Volume VI, Issue 6

Author: Sri Aurobindo

Editor’s Note: Sri Aurobindo emphasises that to truly ‘see‘ an Indian painting, we have to fully grasp its intention and aim, namely, the psychic suggestion or feeling that the artist is trying to express through form, line and colour. Appreciating the artist’s technique is not sufficient. Nor is it enough if we can understand the fervour of religious feeling which may be the subject of the painting.

We must be capable of feeling the “spiritual intention served by the technique, the psychic significance of line and colour, the greater thing of which the religious emotion is the result”. Only then a true rasik of Indian art would be able to identify with the artist’s whole purpose.

We feature two examples through which Sri Aurobindo himself teaches us how to ‘see’ an Indian painting. He has given deeply sensitive and profound descriptions of two paintings — one from Ajanta, and the other from Bengali school of painting. Reading these passages serves as great education in Art Appreciation, the Indian Way, for any lover of Indian art.

Before Sri Aurobindo’s description of all that he ‘sees’ in the painting, we have given a general background of the narrative that is depicted in each of the paintings.

Also read 2-part article from archives:

An Intuitive and Spiritual Eye to Appreciate Indian Art

‘Yashodhara and Rahul meet the Buddha’

Ajanta, Cave 17

General Background of the Painting

This is one of the most enchanting murals at Ajanta. The story goes that after his enlightenment, Buddha, the great renunciate, returned to Kapilvastu after leaving the town seven years earlier. Buddha, prince Siddhartha at that time, had left in the middle of the night leaving behind his wife Yasodhara who was sound asleep. Yashodhara now took their son, prince Rahula, to the place where Buddha, the enlightened, was preaching. She told her son that when he meets Buddha he should ask for his inheritance.

Rahula walked through the assembly to stand before the Buddha. And the first thing he said to Buddha was, “How pleasant is your shadow, O Bhikshu”. They have a brief conversation and Rahula demands his inheritance from his father, the Buddha.

Buddha had abandoned the kingdom and the worldly life. So he gave his son the most precious knowledge as inheritance, ‘the Dharma’. Rahula attained enlightenment at the age of eighteen.

How Sri Aurobindo ‘Sees’ the Painting

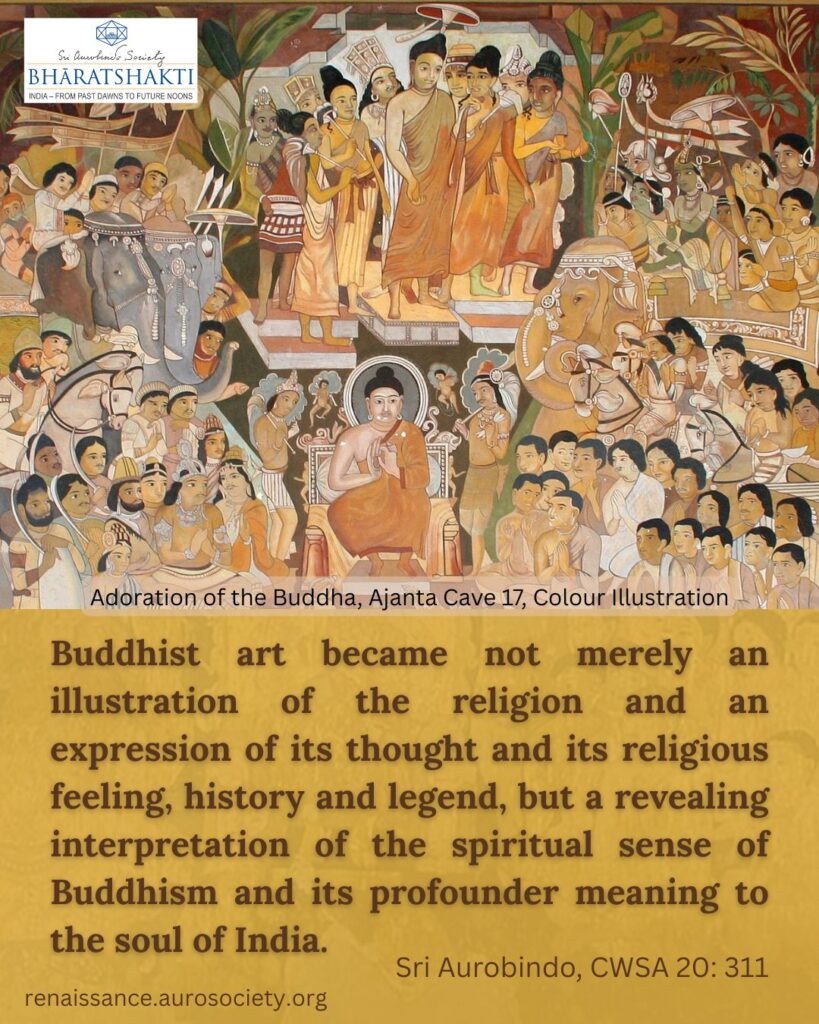

If we look long, for an example, at the adoration group of the mother and child before the Buddha, one of the most profound, tender and noble of the Ajanta masterpieces, we shall find that the impression of intense religious feeling of adoration there is only the most outward general touch in the ensemble of the emotion.

That which it deepens to is the turning of the soul of humanity in love to the benignant and calm Ineffable which has made itself sensible and human to us in the universal compassion of the Buddha, and the motive of the soul moment the painting interprets is the dedication of the awakening mind of the child, the coming younger humanity, to that in which already the soul of the mother has learned to find and fix its spiritual joy.

The eyes, brows, lips, face, poise of the head of the woman are filled with this spiritual emotion which is a continued memory and possession of the psychical release, the steady settled calm of the heart’s experience filled with an ineffable tenderness, the familiar depths which are yet moved with the wonder and always farther appeal of something that is infinite, the body and other limbs are grave masses of this emotion and in their poise a basic embodiment of it, while the hands prolong it in the dedicative putting forward of her child to meet the Eternal.

READ:

Sri Aurobindo on the Art of Painting in India

This contact of the human and eternal is repeated in the smaller figure with a subtly and strongly indicated variation, the glad and childlike smile of awakening which promises but not yet possesses the depths that are to come, the hands disposed to receive and keep, the body in its looser curves and waves harmonising with that significance. The two have forgotten themselves and seem almost to forget or confound each other in that which they adore and contemplate, and yet the dedicating hands unite mother and child in the common act and feeling by their simultaneous gesture of maternal possession and spiritual giving.

The two figures have at each point the same rhythm, but with a significant difference. The simplicity in the greatness and power, the fullness of expression gained by reserve and suppression and concentration which we find here is the perfect method of the classical art of India. And by this perfection Buddhist art became not merely an illustration of the religion and an expression of its thought and its religious feeling, history and legend, but a revealing interpretation of the spiritual sense of Buddhism and its profounder meaning to the soul of India.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, pp. 309-311

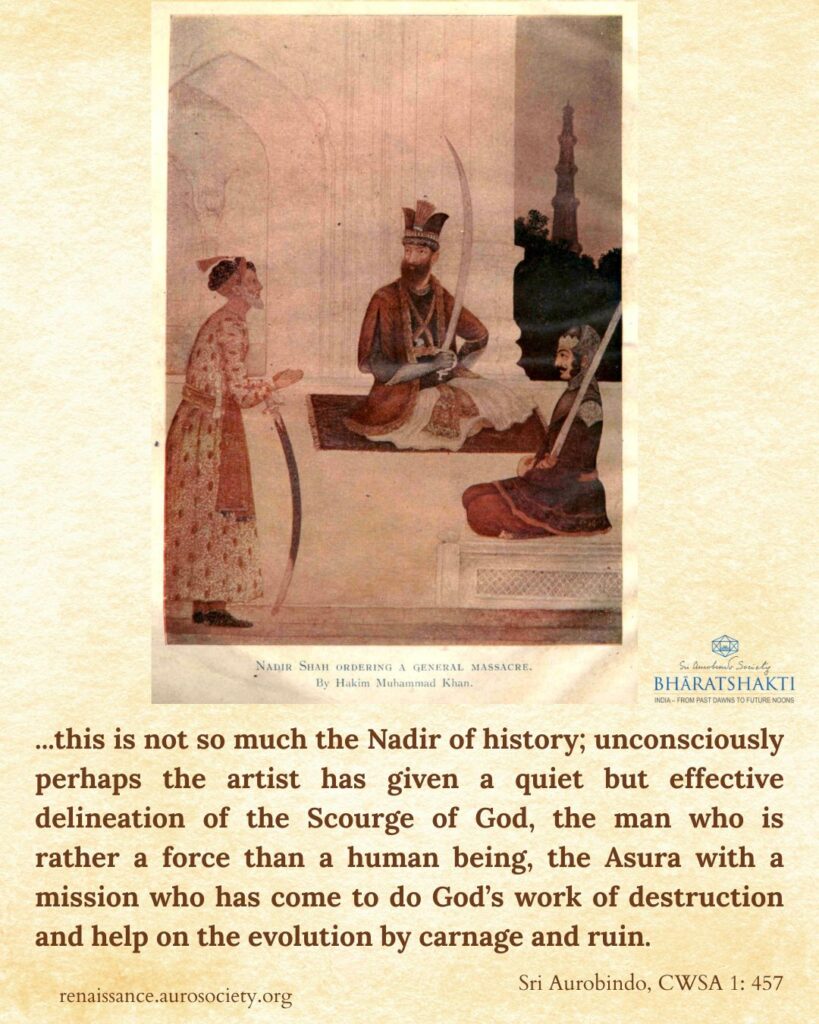

‘Nadir Shah Ordering a General Massacre’

Painting by Hakim Muhammad Khan

General Background of the Painting

Nadir Shah (1688-1747), Shah of Iran from 1736 to 1747 invaded India in 1739. He advanced up to Delhi and ordered a plunder and massacre of its citizens. The painting by Hakim Muhammad Khan depicts a historical event which involved a general slaughter of the city’s inhabitants following an uprising against Nadir Shah’s troops. The painting captures the scene when Nadir Shah, in full armor, rode out from the Red Fort and gave the order for the massacre.

The massacre resulted in the death of an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 people. Nadir Shah extracted a huge fine from the people of Delhi and seized the imperial treasury, including the Peacock Throne. The event is remembered as a devastating blow to the Mughal Empire, which was already facing decline.

How Sri Aurobindo ‘Sees’ the Painting

The picture… by Mahomed Hakim Khan, a student of the Government School of Art, Calcutta,… represents Nadir Shah ordering a general massacre. It is not one of those pictures salient and imposing which leap at once at the eye and hold it. A first glance only shows three figures almost conventionally Indian in poses which also seem conventional.

But as one looks again and again the soul of the picture begins suddenly to emerge, and one realises with a start of surprise that one is in the presence of a work of genius. The reason for this lies in the extraordinary restraint and simplicity which conceals the artist’s strength and subtlety.

The whole spirit and conception is Indian and it would be difficult to detect in the composition a single trace of foreign influence. The grace and perfection of the design and the distinctness and vigour of form which support it are not European; it is the Saracenic sweetness and grace, the old Vedantic massiveness and power transformed by some new nameless element of harmony into something original and yet Indian.

Notice the Details

The careful and minute detail in the minutiae of the dresses, of the armour of the warrior seated on the right, of the flickering lines of the pillar on the left are inherited from an intellectual ancestry whose daily vision was accustomed to the rich decoration of Agra and Fatehpur Sikri or to the fullness and crowded detail which informed the massive work of the old Vedantic artists and builders, Hindu, Jain and Buddhist.

Another peculiarity is the fixity and stillness which, in spite of the Titanic life and promise of motion in the figure of Nadir, pervade the picture.

A certain stiffness of design marks much of the old Hindu art, a stiffness courted by the artists perhaps in order that no insistence of material life in the figures might distract attention from the expression of the spirit within which was their main object. By some inspiration of genius the artist has transformed this conventional stiffness into a hint of rigidity which almost suggests the lines of stone.

This stillness adds immensely to the effect of the picture. The petrified inaction of the three human beings contrasted with the expression of the faces and the formidable suggestion in the pose of their sworded figures affects us like the silence of murder crouching for his leap.

The Psychic Suggestion of the ‘Terrible’

The central figure of Nadir Shah dominates his surroundings. It is from this centre that the suggestion of something terrible coming out of the silent group has started. The strong, proud and regal figure is extraordinarily impressive, but it is the face and the arm that give the individuality.

That bare arm and hand grasping the rigid upright scimitar are inhuman in their savage force and brutality; it is the hand, the fingers, one might almost say the talons of the human wild beast. This arm and hand have action, murder, empire in them: the whole history of Nadir is there expressed. The grip and gesture have already commenced the coming massacre and the whole body behind consents.

Depiction of the ‘Terrible’ Soul

The face corresponds in the hard firmness and strength of the nose, the brute cruelty of the mouth almost lost in the moustache and beard. But the eyes are the master-touch in this figure. They overcome us with surprise when we look at them, for these are not the eyes of the assassin, even the assassin upon the throne.

The soul that looks out of these eyes is calm, aloof and thoughtful, yet terrible. Whatever order of massacre has issued from these lips, did not go forth from an ordinary energetic man of action moved by self-interest, rage or blood-thirst. The eyes are the eyes of a Yogin but a terrible Yogin; such might be the look of some adept of the left-hand ways, some mighty Kapalik lifted above pity and shrinking as above violence and wrath.

Those eyes in that face, over that body, arm, hand seem to be those of one whose spirit is not affected by the actions of the body, whose natural part and organs are full of the destroying energy of Kali while the soul, the witness within, looks on at the sanguinary drama tranquil, darkly approving but hardly interested.

The Deeper Intention of the Artist

And then it dawns on one that this is not so much the Nadir of history; unconsciously perhaps the artist has given a quiet but effective delineation of the Scourge of God, the man who is rather a force than a human being, the Asura with a mission who has come to do God’s work of destruction and help on the evolution by carnage and ruin.

The soul within is not that of a human being. Some powerful Yogin of a Lemurian race has incarnated in this body, one born when the simian might and strength of the vānara had evolved into the perfection of the human form and brain with the animal still uneliminated, who having by tapasya and knowledge separated his soul from his nature has elected this reward that after long beatitude, prāpya puṇyakṛtāṁ lokān uṣitvā śāśvatīḥ samāḥ, he should reincarnate as a force of nature informed by a human soul and work out in a single life the savage strength of the outward self, taking upon himself the foreordained burden of empire and massacre.

Building Upon the ‘Terrible’ Suggestion

From Nadir the coming carnage has passed into the seated warrior and looks out from his eyes at the receiver of the order. The gaze is contemplative but not inward like Nadir’s, and it is human and indifferent envisaging massacre as part of the activities of the soldier with a matter-of-fact approval. The figure is almost a piece of sculpture, so perfect is the rigidity of arrested and expectant action. The straight strong sword over the shoulder has the same rigid preparedness.

There is a certain defect in the unnatural pose and obese curve of the hand which is not justified by any similar detail or motive in the rest of the figure. We notice a similar motiveless strain in the position of Nadir’s left arm, though here something is perhaps added to the force of the attitude.

A standing figure receives the sanguinary command. The folded hands and the scimitar suspended in front are full of the spirit of ready obedience and there is an expression of pleasure, almost amusement which makes even this commonplace face terrible, for the decree dooming thousands is taken as lightly as if it were order for nautch or banquet.

The three mighty swords, by a masterly effect of balanced design, fill with death and menace the terrace on which the men are seated. Behind these formidable figures is a part of the palace gracious with the simple and magical lines of Indo-Saracenic architecture and in the distance on the right from behind a mass of heavy impenetrable green a slender tapering tower rises into the peaceful quiet of Delhi.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 1, pp. 455-458

~ Research and Design: Beloo Mehra