Editor’s Note: Kireet joshi in his book ‘Glimpses of Vedic Literature‘ summarises the essence of Bhriguvalli from Taittiriya Upanishad and emphasises that Food or Matter is also a manifestation of the Divine which should not be rejected but instead be mastered. The following text is excerpted from 2006 edition, pp. 133-137. We have made a few minor formatting revisions for the purpose of this digital presentation.

🌸

Five planes of manifestation of the Eternal

THERE are five sheaths of our being, beginning with the material and culminating in the blissful. This is the main substance of the Taittiriya Upanishad’s section Brahmavalli, . .

Corresponding to these five sheaths, there are five cosmic planes of the manifestation of the Eternal. This is the main substance of Bhriguvalli, which is the last section of the Taittiriya Upanishad. It consists of a dialogue between Bhrigu, Varuna’s son, with his father.

Let us see how the dialogue begins. It will also show how the Upanishadic teachers used to teach their pupils,— not by giving discourses, but by suggesting a few key words and leaving the pupils to meditate thereon and to explore by thought and askesis.

“Bhrigu, Varuna’s son, came unto his father, Varuna and said, ‘Lord, teach me the Eternal.’

And his father declared it unto him thus, ‘Food and Prana and Eye and Ear and Mind—even these.’

Verily, he said unto him, ‘Seek thou to know that from which these creatures are born, whereby being born they live and to which they go hence and enter again; for that is the Eternal.’ And Bhrigu concentrated himself in thought and by the askesis of his brooding.”

There is, we might say, a psychological law of development. According to this law, there are two approaches to the seeking of the Highest. The first is synthetic, which is spontaneous in the intuitive consciousness.

In this consciousness, there is inherent harmony, stability and delight. But often this consciousness in our infancy is not self-conscious. It operates rhythmically in our mind and there is no questioning. The being is luminously self-absorbed in a state of harmony and the play of life is guided spontaneously by that harmony. But in the course of evolution of our mind, there is the inevitable urge for self-consciousness. And this urge tends in mental consciousness to manifest by breaking the original spontaneous harmony.

Once this harmony is broken, there comes into operation the second law, the law of ascending from below upwards, which builds up in our psychology knowledge of all terms of existence, one by one, one adding upon another, from the lowest to the highest.

This law operates not by intuitive consciousness of the totality, but by concentration and by askesis, a process of laborious ascent. There is in this process of development a questioning and strenuous gathering of knowledge step by step.

The teacher, aware of this process which was valid for the development of Bhrigu, places before the pupil the ascending terms of existence. Food, that is Matter, Prana, that is Life and Eye and Ear, which represent the senses, the first appearances of the operation of consciousness, and next the Mind. The teacher then asks the pupil to find out which of them, if any, is more fundamental and therefore the Eternal.

Read:

Refining the Sense of Taste with No Attachment to Food

The pupil is thus given a programme of search. Evidently, the teacher does not want to give the answer, but wants the pupil to find out the answer through his own effort. The teacher has only given a riddle and a hint. The rest is for the pupil to work out.

Food is the Eternal

The first answer that Bhrigu arrived at was that Food, that is Matter, is the Eternal. Indeed, matter is so pervasive and so directly seizeable by our senses that the easiest position to take for the sense-bound consciousness is that Matter is the only Reality.

As Bhrigu declares to his teacher:

“From food alone, it appears, are these creatures born and being born they live by food, and into food they depart and enter again.”

“annam brahma“—Matter is Brahman,—this is the first formulation of thought in its ascent. This is materialism.

But Bhrigu did not stop here. He came back to his father and said, “Lord, teach me the Eternal.” But the teacher gave only an enigmatic answer: “By askesis do thou seek to know the Eternal, for askesis is the Eternal.”

Bhrigu went back to concentrate in thought and by energy of his brooding he ascended to the next step in the hierarchy of planes of Existence. He discovered that Prana, Life, is the Eternal. This is the position of vitalism, which finds that the whole world is pulsation of Life-Force, as is declared, in our modern times, by the French philosopher, Bergson.

But Bhrigu did not stop here. He made a further ascent. And he declared that mind is the Eternal. In our times, philosophies which regard mind to be the original principle of existence are called variations of idealism, since they all regard Idea to be the formative and creative principle of universe.

Divine Materialism

In the history of thought, most of the philosophies have moved between materialism, vitalism and idealism. Certain religious or spiritual philosophies have gone one step farther and have conceived of the Spirit as the Eternal. But often Spirit is conceived as static and not dynamic. Spirit, therefore, is regarded not as a creative principle, but only as a state of ultimate peace and release from all dynamic creativity.

But the Veda and the Upanishads had discovered between the Spirit and the world of Matter, besides Life and Mind, an intermediate creative principle, which they called “vijnana“‘, comprehensive knowledge (as distinguished from Mind, which is the principle of piecemeal, analytical and partial knowledge.)

Therefore, we find Bhrigu making a further ascent from the Mind and discovering Vijnana. As the Upanishad states: “He knew vijnana (knowledge) for the Eternal.” (vijnanam brahma iti vyajanat.)

But even beyond vijnana, there is a greater and higher principle of creativity to which Bhrigu ascended and came to know that Bliss is the Eternal. This is how the Taittiriya Upanishad describes the discovery of Bhrigu:

“He knew Bliss for the Eternal. For from Bliss alone, it appears, are these creatures born and being born they live by Bliss and to Bliss they go hence and return. This is the lore of Bhrigu, the lore of Varuna. He who hath his firm base in the highest heaven, he who knows and gets his firm base, he becomes the master of food and its eater, great in progeny, great in cattle, great in the splendour of holiness, great in glory.“

Discovery of the ascending series of existence does not end in annulling the lower principles of existence. Discovery of Bliss is not the rejection of Matter, as the Upanishad declares:

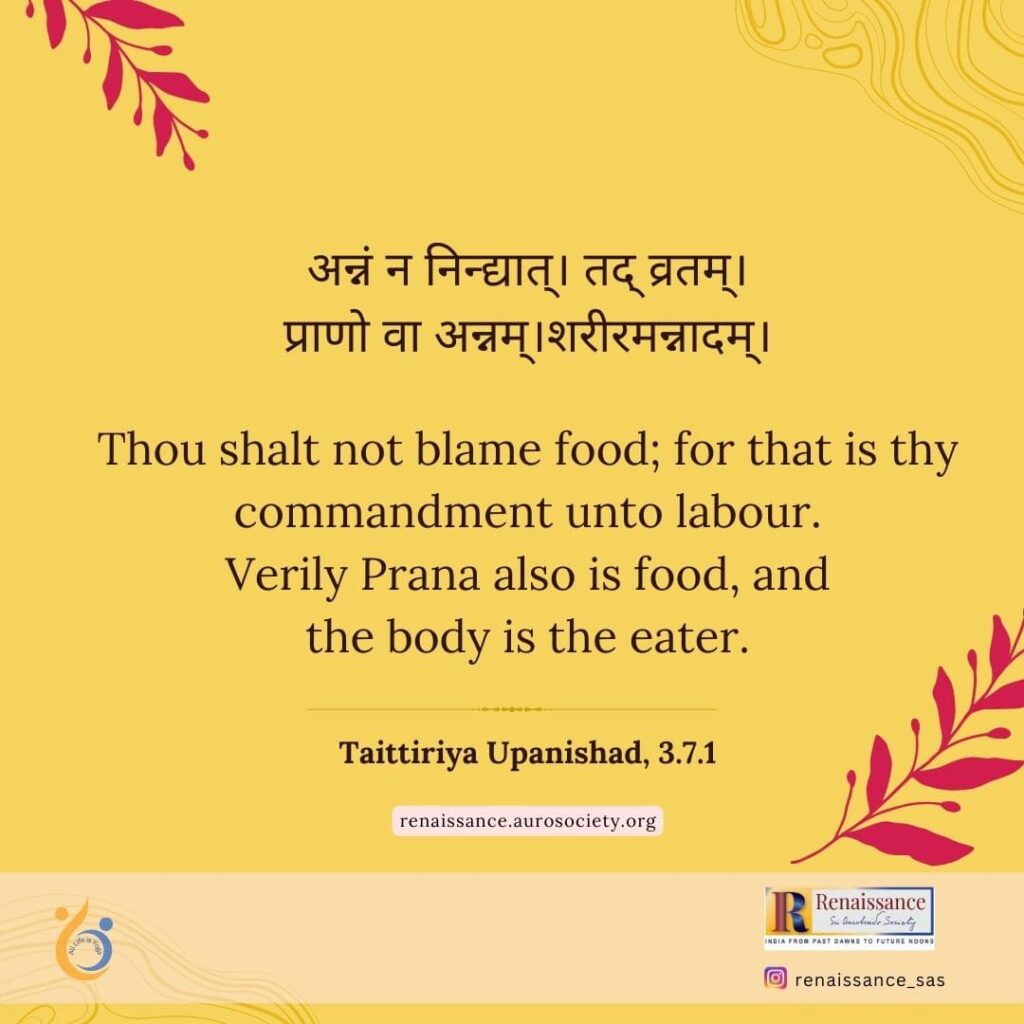

“Thou shalt not reject food; for that too is the vow of thy labour.“

It may, indeed, be said that the Taittiriya Upanishad is the foundation of the philosophy of total affirmation and synthesis, —synthesis of the Divine Bliss and Matter, what may properly be called Divine Materialism.

🌸🌸🌸

Also Read:

Cultivating a Yogic Attitude toward Food

~ Design: Raamkumar