Volume VI, Issue 4

Author: Sri Aurobindo

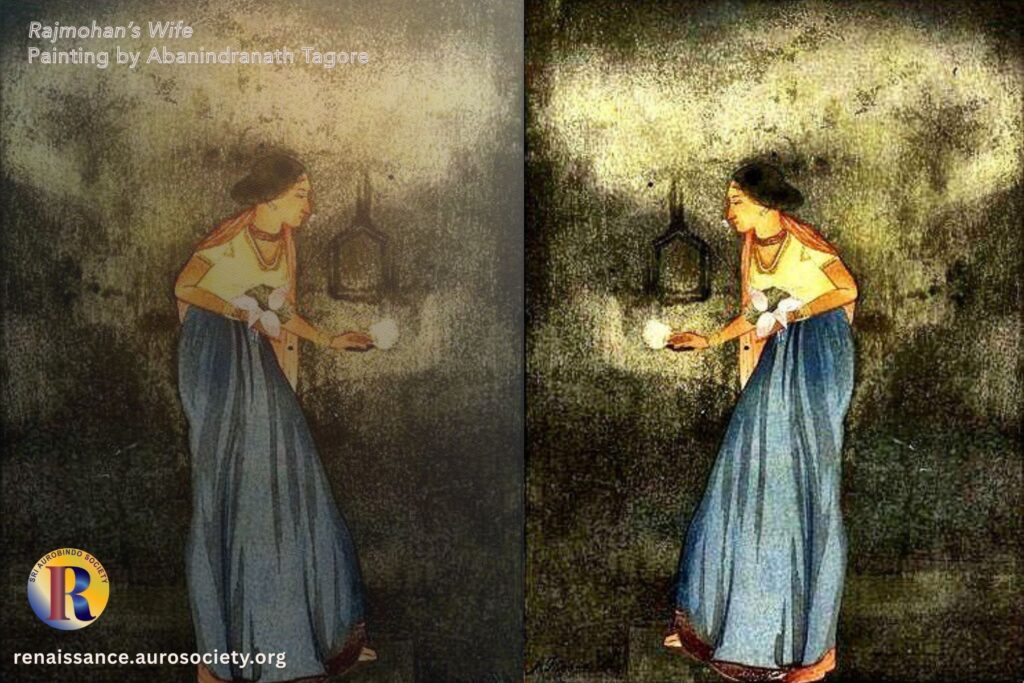

Editor’s Note: Sri Aurobindo, in his volume The Renaissance in India and Other Essays on Indian Culture, devotes a full essay on Indian sculpture (CWSA, Vol. 20, pp. 286-297). We find there an inspiring description of the profound intention and motive which guides Indian sculptural art, and also its deep and intimate connection with the spiritual and religious-philosophic vision that is at the source of all Indian cultural expressions.

For the Guiding Light feature we highlight some selections from that chapter and present them in two parts.

Profound Intention of Indian Sculptural Art

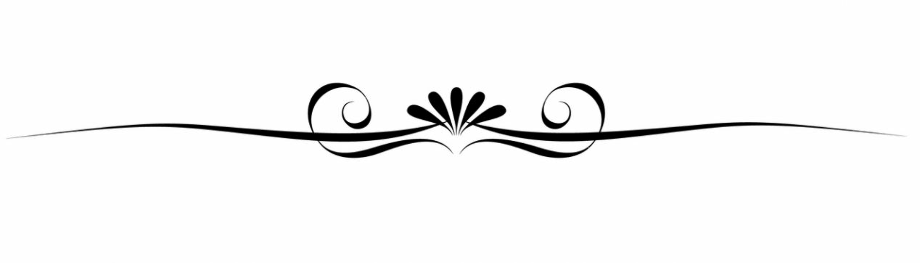

To appreciate our own artistic past at its right value we have to free ourselves from all subjection to a foreign outlook and see our sculpture and painting,… in the light of its own profound intention and greatness of spirit. When we so look at it, we shall be able to see that the sculpture of ancient and mediaeval India claims its place on the very highest levels of artistic achievement.

I do not know where we shall find a sculptural art of a more profound intention, a greater spirit, a more consistent skill of achievement. Inferior work there is, work that fails or succeeds only partially, but take it in its whole, in the long persistence of its excellence, in the number of its masterpieces, in the power with which it renders the soul and the mind of a people, and we shall be tempted to go further and claim for it a first place.

The art of sculpture has indeed flourished supremely only in ancient countries where it was conceived against its natural background and support, a great architecture. Egypt, Greece, India take the premier rank in this kind of creation. Mediaeval and modern Europe produced nothing of the same mastery, abundance and amplitude, while on the contrary in painting later Europe has done much and richly and with a prolonged and constantly renewed inspiration.

Different Kinds of Mentality Required for Sculpture and Painting

The difference arises from the different kind of mentality required by the two arts. The material in which we work makes its own peculiar demand on the creative spirit, lays down its own natural conditions,… and the art of making in stone or bronze calls for a cast of mind which the ancients had and the moderns have not or have had only in rare individuals, an artistic mind not too rapidly mobile and self-indulgent, not too much mastered by its own personality and emotion and the touches that excite and pass, but founded rather on some great basis of assured thought and vision, stable in temperament, fixed in its imagination on things that are firm and enduring.

One cannot trifle with ease in these sterner materials, one cannot even for long or with safety indulge in them in mere grace and external beauty or the more superficial, mobile and lightly attractive motives. The aesthetic self-indulgence which the soul of colour permits and even invites, the attraction of the mobile play of life to which line of brush, pen or pencil gives latitude, are here forbidden or, if to some extent achieved, only within a line of restraint to cross which is perilous and soon fatal. Here grand or profound motives are called for, a more or less penetrating spiritual vision or some sense of things eternal to base the creation.

The sculptural art is static, self-contained, necessarily firm, noble or severe and demands an aesthetic spirit capable of these qualities. A certain mobility of life and mastering grace of line can come in upon this basis, but if it entirely replaces the original dharma of the material, that means that the spirit of the statuette has come into the statue and we may be sure of an approaching decadence.

Spiritual Motive Essential for High Sculptural Art

Hellenic sculpture following this line passed from the greatness of Phidias through the soft self-indulgence of Praxiteles to its decline. A later Europe has failed for the most part in sculpture, in spite of some great work by individuals, an Angelo or a Rodin, because it played externally with stone and bronze, took them as a medium for the representation of life and could not find a sufficient basis of profound vision or spiritual motive.

In Egypt and in India, on the contrary, sculpture preserved its power of successful creation through several great ages. The earliest recently discovered work in India dates back to the fifth century B.C. and is already fully evolved with an evident history of consummate previous creation behind it, and the latest work of some high value comes down to within a few centuries from our own time. An assured history of two millenniums of accomplished sculptural creation is a rare and significant fact in the life of a people.

Connection between the Religious, Philosophical and the Aesthetic Mind

This greatness and continuity of Indian sculpture is due to the close connection between the religious and philosophical and the aesthetic mind of the people. Its survival into times not far from us was possible because of the survival of the cast of the antique mind in that philosophy and religion, a mind familiar with eternal things, capable of cosmic vision, having its roots of thought and seeing in the profundities of the soul, in the most intimate, pregnant and abiding experiences of the human spirit.

…What Greek sculpture expressed was fine, gracious and noble, but what it did not express and could not by the limitations of its canon hope to attempt, was considerable, was immense in possibility, was that spiritual depth and extension which the human mind needs for its larger and deeper self-experience. And just this is the greatness of Indian sculpture that it expresses in stone and bronze what the Greek aesthetic mind could not conceive or express and embodies it with a profound understanding of its right conditions and a native perfection.

Sculpture that Springs from Spiritual Realisation

The more ancient sculptural art of India embodies in visible form what the Upanishads threw out into inspired thought and the Mahabharata and Ramayana portrayed by the word in life. This sculpture like the architecture springs from spiritual realisation, and what it creates and expresses at its greatest is the spirit in form, the soul in body, this or that living soul power in the divine or the human, the universal and cosmic individualised in suggestion but not lost in individuality, the impersonal supporting a not too insistent play of personality, the abiding moments of the eternal, the presence, the idea, the power, the calm or potent delight of the spirit in its actions and creations.

And over all the art something of this intention broods and persists and is suggested even where it does not dominate the mind of the sculptor. And therefore as in the architecture so in the sculpture, we have to bring a different mind to this work, a different capacity of vision and response, we have to go deeper into ourselves to see than in the more outwardly imaginative art of Europe.

The Gods of Indian Sculpture

The Olympian gods of Phidias are magnified and uplifted human beings saved from a too human limitation by a certain divine calm of impersonality or universalised quality, divine type, guna; in other work we see heroes, athletes, feminine incarnations of beauty, calm and restrained embodiments of idea, action or emotion in the idealised beauty of the human figure.

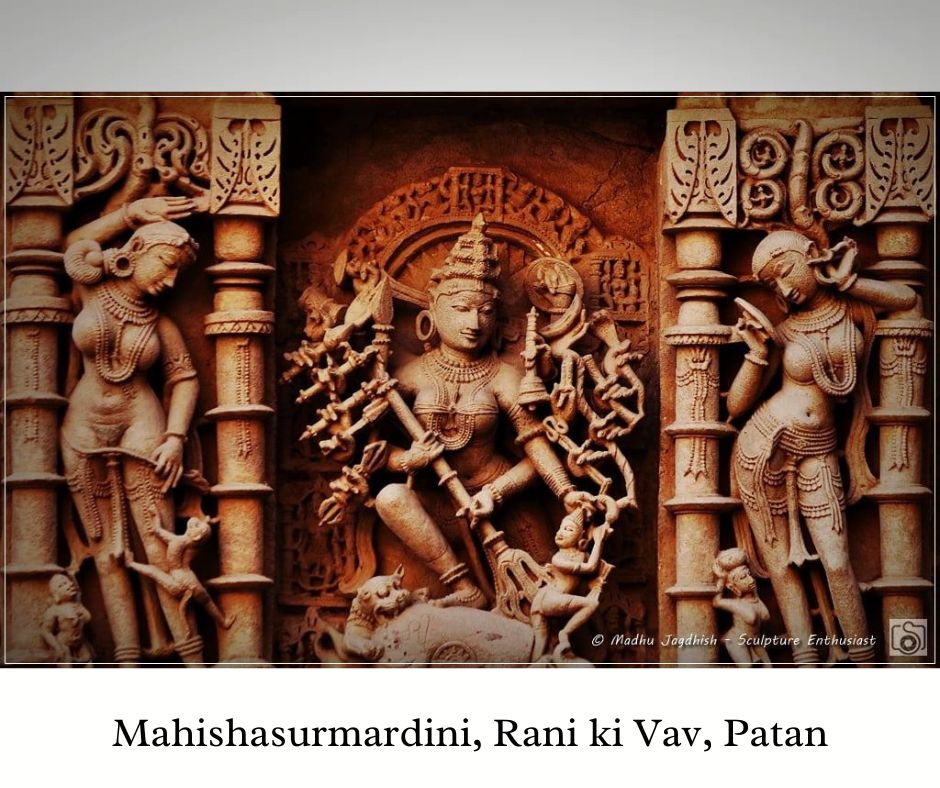

The gods of Indian sculpture are cosmic beings, embodiments of some great spiritual power, spiritual idea and action, inmost psychic significance, the human form a vehicle of this soul meaning, its outward means of self-expression; everything in the figure, every opportunity it gives, the face, the hands, the posture of the limbs, the poise and turn of the body, every accessory, has to be made instinct with the inner meaning, help it to emerge, carry out the rhythm of the total suggestion, and on the other hand everything is suppressed which would defeat this end, especially all that would mean an insistence on the merely vital or physical, outward or obvious suggestions of the human figure.

Not the ideal physical or emotional beauty, but the utmost spiritual beauty or significance of which the human form is capable, is the aim of this kind of creation. The divine self in us is its theme, the body made a form of the soul is its idea and its secret. And therefore in front of this art it is not enough to look at it and respond with the aesthetic eye and the imagination, but we must look also into the form for what it carries and even through and behind it to pursue the profound suggestion it gives into its own infinite.

Inner Aim and Vision of the Sculptor

…soul realisation is its method of creation and soul realisation must be the way of our response and understanding. And even with the figures of human beings or groups it is still a like inner aim and vision which governs the labour of the sculptor.

The statue of a king or a saint is not meant merely to give the idea of a king or saint or to portray some dramatic action or to be a character portrait in stone, but to embody rather a soul state or experience or deeper soul quality, as for instance, not the outward emotion, but the inner soul-side of rapt ecstasy of adoration and God-vision in the saint or the devotee before the presence of the worshipped deity.

This is the character of the task the Indian sculptor set before his effort and it is according to his success in that and not by the absence of something else, some quality or some intention foreign to his mind and contrary to his design, that we have to judge of his achievement and his labour.

Once we admit this standard, it is impossible to speak too highly of the profound intelligence of its conditions which was developed in Indian sculpture, of the skill with which its task was treated or of the consummate grandeur and beauty of its masterpieces. Take the great Buddhas—not the Gandharan, but the divine figures or groups in cave cathedral or temple, the best of the later southern bronzes…, the Kalasanhara image, the Natarajas. No greater or finer work, whether in conception or execution, has been done by the human hand and its greatness is increased by obeying a spiritualised aesthetic vision.

Buddha, Kalasanhara and Nataraja

The figure of the Buddha achieves the expression of the infinite in a finite image, and that is surely no mean or barbaric achievement, to embody the illimitable calm of Nirvana in a human form and visage.

The Kalasanhara Shiva is supreme not only by the majesty, power, calmly forceful control, dignity and kingship of existence which the whole spirit and pose of the figure visibly incarnates,—that is only half or less than half its achievement,—but much more by the concentrated divine passion of the spiritual overcoming of time and existence which the artist has succeeded in putting into eye and brow and mouth and every feature and has subtly supported by the contained suggestion, not emotional, but spiritual, of every part of the body of the godhead and the rhythm of his meaning which he has poured through the whole unity of this creation.

Or what of the marvellous genius and skill in the treatment of the cosmic movement and delight of the dance of Shiva, the success with which the posture of every limb is made to bring out the rhythm of the significance, the rapturous intensity and abandon of the movement itself and yet the just restraint in the intensity of motion, the subtle variation of each element of the single theme in the seizing idea of these master sculptors?

***

Image after image in the great temples or saved from the wreck of time shows the same grand traditional art and the genius which worked in that tradition and its many styles, the profound and firmly grasped spiritual idea, the consistent expression of it in every curve, line and mass, in hand and limb, in suggestive pose, in expressive rhythm,—it is an art which, understood in its own spirit, need fear no comparison with any other, ancient or modern, Hellenic or Egyptian, of the near or the far East or of the West in any of its creative ages.

Continued in Part 2

~ Design: Beloo Mehra