Volume VI, Issue 2

Author: Beloo Mehra

Continued from PART 1

It is important to recognize that the words ‘Indian’ and ‘Western’ are not used here in the sense of a geographical marker but rather as a representative of a particular outlook on life, existence, reality, knowledge, truth, and of course, Art. It is these ‘cultural’ differences or characteristics which carry themselves into the representative art of the culture as well as its predominant artistic process itself.

‘Indian’ in our discussion here refers to a more integral approach where Spirit is not removed from Life and Matter, just hidden, and hence all Life and Art become a means to express and unveil that hidden spirit. And the word ‘Western’ is used in the sense of a rational-materialistic approach to Life and Art, which views Spirit as something outside, something separate from Life and Nature.

The theory of ancient Indian art at its greatest is of another kind.

And Sri Aurobindo reminds that it is the greatest art which gives its character to the rest and throws on it something of its stamp and influence.

Read:

The Aims of Indian Art

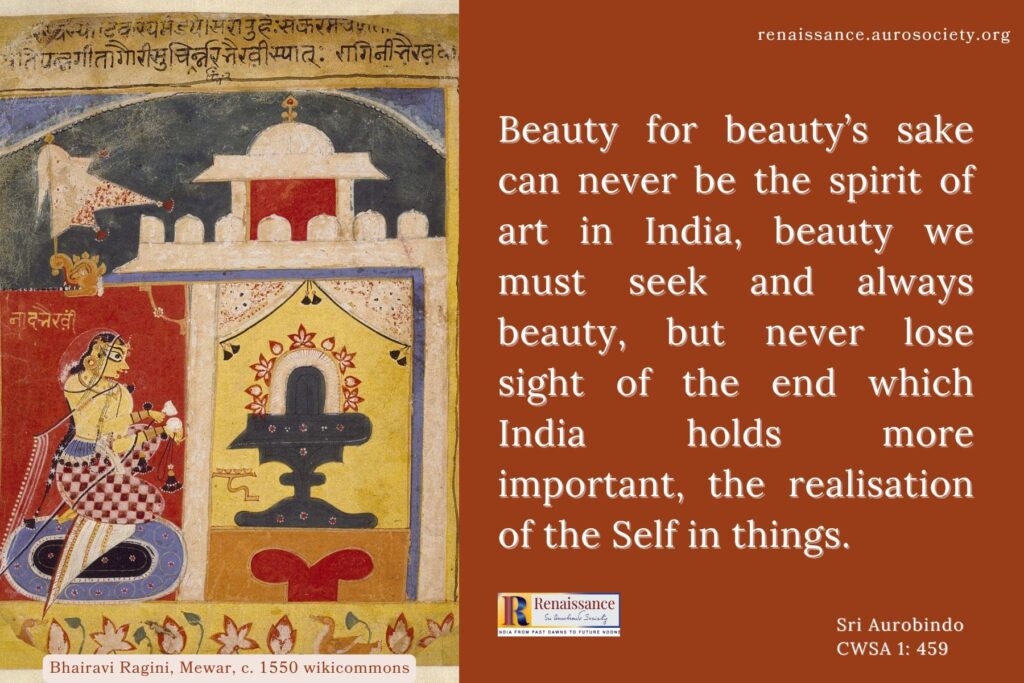

Reality for its own sake is not the ideal of Indian art. The highest ideal of an artist that Indian culture presents is of one who sees with an inner vision the true reality which is hidden. Of course, not all Indian work realizes this ideal. There is plenty of art in India which falls short, it is either ineffective or even debased. But Sri Aurobindo emphasizes that we must judge and appreciate by the highest examples because it is the best which give the most characteristic influence and tone to the essential artistic sensibility of a people.

The highest Indian art is identical in its spiritual aim and principle with the rest of Indian culture. This spiritual aim is not forgotten even when the artist is representing something from the level of material world, the outer life of man and the things of external Nature. But beauty for beauty’s sake can also never be the spirit of art in India. As Sri Aurobindo puts it, beauty we must seek and always beauty, but we must never lose sight of the end which India holds more important, the realization of the Self in things.

Also read:

Soul-realisation – The Method of Artistic Creation

In most good works of Indian art, there is always something more in which the material presentation of life floats as in an immaterial atmosphere. Life is seen in some suggestion of the infinite or of something beyond. Or there is at least a touch and influence of these which helps to shape the presentation. To truly appreciate such art, a rasika has to develop the intuitive and inner vision.

According to Sri Aurobindo, when we see a great work of Indian art – be it a painting or a sculpture – the truth, the exact likeness or resemblance is there, known as sādṛśya, the correspondence to the form. But it is the correspondence to the truth of the essence of the form, not necessarily the outer details, “…it is the likeness of the soul to itself, the reproduction of the subtle embodiment which is the basis of the physical embodiment, the purer and finer subtle body of an object which is the very expression of its own essential nature, svabhāva.” (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 308).

The means by which this effect is produced is characteristic of the inward vision of the Indian mind. The two examples given below illustrate this rather well.

In example 1 we see the inner equanimity and calm of Sri Rama, his deep inner beauty which charms all who enter into the depth of his story, the Ramayana. All this and more are captured in the simple sketch, and particularly expressed through that extremely loving gaze of Ram into the Infinite, making him one with Infinite that He is.

Example 1

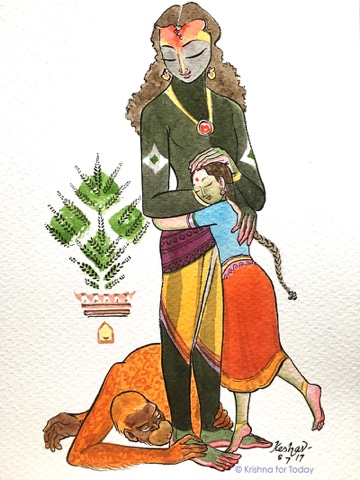

In example 2, we find another kind of gaze of the Infinite, the One. Here we meet Sri Krishna embracing his friend and student, Arjuna in the most loving and protecting way. It is an embrace which soothes and calms, which tells Arjuna (and us) that all is well, all will be well.

The expression on the face of Arjuna, the human disciple, captures so beautifully the liberating force of the Love of Sri Krishna, his Divine Teacher. Meditating on this expression reveals to us that we too, if we are open to it, can experience the delight of such Love through the force of the verses of the Bhagavad Gita, the dialogue of the Divine Teacher with the Human Disciple.

Example 2

This is how sādṛśya works, I suppose. It is consciously facilitated by the artist who is in touch the essence of Indian culture, the Indian way of being, the inner way of being. And he or she does it by a bold and firm insistence on the pure and strong outline and a total suppression of everything that would interfere with its boldness, strength and purity or would blur over and dilute the intense significance of the line.

For example, as Sri Aurobindo explains, in the treatment of the human figure, an Indian artist pays attention to the following:

- all corporeal filling in of the outline by insistence on the flesh, the muscle, the anatomical detail is minimised or disregarded;

- the strong subtle lines and pure shapes which make the humanity of the human form are alone brought into relief;

- the whole essential human being is there, the divinity that has taken this garb of the spirit to the eye, but not the superfluous physicality which he carries with him as his burden.

- It is the ideal psychical figure and body of man and woman that is before us in its charm and beauty. (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 308)

We see this illustrated rather nicely in the next few examples.

Example 3

Example 4

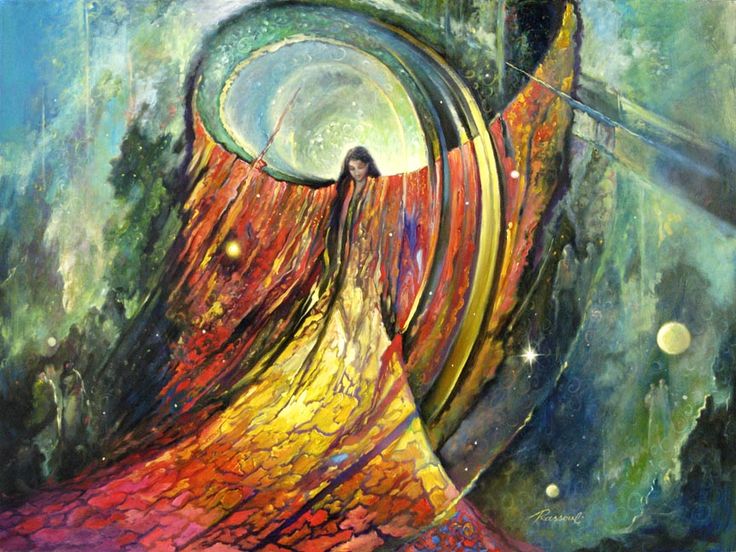

An inner aim and vision govern the work of the Indian artist even when he or she is creating the figures of ordinary human beings. As Sri Aurobindo explains, the focus is not to portray some dramatic action or a character portrait, but to embody rather a soul state or experience or deeper soul quality.

For example, in the figure of a saint or a devotee it is not the outward emotion, but the inner soul-side of rapt ecstasy of adoration and God-vision which the artist is trying to express through the creation. This emphasis on expression of an inner soul quality or experience is what makes all Indian art unique.

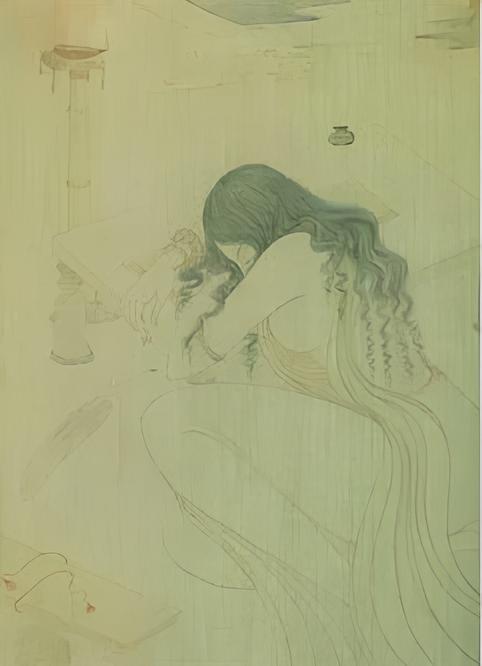

The next two examples give us a sense of what this expression of inner soul experience might look like.

Examples 5 & 6

In example 5 we meet the Lord with his true bhaktas, his lovers, his premi-s – Andal, Shri (Tulsi) and the ever-loyal Hanuman. And in example 6, we see another expression of love, the very human love, the pining and longing of a maiden in love. While these two works have a long difference of several decades between them, both capture the essential seeking of Love – the seeking for eternity and for intensity, which as Sri Aurobindo notes, “is instinctive and self-born in the relation of the Lover and Beloved.” (CWSA, Vol. 23, p. 569)

This is how one can slowly develop an inner sensitivity and seeing to appreciate Indian art. And I continue to do this with Sri Aurobindo as my guide and guru.

READ PART 1

Author’s Note: An earlier version of this article was published in New Race: Journal of Integral Studies, Volume 5, Issue 3 (2019).

~ Design: Beloo Mehra