Volume VI, Issue 6

Author: Narendra Joshi

Editor’s Note: The author narrates a personal account of his journey of exploring Indian Art. He has been experimenting with traditional and digital visual arts. This has helped him develop a deeper appreciation and understanding of the innate genius unique to Indian aesthetic temperament.

My Journey Begins…

Ever since childhood, I loved sketching, painting and engaging in other arts. Mechanical and Manufacturing engineering education and professional experience in the industry and at the university level, helped develop this capacity more. I was especially interested in areas such as drawing, designing and drawing automation devices, CAD/CAM. These things provided greater skill in detailing, in understanding perspective, precision and handling of complexity.

It feels as if all this experience was destined to prepare me for what lay ahead. Over time I was drawn to replicate the wonders of Indian artistic heritage, using both conventional and digital mediums. Various types of mandalas and the breath-taking beauty and details of Indian temple architecture and iconography are my favourite subjects.

However, the decisive moment came during my full-time voluntary work in Northeast India.

That Moment

Place: Oyan village near Pasighat, in Arunachal Pradesh, Vivekananda Kendra school, somewhere in 1994-95. It was just after sunset when darkness was gradually spreading. I was too frustrated and exhausted to even get up and put on ‘lalten’, kerosene lamp, in my room. I was feeling completely lost in the research work I had taken up.

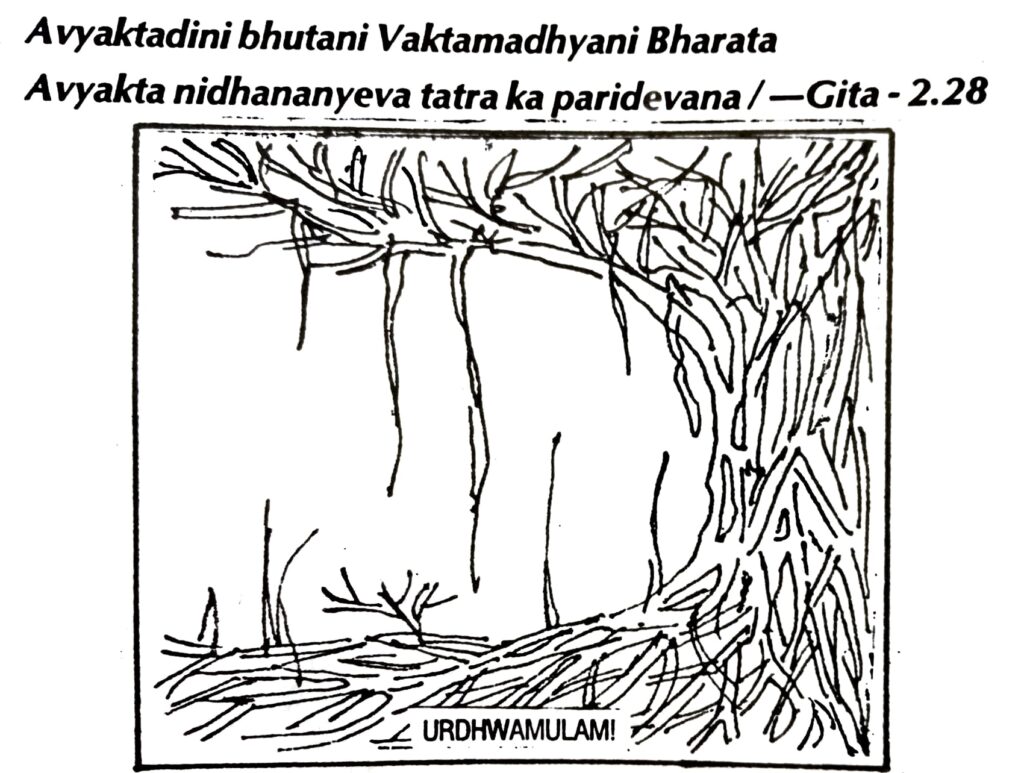

It was a moment of utter exhaustion, despair and silence. I was not getting any clue about joining all the voluminous and apparently disconnected pieces of data and experiences. I sat quietly and closed my eyes. Instinctively, to reduce this agony, I pulled out a piece of paper and drew a tiny sketch. Not sure what I was drawing, I went on.

After a while I saw a tree, an inverted tree. That sketch was sheer grace from above. It was also an immediate clue to my work — it was Ashwattha, the inverted tree in Upanishads and Gita. That became my central theme of connecting things together.

***

Sri Aurobindo’s volume, ‘The Foundations of Indian Culture’ was my guiding light throughout. ‘Ashwattha’ the book was published in 2000 by Vivekananda Kendra, Kanyakumari. I drew hundreds of sketches for this book. I was convinced by then that for such subjects, sketches are must. When reasoning does not help, articulation gets difficult, it is illustrations, it is art, which opens the doors.

During my time in the Northeast, I was not using much computer generated art, except for a few ideas I gave for textile design for our rural development unit. It was much later when I decided to reduce my time on mobile games that I discovered that drawing and painting sketches on mobile can be a better pastime than games or chat. During the last 15 years or so, it has almost become an everyday practice for me to draw sketches using different apps and tools on mobile, PC or iPad.

Conventional Art and Digital Art

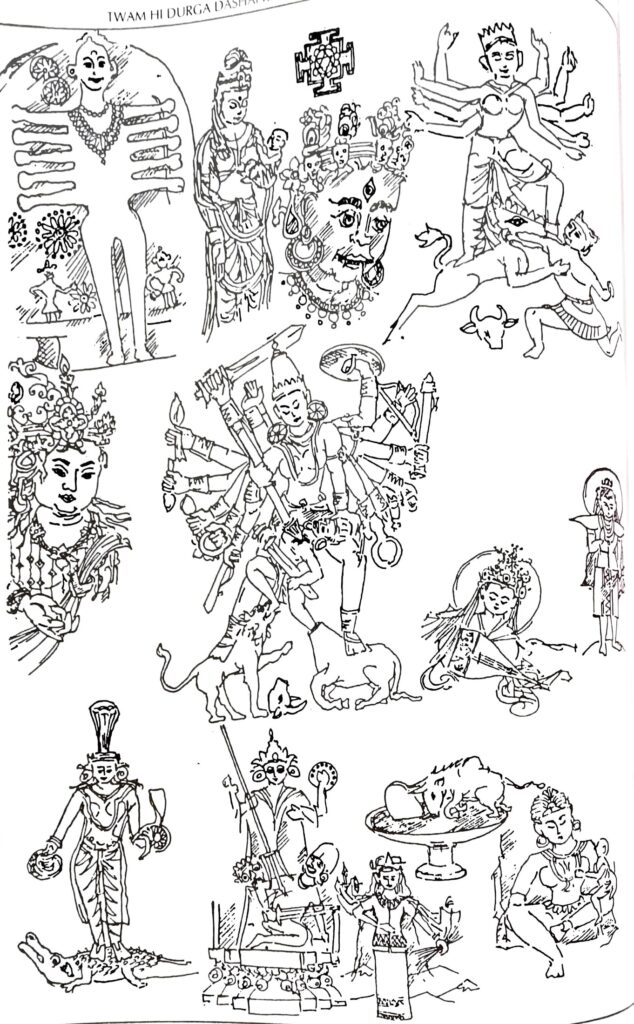

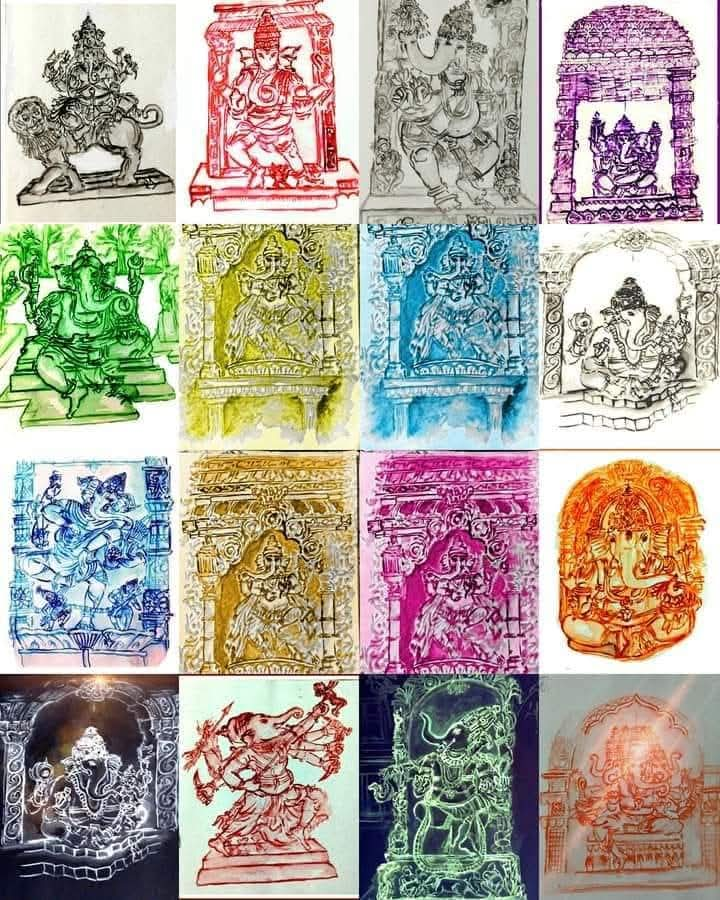

Most of my drawings, whether done by hand or digitally, include mandalas, landscapes, Ganesha, Shakti, Shiva, as well as abstracts. While I continue to do conventional water colour and poster colour painting and drawing, I have found digital art to offer some conveniences. For example, they require less space, time and instruments to start the work; there is a much greater possibility of undoing, redoing, and multiple editing. It is also easier to use polar and linear symmetry, scale change, perspectives; many types of brushes, pencils, colours, effects are available literally at my fingertips.

There are also some limitations. For example, when using conventional water colour, one can mix and spread colours more subtly. But use of thumb on touchscreen can be less delicate than actual brush. Puritans may say that conventional painting or sketching will always remain supreme expression in comparison to the digital art. Yet technology has allowed us several possibilities, and we ought to experience them. May be that’s what is now needed for present age and stage of mankind.

Insights from the Masters

As I look back on what I have learned through my experiences of art-creation, I find myself getting drawn to the insights I have gained from great masters such as Sri Aurobindo and Swami Vivekananda especially with regard to the spiritual, educational and national value of Art.

The pinnacle of Indian art belongs to the era when utility was not given higher value than morality and beauty. The sacred was not separated from secular and acute analysis was not devoid of alluring aesthetics. This was because they were harmonized at a higher level of consciousness which was reached in meditative moments. With his or her intense tapas, the artist, the mantrin and the yogi (many times all three would be the same person) would visualise a thing stationed at their elevated levels of consciousness and then effortlessly bring it down in expression through his/her well-trained craftsmanship.

Without such education, one was not qualified to be a sculptor, architect or a painter in India. Sri Aurobindo was emphatic to declare, “All art reposes on some unity and all its details, whether few and sparing or lavish and crowded and full, must go back to that unity and help its significance; otherwise it is not art” (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 274). He emphasised on the spiritual, educational and national value of art. Art is a beautiful means to elevate oneself through the aesthetic experience: rasa anubhuti, or rasa-bhava-ananda and by chittashuddhi or cleansing of mind, and as a precursor and ladder for the luminous ascent to the Infinite.

Watch a conversation on Art for Chittashuddhi

Swami Vivekananda said that in India everything is artistic: aesthetic sense in ingrained in us by samskaras of centuries. We can see evidence of this great artistic sense and the ‘raso vai saha’ conviction from the greatest temples and palaces to tiniest huts in tribal areas. Swamiji has spoken eloquently in many places about this peculiarity of Indian mind. The values inculcated in a child during formative years have their focus on moral as well as aesthetic development. At three levels: vichāra, ucchār and ācāra, thought, expression and conduct, are chastened through the Arts.

This was seen in Greek, Roman, Japan and other world cultures as well. Such integral vision reached to its miraculous depths especially in India. Nowadays, educating left side of the brain is much more emphasized; through mathematics, science and such subjects logical side of brain is cultivated. Much less is done for right side of the brain which cultivates idea generation, creativity, emotional maturity and aesthetic sense and intuition. The education in arts is meant for this. But sadly it is seen as only a small part of modern education. And it is mostly limited to serve only entertainment or relaxation.

This aesthetic side of a people’s culture is of the highest importance and demands almost as much scrutiny and carefulness of appreciation as the philosophy, religion and central formative ideas which have been the foundation of Indian life and of which much of the art and literature is a conscious expression in significant aesthetic forms.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 255

Mandala, the Pattern that Connects Everything

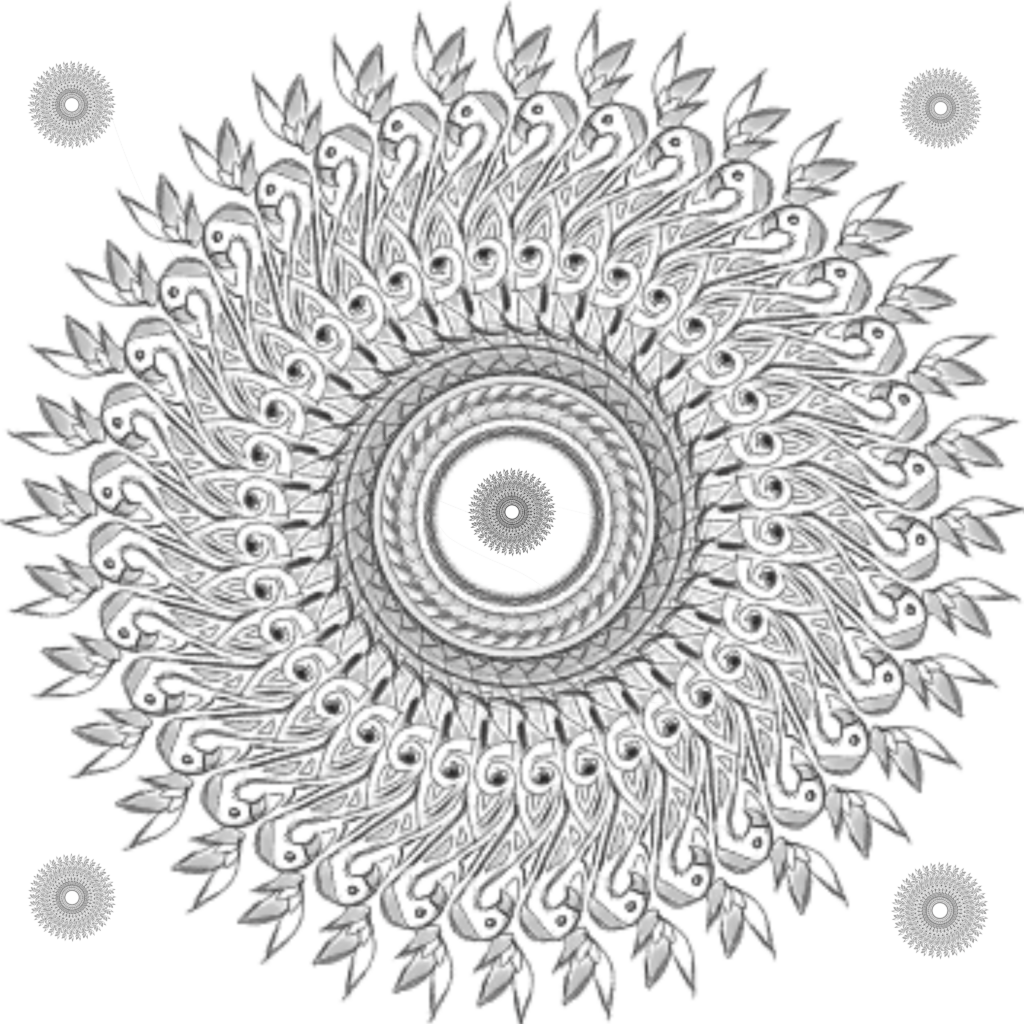

The act and practice of seeing, drawing, experiencing of Mandala designs is very significant in Indian culture. We see it in our rituals, in arts and architecture and, in Yoga. Our culture speaks of an Omnipresent Reality, a Pure existence which the Shakti is manifesting through powers such as Presence, Wisdom, Power, Beauty, and Harmony. One can see the importance given to mandalas across most of the mata-s, pantha-s, marga-s in Indian religio-spiritual traditions. This is so because the central idea behind the mandala is also embedded in patterns seen from microcosm to macrocosm, that is, at all levels from the smallest cell or molecule to trees, animals, human beings to the cosmos.

The peculiarity of a mandala is in its emphasis on relations which are more definitive than objects or points in creating or rather resulting in a typical pattern. In fact, relations intersect to define a point. Each has a place in relation to others and has a relation with the One. It is the joining: Dharma, Tantra, Sutra, that sustains.

This is seen not only in our arts, in sculptures and in our scripts, but can be seen in our social structures as well. Wherever a person is, he should be helped, allowed to rise up, step by step, grade by grade, without injuring others, without getting injured by others, as per his or her svabhāva, svadharma, samskāra and adhikāra.

Seamless Continuity in Expressions

Reflecting on mandalas we see a seamless continuity in expressions, from quantum science to painting, from iconography to dance, and from handicrafts and social systems. The pattern aims at repeating itself on different planes of consciousness, reminding us of the fractals and Mandelbrot series. This suggests the spiral evolution from Vyashti to Samashti, to Srishti and to Parameshti. It is evolution from child to old man, from Masyavatara to Buddhavatara, from Muladhara chakra to Sahasrar chakra, from Pinda to Brahmanda. This concept pervades in Yoga, Jyotisha, Tantra, Yajna and Puja, in temple architecture and even in the so-called tribal mysticism and animism.

***

The word Mandala sounds Sanskrit, but it has pierced the ranges of Himalaya through Buddhism and reached Tibet. It spread all over the so-called Mongolian belt and is seen vividly on their flags, paintings, prayer wheels, and in caves. It is notable in this context that the new paradigm in disciplines such as Physics, Ecology and Psychology emphasises inter-relatedness and inter-connectedness.

The latest discoveries in Quantum Physics as well as Astronomy support a Cosmic Design and Pattern Theory. Cosmos is not just made from building blocks of matter put on each other linearly. It is a web of interconnecting and intersecting relations. Capra tells us in ‘Uncommon Wisdom’: “I have learned from Chew that one can use different models to describe different aspects of reality without regarding anyone of them as fundamental. And those several interlocking models can form a coherent theory.”

Gregory Bateson emphasized on relations, not objects, and applied this new paradigm to ecology. Laing explained its application to medical practices and healing. They all were thrilled about the ‘Pattern that connects.’ Chew told Dr. Capra that intense concentration for prolonged period of time is the essence of any seeking, for continuity is crucial. One can use different models to describe different aspects of reality without regarding anyone of them as fundamental. And those several interlocking models can provide a coherent theory. In fact, it is now asserted that behind all apparent things in physical as well as mental world, there is a pattern that connects.

***

The importance of circle, cycle, series of cycles, gradual advance of elements through a cyclic motion of advance and relapse: all these are great favourites in Indian Culture, in her designs, dances and rituals. They must be so because they are simplified visual explanations of the most abstract principles. These cycles lead to rhythm, which is essential in tribal life as well as the later agro-based life.

The slow rhythmic continuous and curvilinear movements are required when making a pot, an ornament, to weave a cloth, or to process the food grains. The rhythm brought songs on the lips and also gave relaxation essential to allow work for a long time. This built-in relaxation and enjoyment avoided separate entertainment mechanisms which today have assumed demonic proportion.

The way the dancers join their hands in a typical tribal, Indian dance is same as the way the bamboo strips are joined to make a mat or an article and is also similar to how a weaving pattern looks. The relation is never 1-2 and 2-3. It is multiple, nonlinear and thus more beautiful, and perhaps more truthful as well.

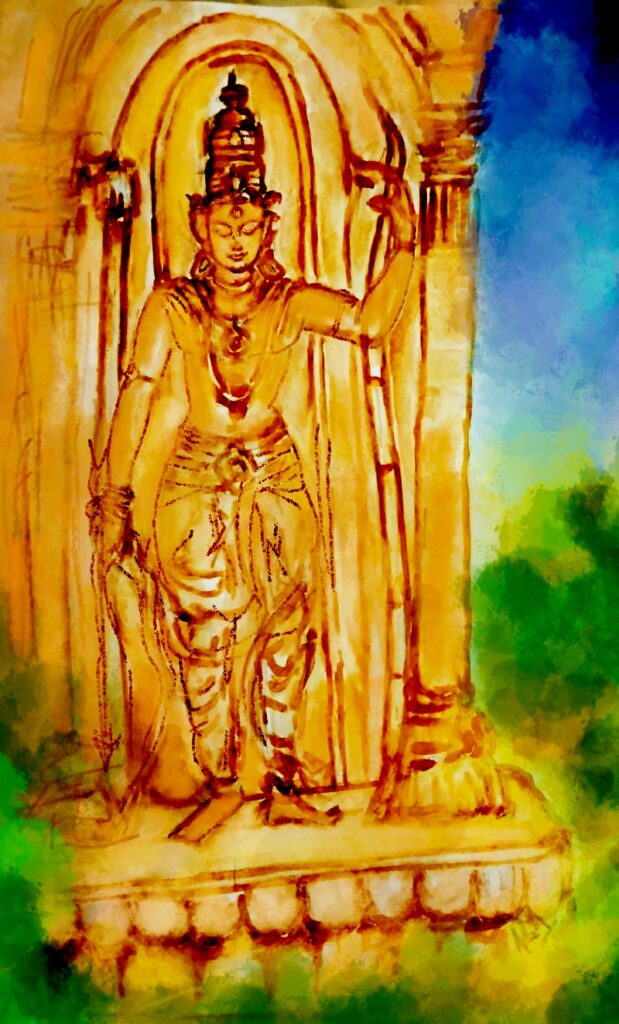

Reproducing Ancient Iconography, Cave and Temple Architecture

Whether it is at Ajanta, Kailasa mandir in Ellora, Kanheri, Elephanta or Madurai, Mahabalipuram, Suchindram, Padmanabhpuram, Hampi, or even at museums, the whole experience of recreating the wonder that is Indian temple architecture and iconography is deeply humbling and mesmerizing. It makes one truly internalize the truth, “Yato vacho nivartante, aprapya manasa saha”, there the vision, hearing, speech cannot go, nor can it be fathomed by mind.

These days when people visit these grand places, the first instinct for most of them is to take a picture on their mobiles. But for me, along with that immediate desire, the wonders of art there prompt me to reproduce it, draw it on a piece of paper or on digital device, in whatever capacity I can. One of the advantages is that while drawing I can draw complete figure in its totality even if it is found right now in partial, damaged, painfully broken condition.

***

I have also learnt that unless I draw it, say Nataraja or Ashtabhuja, Mahishasurmardini or Buddha, I am not fully able to absorb and completely completely ‘get’ the genius behind the form, its deeper meaning and spirit.

The balance, the grace, the delicacy, the fine details, the expression of tranquility, the beatific smile, the curves, the pose of tribhanga, or the layers of design in pillars or ceilings or kalasha of temple or its gopuram, the gandharvas and the dakshini, Avlokiteshwara, Tara, Ravan moving Kailasa, Shiva at Badami, the way multiple arms of the deities harmonise and create one whole impact — all this is to be experienced, and drawing them is the best way for me to do so. Those moments, at times days and hours, are like meditation for me, surely moments of deep concentration.

Exploring Art: A Work for the Indian Renaissance

Sri Aurobindo has given us detailed guideline for a true renaissance in India. He spoke of the need to recover the old spiritual knowledge in all its splendor, depth and fullness, and the flowing of Indian spirituality into new forms of philosophy, literature, art, science, and critical knowledge. The new possibilities in digital art, the possibilities of blending water colour, poster art with digital art, using pencils and pens whenever needed — all this, I believe, is opening doors as never before for expression of Indian soul.

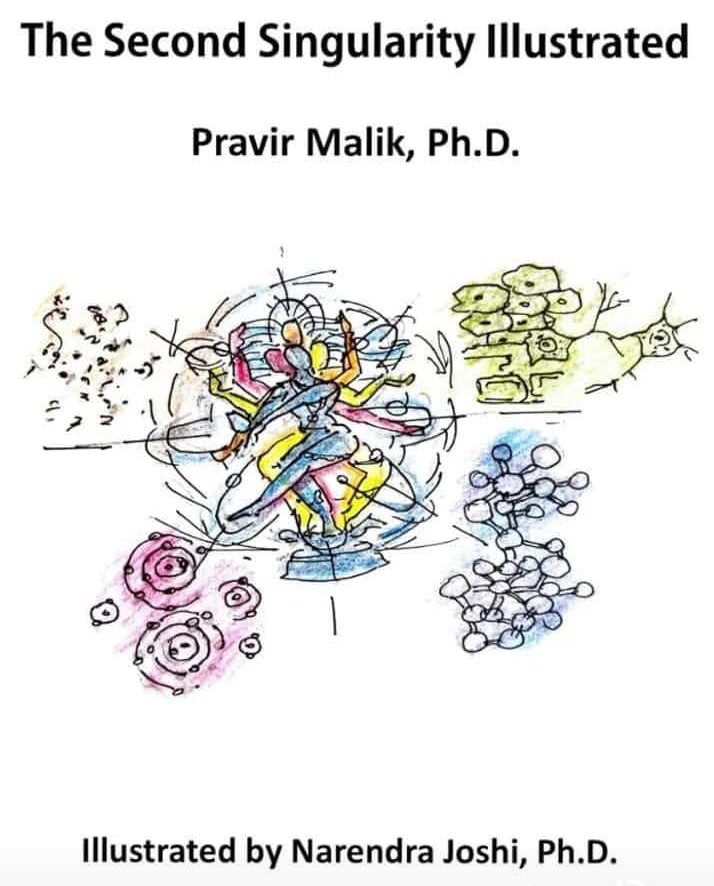

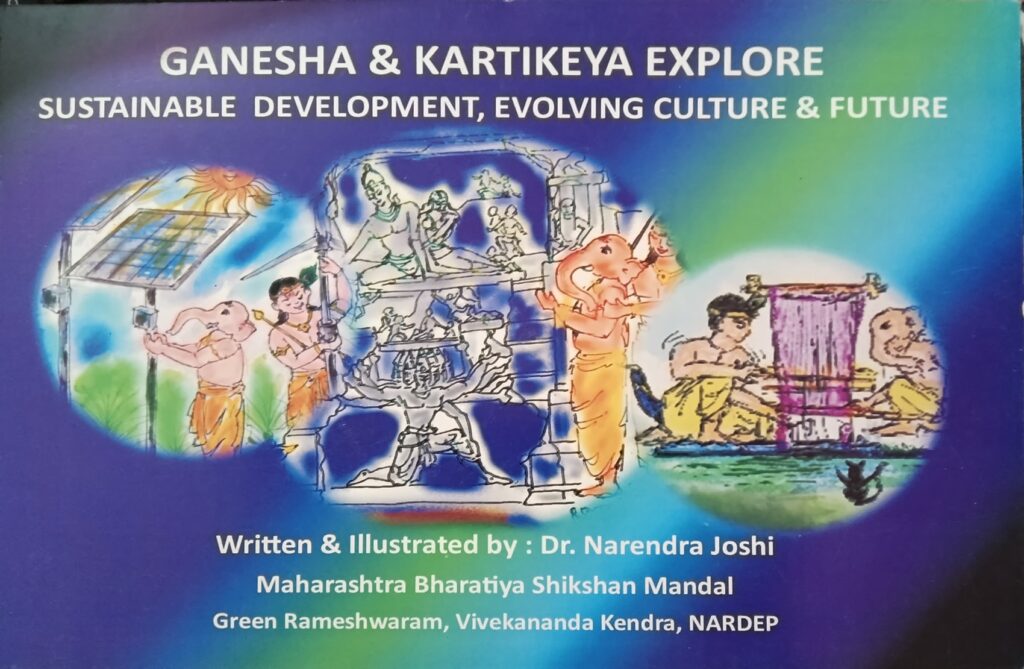

Some of my recent works include: a book which I wrote and illustrated based on the Ganesh & Kartikeya story with a message of sustainability and harmonising culture and development; illustrating a series of books in Cosmology of Light written by Dr. Pravir Malik; illustrating some of the all-time great songs in Marathi or Hindi. All this work is done in the spirit of an exploration, with an intent to discover the soul of the original artwork if I am trying to reproduce it, and through that the soul of India. Ultimately it is an exercise in finding a bit more of myself, and experiencing great joy and revelation in the process.

Feedback from others has helped to make many illustrations better. There is much to be learned and done yet. It is, after all, a homage paid to the Infinite through the means that are finite. The infinite unity on which all art reposes is surely to be reached through infinite diversity — like the innumerable diverse branches of Ashwattha which lead to the infinite roots above.