Volume III, Issue 2

Author: K.R. Srinivasa Iyengar

Editor’s note: Our issue on the theme of progress could not have been complete without highlighting the Free Progress approach to education. The Mother indeed was an educationist of the future when she envisioned this and put into practice at Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education in Pondicherry.

We present selections from the book titled “On The Mother” by K. R. Srinivasa Iyengar (1994 edition published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, pp. 728-731). These summarise the key essentials of Free Progress system. For the ease of online reading, a few sub-headings are added by the editors.

In the early 1960s the Centre of Education was to undergo the beginnings of a revolution in the pupils’ motivation, in curricular structuring and in teaching techniques.

More than once during the nineteen-fifties, the Mother had expressed her deep dissatisfaction even with the best that was being done at the Centre of Education, and of course she knew that what passed for education in the outside world was hardly worth the name. But it was not enough for the Centre of Education to do just a little better than what others did badly elsewhere. A bolder attitude or strategy was called for in consonance with Sri Aurobindo’s vision of the future.

Once, indeed, she said with a sweeping glance at the educational scene and a penetrating look into the future:

When I look at the education everywhere, I feel like the Yogi who was told to sit and meditate in front of a wall. I find myself facing a wall. It is a greyish wall, with some streaks of blue running across it—these are the efforts of the teachers to do something worthwhile—but everything goes on superficially and behind it all is like this wall here . . . It is hard and impenetrable, it shuts out the true light. There is no door—one can’t enter through it and pass into that light. . .

I have the intention of taking in hand the problem of education. I am preparing myself for it. It may take two years. But. . . when I intervene and remould things, it may seem like a cyclone. People may feel that they can no longer stand on their legs! So many matters will get upset. There will be all-round bewilderment at first. But, as a result of the cyclone, the wall will break down and the true light burst in.

~ CWM, Vol. 12, pp. 145-146

No Sharp Distinction between Study and Relaxation

From the very inception of the Ashram School in December 1943, and during the two decades following, the Mother refused to make any sharp distinction between study and relaxation. All study was to be undertaken without external pressure; in other words, in a spirit of adventure. And all relaxation had its educative value. One might almost say that life at the Centre of Education was organised — or, rather, organised itself, in the Mother’s own words, “on a routine of almost constant relaxation”.

Any imposition of rigid routine from without must smack of tyranny, and children especially — like buds and blossoms — might wither all too soon and lose their native freshness and honey under the glare of such discipline. “A child ought to stop being naughty,” said the Mother, “because he learns to be ashamed of being naughty, not because he is afraid of punishment”; and, after, all, what was fear but “a degradation of consciousness”? After learning to be ashamed of being naughty, the child could be expected to “make further progress and learn the joy of being good”. (CWM, Vol. 12, p. 362)

Education to Help Bring Forward the Inner Law of Things

There was an inner law, an inmost truth of things, which prescribed the norms of behaviour. And the problem of education was to help this law, this truth , to come out to the forefront of its own accord. In order to avoid the tyranny of an imposed discipline as well as the chaos of unbridled thought and action, one had to cultivate right discrimination leading to self-discipline, which was but another word for self-mastery.

Pupils and teachers were alike heirs to infinite liberty. But to follow that path of liberty one must have the consciousness of the Divine Presence in oneself and know that the Divine was present in all others as well. Once this was realised, there would be no danger that liberty might be mistaken for licence or freedom for unsocial or outrageous behaviour.

Freedom, the Oxygen of Whole Scheme of Things

This stress on freedom was not, however, confined to any one aspect of life at the Centre of Education, for freedom indeed was the very oxygen of the whole scheme of things, except that it needs must be held in leash by the paramountcy of Truth, by the innermost Law of things.

The new thrust given to education at the Centre was the sovereign dynamic of Free Progress. Pupils were now free to choose what subjects they liked, cultivate intensely what areas they chose. And they were free also to take or not to take examinations even in the subjects of their choice.

Although the different stages of education were to be graded as before – pre-primary, primary, secondary, higher secondary, and tertiary or collegiate – this was to be no steel-frame classification. For pupils would be free to take some subjects at one level and others at other levels. In the Higher Courses there were the traditional faculties (Arts, Science, Engineering, etc.), but again pupils were free to opt for courses from more than one faculty.

Joyous Adventure of Self-discovery and World-discovery

The new atmosphere of almost unlimited freedom had as a rule a bracing effect upon the pupils. Not only more was usually achieved in less time, but all was accomplished as a joyous adventure of self-discovery and world-discovery.

When the question “Why are diplomas and certificates not given to the students of the Centre of Education?” was put to the Mother in 1960, she had answered that mankind was afflicted with the malady of chronic utilitarianism. Everything was judged from the monetary angle alone, even children were made to hanker after visible success – anyhow, somehow – at an age when “they should be dreaming of beauty, greatness and perfection.”

And so it was necessary to place before the children who were being trained for the tasks and challenges, not of dead yesterday or dying today, but those of the unborn tomorrow, a very different ideal altogether:

To learn for the sake of knowledge, to study in order to know the secrets of Nature and life, to educate oneself in order to grow in consciousness, to discipline oneself in order to become master of oneself, to overcome one’s weaknesses, incapacities and ignorance, to prepare oneself to advance in life towards a goal that is nobler and vaster, more generous and more true. . .

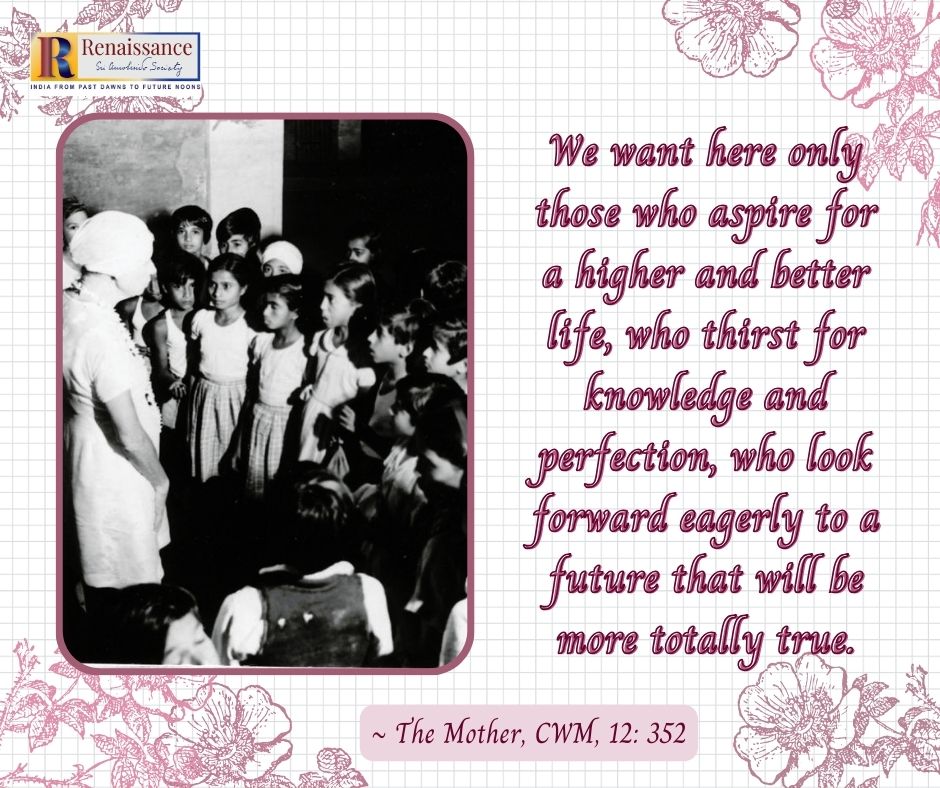

We want here only those who aspire for a higher and better life, who thirst for knowledge and perfection, who look forward eagerly to a future that will be more totally true.

~ CWM, Vol. 12, pp. 351-352

Watch the Video:

Three Central Aims of Education

The academic courses were not to be stereotyped as of old so as to prepare the pupils to take their vulnerable places in the rat-race of the outside world. The aim should rather be to usher in a new race ready to face and shape the future, and not just to achieve the annual turnout of so many clerks and accountants and technicians of all sorts.

In short, the emphasis would be more than ever on integral development, the body, mind and the soul in a concert of striving and moving towards a new symphony of aspiration and achievement.

How Free was Free Progress System?

As regards the Free Progress system itself, it was far easier to misunderstand or misrepresent it than to grasp all its implications and possibilities and set them forth convincingly in merely logical categories. How exactly free was this Free Progress system? The discipline of freedom could be far more exacting than the rule of mechanical regulation.

In a large sense, the ‘system’ went back to the hoary example of Satyakama Jabala who was sent by his Guru after initiation to the forest, with the strange directive that when the four hundred lean cows became one thousand, the pupil might return. But Satyakama was as keen and observant as he was truthful. And he had an insatiable thirst for knowledge. So he observed things, kept his eyes and ears open, communed with the world around him – till ultimately he knew the Truth of all things.

At the Centre of Education too, the pupil was expected to rely chiefly on his native faculties, and above all on his soul’s intimation and illuminations.

Progress Guided by the Soul

Free Progress as the Mother put it succinctly, is “a progress guided by the soul and not subjected to habits, conventions or preconceived ideas”. (CWM, Vol. 12, p. 171)

Nature thrives on infinite variety. And no two children are exactly alike in their endowments or inclinations, their abilities or aspirations. The paradox of the human situation is the teaming together of physical, vital and intellectual diversity and the deeper unity of the soul or spirit.

Free Progress was expected to ensure that each child retained his educational autonomy, discovering his own special aptitudes and identifying the desired goals, determining his own directions and pace of progress, and working out with diligence, dedication and a sense of adventure and responsibility his own place and role in the drama of divine evolution.

Role of the Teacher in Free Progress

Free Progress, even when most free and progressive, was not however meant to eliminate the teacher altogether. On the contrary, a greater – not a lesser – responsibility would lie on him than in the traditional system. But the teacher would now need to change his style of functioning, adopting with conviction a new attitude towards his pupils and towards the aim of education itself.

Knowledge is a whole Himalaya that has piled up during the millennia of ceaseless human inquiry, speculation and experimentation. And without the teacher’s guidance the child may feel rather lost while journeying alone. The teacher could help the pupil to feel at home in the House of Knowledge, to look up things for himself and to avoid needless wastage of effort.

More especially, the teacher could help to create for the pupil an environment or atmosphere of affection that brings out the best in him, sustains in him a steady attitude of inquiry and enables him in course of time to “find his deeper self, the real psychic entity within”.

Nor could formal or classroom teaching or lecturing be wholly dispensed with. The cardinal principle, however, was that whatever became a mere routine was an enemy of creative life and of true education. And whatever affirmed and advanced the dynamism of life, the need for adventure and the endless possibility of progress through controlled experimentation was education’s ally.

The Free Progress system, as the Mother visualised it, was thus no rigid lifeless body of procedures, no high sounding dogma, no structure of theory, but was something as large and as complex and as evolutionary as life itself.

It was not a key that shut pupil and teacher in a prison-house. It was rather the key that opened the gates leading pupils and teachers as fellow-seekers and fellow-adventurers to God’s garden of life and knowledge and infinite possibility.

Also watch:

India’s National Development in the Light of

Sri Aurobindo’s Educational Philosophy

~ Graphic Design: Beloo Mehra and Biswajita Mohapatra