Volume V, Issue 10

Author: V.K. Gokak

CONTINUED FROM PART 1

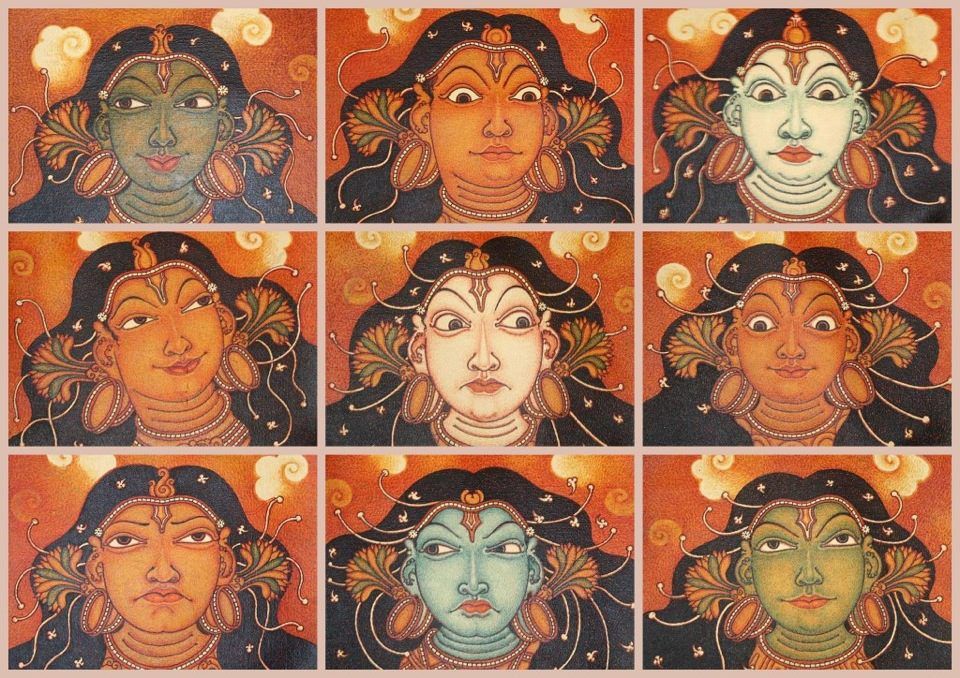

Editor’s note: Is there a primary rasa from which other rasa-s originate? In what way is rasa an attribute of the soul? Before we read the author’s insights on these questions, let us meditate on this small clip depicting the Navarasa.

Rasa: The Seership of the Artist

It has been shown that Rasa connotes the Supreme Reality. In what manner or measure does it reside in the artist, the seeing eye? There are significant statements made on this subject in Sanskrit literature which, to the casual reader, sound partial, dogmatic and contradictory. But a golden thread of meaning runs through them and it yields itself to intimate scrutiny and inquiry.

Bhavabhuti in his Uttararāmacarita, Act III. 47 speaks of karuṇa (pity or sympathy) as the only rasa:

एको रसः करुण एव निमित्तभेदाद्

भिन्नः पृथक्पृथगिवाश्रयते विवर्तान्।

आवर्तबुद्बुदतरंगमयान्विकारा-

नम्भो यथा सलिलमेव हि तत्समस्तम्॥eko rasaḥ karuṇa eva nimittabhedād

bhinnaḥ pṛthakpṛthagivāśrayate vivartān।

āvartabudbudataraṃgamayānvikārā-

nambho yathā salilameva hi tatsamastam॥There is only a single rasa — pity or sympathy, but it takes different forms since it changes in response to circumstances that are changing; just as water forms into whirlpool, bubble or wave but in the end it all remains the same: nothing but water.

What Bhavabhuti wished to indicate was that pity or sympathy is the basic rasa or sentiment. He caught a glimpse of the soul through this particular attribute or manifestation. In other words, sympathy seemed to him to be the inherent and perennial condition of the soul and other emotional states only fleeting or transitory. That the soul in its fullest blossoming manifests universal sympathy is clear. But it has other and equally glorious attributes. These Bhavabhuti did not stop to consider. Again, cittavidruti or the melting of consciousness is not the only kind of aesthetic experience possible to man.

Another poet, on the other hand, maintains that śānta is the only rasa, and the source of all other rasa-s, as quoted in A. Sankaran’s work, titled, Some Aspects of Literary Criticism in Sanskrit (1973, p. 116.)

स्वं स्वं निमित्तमासाद्य शान्ताद्भावं प्रवर्तते।

पुनर्निमित्तापाये तु शान्त एव प्रलीयते॥svaṃ svaṃ nimittamāsādya śāntādbhāvaṃ pravartate।

punarnimittāpāye tu śānta eva pralīyate॥All the emotional states obtain their respective determinants and proceed from śānta. They merge again in śānta as soon as the determinants are withdrawn.

Abhinavagupta also believes that contemplative delight, the essence of which consists in disinterested and supersensuous perception, is itself of the nature of śānti or Calm – “calm of mind, all passion spent” as Milton would have it. This view obviously starts from a glimpse of another attribute of the soul — the depth and not the tumult of the soul; or its ineffable peace. All other modes of experience are, for Abhinavagupta, relative avenues of approach. The Absolute is realised only in peace. That is why he regards śānta as the basic rasa or the primary attitude of the soul.

Bhoja, on the other hand, remarks that śṛṅgāra is the only rasa: एते रत्यादयो भावाः शृंगारव्यक्तिहेतवः ete ratyādayo bhāvāḥ śṛṅgārvyaktihetavaḥ (Sringara Prakasha, Chapter XIV). This śṛṅgāra is not to be confused with erotic sentiment. It is, as Dr. Raghavan explains, the inner tattva of ego or man’s love for his own Self. Ahaṅkāra is Ego or awareness. This awareness is called abhimāna when it is projected on an object and gets attached to it, deriving pleasure even out of a painful spectacle. These various projections culminate again, each in its own right, in prema or love. This exalted awareness — consciousness projecting itself into an object and then transforming itself into love — is śṛṅgāra.

All bhāva-s or moods are, according to Bhoja, of the form of love. The valiant man fights because he loves to fight; the clown jokes because he loves to laugh. It is this universality of love that, according to Bhoja, is the distinctive attribute through which the soul manifests itself. All other emotional states are derivatives. Aesthetic experience, after passing through manifold forms, attains again the status of prema, of love or delight.

Dharmadatta throws open another casement of the soul.

रसे सारश्चमत्कारः सर्वत्राप्यनुभूयते।

तच्चमत्कारसारत्वे सर्वत्राप्यद्भुतो रसः॥

तस्मादद्भुतमेवाह कृती नारायणी रसम्।rase sāraścamatkāraḥ sarvatrāpyanubhūyate।

(Sahitya Darpana, Parichheda III)

taccamatkārasāratve sarvatrāpyadbhuto rasaḥ॥

tasmādadbhutamevāha kṛtī nārāyaṇī rasam।

All other rasas are said to be but varying manifestations of the one adbhuta (the marvellous). Viswanatha, who presents this view, prizes chittavistāra or the heightening of consciousness, not vidruti, the melting of consciousness. An object which is a guest of the marvellous hour of inspiration reveals its innermost reality to the seeing eye and this reality dazzles the eye with its marvellous effulgence.

Aesthetic experience culminates in chamatkāra, in the light that never was on sea or land. The soul makes the natural supernatural by flooding the natural with its own light. This is done through āvaraṇabhanga or the dis-environing of the Inner Effulgence. This effulgence or prakāsha is one of the attributes of the soul. But Viswanatha claims that it is the distinctive attribute and that all the others derive from it.

Universal sympathy, ineffable peace, universal love, marvellous effulgence, — these, then, are the attributes of the soul, each one of which has been claimed as its primary manifestation. But the soul (psyche) itself is a complex or many-faceted manifestation of the Jivatman, – the Individual Divine. It has many names and aspects and each seer prizes the name and aspect through which the soul has manifested itself to him.

When the evolving psychic entity in the individual reaches its full flowering, the name and aspect which were primary to him are but part of a shining multitude, — an effulgent host of names and aspects; or, rather, that other primaries lurk behind the one primary that the individual has experienced. What is primary is the soul, not its attribute or attributes.

It is clear that in the foregoing discussion, the adbhuta and other rasa-s are interpreted as manifestations of the soul, not traditionally as delineations of wonder, pity, etc., with their sensuous and mundane associations. It is obvious that this is the only tenable sense if they are to be spoken of as ‘primaries’.

CONTINUED IN PART 3

~ Design: Beloo Mehra