Editor’s Note: In this brief biography of Nandalal Bose, a pioneer of what came to be known as Contextual Modernism school of Indian painting which emerged from Shantiniketan, read about the various artistic, philosophical and spiritual influences that shaped him as an artist. Nanadalal was a student of Abanindranath Tagore, the leading light of the Bengal School of Art, and later worked and taught at Shantiniketan where he found his own unique approach to integrating art and life.

Sri Aurobindo wrote:

“…the whole power of the Bengal artists springs from their deliberate choice of the spirit and hidden meaning in things rather than their form and surface meaning as the object to be expressed.”

Nandalal Bose, surely personified this, “power of the Bengal artists.” He was born on December 3, 1882, in the Munger district of Bihar. His first introduction to art was through his mother, who made mud toys for him. Nandalal keenly watched the potters and craftsmen on the way to his school. The way they they used materials and the subtle touch that gave shape to things – these observations left an impression on him.

At the age of 15, he moved to Kolkata to pursue further education, but traditional academics bored him. Interested in art, he learned sketching from one of his cousins and started copying paintings. When he saw some paintings of Abanindranath Tagore, a noted artist, and nephew of Rabindranath Tagore he found his answer to the question he wasn’t even sure he had.

Making of an Artist

The established artists of the day used Western techniques and styles. Abanindranath was one of the pioneers who had freed himself from European influence and worked along the Mughal and Rajput styles. The art education in the country at the time, managed by the British, ignored Indian artistic practices and processes. E.B. Havell was an English art historian who truly loved India. When he was appointed the principal of the Government School of Art in 1896, he, along with Abanindranath who was the vice-principal, developed an art curriculum on Indian lines. In 1905 Nandalal approached Abanindranath, intending to pursue art, and was referred to Havell for an interview. Havell liked his original works done in the Indian way and accepted him as a student.

Nandlal had found his Guru in Abanindranath Tagore. Once when Nandlal’s father-in-law expressed a concern that his son-in-law would have no career if he pursued art, Abandinranath assured him, “I have taken all responsibility of Nandalal”.

Several other important things going on at the time also deeply influenced Nandalal’s art. He keenly observed the unfair and oppressive practices of the British empire. His friend, Debabrata Bose, who was also an associate of Sri Aurobindo, narrated to him accounts of the country’s plight. Nandalal’s heart pained for the motherland; the daily insults faced by an average Indian infuriated him. All these experiences shaped him to be a nationalist.

Spiritual Guidance

Sister Nivedita, the disciple of Swami Vivekananda, was also working for the revitalization of Indian Art. She collaborated closely with Havell and Abanindranath and saw Nandalal’s works during one of her visits to the Art college. This was a deeply influential meeting for Nandalal. She introduced Nandalal to the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna. He had several darshan-s of Sarada Devi, the Holy Mother, and got acquainted with some of the direct disciples of Sri Ramakrishna.

Throughout his life, he maintained a deep, respectful relationship with the Sri Ramakrishna Mission. Later he designed the temple built at Sri Ramakrishna’s birthplace and offered his designs for some of the panels in Belur Math. He looked for spiritual guidance and inspiration in Sri Ramakrishna. He once mentioned how Sri Ramakrishna was a keen observer and preserver of art; while outwardly simple, he was always neat and organised, qualities that are important for an artist.

Mahendranath Dutta, the younger brother of Swami Vivekananda, encouraged Nandalal to paint. Girish Ghosh, another famous disciple of Sri Ramakrishna advised Nandalal to identify inwardly with the subjects of his painting. The discourses by the monks of Ramakrishna Mission on Bhagavad Gita and Ramayana nourished his soul as well as developed his imagination. But the most important help came from Sister Nivedita, who provided him with critical feedback on his work and took care to see that he was trained as a complete artist.

Experiential Learning

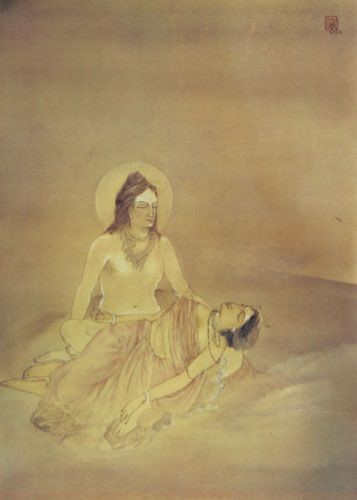

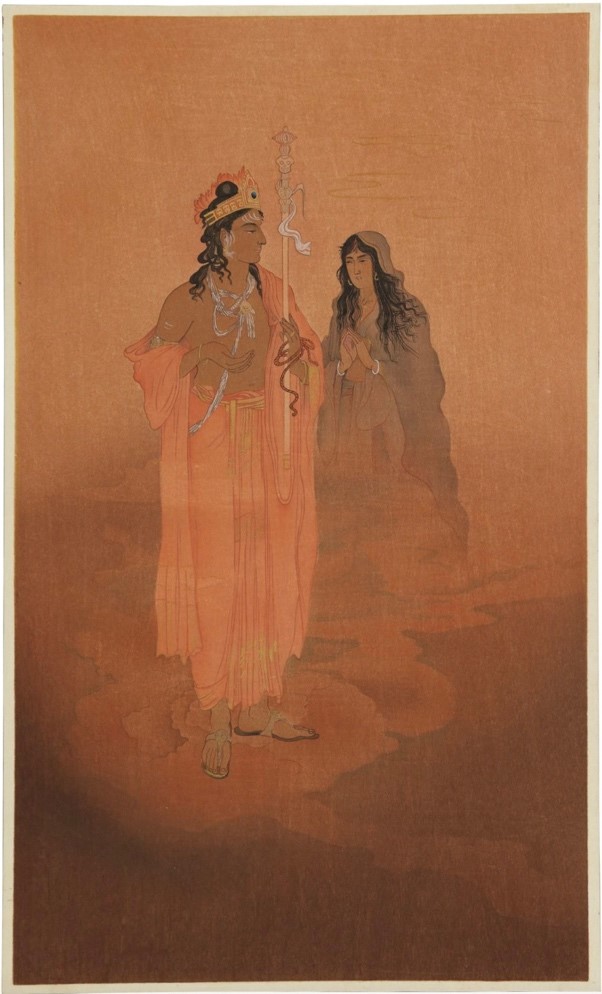

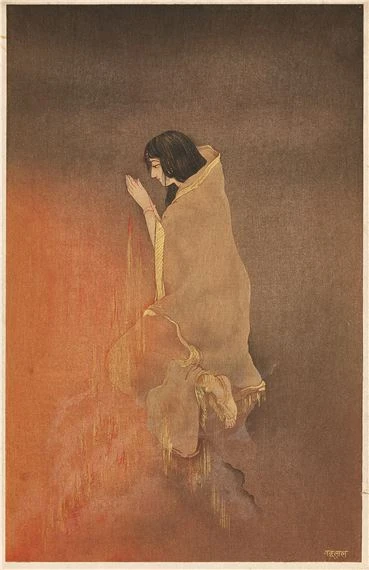

In 1907, Abanindranath Tagore co-founded the Indian Society of Oriental Art to cultivate and educate about Indian Art. At the society’s exhibition, Nandalal showcased two of his works, “Siva and Sati” and “Sati”. Impressed by his talent the Society gave him a cash prize of Rs. 500, a sizeable sum at that time. He used the money to fund his trip to have an experiential learning of Indian art. He visited some of the notable historical locations of Northern and Southern India, covering key Hindu, Buddhist, and Mughal sites.

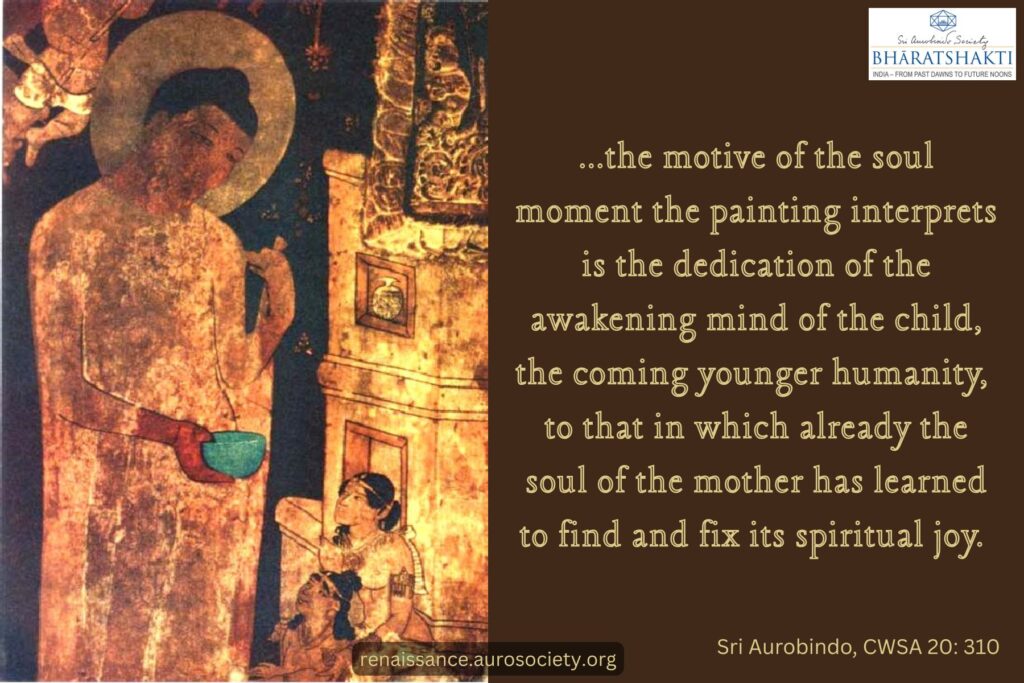

In 1909, Lady Herringham along with a team of Western artists came from England to prepare copies of Ajanta murals. Sister Nivedita with her persistent efforts arranged a sponsorship for Nandalal and pushed him to join the project. He was initially reluctant as it was a very remote site with no decent accommodation. He along with the other two pupils of Abanindranath ultimately joined the team.

Till now Nandalal had only seen examples of sculptures and miniature art. The vast murals of Ajanta, with a rich variety of themes and figures, capturing the movements, captivated the imagination of the artist. It was an unforgettable experience for him. In those days, Bengali youth were in general suspected as revolutionaries. The Indian artists traveling in the team were detained by police while returning, till Sir John Woodroffe, another India-lover British intervened!

Sati by Nandalal Bose, 1907

Gaining Recognition

Nandalal’s works were getting recognised, drawing the attention of the press. His painting “Sati” was reproduced in a reputed Japanese Magazine. He was given a position at Government Art College, but he chose to stay with his guru at the Indian Society of Oriental Art. Through Tagore household he met Okakura, a reputed Japanese art critic, and later Kampo Arai, a Japanese reproduction artist.

Nandalal learned the Japanese techniques, he appreciated the idea of capturing flow of life through brush strokes. Okakura once said that art stands balanced on three pillars — observation, tradition, and creation. These words stayed with Nandalal forever. An idea of Pan-Asian Art also began to take shape. He got more deeply acquainted with Rabindranath Tagore, who would ultimately invite him to take charge of Kala Bhavan (the College of Arts at Viswa Bharati).

Flourishing at Shantiniketan

This opportunity came just at the right time for Nandalal. He had been, for some time, finding the Kolkata atmosphere stifling. The Oriental Art Society which depended on the Government grants was getting too administrative. Rabindranath Tagore offered him complete artistic freedom, the free nature of Shantiniketan attracted him. The fact that Tagore himself decided on the policies of the institution, sheltering it from the English interventions, was a great attraction. Nandalal joined Kala Bhavan in 1921.

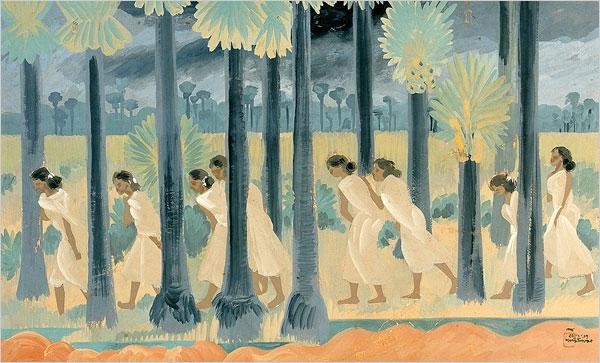

At Shantiniketan, Nandalal’s artistic talent flourished in different directions. Tagore wanted art to be an integral part of life. Nandalal gave a practical shape to this ideal. He and his students painted frescoes on different buildings, bringing art to the forefront. Indian paintings that were limited to miniature art regained their ancient bold self as in the murals of Ajanta.

***

Nandalal did illustrations for several books of Tagore, including the kindergarten book introducing children to Bengali alphabet. He designed the stage, dress, and ornaments for different dramas staged by Tagore. All these were achieved creatively using basic local materials on a very tight budget. Influenced by the free life, the themes of his paintings expanded to include landscapes and village life. He used Indian colours and materials, often sourced locally, eschewing European materials. As a teacher, he worked with each student individually, not disturbing the natural tendency of the pupil, giving each one the freedom to grow, but rooted in Indian traditions.

He visited China, Japan, Myanmar, and Java with Tagore in 1924, and later to Sri Lanka. These journeys enriched the artist in him. He brought back to Shantiniketan new art forms such as Batik and leather crafts. He continued to learn, his life reminds us of Sri Aurobindo’s quote, “To be perpetually reborn is a condition of material immortality” (CWSA, Vol. 23, p. 5).

Art for Indian Constitution

Tagore passed away in 1941. India gained political freedom in 1947, and Indian Constitution was adopted in November 1949. Nandalal Bose was assigned the task of illuminating the handwritten copy of the Constitution, to represent the journey from an ancient civilization to the present-day modern nation. Nandalal and his team, through a series of 22 paintings, depicted the historical journey of India — from the Indus Valley to the age of Ramayana, from the Buddhist and Jain periods to Gupta age, and from the Mughal period to the modern freedom movement. He also designed the emblem of the awards given by the Indian Government.

Nandalal retired from his post at Kala Bhavan in 1951 after a service of three decades. Awards started flowing from different directions — Doctor of Letters, Padma Vibhushan, and ellowships at various institutions such as Lalit Kala Academy and the Asiatic Society. But he remained unperturbed, continuing his daily life of waking up at 3:00 AM, reading Bhagavad Gita and works on Sri Ramakrishna or Sri Aurobindo, followed by a walk in the nature to collect materials for his art. He passed away on April 16, 1966, after a fruitful service to the revival of Indian Art. His approach to art is summarized in a sentence that he wrote as an advice to one of his students:

“If there is devotion to the Divine in the heart, then one can paint well.”

Bibliography

- Nandalal Bose, The Doyen of Indian Art by Dinkar Kowshik , National Book Trust

- Centenary Issue of Nandalal Bose, Bengali Magazine Desh, December 1982

- An Album of Nandalal Bose, with a Biographical Note, Shantiniketan Asramik Sangha, 1956

- Letters of Sister Nivedita, Vol. 2, 388, letter No. 728, to Mr. and Mrs. S. K. Ratcliffe, 23 February 1910, Advaita Ashrama