idols. The worship of idols in India is a secondary formation, a later degeneration of the more primitive worship of the ideal gods.”

On the other hand, Dr. Bollenson finds in the hymns clear references to images of the gods (Journ. of the Germ. Orient. Soc. xxii, 587, ff). “From the common appellation of the gods as divo naras, ‘men of the sky’ or simply naras (later?), ‘men’ and from the epithet nripesas, ‘having the form of men’ (R.V. iii, 4, 5) we may conclude that the Indians did not merely in imagination assign human forms to their gods, but also represented them in a sensible manner.”

Image worship seems to have become common in the time of Yāska. In his Nirukta he says, “We are now to consider the forms of the gods. One mode of representation in the hymn makes them resemble men; for, they are praised and addressed as intelligent beings. They are also celebrated with limbs such as those of men.”

Later on Patañjali even gives in a casual manner an idea as to the images which were then commonly in use: he says in the Mahābhāshya, “What about such likenesses as of Śiva, Skanda and Viśākha, which are known as Śiva, Skanda and Viśākha, and not Śivaka, Skandaka, or Viśākhaka?” In the Ramayana, we see mention of temples in Lanka (Bk. VI. 39, 21), clearly evidencing the fact that there existed at least in South India the worship of images enshrined in temples.

Thus there appears to be evidence enough to suggest that image worship was probably not unknown even to the Vedic Indian; and it seems likely that he was at least occasionally worshipping his gods in the form of images, and continued to do so afterwards also. Such is the evidence as to image worship to be found in early Sanskrit Literature. It is desirable to direct our attention to actual sculptures and to references to images occurring in ancient inscriptions.

The oldest piece of sculpture, in South India distinctly Hindu in character, is as far as it is known now, the Linga at Gudimallam. From the features of the figure of Śiva carved thereon in half relief, from the ornaments worked out on the figure, from the arrangement of the drapery, from the battle-axe upon the shoulder, and many other characteristics, it may be put down to belong to the period of Bhaurhat sculptures, that is to the second century before Christ. This remarkable piece of sculpture is interesting in two ways; it at once assures us of the exact nature of early Linga worship and also affords us a lower limit of time in relation to the worship of Śiva in the form of a Linga. From this Linga we may safely conclude that Linga worship is at least as old as the 2nd century B.C.

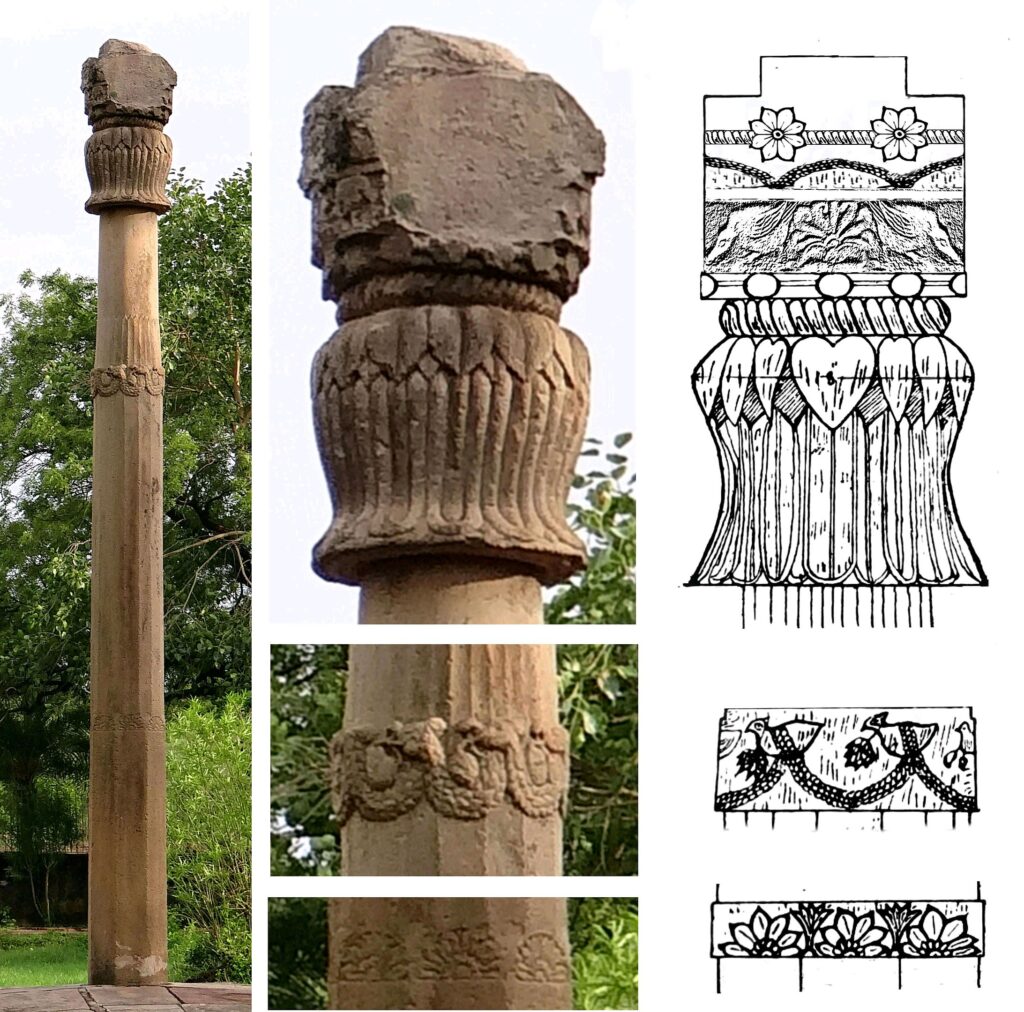

Then again, the inscription on a Garudastambha discovered in Besnagar [Vidisha] quite recently, states that Heliodoros, the son of Dion, a Bhāgavata, who came from Taxila in the reign of the great king Antalkidas set up that Garuda-dhvaja in honour of Vāsudeva. For this king Antalkidas various initial dates have been fixed, which range from B.C. 175 to 135. This is about the earliest known inscription mentioning Vishnu as Vāsudeva; and from this we are in a position to assert that the worship of Vāsudeva in temples in India cannot be later than the 2nd century B.C.

The following are some of the noteworthy references to the iconographic aspect of the Vishnu cult in inscriptions. The Udayagiri Cave inscription of …dhala, son of Vishnudāsa, grandson of Chhagala and vassal of the Gupta king, Chandragupta II, dated the Gupta Era 82 (A.D. 401-2), records the dedication of a rock-cut shrine to Vishnu. The updated inscription of the Bhitāri stone pillar, belonging to the reign of Skandagupta, mentions that an image of the god Sārngin was set up and a village was allotted for its worship. Certain repairs to the lake Sudarśana by the governor Parnadatta’s agent Chakrapālita is said to have been made in the Gupta year 138 (A.D.457-8). The same person also built a temple to Chakrabhrit (Vishnu).

The Gandhar inscription of Viśvakarma, dated A.D. 423-4, records that a person built a temple for Vishnu and the Sapta-Mātrikās and dug a well for drinking water. Iran stone pillar inscription of the time of Budhagupta, dated Gupta Era 165 (A.D. 484-5), informs us that a Mahārāja Mātarivishnu and his younger brother Dhanyavishnu erected a dhvaja-stambha for the god Janārddana. The Khoh copper-plates of Mahārāja Samkshobha dated G.E. 209 (A.D. 528-9), begins with the famous ‘twelve-lettered mantra’, Om Namo Bhagavate Vasudevaya of the Bhāgavatas.

The following are similar references to the Śiva cult in inscriptions. Udayagiri Cave inscription of the reign of Chandragupta II, records the excavation of a shrine for Śambu; while another in Bilsad, belonging to the reign of Kumaragupta, and dated G.E. 96 (A.D. 415-6), makes mention of the erection of a number of additional buildings attached to the temple of Svāmi Māhasena.

The facts disclosed by the inscriptions quoted above clearly show that the two Hindu cults of Śiva and Vishnu were in an advanced condition in the 5th Century A.D., so as to indicate that they must have had behind them many centuries of development.

Notes

- See Fig. 61, on p.110 of V.A. Smith’s History of Fine Arts in India and Ceylon. ↩︎

- Macdonell’s Sanskrit Literature, p.210 ↩︎

Read: Sri Aurobindo on Indian Sculpture

~ Design: Beloo Mehra