Volume III, Issue 2

Author: Renaissance Editor

Editorial note: As an offering for the Mother’s birthday, we highlight a beautiful facet of her Divine personality – the Mother as an artist. This may also be seen as an expression of one facet of her Mahalakshmi aspect, an embodiment of Divine Beauty and Harmony.

The selections about the Mother as an artist are excerpted from the book ‘Paintings and Drawings by the Mother’ (e-version available HERE). A few relevant passages from the Mother’s Works are included for some more light on the Mother’s futuristic vision of art and beauty. Only a few formatting revisions have been done for ease of online readability.

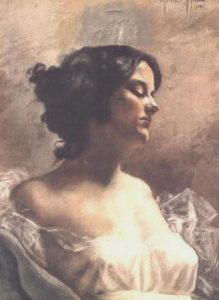

The Mother did not give her personal career as an artist a primary importance. Hence it is not commonly known that she was an accomplished artist. . . . in spite of her limited artistic activity in later years, she never lost the power of her observing eye nor the sureness of her hand, nor did she allow her consciousness of beauty and her aesthetic vision to become diminished in the midst of her intensive spiritual endeavours and manifold responsibilities as the head of Sri Aurobindo Ashram.

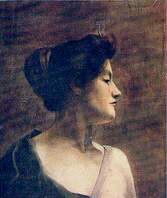

The Mother loved to draw and paint from her childhood. Though art was only one of her many interests, it occupied a prominent place in her early life. She began to take drawing lessons at the age of eight. Two years later she started to learn oil painting and other painting techniques. By the time she was twelve she was doing portraits. In 1892, when she was fourteen, one of her charcoal drawings was exhibited at the International “Blanc et Noir” Exhibition in Paris.

Having completed her regular schooling at the age of fifteen, she joined an art studio in Paris to study painting. In all likelihood it belonged to the Academic Julian, an organisation with several studios founded by Rodolphe Julian in the latter part of the nineteenth century. In those days women were not admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. . . .

The Mother continued to work in this studio until 1897, when she married the artist Henri Morisset. During the next few years, she participated in the stimulating artistic life of turn-of-the-century Paris and associated with some of the leading artists of the period.

Her Paintings in Paris and Japan

She did a fair amount of painting, both in Paris, where she and Morisset had their flat with a studio in the garden, and on trips to the countryside. Six of her works were exhibited in the prestigious Salon de la Societe Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1903, 1904 and 1905. These works are listed by name in the catalogues of the Salon; one of them was reproduced in the illustrated catalogue of the 1905 exhibition.

Only about forty of the Mother’s paintings are available to us today. More than half of these belong to her early years in France (before 1914, when she made her first trip to India), including her visits to Algeria (1906 and 1907). Other early works, which she considered to be among her best, were either sold or presented to friends and are now lost to us.

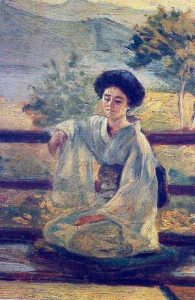

The Mother also did a number of paintings and drawings while she was in Japan, between 1916 and 1920. There she acquired the Japanese technique of water-colour painting, working directly with brush and black India ink. When she returned to India in 1920, she brought with her seven paintings and some drawings which she had done in Japan.

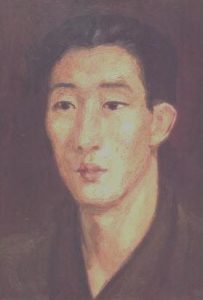

Portraits in Pondicherry

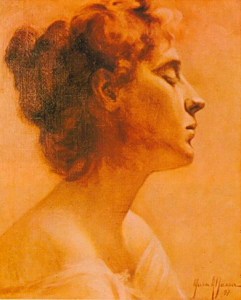

In Pondicherry, the Mother rarely had time to undertake oil paintings. Her spiritual work and practical responsibilities became all absorbing and she preferred to bring out latent artistic faculties in others rather than display her own abilities.

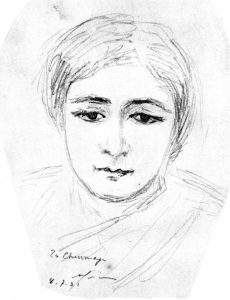

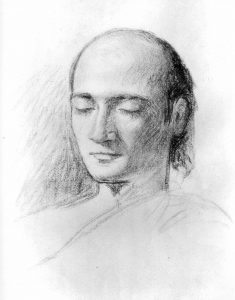

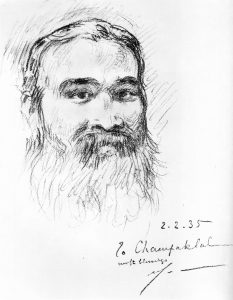

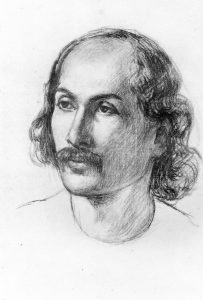

But she did quite a few drawings of the highest quality and artistic value. These are mainly portraits. Those who saw her doing these portraits describe how within minutes, with a few rapid strokes, a living face would be completed.

The Mother herself did not attach much importance to what she had produced as an artist. No doubt, she could have done much more if she had chosen to apply her talent, training and spiritual vision to serious painting in her mature years. Her early works, for all the skill and beauty we may admire in them, are in a style which may be said to belong to the past. The Mother was well aware of this.

She spoke of the future of art in her talks, yet she did not herself attempt to realise its highest possibilities as she saw them. She left this for others to attempt. When she was urged to take up painting again, she replied that she had no time for it. Her later drawings were generally a spontaneous expression on the spur of the moment, not a premeditated artistic creation.

The Mother on Future of Art

Also Read:

Free Progress: The Mother, an Educationist of the Future

Art as a Discipline for Developing the Consciousness

It must be remembered that even from childhood the Mother was conscious of a larger mission to which art and all other interests were subordinate. Art was for her a valuable part of life, but not the most important thing. It was a language which came naturally to her, and she used it as a means of expression and communication in the course of her work with people. For her, images could often reveal more than words.

She regarded her art study in her early years as a discipline for developing the consciousness, not as a preparation for a brilliant career or a life dedicated to art for art’s sake. Once she had mastered painting to a sufficient degree for her purposes, she moved on to other things.

Some remarks on specialisation the Mother made to a group of students are typical of her attitude:

“This is something I have heard from my very childhood, and I believe our great grandparents heard the same thing, and from all time it has been preached that if you want to succeed in something you must do only that. And as for me, I was scolded all the time because I did many different things! And I was always told I would never be good at anything. I studied, I did painting, I did music, and besides was busy with other things still.

~ CWM, Vol. 6, p. 19

And I was told my music wouldn’t be up to much, my painting wouldn’t be worthwhile, and my studies would be quite incomplete. Probably it is quite true, but still I have found that this had its advantages—those very advantages I am speaking about, of widening, making supple one’s mind and understanding. It is true that if I had wanted to be a first-class player and to play in concerts, it would have been necessary to do what they said.

And as for painting, if I had wanted to be among the great artists of the period, it would have been necessary to do that. That’s quite understandable. But still, that is just one point of view. I don’t see any necessity of being the greatest artist, the greatest musician. That has always seemed to me a vanity.”

Drawing with Closed Eyes

The story behind one of the portrait-sketches is of interest for the light it sheds on the Mother’s method of drawing. The portrait of Champaklal done on 2nd February 1935 is unique in that it was done with closed eyes. When the Mother took the picture to Sri Aurobindo she said, “The pencil just went on moving.”

Though this kind of feat was not the Mother’s normal practice, it is a striking illustration of a principle on which she more than once insisted, namely, that the hand must acquire its own consciousness:

“I have told you that no matter what you want to do, the first thing is to put consciousness in the cells of your hand. If you want to play, if you want to work, if you want to do anything at all with your hand, unless you push consciousness into the cells of your hand you will never do anything good—how many times have I told you that? And this is felt. You feel it. You can acquire it.

~ CWM, Vol. 4, p. 403

All sorts of exercises may be done to make the hand conscious and there comes a moment when it becomes so conscious that you can leave it to do things; it does them by itself without your little mind having to intervene.”

Guiding the Ashram Artists

The Mother gave her help and encouragement to a number of people in the Ashram who wished to draw and paint, both beginners and trained artists.

The results were varied, often original and sometimes remarkable. For two or three aspiring artists she herself made sketches and suggested compositions. The paintings of Chinmayi (Mehdi Begum) display an impressionistic style and carry a great deal of the Mother’s training and influence. The Mother demonstrated the technique of oil painting to Barin, Sri Aurobindo’s brother, in the 1920s, to Sanjiban in the 1930s and to Huta in the 1950s.

Sanjiban has recounted how the Mother introduced him to oil painting after he had made sufficient progress in painting with pastel colours:

“I wanted to do oil painting. The colours and brushes were ordered from Calcutta and paid for by Mother. She asked me to meet her at 10.30 in the morning on Pavitra’s verandah. She had an old piece of canvas ready and called Chinmayi to pose for her. Then she showed me how to take out the colours and arrange them on the palette. She gave me a palette knife which she had used and asked me to keep it with me.

“Then she painted Chinmayi—only her face, forehead, hair and the background. While she painted she talked. “Do not put direct dark colours on the head,” she said, “first put the facial colours and then the dark colours—this will give a better impression. If you put black directly, it will give the impression of a hole.”

“Then she asked, “Do you know how to do the background?” She took another brush and did the background. “See, the head is not touching the background. There is space in between.” Then she blended the edges of the hair with the background.”

This portrait of Chinmayi has not been found.

Savitri Paintings by Huta

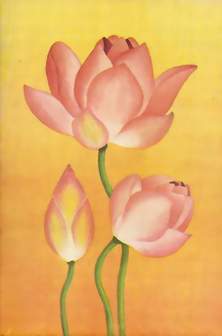

The Mother encouraged Huta to illustrate Sri Aurobindo’s epic poem, Savitri, and herself made sketches for the paintings. . .

Naturally, the actual execution of the paintings represents Huta’s style and ability and cannot be considered identical to what the Mother would have done with her own hand. Yet these “meditations on Savitri” give a hint of the kind of mystical imagery and symbolic expression she might have employed if she had taken up painting again in her later years.

Their purpose is, in the Mother’s own words, to make us “see some of the realities which are still invisible for the physical eyes.” The work with Huta in the 1960s on the illustration of Savitri was the Mother’s last substantial involvement with art.

***

To learn more about the Mother as an artist and her work with several artists at the Ashram, we recommend watching this documentary made for Acres for Auroville.

You may also enjoy:

Antaryatra — An Artist’s Journey Within (Video)

~ Design: Raamkumar