Volume III, Issue 2

Author: Sri Aurobindo

Editor’s note: Featured here is a selection from a longer incomplete piece written by Sri Aurobindo, around 1910-13. Drawing upon some key insights from Hindu scriptures, Sri Aurobindo explains that the Hindu mind has never admitted the principle of linear progress in Nature.

Slight formatting changes such as shortening the paragraphs and adding sub-headings are made for the ease of online readability.

. . .the Hindu mind has never admitted the principle in Nature of progress in a straight line. Progress in a straight line only appears to occur and so appears only because we concentrate our scrutiny on limited sections of the curve that Nature is following.

But if we stand away from this too near and detailed scrutiny and look at the world in its large masses, we perceive that its journeying forward has no straightness in it of any kind but is rather effected in a series of cycles of which the net result is progress.

Two Images of Progress: Ship on Water and Planets in Space

The image of this apparent straight line is that of the ship which seems to its crew to be journeying on the even plain of the waters but is really describing the curve of the earth in a way perceptible only to a more distant and instructed vision. Moreover even the small section of the curve which we are examining & which to our limited vision seems to be a straight line is the result of a series of zigzags and is caused by the conflict of forces arriving by a continual struggle at a continual compromise or working out by their prolonged discord a temporary harmony.

The image of the actual progress in cycles is the voyaging in Space of the planets which describe always the same curve round their flaming & luminous sun, image of the perfect strength, joy, beauty, beneficence and knowledge towards which our evolution yearns. The cycle is always the same ellipse, yet by the simultaneous movement of the whole system the completed round finds the planet at a more advanced station in Space than its preceding journey.

It is in this way, by an ever-swaying battle, a prodigal destruction and construction, a labouring forward in ever-progressing curves and ellipses that Nature advances to her secret consummation.

These are the conceptions we find expressed in the Puranic symbols familiar to our imagination.

Ancient Hindu Symbols of Cyclical Progress

There is the Kalpa of a thousand ages with its term of fourteen Manwantaras dividing a sub-cycle of a hundred chaturyugas; there is the dharma, the well-harmonised law of being, perfect in the golden period of the Satya, impaired progressively in bronze Treta and copper Dwapara, collapsing in the iron Kali only to open the way by its disintegration to the manifestation in the next Satya of the old law, truth or natural principle of existence arranged in a new harmony.

There is throughout this zigzag, this rhythm of rise and fall and rise again brought about by the struggle of upward, downward and stationary forces.

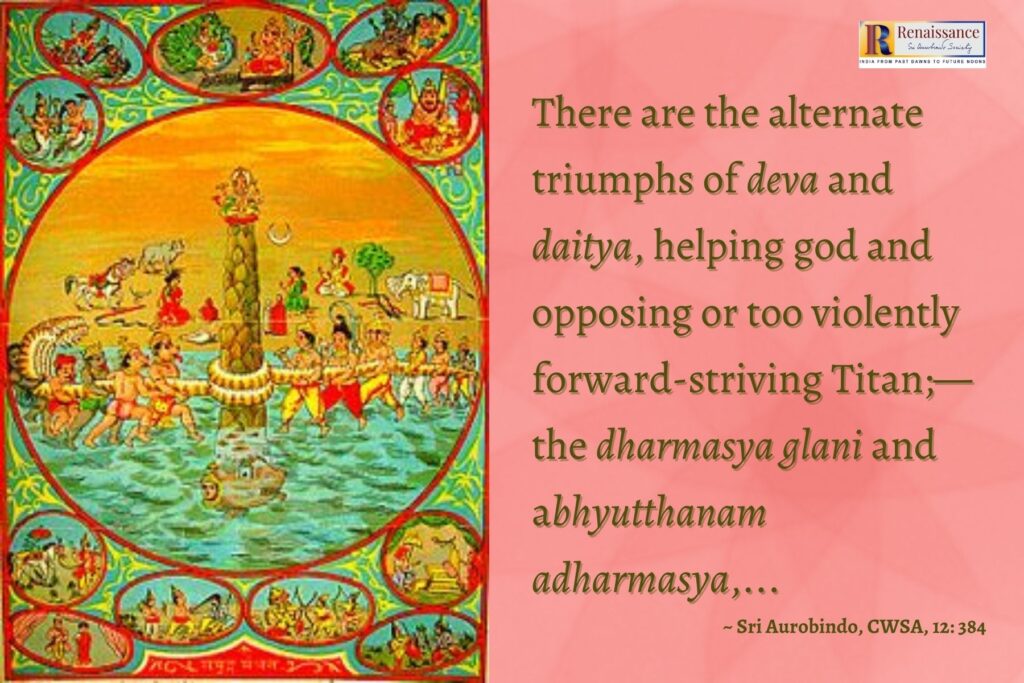

There are the alternate triumphs of deva and daitya, helping god and opposing or too violently forward-striving Titan;—the dharmasya glani and abhyutthanam adharmasya, when harmony is denied and discord or wrong harmony established, and then the Avatara and the dharmasya sansthapanam, eternal Light and Force descending, restoring, effecting a new temporary adjustment of the world’s ways to the truth of things and of man.

World History Full of the Alternately Triumphant Forces of Progress and Regression

Translated into more modern but not necessarily more accurate language these symbols point us to a world history not full of the continual, ideal, straightforward victory of good and truth, not progress conceived as the Europeans conceive it, a continual joyous gallop through new & ever new changes to an increasing perfection, but rather of the alternately triumphant forces of progress and regression, a toiling forward and a sliding backward,—the continual revolution of human nature upon itself which yet undoubtedly has but conceals & seems not to have its secret of definite aim and ultimate exultant victory.

Evolution in Vedanta

In certain respects the old Vedantic thinkers anticipate us; they agree with all that is essential in our modern ideas of evolution. From one side all forms of creatures are developed; some kind of physical evolution from the animal to the human body is admitted in the Aitareya.

The Taittiriya suggests the psychological progress of man, and the psychological progress of race cannot be different in principle from the evolution of the individual—a proceeding from the material, the emotionally and mentally inert man upwards [through] the mental to [our] spiritual fulfilment.

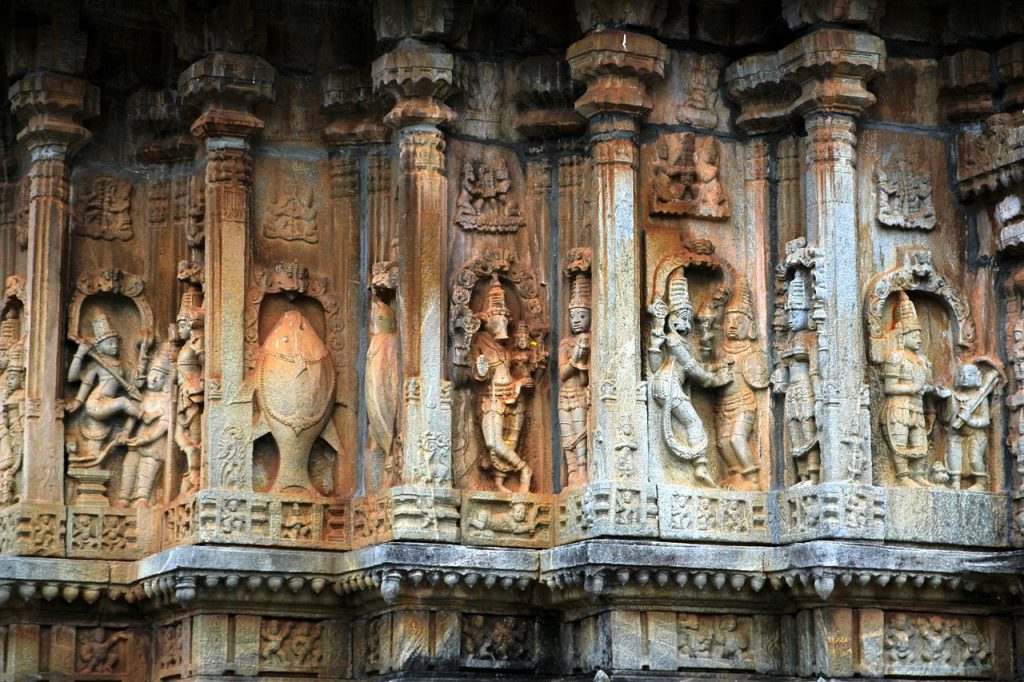

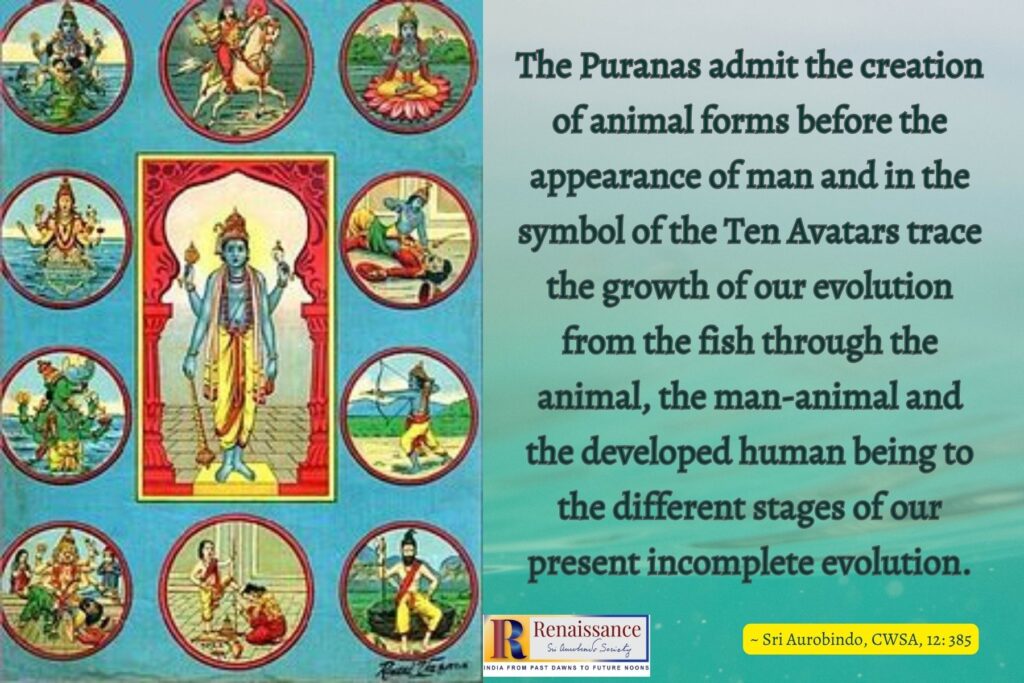

Daśāvatāra and Evolution

The Puranas admit the creation of animal forms before the appearance of man and in the symbol of the Ten Avatars trace the growth of our evolution from the fish through the animal, the man-animal and the developed human being to the different stages of our present incomplete evolution.

But the ancient Hindu, it is clear, envisaged this progression as an enormous secular movement covering more ages than we can easily count. He believed that Nature has repeated it over & over again, as indeed it is probable that she has done, resuming briefly & in sum at each start what she had previously accomplished in detail, slowly & with labour.

Perpetually Self-repeating, Perpetually Progressing Cycles

It is this great secular movement in cycles, perpetually self-repeating, yet perpetually progressing, which is imaged and set forth for us in the symbols of the Puranas. It is for this reason that he assigned to his civilisation those immense eras and those ancient and far backward beginnings which strike the modern as so incredible. He may have erred; recent discoveries & indications are increasingly tending to convince us that nineteenth century scholarship has erred equally in the opposite direction.

Translated again into modern language the Hindu idea of the chaturyuga, four Ages, with all the attendant Puranic circumstances persists as the tradition of a period just such as has been postulated, a period of natural and perfect poise in his knowledge, action and temper between man and his environment.

The ideas, the knowledge, the temper, the spirit of this great epoch of civilisation,—but not its institutions or practices—is preserved for us in the Veda and Vedanta, and all existing human societies, civilised or barbarous, go back for the origins of their thought, character & effort to the general type of humanity that was then formed.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 12, pp. 383-386

~ Graphic design: Biswajita Mohapatra and Beloo Mehra