Volume VI, Issue 2

Author: Beloo Mehra

Editor’s Note: Sri Aurobindo says that soul realisation is the method of creation for an Indian artist. And naturally soul realisation must be the way of a our response to Indian art. What does this mean in practice? The author gives an account of her growing understanding of this with the help of a few examples.

“What Nature is, what God is, what man is can be triumphantly revealed in stone or on canvas.”

~ CWSA, Vol. 1, p. 451

Let us take a moment to meditate on this thought. It helps us to see that the stone or the canvas are indeed capable of revealing that what is not visible on the surface. That is what the best and the greatest artists in India have been able to do through their artistic creations. But they were not artists in the sense of the word we ordinarily understand. They were seers. The art they created was first ‘seen’ by them — in the stone or on the canvas.

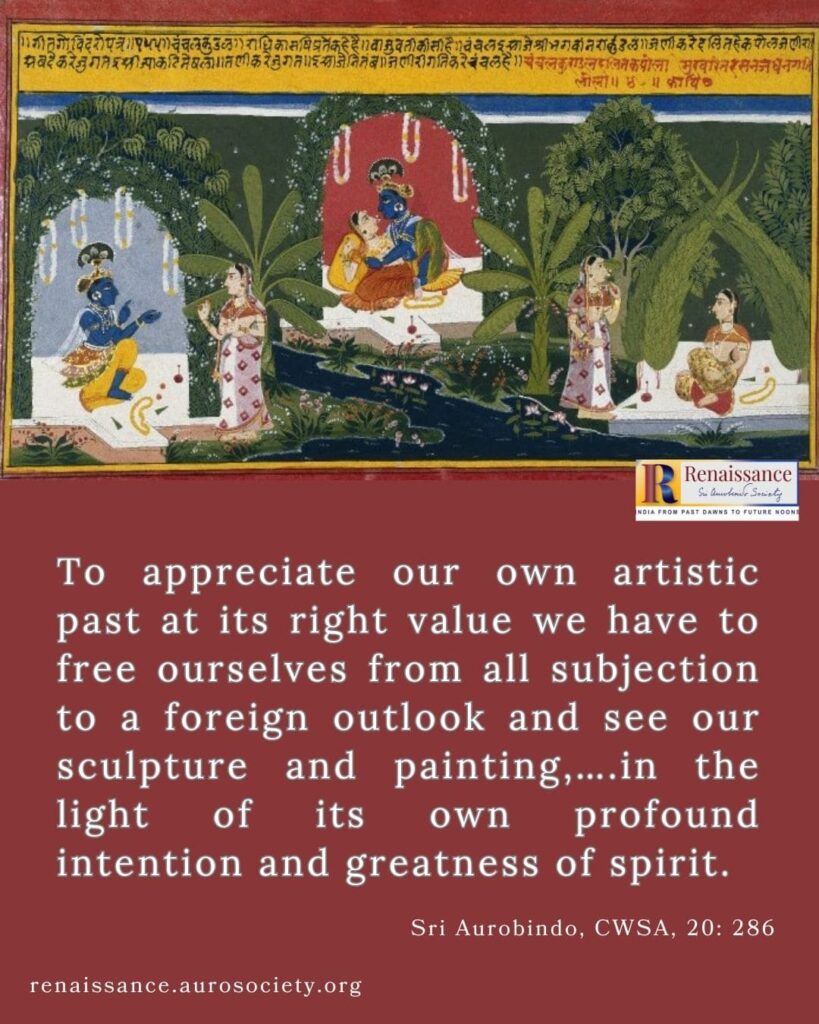

The great sculptors and temple builders of India carved or built what they saw. They had the vision of the divine hidden behind or perhaps within the stone or rock itself. Even after centuries of barbaric attacks on the artistic heritage of India, this land is peppered with outstanding works which of art which proudly speak of the greatness of artistic past of India.

How do we, the lovers of Indian art, the rasika-s, begin to ‘see’ such art?

Sri Aurobindo guides,

“Indian Art demands of the artist the power of communion with the soul of things, the sense of spiritual taking precedence of the sense of material beauty, and fidelity to the deeper vision within; of the lover of art it demands the power to see the spirit in things, the openness of mind to follow a developing tradition, and the sattwic passivity, discharged of prejudgments, which opens luminously to the secret intention of the picture and is patient to wait until it attains a perfect and profound divination.”

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 1, p. 467

How can we truly appreciate the best of Indian Art? First, one can never ignore the spirit, aim and essential motive from which this artistic creation starts. According to Sri Aurobindo, in the highest Indian art it is the spirit that carries the form. In contrast, in most Western art it is the form that carries whatever there may be of spirit.

For the Indian mind, Sri Aurobindo says, form does not exist except as a creation of the spirit. The form draws all its meaning and value from the spirit (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 270). The celebrated Indian painter S. H. Raza once explained the inner purpose of Indian art in a similar vein in an interview:

“A stone can represent divine power, and it can also be just the visual representation of a stone! So the question of finding the immense power of symbolism in Indian culture is one thing. To be dedicated to it in a romantic way, is entirely a different thing. Now it depends who the artists are that are working in this direction, and what they are trying to show.”

Cultural Training Necessary to Appreciate Indian Art

First, let us look at the predominant modern approach to art appreciation. The connoisseur first scrutinizes the technique, form and the obvious story behind the art. He or she then moves on to an appreciation of the beautiful or impressive emotion and idea which the artist is expressing. This is what the modern, rational mind understands as a way to appreciate art.

But in India, where the greatest of our visual arts have been very largely an aesthetic script of India’s spiritual, contemplative and religious experience, our approach to art appreciation must also be true to its highest and deepest spirit. In other words, we need an intuitive and spiritual eye to see the intuitive and spiritual art.

READ:

The Persistent Within the Transient

The temperament to appreciate beauty and art may be natural or acquired. But, Sri Aurobindo adds that to appreciate Indian art one must also go through a special kind of cultural training. This includes developing some fundamental attitudes towards existence, widening of the horizon and view of the spirit of Indian culture. It involves a shifting of the standpoint from which one sees and judges. Customarily we only catch what is at the surface level. We must shift to a deeper, more flexible vision and a more profound imagination. Otherwise we get only at the surface external idea, or at the most at things only just below the surface.

Technical appreciation and imaginative sympathy which try to understand art from outside are not enough. There is a need to identify with the creative insight and imaginative power of the artist. But more importantly, the rasika must grasp the spiritual meaning and atmosphere that the artist is seeking to express. One does it either through a total intuitive or revelatory impression or by some meditative dwelling (dhyāna) on the whole.

Also read:

“In India God is the All-beautiful…”

Ananda Coomaraswamy emphasises that in such aesthetic contemplation, we momentarily recover the unity of our being. There is, as if, a temporary release from individuality. This is something akin to what happens when one experiences deep love. Only in identification with God can one discover and experience Absolute Beauty.

The very nature of Art is rhythm and harmony, says Nolini Kanta Gupta (Collected Works of Nolini Kanta Gupta, Vol. 2, p 358) . And if the Divine is integral harmony and perfect rhythm, it is the element of divine harmony and rhythm which is the measure of the beautiful in Art. To discern and feel such harmony and rhythm has to be part of the rasika‘s training in art appreciation.

A rasika of Indian art should not see solely with the physical eye informed by reason and aesthetic imagination. One must make the physical seeing a passage to the opening of the inner spiritual eye and a moved communion in the soul. Furthermore, it is not sufficient to appreciate the technique and the fervour of religious feeling.

In order to identify oneself with the whole purpose of the artist, one must be able to feel the spiritual intention that is served by the technique. One must be able to intuitively discern the psychic significance of each line and colour the artist has used to express a specific religious emotion or contemplative experience.

As Sri Aurobindo explains succinctly:

“A great oriental work of art does not easily reveal its secret to one who comes to it solely in a mood of aesthetic curiosity or with a considering critical objective mind, still less as the cultivated and interested tourist passing among strange and foreign things; but it has to be seen in loneliness, in the solitude of one’s self, in moments when one is capable of long and deep meditation and as little weighted as possible with the conventions of material life.”

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, pp. 271-272

Spirit and Form

Sri Aurobindo writes:

“All great artistic work proceeds from an act of intuition, not really an intellectual idea or a splendid imagination,— these are only mental translations,— but a direct intuition of some truth of life or being, some significant form of that truth, some development of it in the mind of man.”

~ CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 266

However, there still remains immense divergence between different cultural forms of art because of various significant differences. These differences can be in the:

- object and field of the intuitive vision,

- method of working out the sight or suggestion,

- rendering by the external form and technique,

- whole way of the rendering to the human mind, and

- centre of our being to which the work appeals.

The first point of difference is most significant, says Sri Aurobindo.

In most western classical art, particularly of the realist and naturalist schools, the object and field of creative intuition is limited to Life and Nature. The artist sees only the outer aspects of Life and Nature such as action, passion, emotion, or idea, and expresses the aesthetic delight in them.

Such art appeals more directly to the outward soul by a strong awakening of the sensuous, the vital, the emotional, the intellectual and imaginative being. It is not directed to the eye of the deepest self and spirit within. The spiritual component in such work is limited to as much or as little that is suitable to the outward form. And that is what expresses itself through the outward form. This is also true of some of the later schools which have emphasized seeing beyond the outer surface.

It is the form which attracts and arrests the modern, rational, westernized mind. Such a mind lingers on the form and cannot get away from its charm. It loves the form for its own beauty, rests on the emotional, intellectual, aesthetic suggestions that arise directly from its most visible language. And in this process, it confines the soul in the body. For such a mind, form creates the spirit. The spirit depends on the form for its existence and for everything it has to say.

Continued in PART 2

~ Design: Beloo Mehra