Volume VI, Issue 5

Author: Sisirkumar Ghose

Continued from Part 1

In the inner view of things the arts become a link between the visible and the invisible, between the real and the apparent. Why should this be so? One reason for this is because they are related to a theory of participation and potentiality. That is, all earthly beauty reveals itself as beauty by participation—in His essence.

In the Katha and Mundaka Upanishads we hear: tameva bhāntamanubhāti sarvaṁ tasya bhāsā sarvamidaṁ vibhāti, ‘All that shines here is but the shadow of His shining, all this universe is effulgent with His light.’ Or, in the simpler language of Tagore: The physical is the shadow of the psychic. More explicitly, “For the Indian mind form does not exist except as a creation of the spirit” (Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 270). The idea is not exclusively Indian, it is echoed in Plato and Plotinus, in nearly all mystical literature. Sri Aurobindo’s sonnet, The Divine Hearing, belongs to that living tradition, the language of heightened awareness, when

All sounds, all voices have become Thy voice:

Music and thunder, and the cry of birds,

Life’s babble of her sorrows and joys.

Cadence of human speech and murmured words,The laughter of the sea’s enormous mirth,

The winged plane purring through the conquered air,

The auto’s trumpet-song of speed to earth,

The machine’s reluctant drone, the siren’s blareBlowing upon the windy horn of Space

A call of distance and of mystery,

Memories of sun-bright lands and ocean-ways,—

All now are wonder-tones and themes of Thee.A secret harmony steals through the blind heart

And all grows beautiful because Thou art.

Watch ‘The Divine Hearing’

The companion poem, Divine Sight, confirms the same attitude and experience. Read the poem HERE.

Watch ‘Divine Sight’

From this “ecstasy of vision” to Indian iconography, to those ageless forms of cosmic powers and consciousness, is but a step. According to the Indian philosophy of worship, with which are closely allied the origins of art, the ishta devatā or chosen form of deity is but one’s own ideal self, svarupa. Through the appropriate ritual or contemplation, dhyāna, and worship, pujā, the devotee is enjoined to be at-one or identified with it. Essentially, it is the recovery of a lost identity: Thou art That.

The image one makes or worships is at once lamp and mirror. The embodiment is a chance for the embodied, not to be pooh-poohed, as is sometimes done by the extreme, intolerant ascetic schools. That would be poor psychology indeed. The emphasis on contemplation, dhyāna, preceding creation is part of the traditional theory. There are numerous texts in support. But the poet’s evidence, the artist’s natural concentration of energy before a work of art can actualize is more telling. Listen to The Stone Goddess:

In a town of gods, housed in a little shrine,

From sculptured limbs the Godhead looked at me,—

A living Presence, deathless and divine,

A Form that harboured all infinity.The great World-Mother and her mighty will

Inhabited the earth’s abysmal sleep,

Voiceless, omnipotent, inscrutable,

Mute in the desert and the sky and deep.Now veiled with mind she dwells and speaks no word,

Voiceless, inscrutable, omniscient,

Hiding until our soul has seen, has heard

The secret of her strange embodiment,One in the worshipper and the immobile shape,

A beauty and mystery flesh or stone can drape.

Watch ‘The Stone Goddess’

To understand this “beauty and mystery” one must know something of the cosmic self or consciousness. In The Indwelling Universal we are told:

All eyes that look on me are my sole eyes;

The one heart that beats within all breasts is mine.

But even here there are distinctions to make, depths within depths. The cosmic self or consciousness would seem to imply, if not depend on, the doctrine of the two souls or selves in man: There are two beings in my single self (Sri Aurobindo, The Dual Being).

There is still another. For, in its turn, it is supported by a total, moveless Calm and, on the peaks, by the Transcendence itself: My vast transcendence holds the cosmic whirl (Sri Aurobiondo, The Indwelling Universal).

In Cosmic Consciousness the poet tells us:

I have learned a close identity with all,

Yet am by nothing bound that I become;

A “deep spiritual calm…upholds the mystery of this Passion-play” or lila.

I housed within my heart the life of things,

All hearts athrob in the world I felt as mine;

I shared the joy that in creation sings

And drank its sorrow like a poignant wine.I have felt the anger in another’s breast,

All passions poured through my world-self their waves;

One love I shared in a million bosoms expressed.

I am the beast man slays, the beast he saves.I spread life’s burning wings of rapture and pain;

Black fire and gold fire strove towards one bliss:

I rose by them towards a supernal plane

Of power and love and deathless ecstasies.A deep spiritual calm no touch can sway

Upholds the mystery of this Passion-play. (Sri Aurobindo, Life-Unity)

* * *

It is the “secret touch” of the Ground Above that explains how I have become “what before Time I was” (Sri Aurobindo, The Self’s Infinity). And the Voice that now speaks is not that of the empirical ego but of a new centre of personality, one-with-all and with the Ground. It is during such hours or moments of encounter with Being that Watched by the inner Witness’ moveless peace are revealed

The heart of a world in which all hearts are one,

A Silence on the mountains of delight. (Sri Aurobindo, The Universal Incarnation)

This heart of a world is close to being world-free, to that sense of release or liberation, mukti, which the Indian mind has always believed to be the Final End of life. In the older view, art has, not unnaturally, been held to be conducive to freedom or salvation, muktipradayi. That it means or leads to a release from the ego and its restricting categories is a matter of immediate and universal experience.

The release does not come by any moral diktat or “criticism of life” but by earned vision, by, to use Eliot’s phrase, a raid on the absolute. On the borders of that Ineffable or anirvacaniya freedom becomes the food of the free, the hero’s meed:

My mind, my soul grow larger than all Space;

Time founders in that vastness glad and nude:

The body fades, an outline, a dim trace,

A memory in the spirit’s solitude.This universe is a vanishing circumstance

In the glory of a white infinity

Beautiful and bare for the Immortal’s dance,

House-room of my immense felicity.In the thrilled happy giant void within

Thought lost in light and passion drowned in bliss,

Changing into a stillness hyaline,

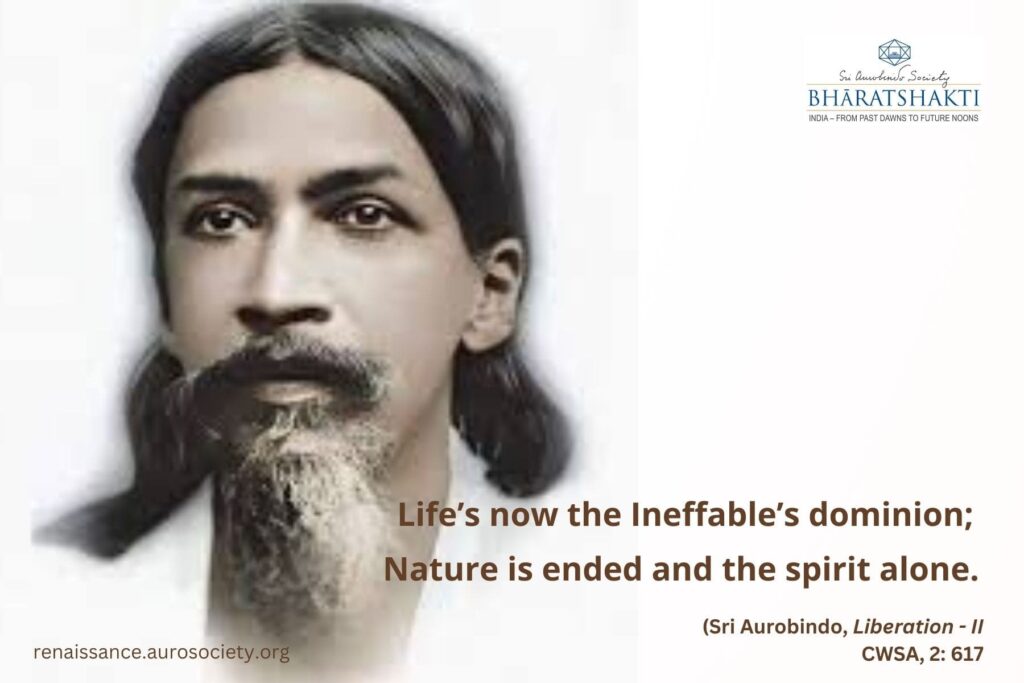

Obey the edict of the Eternal’s peace.Life’s now the Ineffable’s dominion;

Nature is ended and the spirit alone. (Sri Aurobindo, Liberation – II)

* * *

But this living on heights does not come easily and is hardly to be sustained for long. To the majority the “immense felicity” declares itself more often as an agony or a longing for the buried self—that Arnold knew so well—and which Sri Aurobindo has expressed thus:

A sacred yearning lingered in its trace,

The worship of a Presence and a Power

Too perfect to be held by death-bound hearts,

The prescience of a marvellous birth to come.Only a little the god-light can stay:

Spiritual beauty illumining human sight

Lines with its passion and mystery Matter’s mask

And squanders eternity on a beat of Time. (Savitri, CWSA, Vol. 33, p. 5)

To be concluded in Part 3

Read Part 1

~ Design: Beloo Mehra