Volume VI, Issue 5

Author: Sri Aurobindo

Continued from PART 1

Spirit and Motive of Indian Painting

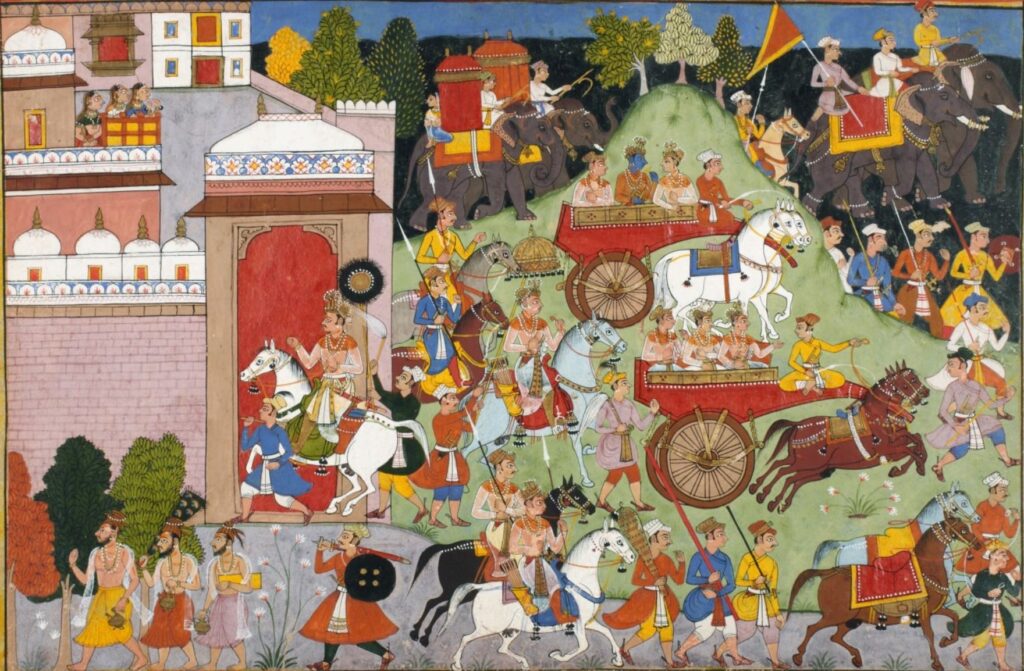

The spirit and motive of Indian painting are in their centre of conception and shaping force of sight identical with the inspiring vision of Indian sculpture. All Indian art is a throwing out of a certain profound self-vision formed by a going within to find out the secret significance of form and appearance, a discovery of the subject in one’s deeper self, the giving of soul-form to that vision and a remoulding of the material and natural shape to express the psychic truth of it with the greatest possible purity and power of outline and the greatest possible concentrated rhythmic unity of significance in all the parts of an indivisible artistic whole.

Take whatever masterpiece of Indian painting and we shall find these conditions aimed at and brought out into a triumphant beauty of suggestion and execution. The only difference from the other arts comes from the turn natural and inevitable to its own kind of aesthesis, from the moved and indulgent dwelling on what one might call the mobilities of the soul rather than on its static eternities, on the casting out of self into the grace and movement of psychic and vital life (subject always to the reserve and restraint necessary to all art) rather than on the holding back of life in the stabilities of the self and its eternal qualities and principles, guna and tattwa.

Essential Difference between the Art of Sculpture and Painting

This distinction is of the very essence of the difference between the work given to the sculptor and the painter, a difference imposed on them by the natural scope, turn, possibility of their instrument and medium. The sculptor must express always in static form; the idea of the spirit is cut out for him in mass and line, significant in the stability of its insistence, and he can lighten the weight of this insistence but not get rid of it or away from it; for him eternity seizes hold of time in its shapes and arrests it in the monumental spirit of stone or bronze.

The painter on the contrary lavishes his soul in colour and there is a liquidity in the form, a fluent grace of subtlety in the line he uses which imposes on him a more mobile and emotional way of self-expression. The more he gives us of the colour and changing form and emotion of the life of the soul, the more his work glows with beauty, masters the inner aesthetic sense and opens it to the thing his art better gives us than any other, the delight of the motion of the self out into a spiritually sensuous joy of beautiful shapes and the coloured radiances of existence.

***

Painting is naturally the most sensuous of the arts, and the highest greatness open to the painter is to spiritualise this sensuous appeal by making the most vivid outward beauty a revelation of subtle spiritual emotion so that the soul and the sense are at harmony in the deepest and finest richness of both and united in their satisfied consonant expression of the inner significances of things and life.

There is less of the austerity of Tapasya in his way of working, a less severely restrained expression of eternal things and of the fundamental truths behind the forms of things, but there is in compensation a moved wealth of psychic or warmth of vital suggestion, a lavish delight of the beauty of the play of the eternal in the moments of time and there the artist arrests it for us and makes moments of the life of the soul reflected in form of man or creature or incident or scene or Nature full of a permanent and opulent significance to our spiritual vision.

The art of the painter justifies visually to the spirit the search of the sense for delight by making it its own search for the pure intensities of meaning of the universal beauty it has revealed or hidden in creation; the indulgence of the eye’s desire in perfection of form and colour becomes an enlightenment of the inner being through the power of a certain spiritually aesthetic Ananda.

Inspiration for Indian Artist

The Indian artist lived in the light of an inspiration which imposed this greater aim on his art and his method sprang from its fountains and served it to the exclusion of any more earthly sensuous or outwardly imaginative aesthetic impulse.

The six limbs of his art, the ṣaḍaṅga, are common to all work in line and colour: they are the necessary elements and in their elements the great arts are the same everywhere; the distinction of forms, rūpabheda, proportion, arrangement of line and mass, design, harmony, perspective, pramāṇa, the emotion or aesthetic feeling expressed by the form, bhāva, the seeking for beauty and charm for the satisfaction of the aesthetic spirit, lāvaṇya, truth of the form and its suggestion, sādṛśya, the turn, combination, harmony of colours, varṇikābhaṅga, are the first constituents to which every successful work of art reduces itself in analysis.

Bharat Mata by Abananidranath Tagore

Read more on ṣaḍaṅga

But it is the turn given to each of the constituents which makes all the difference in the aim and effect of the technique and the source and character of the inner vision guiding the creative hand in their combination which makes all the difference in the spiritual value of the achievement, and the unique character of Indian painting, the peculiar appeal of the art of Ajanta springs from the remarkably inward, spiritual and psychic turn which was given to the artistic conception and method by the pervading genius of Indian culture.

Indian painting no more than Indian architecture and sculpture could escape from its absorbing motive, its transmuting atmosphere, the direct or subtle obsession of the mind that has been subtly and strangely changed, the eye that has been trained to see, not as others with only the external eye but by a constant communing of the mental parts and the inner vision with the self beyond mind and the spirit to which forms are only a transparent veil or a slight index of its own greater splendour. […]

The Governing Motive of Painting in India

The first primitive object of the art of painting is to illustrate life and Nature and at the lowest this becomes a more or less vigorous and original or conventionally faithful reproduction, but it rises in great hands to a revelation of the glory and beauty of the sensuous appeal of life or of the dramatic power and moving interest of character and emotion and action. That is a common form of aesthetic work in Europe; but in Indian art it is never the governing motive.

The sensuous appeal is there, but it is refined into only one and not the chief element of the richness of a soul of psychic grace and beauty which is for the Indian artist the true beauty, lāvaṇya: the dramatic motive is subordinated and made only a purely secondary element, only so much is given of character and action as will help to bring out the deeper spiritual or psychic feeling, bhāva, and all insistence or too prominent force of these more outwardly dynamic things is shunned, because that would externalise too much the spiritual emotion and take away from its intense purity by the interference of the grosser intensity which emotion puts on in the stress of the active outward nature.

The life depicted is the life of the soul and not, except as a form and a helping suggestion, the life of the vital being and the body. For the second more elevated aim of art is the interpretation or intuitive revelation of existence through the forms of life and Nature and it is this that is the starting-point of the Indian motive.

But the interpretation may proceed on the basis of the forms already given us by physical Nature and try to evoke by the form an idea, a truth of the spirit which starts from it as a suggestion and returns upon it for support, and the effort is then to correlate the form as it is to the physical eye with the truth which it evokes without overpassing the limits imposed by the appearance. This is the common method of occidental art always zealous for the immediate fidelity to Nature which is its idea of true correspondence, sādṛśya, but it is rejected by the Indian artist.

He begins from within, sees in his soul the thing he wishes to express or interpret and tries to discover the right line, colour and design of his intuition which, when it appears on the physical ground, is not a just and reminding reproduction of the line, colour and design of physical nature, but much rather what seems to us a psychical transmutation of the natural figure. In reality the shapes he paints are the forms of things as he has seen them in the psychical plane of experience: these are the soul-figures of which physical things are a gross representation and their purity and subtlety reveals at once what the physical masks by the thickness of its casings. The lines and colours sought here are the psychic lines and the psychic hues proper to the vision which the artist has gone into himself to discover.

This is the whole governing principle of the art which gives its stamp to every detail of an Indian painting and transforms the artist’s use of the six limbs of the canon.

Read PART 1

~ Design: Beloo Mehra