Volume VI, Issue 4

Compiled by Beloo Mehra

Editor’s Note: We feature selections from the book Indian Sculpture and Iconography: Forms and Measurements (2002). The book was published by Sri Aurobindo Society in collaboration with Vaastu Vedic Research Foundation, Chennai. For the ease of online reading, we have made a few formatting revisions including adding a few headings.

Different Types of Divine Forms and Images

In the shilpa shastra, the state of existence of the Primary Energy and its subsequent movement into the manifestation of phenomena are described in a unique manner. They say the tangible universe contains within it the primary substance which is beyond sensory perception. It cannot be comprehended by thought or expressed through words. It exists as the energy of sound and light, and permeates all beings. Called Vastu or Vastu Brahman, it is the source of all manifestation, growth, movement, and containment. The ancient shilpi-rishis, fully aware of this substance, have classified its revelation into three states:

| Tamil | Sanskrit | English |

| Aruvam | Avyaktam or Nishkalam | Amorphic |

| Aruvuruvam | Vyaktavyaktam or Sakala-nishkalam | Morpho-amorphic |

| Uruvam | Vyaktam or Sakalam | Morphic |

Aruvam or Nishkalam

Aruvam or Nishkalam is the abstract state of formlessness, wherein the different parts of the body and other physical attributes are undefined and, hence, represented in an amorphous state. The lingam, which does not possess human bodily features and is only an abstract symbol, is an example of this. The state of aruvam is said to be all pervasive and luminous and, hence, is known as Light or Absolute Light. Because of its luminous nature, the lingam is called the Jyotir Lingam.

Lingam at Virupaksha temple, Pattadakal

Source: matriwords.com

Aruvuruvam or Sakala-nishkalam

In Aruvuruvam or Sakala-nishkalam, the parts of the body and other physical features are partly defined and partly suspended in an amorphous state. The phase represents the qualitative state of existence, where the physical features of the human body are not fully represented, though the attributes are implied. The Mukha Lingam is described in the texts as an example of this kind of image.

Uruvam or Sakalam

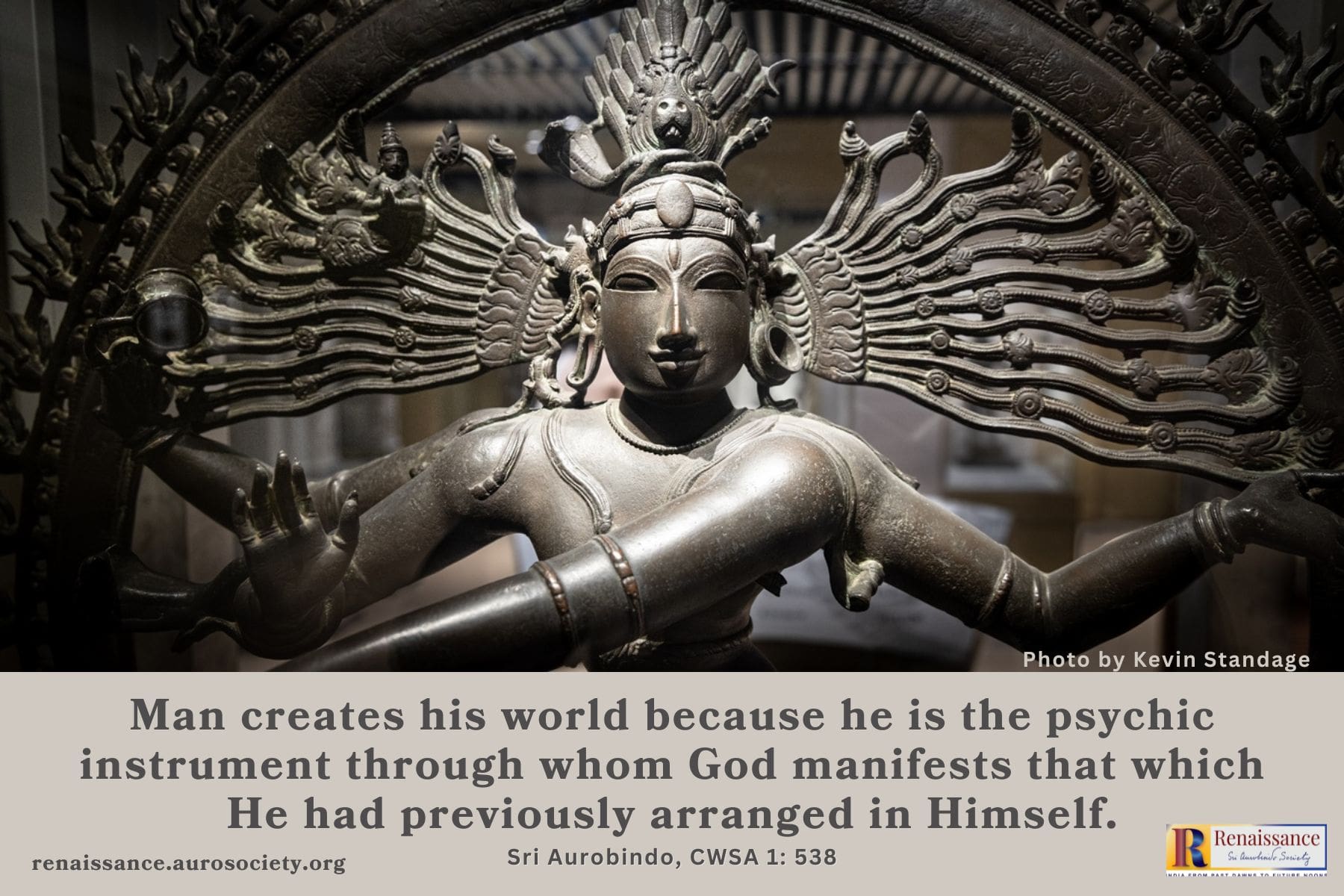

Uruvam or Sakalam is the form where the body, with all its physical features, is well defined and represented in a perceivable, tangible manner. Examples of this type are the images of Chandrasekhara and Vishnu.

Vishnu, 10th century, Tamil Nadu

Source: wikicommons

***

Man’s inner vision of the divine one, his intuitive understanding of the great truths, and his experiences of reality can be seen to reflect these manifestations of the primary substance. Unlike the schools of ‘realism’ where the perceived object is faithfully represented in an art form, the traditional shilpa style requires the artist to respond inwardly to the stimulus. And from this inner response, create the image with all the artistic skills at his command. The formlessness is expressed in terms of bodily features signifying universal rhythm and balance. Thus, the intangible takes concrete and real form. The shilpa texts have, therefore, specified these forms and images as being suitable for worship.

The texts also state that it is not appropriate to worship images fashioned in the proportions of a human body, though they may be in accordance with the natural order. This is because the human body is subject to change and decay in time. But the image produced by the application of the grammar set out in the mana lakshanam (iconometry) is eternal, and, the hence, untouched by time.

In the sculptural tradition, the grammar is very important and is considered to be the process through which the Brahman manifests itself. It is thus of vital importance that the sculptors in the traditional mode should fully comprehend the grammar and order of this system. Only then, will they be able to design with clarity.

Sculptor’s Thorough Knowledge

Whether an image is created for worship or as an object of art, the sculptor should have a thorough knowledge of the following:

- The various forms and images

- The different raw materials utilised for image-making

- Qualities and descriptions of the images

- Dimensions of images – Ayadi manam (Derivation of beneficial measures)

- Rhythms and proportions – Tala manam

- The six basic measurements and plumb lines

- Physical resemblance to natural objects (semblance of features)

- Hand poses or gestures

- Body flexion

- Dance postures

- Seated poses

- Costumes and ornaments

- Symbols and motifs

- Imaginative features

- Colour

- Evocation, expression

Classification of Images

There are three broad classification of images:

- Chitram – sculpture in the round

- Chitradham – sculpture in bold relief

- Chitrabhasam – representation on a plane surface (painting)

Chitram is the term employed for sculptures presented in the full, in three-dimensional form. Images made of metal are good examples of this type. Chitradham describes bas reliefs, which have only their frontal part carved in full detail, leaving the rear portion flat. The figures are generally carved on the rock-face or moulded on the wall with brick and mortar or other materials to create a deep relief. Representation of futures on flat planes like walls, paper, canvas or boards which do not have any projections is known as chitrabhasam. This art form can be either as line drawings on coloured paintings.

Because the impact of the image on the devotee is the most in chitram, the texts say that the benefit derived by the worshipper is maximum in this representation, medium in the case of chitradham or the image in relief, and minimal in the case of chitrabhasam or pictorial depiction.

Vishnu, Badami cave 3

Source: matriwords.com

Classification Based on Mobility

Images can also be classified into three types, based on their mobility.

Achala (immobile): Sculptures are achala when they cannot, or should not, be shifted from their place of installation. Those made of rock, grit, mortar or earth are examples of this type.

Chala (mobile): Images capable of being moved, or intended to be moved — such as those made of granite, wood, minerals and precious stones are described as chala.

Chalachala (mobile/immobile): Those images that are capable of being moved, but are installed immovably in a fixed spot, are known as chalachala. Images fashioned out of granite or wood that have been installed in a particular place are good examples.

Seated Buddha, circa 475, Sarnath Museum

Source: Wikicommons

Classification Based on the Attitudes and Expressions

Yet another three-fold classification is based on the attitudes and expressions of the images.

- Sattvika, calm, tranquil, ethereal, luminous

- Rajasa, energetic, heroic, movile

- Tamasa, aggressive, violent, destructive

The sattvika image is that which is presented in a yogic stance, wearing a tranquil expression, with the postures (mudra) of the hands dispelling fear and offering benediction to the worshipper. The images of Dakshinamurti, Chandrasekhara, and Srinivsa are typical examples of the sattvika form.

The rajasa image is either standing or mounted on a vehicle, is richly adorned with various ornaments, with the hands again held in the postures of removing fear (abhaya) and granting prayers (varada). The form of Subrahmanya belongs to the rajasic type.

The tamasa image — (that of Mahishasuramanrdhini being a good example) is armed with various implements of war and is perceived to be destroying evil forces. It has a fearsome expression on its face and its posture reflects great pleasure in acts of destruction.

We move into the nest set of classifications based on the proportions of the images. An image which is of seven tala is called the vamana (dwarf) type, that of eight tala belongs to the manusha (human) category, and one of nine tala is of the deivika (divine) class.

To Give Form to the Intangible and the Abstract

The sacred precinct of the temple is the divine being and should be praised as the form of the Lord.

~ Shilparatnam, Chapter 16, verse 24

Sculptural images which have been fashioned for worship should not only be created with imaginative skill, but should reflect the specific philosophical and religious character of the belief system that they pertain to. They should be suitable for worship as defined by that particular belief. And they should also be composed within the exacting grammatical constraints set out in the shilpa shastra.

To be able to meet these requirements, it is essential that the shilpi should have integrated within himself the many branches of knowledge from which such creations are possible. The shilpi should not only have a comprehensive grounding in the shilpa shastra, excellent technical skills, and a great appreciation of art forms; it is also imperative that he has extensive knowledge and understanding of philosophies and belief systems, a flawless personal lifestyle and is deeply religious and devout.

To give form to the intangible and the abstract is not easy, particularly when they pertain to feelings and to qualities which are amorphous characteristics of the Divine. To give shape to such incomprehensible, subtle qualities and to define them in concrete, material forms is a very difficult task. It requires the artist to possess energy similar in quality to that of a yogi, which is contained in unswerving stillness. Only from such a state can creativity emerge.

Forms of the Formless as Experienced by the Yogis

Even though the profound philosophical traditions do not subscribe to the Divine Being having one form or one name, religious leaders, philosophers and thinkers have described and spoken of Him in the many belief systems. The form of the Ultimate Being or Muzhu Mudal Porul is incomprehensible and beyond thought. But yogis and sages have experienced His beauty through their bhakti and through extraordinary powers of vision. And from these experiences they have developed some simple methods by which ordinary mortals like us may also come close to His infinite sublimity.

The visionaries and teachers of the vaastu tradition have set out clearly their experiences and insights regarding the creation of the universe, its outer manifestations, its growth and its dissolution.

Agama Shastra

The agama shastra have explained the secrets of the universe and the Divine Being who is responsible for it. They have also clarified the natural characteristics of life forms. Further, the agama texts have confidently defined the formless and given Him a physical form, endowed with characteristics the One who is beyond qualities, and called upon Him who is nameless, with various names. Such is the strength of the agama that they have moved and mobilised the One who is contained in stillness and have brought Him down to inhabit the earth.

Even though their basic methodology is similar, the many beliefs and religious systems have metamorphosed the Divine Being in different forms and have described Him in many different ways. Each of these beliefs has given special physical attributes to their gods — as a three-eyed one with unruly hair, clothed in deer skin; or as blue-skinned, with a crown on His head and conch and shell in hand; or with an elephant head; or with six heads; or as the divine mother. There are infinite variations to the form of God.

Divine One and His Many Wonders

The agama shastra not only speak of the Divine One and describe His many wonders, but also invest Him with innumerable glorious forms. In short, they create a world of divine forms and manifestations. To bring the Divine Being closer to people and hence make Him a part of their lives, they have also given Him human forms.

Through deep meditation and intense love for Him, we are able to come in touch with the Divine Being. The agama speak of Him as the source of our spirit, the instrument of our action, as our protector and inspired leader. Some of the agama maintain that images we worship are invested the power of His being; and they also go one step further to say that sacred image itself is the Divine Being (archavatara).

Generally, the images we worship symbolise the divine characteristics. Moreover, they also serve to explain the various philosophical and religious systems of thought. Shaivam, Vaishavanam, Shatam, Ganapatyam, Kaumaram and Sauram are the 6 main systems of belief which subscribe to image worship. Shaivam speaks of Shiva as the UItimate Being, Vaishnavna believes in Vishnu, Shaktam in Shakti (Divine Mother), Ganapatyam in Ganapaty, Kaumaram in Kumara (Muruga), and Sauram in Survya. Shaktam, Ganapatyam, Kaumaram and Sauram are all a part of Shaivam. Hence the two main religious systems are Shaivam and Vaishnavam.

The texts which clarify and explain the methodology of worship are called agama shastra. The word agama means the traditional mode of understanding and explaining the state of the Divine Being. The agama shastra explain the various ways in which the individual spirit of man lives and enjoys its earthly life, then releases itself from the bondage of desire and enters into the blissful state of integration with the Primary Being.

Also read:

The Origin of Image Worship in India

~ Design: Beloo Mehra