Volume VI, Issue 4

Author: Sri Aurobindo

Continued from Part 1

Spiritual Sensitiveness and Psychic Curiosity

The line and run and turn demanded by the Indian aesthetic sense are not the same as those demanded by the European. It would take too long to examine the detail of the difference which we find not only in sculpture, but in the other plastic arts and in music and even to a certain extent in literature, but on the whole we may say that the Indian mind moves on the spur of a spiritual sensitiveness and psychic curiosity, while the aesthetic curiosity of the European temperament is intellectual, vital, emotional and imaginative in that sense, and almost the whole strangeness of the Indian use of line and mass, ornament and proportion and rhythm arises from this difference.

The two minds live almost in different worlds, are either not looking at the same things or, even where they meet in the object, see it from a different level or surrounded by a different atmosphere, and we know what power the point of view or the medium of vision has to transform the object. And undoubtedly there is very ample ground for…complaint of the want of naturalism in most Indian sculpture.

Concern of the Indian Sculptor

The inspiration, the way of seeing is frankly not naturalistic, not, that is to say, the vivid, convincing and accurate, the graceful, beautiful or strong, or even the idealised or imaginative imitation of surface or terrestrial nature. The Indian sculptor is concerned with embodying spiritual experiences and impressions, not with recording or glorifying what is received by the physical senses.

He may start with suggestions from earthly and physical things, but he produces his work only after he has closed his eyes to the insistence of the physical circumstances, seen them in the psychic memory and transformed them within himself so as to bring out something other than their physical reality or their vital and intellectual significance. His eye sees the psychic line and turn of things and he replaces by them the material contours.

It is not surprising that such a method should produce results which are strange to the average Western mind and eye when these are not liberated by a broad and sympathetic culture. And what is strange to us, is naturally repugnant to our habitual mind and uncouth to our habitual sense, bizarre to our imaginative tradition and aesthetic training. We want what is familiar to the eye and obvious to the imagination and will not readily admit that there may be here another and perhaps greater beauty than that in the circle of which we are accustomed to live and take pleasure.

Application of the Psychic Vision to Human Form

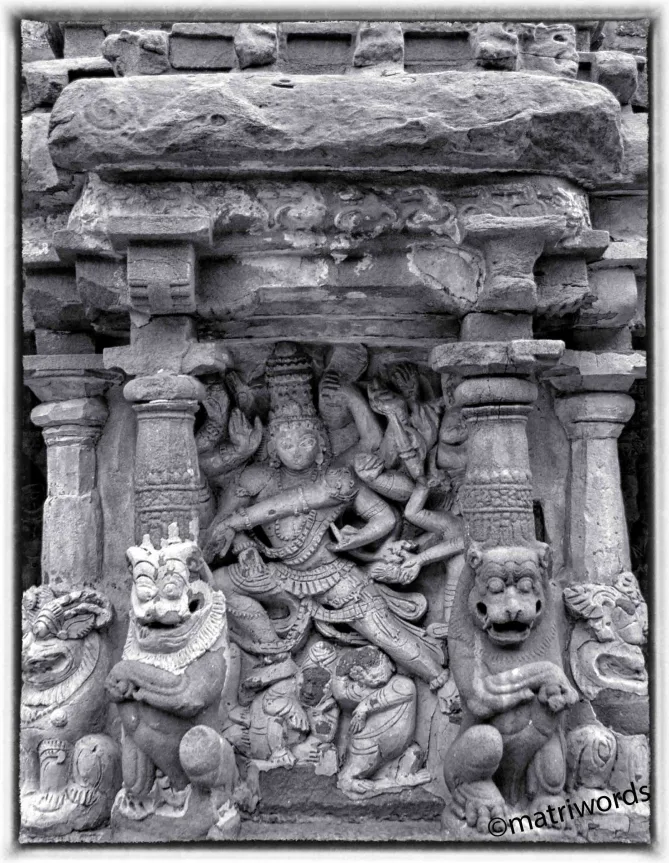

It seems to be especially the application of this psychic vision to the human form which offends these critics of Indian sculpture. There is the familiar objection to such features as the multiplication of the arms in the figures of gods and goddesses, the four, six, eight or ten arms of Shiva, the eighteen arms of Durga, because they are a monstrosity, a thing not in nature.

Now certainly a play of imagination of this kind would be out of place in the representation of a man or woman, because it would have no artistic or other meaning, but I cannot see why this freedom should be denied in the representation of cosmic beings like the Indian godheads.

The whole question is, first, whether it is an appropriate means of conveying a significance not otherwise to be represented with an equal power and force and, secondly, whether it is capable of artistic representation, a rhythm of artistic truth and unity which need not be that of physical nature. If not, then it is an ugliness and violence, but if these conditions are satisfied, the means are justified and I do not see that we have any right, faced with the perfection of the work, to raise a discordant clamour….

The same truth holds as to the Durga with her eighteen arms slaying the Asuras or the Shivas of the great Pallava creations where the lyrical beauty of the Natarajas is absent, but there is instead a great epical rhythm and grandeur. Art justifies its own means and here it does it with a supreme perfection. And as for the “contorted” postures of some figures, the same law holds.

To Express the Dreams and Truths of the Human Spirit

There is often a departure in this respect from the anatomical norm of the physical body or else—and that is a rather different thing—an emphasis more or less pronounced on an unusual pose of limbs or body, and the question then is whether it is done without sense or purpose, a mere clumsiness or an ugly exaggeration, or whether it rather serves some significance and establishes in the place of the normal physical metric of Nature another purposeful and successful artistic rhythm.

Art after all is not forbidden to deal with the unusual or to alter and overpass Nature, and it might almost be said that it has been doing little else since it began to serve the human imagination from its first grand epic exaggerations to the violences of modern romanticism and realism, from the high ages of Valmiki and Homer to the day of Hugo and Ibsen. The means matter, but less than the significance and the thing done and the power and beauty with which it expresses the dreams and truths of the human spirit.

Indian Artistic Treatment of the Human Figure

The whole question of the Indian artistic treatment of the human figure has to be understood in the light of its aesthetic purpose. It works with a certain intention and ideal, a general norm and standard which permits of a good many variations and from which too there are appropriate departures….

There are other things here than a repetition of hawk faces, wasp waists, thin legs and the rest of the ill-tempered caricature. …these old Indian artists knew the anatomy of the body well enough, as Indian science knew it, but chose to depart from it for their own purpose. It does not seem to me to matter much, since art is not anatomy, nor an artistic masterpiece necessarily a reproduction of physical fact or a lesson in natural science. I see no reason to regret the absence of telling studies in muscles, torsos, etc., for I cannot regard these things as having in themselves any essential artistic value.

The one important point is that the Indian artist had a perfect idea of proportion and rhythm and used them in certain styles with nobility and power, in others like the Javan, the Gauda or the southern bronzes with that or with a perfect grace added and often an intense and a lyrical sweetness.

The Ideal of a Divine and Subtle Body

The dignity and beauty of the human figure in the best Indian statues cannot be excelled, but what was sought and what was achieved was not an outward naturalistic, but a spiritual and a psychic beauty, and to achieve it the sculptor suppressed, and was entirely right in suppressing, the obtrusive material detail and aimed instead at purity of outline and fineness of feature. And into that outline, into that purity and fineness he was able to work whatever he chose, mass of force or delicacy of grace, a static dignity or a mighty strength or a restrained violence of movement or whatever served or helped his meaning.

A divine and subtle body was his ideal; and to a taste and imagination too blunt or realistic to conceive the truth and beauty of his idea, the ideal itself may well be a stumbling-block, a thing of offence. But the triumphs of art are not to be limited by the narrow prejudices of the natural realistic man; that triumphs and endures which appeals to the best, sadhu-sammatam, that is deepest and greatest which satisfies the profoundest souls and the most sensitive psychic imaginations.

Expression of the Spirit and Ideals of a Great Culture

Each manner of art has its own ideals, traditions, agreed conventions; for the ideas and forms of the creative spirit are many, though there is one ultimate basis. … Indian sculpture, Indian art in general follows its own ideal and traditions and these are unique in their character and quality.

It is the expression great as a whole through many centuries and ages of creation, supreme at its best, whether in rare early pre-Asokan, in Asokan or later work of the first heroic age or in the magnificent statues of the cave-cathedrals and Pallava and other southern temples or the noble, accomplished or gracious imaginations of Bengal, Nepal and Java through the after centuries or in the singular skill and delicacy of the bronze work of the southern religions, a self expression of the spirit and ideals of a great nation and a great culture which stands apart in the cast of its mind and qualities among the earth’s peoples, famed for its spiritual achievement, its deep philosophies and its religious spirit, its artistic taste, the richness of its poetic imagination, and not inferior once in its dealings with life and its social endeavour and political institutions.

Profound Interpretation of the Inner Soul

This sculpture is a singularly powerful, a seizing and profound interpretation in stone and bronze of the inner soul of that people. The nation, the culture failed for a time in life after a long greatness, as others failed before it and others will yet fail that now flourish; the creations of its mind have been arrested, this art like others has ceased or fallen into decay, but the thing from which it rose, the spiritual fire within still burns and in the renascence that is coming it may be that this great art too will revive, not saddled with the grave limitations of modern Western work in the kind, but vivified by the nobility of a new impulse and power of the ancient spiritual motive.

Let it recover, not limited by old forms, but undeterred by the cavillings of an alien mind, the sense of the grandeur and beauty and the inner significance of its past achievement; for in the continuity of its spiritual endeavour lies its best hope for the future.

Read Part 1

~ Design: Beloo Mehra