Volume V, Issue 11-12

Author: Sri Aurobindo and the Mother

Editor’s Note: What is the characteristic method of the Indian artist? Sri Aurobindo explains in the featured passage that an artist must see first in his spiritual being the truth of the thing he must express. He then creates its form in his intuitive mind. In this way, his art-creation process is akin to a yogic process. And here he is essentially different from his Western counterpart who generally looks out first on outward life and Nature for his model, or looks up to an authority, a style rule-book, or mental suggestions.

We follow this with a relevant conversation of the Mother in which she explains how an artist must make a personal contact with the Divinity hidden in the thing he wishes to express through his art.

The Origin of All Great Artistic Work

All great artistic work proceeds from an act of intuition, not really an intellectual idea or a splendid imagination,—these are only mental translations,—but a direct intuition of some truth of life or being, some significant form of that truth, some development of it in the mind of man. And so far there is no difference between great European and great Indian work.

Where then begins the immense divergence?

It is there in everything else, in the object and field of the intuitive vision, in the method of working out the sight or suggestion, in the part taken in the rendering by the external form and technique, in the whole way of the rendering to the human mind, even in the centre of our being to which the work appeals.

The European artist gets his intuition by a suggestion from an appearance in life and Nature or, if it starts from something in his own soul, relates it at once to an external support. He brings down that intuition into his normal mind and sets the intellectual idea and the imagination in the intelligence to clothe it with a mental stuff which will render its form to the moved reason, emotion, aesthesis.

Then he missions his eye and hand to execute it in terms which start from a colourable “imitation” of life and Nature—and in ordinary hands too often end there—to get at an interpretation that really changes it into the image of something not outward in our own being or in universal being which was the real thing seen. And to that in looking at the work we have to get back through colour and line and disposition or whatever else may be part of the external means, to their mental suggestions and through them to the soul of the whole matter.

More by Sri Aurobindo in this issue:

The Great Impersonal Creators and Their Living Creations

The appeal is not direct to the eye of the deepest self and spirit within, but to the outward soul by a strong awakening of the sensuous, the vital, the emotional, the intellectual and imaginative being, and of the spiritual we get as much or as little as can suit itself to and express itself through the outward man. Life, action, passion, emotion, idea, Nature seen for their own sake and for an aesthetic delight in them, these are the object and field of this creative intuition.

The something more which the Indian mind knows to be behind these things looks out, if at all, from behind many veils. The direct and unveiled presence of the Infinite and its godheads is not evoked or thought necessary to the greater greatness and the highest perfection.

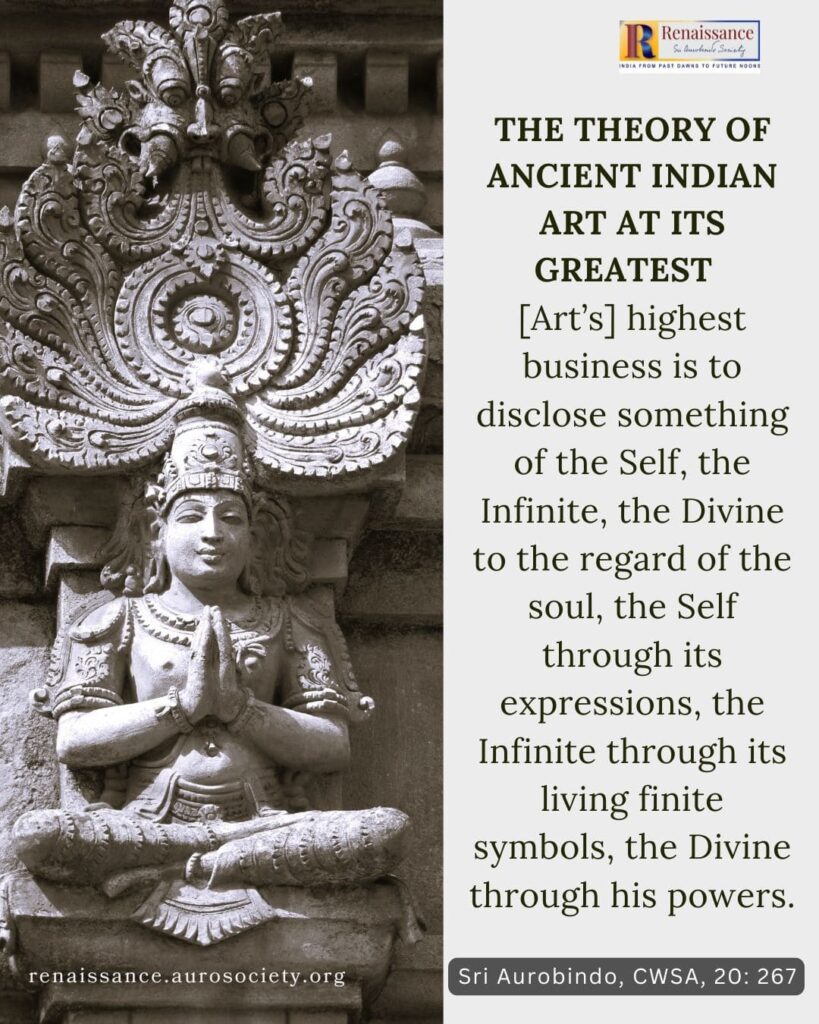

Ancient Indian Art at its Greatest

The theory of ancient Indian art at its greatest—and the greatest gives its character to the rest and throws on it something of its stamp and influence—is of another kind. Its highest business is to disclose something of the Self, the Infinite, the Divine to the regard of the soul, the Self through its expressions, the Infinite through its living finite symbols, the Divine through his powers. Or the Godheads are to be revealed, luminously interpreted or in some way suggested to the soul’s understanding or to its devotion or at the very least to a spiritually or religiously aesthetic emotion.

When this hieratic art comes down from these altitudes to the intermediate worlds behind ours, to the lesser godheads or genii, it still carries into them some power or some hint from above. And when it comes quite down to the material world and the life of man and the things of external Nature, it does not altogether get rid of the greater vision, the hieratic stamp, the spiritual seeing, and in most good work—except in moments of relaxation and a humorous or vivid play with the obvious—there is always something more in which the seeing presentation of life floats as in an immaterial atmosphere.

Also read:

The Way of the Indian Artist

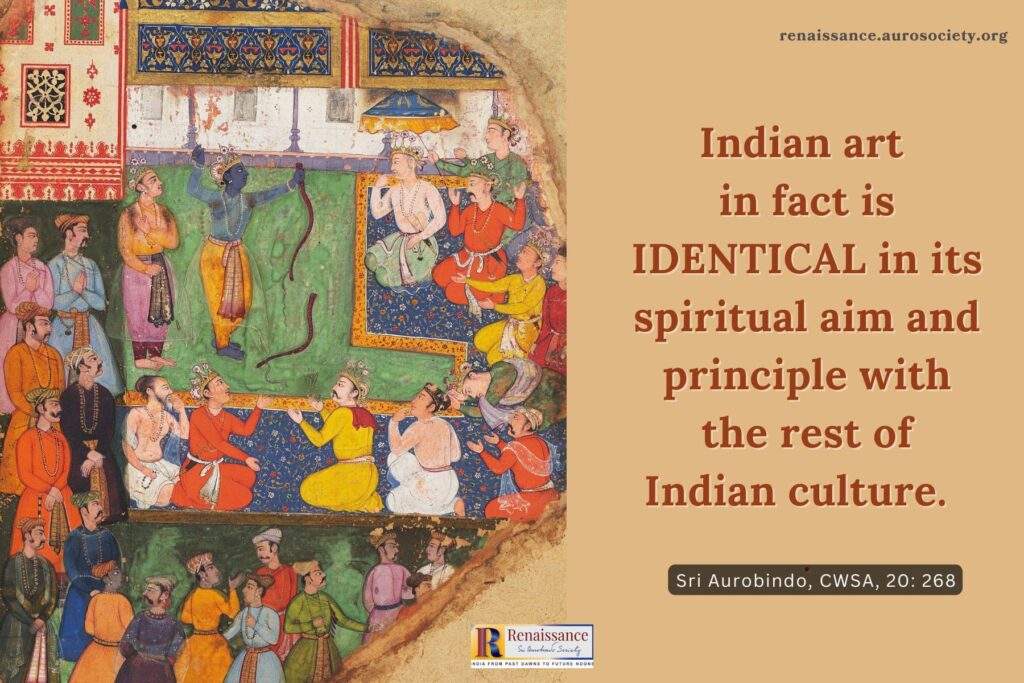

Life is seen in the self or in some suggestion of the infinite or of something beyond or there is at least a touch and influence of these which helps to shape the presentation. It is not that all Indian work realises this ideal; there is plenty no doubt that falls short, is lowered, ineffective or even debased, but it is the best and the most characteristic influence and execution which gives its tone to an art and by which we must judge. Indian art in fact is identical in its spiritual aim and principle with the rest of Indian culture.

The Characteristic Method of the Indian Artist

A seeing in the self accordingly becomes the characteristic method of the Indian artist and it is directly enjoined on him by the canon. He has to see first in his spiritual being the truth of the thing he must express and to create its form in his intuitive mind; he is not bound to look out first on outward life and Nature for his model, his authority, his rule, his teacher or his fountain of suggestions.

Why should he when it is something quite inward he has to bring out into expression? It is not an idea in the intellect, a mental imagination, an outward emotion on which he has to depend for his stimulants, but an idea, image, emotion of the spirit, and the mental equivalents are subordinate things for help in the transmission and give only a part of the colouring and the shape.

A material form, colour, line and design are his physical means of the expression, but in using them he is not bound to an imitation of Nature, but has to make the form and all else significant of his vision, and if that can only be done or can best be done by some modification, some pose, some touch or symbolic variation which is not found in physical Nature, he is at perfect liberty to use it, since truth to his vision, the unity of the thing he is seeing and expressing is his only business.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20. pp. 266-269

The Artist’s Contact with the Divine

“The Yogin’s aim in the Arts should not be a mere aesthetic, mental or vital gratification, but, seeing the Divine everywhere, worshipping it with a revelation of the meaning of its works, to express that One Divine in gods and men and creatures and objects.”

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 23, p. 142

Disciple’s Question

How can we “express that One Divine”?

The Mother’s Explanation

It depends on the subject one wants to express: gods, men or things.

When one paints a picture or composes music or writes poetry, each one has his own way of expression. Every painter, every musician, every poet, every sculptor has or ought to have a unique, personal contact with the Divine, and through the work which is his speciality, the art he has mastered, he must express this contact in his own way, with his own words, his own colours.

For himself, instead of copying the outer form of Nature, he takes these forms as the covering of something else, precisely of his relationship with the realities which are behind, deeper, and he tries to make them express that. Instead of merely imitating what he sees, he tries to make them speak of what is behind them, and it is this which makes all the difference between a living art and just a flat copy of Nature.

Mother contemplates a flower she is holding in her hand. It is the golden champak flower (Michelia champaka).

Have you noticed this flower?

It has twelve petals in three rows of four. We have called it “Supramental psychological perfection”.

I had never noticed that it had three rows: a small row like this, another one a little larger and a third one larger still. They are in gradations of four: four petals, four petals, four petals.

Well, if one indeed wants to see in the forms of Nature a symbolic expression, one can see a centre which is the supreme Truth, and a triple manifestation―because four indicates manifestation―in three superimposed worlds: the outermost―these are the largest petals, the lightest in colour―that is a physical world, then a vital world and a mental world, and then at the centre, the supramental Truth.

And you can discover all kinds of other analogies.

~ The Mother, CWM, Vol. 8, pp. 157-158

~ Design: Beloo Mehra