Editor’s note: Oeendrila Guha joins the Renaissance group of authors. In her maiden piece, she emphasises that most of Sri Aurobindo’s dramatic works address love, but it is the kind of love that aids the giver and the recipient to prepare for a divine love. She then zooms in on Sri Aurobindo’s play Eric about which Nolini Kanta Gupta had once written:

The marriage of love and heroism is the story of Eric, how heroism adds force and strength and nobility to love and how love lends grace and beauty and an other-worldly charm to force and strength.

~ Nolini Kanta Gupta, Collected Works, Vol. 4, p. 384

A slightly different version of this article was earlier published in New Race: A Journal of Integral Studies (August 2022, Vol. 8 (2). We thank the publishers of New Race for their permission to republish it in Renaissance.

The sheer volume and dimension of Sri Aurobindo’s literary output is breathtaking, to say the least, and he inspired many to take to writing. His source of inspiration is the very fountain of the “Illimitable, beyond form or name” (CWSA, Vol. 34, p. 657). To make use of John Donne’s famous conceit of “the fixed foot” and “th’ other foot, obliquely run” of a compass from the poem “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning”, “the fixed foot” represents Sri Aurobindo’s fountain of spiritual inspiration: “A living centre of the Illimitable” (Savitri, CWSA, Vol. 33, p. 79). “Th’ other foot, obliquely run signifies his genius to express “the Illimitable” in all aspects of life: yoga, scriptural texts and studies, politics, literature, sociology, philosophy, to name some.

“The fixed foot” implies his “inner centre” that “oceans out” as “tones of the Infinite” (ibid, p. 323), which can be interpreted as his polymathic nature. And as a literary wizard, the other foot “obliquely” ran a lap of literature, thereby manifesting one of the “tones of the Infinite”. Such a complete personality inspires not only an age but the aeonic game of existence.

He experimented with every category of literature other than the novel.

He was not “a creator” of the novel. (CWSA, Vol. 27, p. 547) A simple explanation to this voluntary omission is that novels “deal with the vital life of men, so necessarily they bring that atmosphere.” (ibid, p. 549) He elaborates,

The difficulty is that the subject matter of a novel belongs mostly to the outer consciousness so that a lowering or externalising can easily come.

~ CWSA, Vol. 27, p. 725

It can be presumed that the genre of the novel is neither philosophically nor psychologically deep even though it does treat a relevant theme that deals with life and human experience. If “novels deal with the vital life of men” or “the outer consciousness”, then it is not necessarily “done from the psychic of the spiritual consciousness”, hence bearing the stamp of its heightening or internalising source. The end result is “going out of the inner state of experience and stimulating the rest of the nature.” (ibid, p. 725) This is an elucidation as to why he mentioned:

If novels touch the lower vital or raise it, they ought not to be read by the sadhak. One can read them only if one can look at them from the literary point of view as a picture of human life and nature which one can observe, as the Yogi looks at life itself, without being involved in it or having any reaction.

~ CWSA, Vol. 27, p. 730

But since Sri Aurobindo attempted his hand at very specific genres, it can be assumed that was because he found these genres appropriate to do justice to his elevated and internalised inspiration and realisation. The fact that he wrote plays says that he found the dramatic genre a suitable medium to give voice to his spiritual inflatus.

Most of his dramatic pieces address love.

But it is not a vital love but a love that aids the giver and the recipient to prepare for a divine love. It is of absolute importance to love a human being before loving the Divine. This means that human love has to be experienced, furthered and purified to love the Divine. In this sense, human love must progressively manifest as divine love. As M. P. Pandit observes in ‘How Do I Begin: A Primer of Affirmative Spirituality‘:

Do not look down upon human love. Use human love to arrive at the divine Love. deepen your love by more and more self-giving. You will land in the lap of the divine Love.

~ 2005, p. 48

Sri Aurobindo’s plays address such a prospect of pristine love. They are cathartic as they absolve the reader of the age-old concepts of negation and cessation of Life as the vortex of endless desires. Hence, the very structure of his plays promises a unity of action: human love progressively becoming divine love.

Love in Sri Aurobindo’s Eric

His play Eric delves into the rubrics of love, hatred and revenge to show us that there is a fine line between them. And this fine line can be erased if one recognises and responds to a higher call or duty or if one opens oneself to a greater power that can transcend the binary. The answer of the greater power takes the form of “song.”

The employment of ‘song,’ which Aristotle considered as one of the six tenets to mastering the art of writing a perfect tragedy, is common to the classical Greek tragedies and Eric. The ‘song’ creates a certain mood, comments on a specific human and moral issue and narrates events of the past, present and future.

For example, in Antigone, the chorus or Coryphaeus creates a happy mood as the sun rises on Thebes. It mentions mythical characters, who have suffered wrongful imprisonment like Antigone, thus elevating her to the status of some of the legendary figures of heroism. It also advises against excess and evil. Moral lessons are imparted:

“Happy are they who know not the taste of evil”

~ Sophocles, The Theban Plays. Trans. E. F. Watling. Middlesex: Penguin, 1955, p. 142

or

“For mortals greatly to live is greatly to suffer.

Eric is not a tragedy, imparting moral lessons.

Nevertheless, Sri Aurobindo applied ‘song’ to tackle questions far beyond the grasp of the human intellect, and its sense of right and wrong in this play. Tragedy, as a dramatic genre, is the brainchild of the Greeks. But in the Indian context, it was not a genre per se. Rather, it was a mode of analysing issues pertaining to theology and philosophy. Such a mode was explored in Sanskrit literature by Kalidasa.

Sri Aurobindo elevated the ‘song’ by contending with issues that had no moral angle.

For instance, scene 1 of Act 1 of Eric opens with a monologue delivered by King Eric, who seeks enlightenment from Thor and Odin on how to gather strength to unite Norway. He says:

. . . O Thor

~ CWSA, Vol. 4, p. 533

And Odin, masters of the northern world,

Wisdom and force I have; some strength is hidden

I have not; I would find it out. Help me,

Whatever power thou art who mov’st the world,

To Eric unrevealed. Some sign I ask.

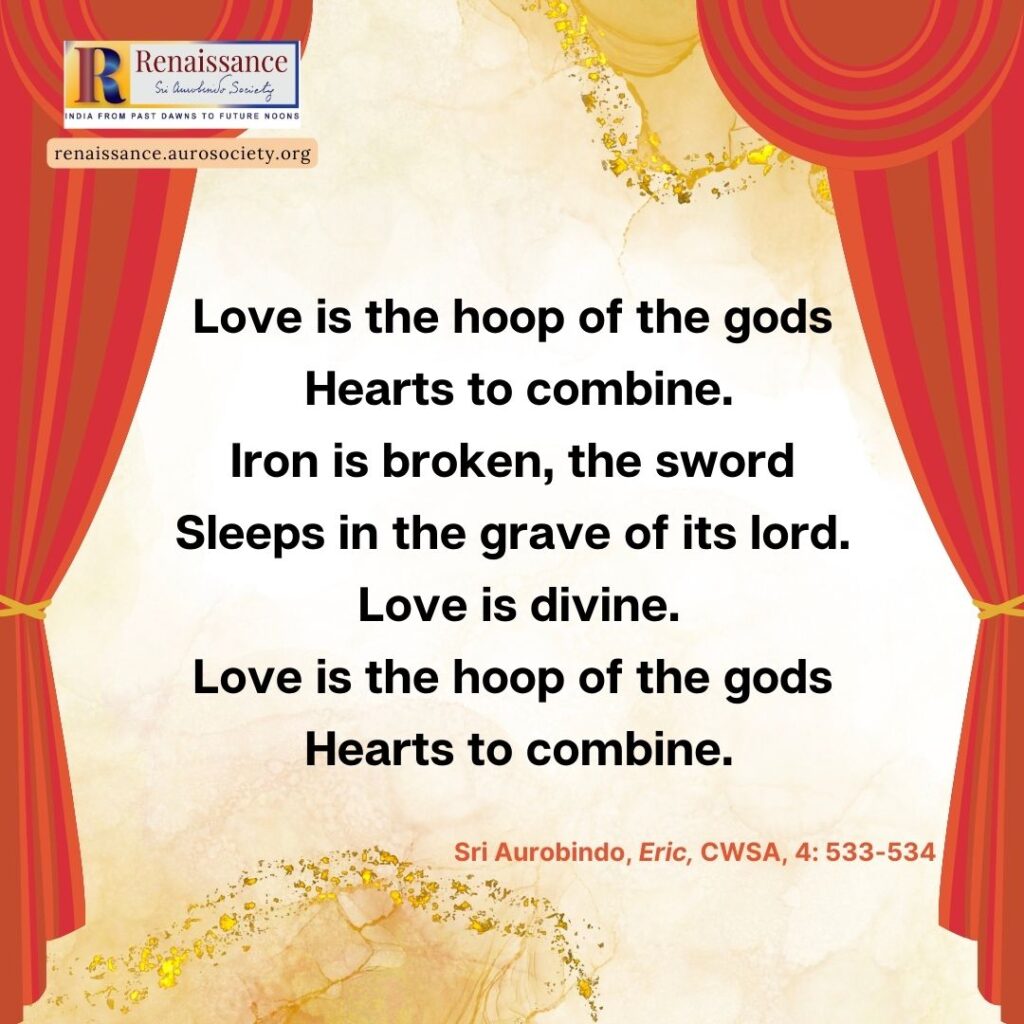

The king is a mere mortal, and he prays to Odin and Freya for a hidden strength to contain rebel forces and bring peace and unity to Norway. He aspires to be a unifying force rather than a destructive one. He aspires to be a nation builder. And Aslaug’s song is that worded reply or “sign” for Eric:

Love is the hoop of the gods

~ CWSA, Vol. 4, pp. 533-34

Hearts to combine.

Iron is broken, the sword

Sleeps in the grave of its lord.

Love is divine.

Love is the hoop of the gods

Hearts to combine.

Her words flow like a song, celebrating love.

In Twelfth Night, Orsino, Duke of Illyria, contends, “If music be the food of love, play on.” (Shakespeare, 349) Similarly, Aslaug’s song acts as “the food of love” because it fills Eric with hope and energy. It is as if the gods speak to him through her, feeding his entire being with a certitude that he will succeed in uniting Norway, but it is not by brandishing the sword but by spreading love.

Aslaug describes love as a “hoop” because a “hoop” or a circle has no beginning or end, reminding us that it connects hearts. This “hoop of the gods” unites Eric and Aslaug, in extension Norway and the rebel dynasty of Sigualdson, headed by the crown prince Swegn. Aslaug is that righteous strength that Eric prays for to unify Norway and the rebel dynasty. She embodies love even though she is Eric’s nemesis as she is sent to kill him; instead, she falls in love with him.

The strength that Eric seeks from Thor and Odin to unite Norway is not born of tyranny but love, kindness and compassion:

For unity is sweet substance of the heart

~ CWSA, Vol. 4, p. 534

And not a chain that binds, not iron, gold,

Nor any helpless thought the reason knows.

He is aware that coveting kingdoms at the point of the sword serves no purpose. He looks to snare his enemy like a lover wooing the one he loves. Eric’s love for Aslaug compels her to concede vengeance. Ergo, he does not vanquish her by wielding his sword but captivates her with his love:

. . . From thy bosom my strength

~ CWSA, Vol. 4, p. 616

Comes out to me. Mighty indeed is love,

Thou sangst of, Aslaug, once, the golden hoop

Mightier, swifter than the warrior’s sword.

In this manner, Sri Aurobindo made perfect use of ‘song’ to predict the union of two individuals and their people.

He also divulged a maxim, that of love as a divine and transformative Force. Eric’s love for Aslaug enriches him: he understands Swegn’s anger, wisely pardons him, shares with him his bounty and makes him the head of the Norwegian army. Eric’s love for Aslaug gives life to Swegn, whose love for his wife and sister trumps his hatred of Eric. Eric imparts the message of love, that love forgives, embraces and includes. After all, Juliet famously says:

My bounty is as boundless as the sea,

~ The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Oxford & IBH, 2007, p. 913

My love as deep; the more I give to thee,

The more I have, for both are infinite

Thus, Sri Aurobindo elevated the ‘song’ by superseding moral issues that were of the greatest importance to the Greek dramatists, who invariably used chorus to comment on the moral nature of the hero’s thoughts, actions and feelings.

The Greek dramatists advocated a fall from moral grace to be delivered by deus ex machina. Sri Aurobindo suggested opening oneself to a higher Force, becoming and remaining a medium of Its expression. The Divine is no avenging entity that comes to humanity’s succour only when it falls from moral grace. Manifestation is not a contrived plot, to be rescued by a miraculous entity that waits till the very last moment to save a life that has failed morally!

It is on record that during the last three years at St. Paul’s School, London, Sri Aurobindo “simply went through his school course and spent most of his spare time in general reading, especially English poetry, literature and fiction, French literature and the history of ancient, mediaeval and modern Europe.” (Autobiographical Notes: 28)

His prolific reading of “the history of ancient, mediaeval and modern Europe” is displayed in his penmanship of Eric.

. . . No specific source of the plot of Eric is known. Sri Aurobindo seems to have made free use of names and events from the history of Norway in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries, a period that was the subject of much mediaeval Scandinavian literature.

~ CWSA, Vol. 4, p. 1003

The ‘Dramatic Arc’ in Eric

His prolific reading of “the history of ancient, mediaeval and modern Europe” not only shaped content but also style. Eric brings to light Sri Aurobindo’s scholastic perusal of Greek and Latin literature characterised by the five-act structure or five essential sections to build “one developing action”. The play observes the traditional five-act structure, which was introduced by the ancient Greeks and proficiently applied by William Shakespeare.

The five-act framework was in prevalence till the eighteenth century after which the three-act structure of beginning, middle and end gained currency, as demonstrated in the works of Henrik Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw. But Sri Aurobindo, going against the tide, chose to continue with the five-act structure in all his plays.

According to Gustav Freytag, the five-act play guarantees an analytically-framed plot with equidistant developments from one act to another. Act 1 exposes, hence called exposition or introduction, Act II offers rising action, Act III waxes into a climax, Act IV wanes into falling action, and Act V concludes with a dénouement. This precise and equidistant development is called by Freytag the “dramatic arc”.

This “dramatic arc” is clearly visible in Eric.

Act I serves as an exposition to Eric because it introduces Eric and Aslaug, the latter’s murderous plot to dispose of Eric to seek revenge on the unwarranted exile of her brother, Swegn, who was banished to Trondhjem.

Act II offers rising action.

In the course of this Act, Aslaug falls in love with Eric, but she knows where her duty lies. So, she sets out to carry the brilliant plan woven by Hertha, wife of Swegn, to kill Eric. Hertha, who accompanies Aslaug to Norway and gained entrance to Eric’s court as a dancing girl, divulges to Eric her relation to Swegn and Aslaug.

Eric learns from Hertha Aslaug’s plan to avenge her brother by neutralising Swegn is the rightful ruler of Norway for he is the son of Olaf, who was once “Norway’s head”. But even as she meets with Eric on that fatal night, her resolve sways: “She lifts the dagger twice, lowers it twice, then flings it on the ground.” (CWSA, Vol. 4, p. 587) She submits to her heart and professes her love for Eric, who then prepares for a war against Swegn.

From our archives:

Studies in Sri Aurobindo’s Dramatic Poems

Act III delivers climax. Aslaug is determined to take Eric’s life, but she is in a quandary. Between her duty to her brother and her love for Eric, she chooses the latter as she lifts her dagger twice but lowers it twice, finally laying it down on the ground.

Act IV narrates falling action because Eric does not wage a war against Swegn.

He sends his trusted Gunthar to Swegn with an offer. We learn that Eric did not usurp the throne, as earlier suspected. Rather, he was elected by his peers to rule Norway. Obviously, Swegn, feeling cheated of his birthright, played an underhanded part to undermine the newly enthroned Eric, who is fully aware of the former’s root of affliction:

The causes and the griefs that raise thee still

~ CWSA, Vol. 4, p. 597

Against my monarchy. . .

But thou, against thy country’s ancient laws

Rebelling, hast preferred for judge the sword.

In the missive, the king of Norway promises to revoke Swegn’s banishment and grant him Trondhjem’s earldom, honours and wealth if he were to accept Eric as Norway’s rightful monarch. Swegn considers Eric’s ultimatum with his earls and decides to visit Eric.

Act V sees the dénouement, that of Swegn accepting Eric’s offer: on finding both Hertha and Aslaug captives of Eric, Swegn yields. And Eric, on realising how demeaning it must be for Swegn to admit defeat, surprises him with an equally exalting offer of

Four prisons I assign to Olaf’s son.

~ CWSA, Vol. 4, p. 613

Thy palace first in Trondhjem, Olaf’s roof —

This house in Yara, Eric’s court — thy country

To whom thou yieldest, Norway — and at last

My army’s head when I invade the world.

The unity of action in this play confines action to a set of events that are correlated as cause and effect.

As one of the causes is the wrongful banishment of Swegn, its effect is Aslaug’s murderous plot to dispose of Eric. As one of the causes is Aslaugh’s love for Eric, its effect is Eric’s gift of Trondhjem’s earldom, honours and wealth to Swegn.

One can clearly distinguish the “dramatic arc” in Eric because Sri Aurobindo, the dramatist, accommodated the plot by progressing from one act to another while maintaining “one developing action” that is limited to a set of events that are related as cause and effect.

It is small wonder that Sri Aurobindo, the peerless dramatist, was well-versed in mediaeval Scandinavian literature and Greek literature and could compose a five-act play by stringing together Norse deities and human beings in the like of the classical Greek plays but with the soulful deliberation on issues pertaining to theology and philosophy that supersede right and wrong.

About the author:

Oeendrila Guha is an alumnus of Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education, Pondicherry, and Pondicherry University. Currently, she is working at a content technology enterprise. She regularly contributes articles and papers to journals related to Sri Aurobindo’s thought and vision.

~ Design: Beloo Mehra