Volume I, Issue 1

Author: Sisir Kumar Mitra

Continued from Part 1

The Incomparable Political Genius of India

As we glance through the pages of Sri Aurobindo’s four essays on ancient Indian Polity, included in ‘The Renaissance in India and Other Essays on Indian Culture’, we feel transported back to those splendid days of our past when India showed her incomparable political genius.

Her genius reflected in the building up of powerful republics and vast empires and in administering them with superb efficiency and in accordance with the spiritual bent of her mind, enabling the free individuals in them to live up to the highest ideals of the race, so that there might grow up a collectivity comprising such individuals, and moving towards a perfect form through the perfection of its human constituents.

Where is the text-book that has dealt with this deeper truth underlying India’s political endeavours? Foreign writers have distorted facts and desecrated the pages of Indian history with fabrications in order to prove to the world the weakness of our ancient corporate organisations, and our incapacity to govern and build up any homogeneous and progressive body-politic.

Even some of our own scholars are not free from such false notions. Moreover, these ideas find support in another wrong view, also widely held, that India had her attention always fixed on the contemplation of the Spirit to the total exclusion of the things of life.

Sri Aurobindo’s luminous essays are a flat contradiction of such myths. They expose and nail to the counter once for all the utter absurdity of such statements. If India was great in her spiritual achievements, she was no less great in her material pursuits, for she regarded them, according to the Arthaśāstra, as the basic condition of her spiritual endeavours.

India would not have been able to live the rich and colourful life that she has lived through the ages, had her people rejected life as a mere illusion. But, on the contrary, life had no meaning for her if it was denied the scope for the fulfilment of its spiritual possibilities.

How has India managed to have such a long and chequered existence in history and what is the direction of her future?

The Soul-Idea

There is in every people a common soul, mind and body. And like the individual man, a people – a collectivity of individuals – also passes through the cycle of birth, growth and decline. And, if at the last stage the soul or the life-force of a collective becomes incapable of a recovery or a renewal, it dwindles and slowly makes its final exit from the world. In this way have passed away many of the ancient peoples who are only remembered in history as the builders of great civilisations.

It is a soul idea or a life idea that really governs and inspires the activities of a people. In the history of the world China and India are the only countries with a more or less unbroken record of ceaseless creative strivings. It is these two ancient peoples alone that have retained their old strength and energy and are able to make ever-new endeavours not unworthy of the greatness of their heritage.

In the case of the Chinese this is so because of the indomitable power of life that sustains and guides them towards their high destiny in the future, and in the case of India, because the immortal spirit of her collective being and her inexhaustible creative energy have never failed her whenever after a spell of inactivity or lassitude, she has made an attempt to ascend to a new and higher summit of glory.

India’s ancient seers envisaged in her the Mother, the Infinite and Compassionate Mother of man, a conscious formation of the Supreme Shakti. And her history shows how true this vision has been. The spiritual mind of India, says Sri Aurobindo, regarded life as a manifestation of the Self, the people as a life-body of Brahman in the samasti, the collectivity, the collective Narayana; the individual as Brahman in the vyasti, the separate jīva, the individual Narayana.

If the physical form of India embodies the Shakti, her human content incarnates Brahman. But to the Tantriks, everything that exists is a form of the Shakti, and to the Vedantin, Brahman pervades everything. And these two ideas find their identity in the transcendent vision of that creative power of Sacchidānanda which is ever behind every endeavour of evolutionary Nature to prepare man for a divine existence upon earth.

In the acceleration of this all-important preparation India has already taken a lead. It is a goal towards which she is destined to lead mankind by her already acquired spiritual power. That is why after a brief slumber she is again having a new resurgence of her soul.

That is why Sri Aurobindo, the greatest seer of modern times, proclaimed the highest truth of human existence, the truth of a perfect form of man’s social living in which the individual soul rising into a higher consciousness will live in complete harmony with the collective soul of humanity and follow that ‘sunlit’ path of free participation by all in the service and adoration of the One in the Many.

This will be the spiritual foundation of the World-State of the future, as envisaged by Sri Aurobindo.

The Development of the Individual and the Collective

Spirituality is indeed the key-note of the Indian mind, says Sri Aurobindo.

“The master idea that has governed the life, culture, social ideas of the Indian people has been the seeking of man for his true spiritual self and the use of life life – subject to a necessary evolution first of his lower physical, vital and mental nature – as a frame and means for that discovery and for man’s ascent from the ignorant and natural into the spiritual existence.”

(CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 397)

* * *

As it was thought, and rightly, that for the attainment of this end, the one prerequisite is full freedom and utmost opportunities of self-development for the individual, so also it was believed that man’s collective living could grow into its perfect form only when it was smaller in size, having an individuality of its own, and was therefore better able to achieve its purpose and serve more effectively the larger collectivity of the country to which it belonged.

Every step in the forward march of man is first taken by the individual, the individual who is always the pioneer and the precursor. It is the labour of the individual that fructifies into what we call the progress of the race, for it is to him that the vision first comes as also the urge to give shape and form to it.

And what is true of the individual may also be true of the collectivity, but the latter cannot so easily move forward if it is larger in size and lacks compactness and inter-communion, as it happened in ancient times when communications were extremely inadequate to the purpose. Hence the existence then of smaller form of corporate living.

Every individual is more or less a particular type, and the more creative these individuals, the more markedly do they vary, one from the other. These very individuals having developed on the distinctive lines of their svabhāva[1], constitute the greatness and glory of the community to which they belong, and by the variety of their achievements immensely enrich and exalt its cultural life.

This is how they aid the general progress of the community, and therefore, its integration into a compact whole with an individuality of its own, composed of cultural, linguistic and geographical factors peculiar to the region inhabited by the community.

In the same way such groups can become free participants in the collective existence of a larger whole, having spiritual, cultural and political ideals which in their fundamentals are common to all the constituent groups, each of which by its distinctive characteristics contributes to the progress and well-being of the larger whole.

The central State in ancient India emerged out of this larger collective life both as a necessity and as a natural development. It was strengthened, among other factors, by the formation of representative assemblies for the deliberation of matters of common interest to the whole empire. And its growth had always been inspired by the great ideal of the race, the ideal of unity in diversity and diversity in unity.

Indeed, there can be no effective unity unless it evolves out of multiplicity. The many is the strength and contents of the one, even as the one is the truth and essence of the many. The autonomous and progressive units were thus the sustaining limbs of the body-politic or the central State, which stood for the oneness of the collective life of the race.

The Beginnings of the State in India

The beginnings of the State in India may be traced to the Vedic times when the unit of corporate existence starting with the family (griha or kula) enlarged itself through the village (grāma), the clan (vis), the people (jana) till it embraced the whole country (rāshtra).

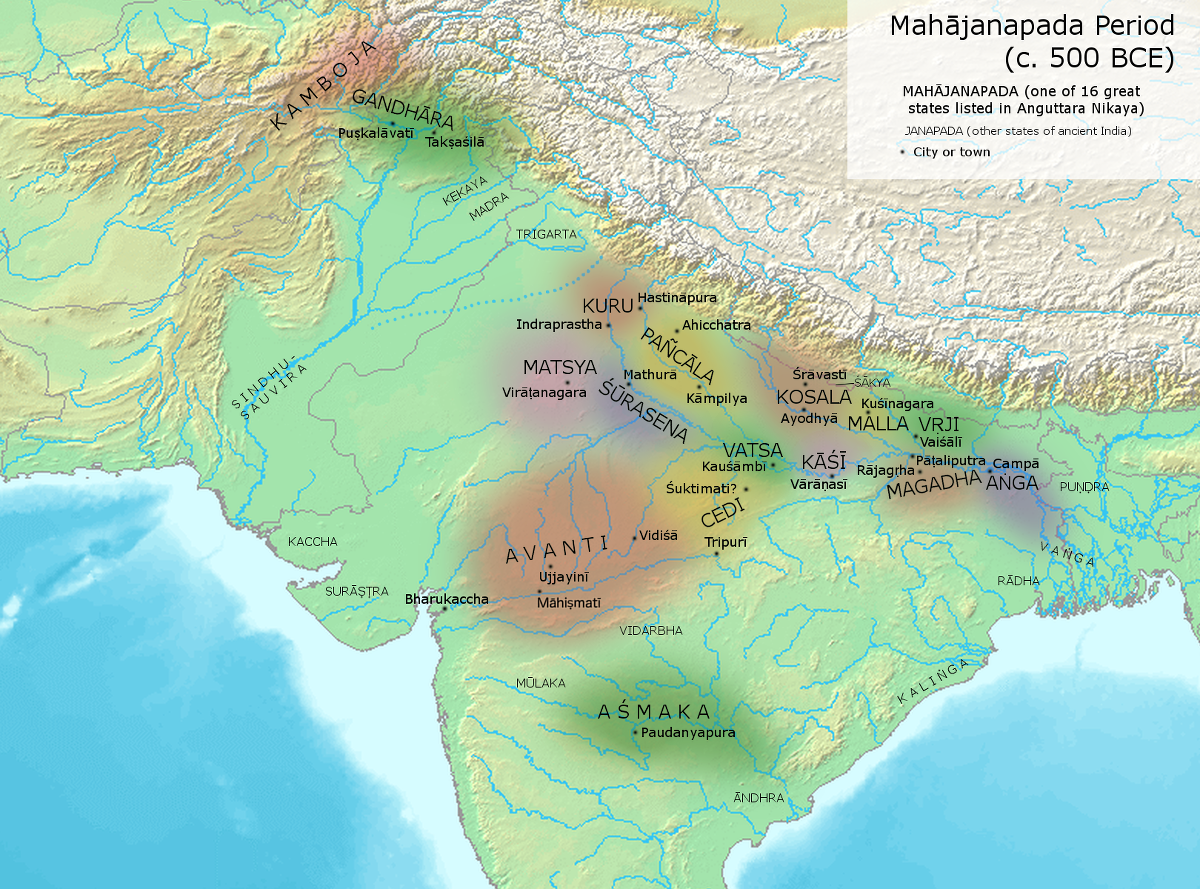

A region inhabited by a community was called a janapada which gradually developed into janapadarajya, a territorial State, and then into mahajanapadarajya, a larger territorial State, with the central authority vested either in a king or in a popular assembly, the sabhā and the samiti of the Vedic age, or in both, the latter always limiting the powers and prerogatives of the former.

It was this system which formed the framework and the mainspring of the mechanism of the State that evolved later in ancient India. And what is important about it is that notwithstanding the changes made at different epochs in the shape and character of these political structures, the village-unit ever remained the constant and vital factor as the very foundation for their growth and progress, thus showing the individualistic tendency of India’s political being.

It is with this village-unit that the Indian idea of democracy is always associated, since all its affairs, secular and religious, used to be looked after by the people’s assembly. The Panchayat system prevalent almost everywhere in India till today is derived from this. Will Durant, the eminent American thinker and historian, believes that the village community of ancient India is the prototype of all forms of self-government and democracy that have ever been evolved in various parts of the world.

The Greek Agora, Roman Comitia or German folk-moot, to which may be traced the democratic institutions of modern Europe, are said to be echoes of the Vedic samiti; but whereas no discussion was permitted in the former assemblies of Europe, the Vedic samiti, a sovereign assembly of the whole people, was a deliberative body where speeches were delivered and debates took place.

The Aim of the Community Life

The aim of the Vedic Aryans in these units of community life was to bring together the various parts of the country under the exalting influence of the Aryan culture. That they had a vision of India’s oneness is evident from the river-hymns of the Rig Veda; and their political endeavours indicate that they visualised a vast State representing the collective life of the people and seeking to establish the Aryan ideals as the ideals of the race.

The sovereignty of the Dharma as a guiding force in the life of the individual and the collectivity was a later and higher phase, when the social ideals of India had been already defined and systematised, and the units of community life had acquired a more definite shape.

Communal Freedom and Self-determination

The smaller communal units were formed and sustained by the village democracies and were linked with the larger territorial units that existed at the time. What really existed and was liberally encouraged was, says Sri Aurobindo,

the system of a very complex communal freedom and self-determination, each group unit of the community having its own natural existence and administering its own proper life and business, set off from the rest by a natural demarcation of its field and limits, but connected with the whole by well-understood relations, each a co-partner with the others in the powers and duties of the communal existence, executing its own laws and rules, administering within its own proper limits, joining with the others in the discussion and the regulation of matters of a mutual or common interest and represented in some way and to the degree of its importance in the general assemblies of the kingdom or empire.

(CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 405)

Many of these small states were of a republican character – another proof of their distinctive individuality – which gave them much of their strength and stability. The Buddha once said that if the republican character could be maintained in its purity and vigour, the state would remain ever invincible even against the attack of such a powerful emperor as Ajātasatru of Magadha.

During the Buddha’s time ten such republics existed in northern India, of which the Lichchavis of Vaisali were the most famous. There is evidence to show that the real strength of these republics lay not so much in their government as in the character of their people. Did not Plato say – “Like man, like state”, and “Governments vary as the characters of men vary.” Mention may be made here that many republican states existed in northern and central India till the fifth century of the present era.

Continued in Part 3

Have you read PART 1 of this essay?

Endnotes

[1] “own being”, “own becoming”; the principle of self-becoming; nature, real nature; essential nature and self-principle of being of each becoming; the pure quality of the spirit in its inherent power of conscious will and in its characteristic force of action; spiritual temperament, inborn nature, essential character.

Image credits

Cover image – Stupa no. 1, Sanchi: Source

Image 1: Source

Image 2: Source