Volume VI, Issue 4

Author: Beloo Mehra

E.B. Havell, the famous British art historian, said that a golden thread of Vedic thought bound together all varied strands of Indian art—Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, Sikh, and even Indo-Saracenic—in spite of their outer, theological, ritualistic and dogmatic differences. Also, because art is primarily subjective, it is not in existing monuments and masterpieces or in the fragmentary collections of painting and sculpture in museums that we should seek for the origin of the great art schools of the world. Rather, we should seek that in the thoughts which created these monuments and masterpieces, emphasises Havell.

“..it is undoubtedly true that in Greece, in Italy, in India, the greatest efflorescence of a national Art has been associated with the employment of the artistic genius to illustrate or adorn the thoughts and fancies or the temples and instruments of the national religion. This was not because Art is necessarily associated with the outward forms of religion, but because it was in the religion that men’s spiritual aspirations centred themselves.”

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 1, p. 450

In our ongoing exploration of the Spirit and Forms of Art in India, the focus has been on uncovering the deeper aspiration of Indian soul which has found expression in her various art forms over millennia. Especially starting with the issue on Indian temple architecture, we have emphasised a more experience-based account. And we have eschewed a dry academic analysis of Indian artistic traditions and art history where dates, dynasties, and details find center-stage. We have also kept in view the need for a variety; this allows us to more appropriately present the multiplicity of forms bound by one spirit. This current issue focused on Indian sculpture also follows the same flow.

A Visualisation

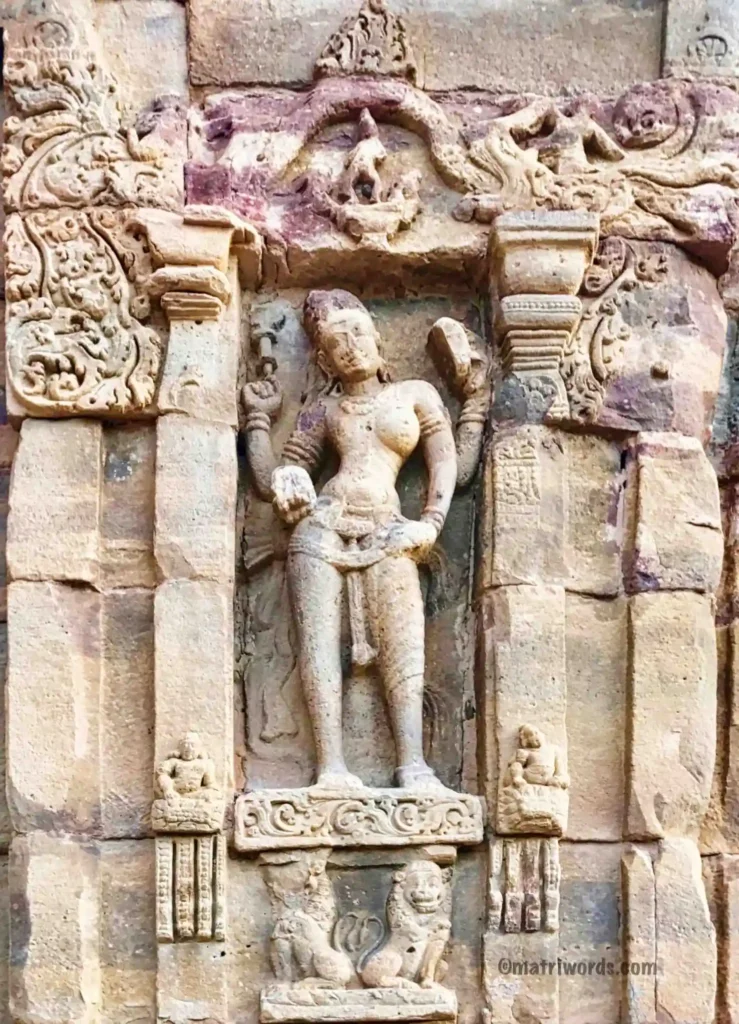

Picture yourself standing outside a grand temple, say, the famous Virupaksha temple at Pattadakal in Karnataka. Art history books will tell you that for about 200 years during the Chalukyan period (543-753 CE), Pattadakal, along with nearby Aihole and Badami became a major cultural center and religious site for innovation and experimentation in temple architecture. This gave the region the title — ‘cradle of Indian temple architecture’. Remarkable temple building activity happened particularly during the successive reigns of Vijayaditya (696-733 CE), Vikramaditya II (733-746 CE) and Kirtivarman II (746-753 CE).

But as you walk around this temple, and your eyes catch the niches on the temple’s outer walls, do you remember these details? What do you really see? There in those niches you meet both Lord Shiva and Lord Vishnu in their various rūpa-s such as Bhairava, Ardhanarishvara, Narasimha, and Hari-Hara. Are you seeing just the images, the beautiful sculptural art? Or is there something more that you see? Walking around the temple and ‘seeing’ the Lord manifesting Himself in each of these forms, a bhakta’s heart naturally bows down to one of the grandest visions of our ancestors. These were the visions of our Rishis who ‘saw’ the Truth of ‘One and Many’, ‘One in Many’ and ‘Many in One’ as one of the fundamentals of Sanatana Dharma.

* * *

* * *

You stand in front of each of these Shivas, and you don’t seem them merely as sculptures. These different rūpa-s of the Lord are embodied divinities, or rather One embodied divinity in Many forms, each unique and complete in itself. These are all living gods or One God becoming Many. And you recall these words of Sri Aurobindo describing an essential truth of Sanatana Dharma:

“…the worshipper of many gods still knows that all his divinities are forms, names, personalities and powers of the One; his gods proceed from the one Purusha, his goddesses are energies of the one divine Force.”

~ CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 192

Virupaksha temple is dedicated to Lord Shiva. But like most of the Shiva temples here also you find some marvelous representations of Lord Vishnu. One striking image of Harihara – the fused form of Vishnu as Hari and Shiva as Hara – catches your attention.

* * *

You stand in silence in front of Hari Hara. And Sri Aurobindo’s voice helps you understand the true meaning behind this form of the Divine:

“Rudra is the Deva or Deity ascending in the cosmos, Vishnu the same Deva or Deity helping and evoking the powers of the ascent.”

~ CWSA, Vol. 15, pp. 344-345

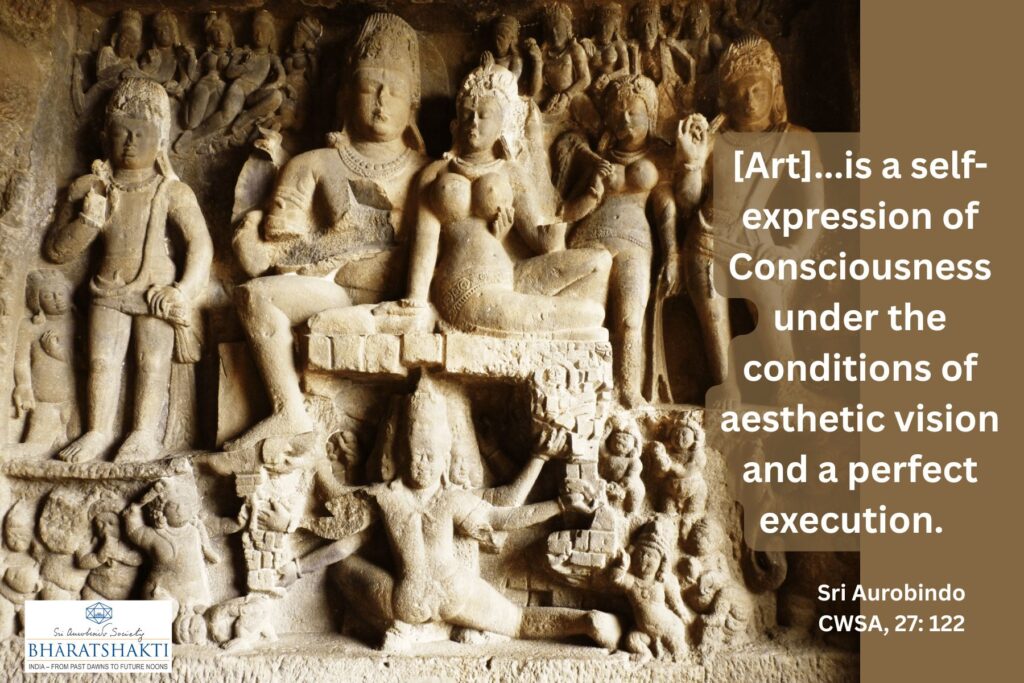

This is an experience of Art, the Indian way. Where a stone becomes God because the adorer of God carves Him or Her out of and in stone. Or in clay, in bronze. This is the art of sculpture in India, a long and rich tradition. Creating such art and appreciating such art requires not merely the knowledge of details — of iconography, technique, material. It requires a certain cultural training, a certain receptivity to the profounder truth being expressed through the object of art. It necessitates a readiness to experience the formless being expressed through form.

In this Issue

Sri Aurobindo, in his volume The Renaissance in India and Other Essays on Indian Culture, devotes a full essay on Indian sculpture (CWSA, Vol. 20, pp. 286-297). We find there an inspiring description of the profound intention and motive which guides Indian sculptural art. We also learn its deep and intimate connection with the spiritual and religious-philosophic vision which is at the source of all Indian cultural expressions. For the Guiding Light feature we highlight some selections from that chapter and present them in two parts.

In the feature titled From One Formless to Many Forms, we highlight selections from the book Indian Sculpture and Iconography: Forms and Measurements (2002). The book was published by Sri Aurobindo Society in collaboration with Vaastu Vedic Research Foundation, Chennai.

Closely linked with the sculptural heritage of India is the long tradition of image worship. We explore this through an excerpt taken from the book titled Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol. 1, Part 1.

Of Sculptures and Temples

To appreciate fully the sculptural tradition of India we have to see it in the context of the temple architectural tradition. The intimate connection between these two art forms – known together as vaastu parampara – is exemplified perfectly by Kailasha Temple at Ellora caves. This temple is essentially carved out like one big sculpture. A huge pile of hard rocky material was scooped out, revealing into form a two-storied beautiful temple.

Excavated from top to bottom, the entire monolithic cave-temple was planned at the beginning. It is said that no major part of this architectural marvel appears to have been an afterthought. Read Unearthing the Path: My Indian Story to know more about the Kailasha temple and the deeper story it may speak to a seeking heart.

* * *

The difference between the art of sculpture and the art of painting arises from the different kind of mentality required by the two arts. The material in which a sculptor works makes its own peculiar demand on the creative spirit and lays down its own natural conditions. In our next issue, we will focus on painting in India, but readers will find a preview to that in our offering titled Art in India: A Quick Historical Look – 2. (Read part 1 from October 2024 issue).

Our photo essay titled Tabo: A Lamp for the Kingdom takes the reader high up in Spiti valley near the border of Tibet. It gives a peek into a Buddhist monastery which is known as the ‘Ajanta of the Himalayas’.

With this issue we start a series titled ‘Sri Aurobindo on Indian Aesthetics.‘ This essay by Sisirkumar Ghose was first published in the 1968 issue of Sri Aurobindo Circle. We shall feature the full essay in three parts over the next few issues. In part 1, the author emphasises that Sri Aurobindo has not merely theorised about the deeply subjective and spiritual tradition of Indian aesthetics, but through his spiritual poetry he has actually renewed this sanatana tradition and made it a living truth for the modern sensibility.

We hope our readers will enjoy going through the various offerings in this issue. As always, we offer this work at the lotus feet of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother.

In gratitude,

Beloo Mehra (for Renaissance Editorial Team)