Volume II, Issue 3

Author: M. P. Pandit

Continued from PART 1

The Upanishads have been listed differently, by various authorities, in the order of their importance. But whatever the enumeration, the Isha or the Ishavasya—so called after the opening words of the texts— always occupied the pride of place at the head. This is mainly because it is the only Upanishad to form an integral part of a Samhita while the others belong to the Brahmanas or the Aranyakas. It is the 40th and final chapter of the Shukla Yajur Veda.

From the point of view of subject-matter also, the Isha Upanishad is unique. It addresses itself to the question of world-existence, the problem of harmonising human life and activity with the Reality of Immutable Brahman. The solution it finds is one of the most remarkable found by the ancient Indian mind. Its teaching is “the reconciliation, by the perception of essential Unity, of the apparently incompatible opposites, God and the World, Renunciation and Enjoyment, Action and internal Freedom, the One and the Many, Being and its Becomings, the passive divine Impersonality and the active divine Personality, the Knowledge and the Ignorance, the Becoming and the Not-Becoming, Life on earth and beyond and the supreme Immortality.” (CWSA, Vol. 17, p, 11)

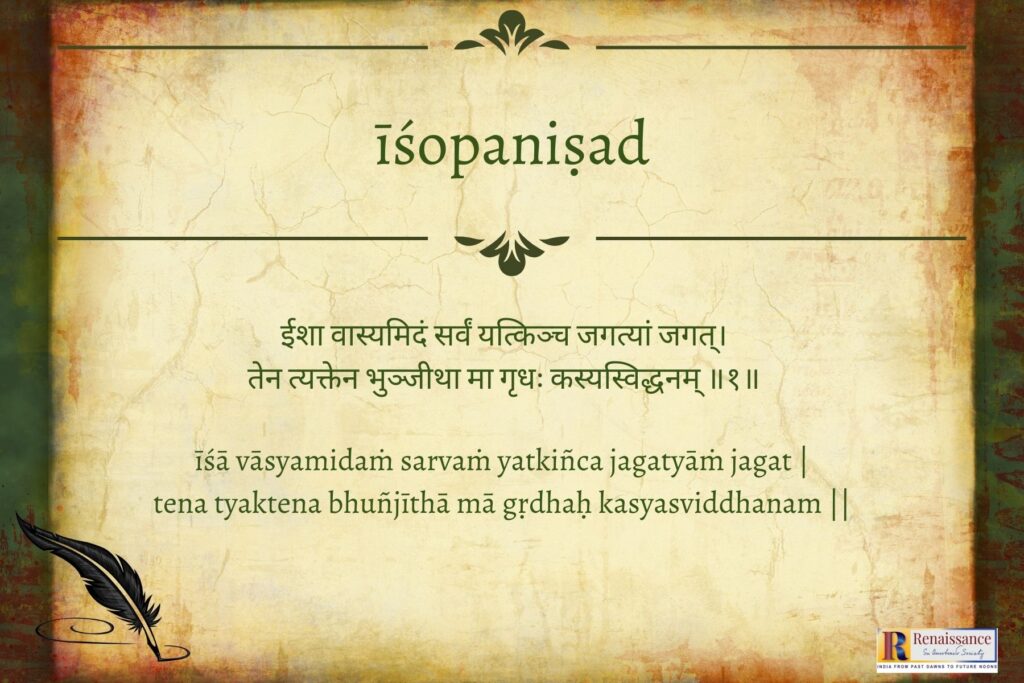

The very first lines announce the setting in which the key to the whole problem is found naturally:

ईशावास्यमिदं सर्वं यत् किञ्च जगत्यां जगत्।

तेन त्यक्तेन भुञ्जीथा मा गृधः कस्य स्विद्धनम्॥१॥

“All this is for habitation by the Lord, whatsoever is individual universe of movement in the universal motion. By that renounced thou shouldst enjoy; lust not after any man’s possession.” (CWSA, Vol. 17, p. 5)

Vasyam is here rendered in the sense of ‘to be inhabited’, ‘dwelt in’—root vas meaning to dwell. Acharya Shankara explains it to mean ‘to be clothed’, ‘to be enveloped’. Look not at this unreal world but at the reality of the pure Brahman by which it shall be covered: our sense of the world must disappear into the perception of the enveloping Reality. While this may suit the Adwaitic standpoint, Sri Aurobindo points out that it goes counter to the general spirit of the Upanishad which at every step reconciles the apparent opposites in manifestation.

The universe is a movement of the Spirit. It is a continuous unrolling of the Spirit in myriad forms which are so many currents of the Great Movement. Each form is a front, a shaping of the general stream in an individualised unit. Each one has the Whole behind, sustaining it, and thus constitutes a universe in itself. Wherefore this movement? It is meant, says the Upanishad, for the dwelling of the Spirit who has originated and cast out this extension. All is to provide a fitting abode for the Lord of All.

This world is a manifestation of God for his enjoyment. He has created it out of himself in joy and takes up his dwelling in it for a yet fuller joy. And this enjoyment implies, necessarily, enjoyment by all, by the many who constitute his manifestation. Yet, joy and happiness are not the normal features of the world. In fact, the opposite seems to be the rule. Why? It is because the many, the individuals move and act in complete ignorance of their true nature, their identity with the One Spirit informing and basing them, and through It with all the rest.

Each looks upon himself as distinct and different from the other and his outlook is governed by this sense of separativity, the ego which gives birth to Desire to affirm himself against others, snatch enjoyment for himself at the cost of others. This effort leads to friction, conflict and suffering. Man is lost in activity in this vain pursuit of happiness. True enjoyment comes naturally with the renunciation of this vitiating desire, the desire for separate self-affirmation and self-aggrandisement and an inner recognition and realisation of the truth of the identity of oneself with the soul within who is always the Lord and its unity with the Soul of All who is same in each.

Thus, we learn that the world is a movement of God; it has a purpose which is to provide a habitation for God for his enjoyment. The individual is a living term and front of this manifestation and should share in this enjoyment; but his ignorance of his true nature shuts him from this happiness and gives rise to the ego-sense of a separate self-living and. its consequent struggle and strife. This principle of Desire should be put behind if one is to participate in the Lord’s enjoyment. The individual must become aware of his soul, the true source of enjoyment and identify himself with this Lord of his individualised universe.

But to realise this identity with the soul within does not mean that he should withdraw from life without, the activity of the body and mind. On the contrary:

कुर्वन्नेवेह कर्माणि जिजीविषेत् शतं समाः।

एवं त्वयि नान्यथेतोऽस्ति न कर्म लिप्यते नरे॥२॥

“Doing verily, works in this world one should wish to live a hundred years. Thus it is in thee and not otherwise than this; action cleaves not to a man.” (CWSA, Vol. 17, p. 5)

He must, indeed, eva, do works[1]. He cannot but do that. No man can desist from activity; even what is called inactivity is a kind of action and has its own results. Even as the Lord has projected this world as the means of a certain fulfilment, the individual too has a self-fulfilment to achieve and he is to participate in this activity to that end.

One should live the full span of life, says the text, doing one’s part; the previous verse has laid down the right mode of action and life, viz., to renounce desire and participate in this Manifestation which is meant for the enjoyment of the one Lord of All, in All. Thus done, no action can bind the doer with the motivating desire, the executing energies or with the ensuing chain of consequences. That is the true law of living. For those who follow this Law there is joy and felicity. But for those who in their ignorance and egoism choose to ignore the truth and persist in their own false and ego-centred way of life the future is different:

असूर्या नाम ते लोका अन्धेन तमसावृताः।

तांस्ते प्रेत्याभिगच्छन्ति ये के चात्महनो जनाः॥३॥

“Sunless[2] are those worlds and enveloped in blind gloom where to all they in their passing hence resort who are slayers of their souls.”

(CWSA, Vol. 17, p. 6)

There are other worlds besides this material one in which we live. And when the physical body dies, the being of man goes to and through these other worlds of varying substances, of different kinds, obscure and illumined. The kind of world to which one is drawn depends upon the tendencies formed and the equipment wrought during the life in body on the earth.

They who have risen above the life of the senses, of preoccupation with bodily wants and pleasures, and have strived and achieved a progressive synthesis in themselves of higher knowledge, purity and luminous dynamism and peace—in a word, developed a soul-life—are naturally gravitated to like worlds of light and joy.

But those who have refused to listen to the call of the soul and have forced it to slog in the quagmires of inertia and falsehood or hover round and round in the blind circle of desire and passion, pleasure and pain—these, says the Upanishad, have to pass to worlds which are sunless, bereft of the light of the Sun of spiritual truth, worlds of Darkness.

If so, is movement, eternal movement the sole truth? Is it not rather that the Truth in the final sense lies in Stability, an Immutability? The Upanishad affirms both as truths of the Brahman, the Supreme Reality; both are poises of IT; each is relative to the other.

अनेजदेकं मनसो जवीयो नैनद्देवा आप्नुवन् पूर्वमर्षत्।

तद्धावतोऽन्यानत्येति तिष्ठत्तस्मिन्नपो मातरिश्वा दधाति॥४॥

“One unmoving that is swifter than Mind, That (he Gods reach not, for It progresses ever in front. That, standing, passes beyond others as they run. In That the Master of Life establishes the Waters.” (CWSA, Vol. 17, p. 6)

तदेजाति तन्नैजति तद् दूरे तद्वन्तिके।

तदन्तस्य सर्वस्य तदु सर्वस्यास्य बाह्यतः॥५॥

“That moves and That moves not That is far and the same is near; That is within all this and That also is outside all this.” (CWSA, Vol. 17, p. 7)

Notes

[1] Sri Aurobindo notes how unnatural is the interpretation by Shankara of the word karmani in two different ways in the same verse. In the first line karmani is taken to mean sacrifices and other religious acts which are expected to be performed by the ignorant for reaping fruits from good actions and averting the results of the evil; in the second line the word is taken as the opposite, evil deeds. The Acharya says that for those who do not aim at the realisation of atman and are content with the normal human life, doing the rituals is the only way of escaping the taint of evil deeds.

[2] Of the two readings asūrya, sunless, and asurya, titanic, undivine, Sri Aurobindo chooses the former in the light of the last four verses of the text. The prayer to the Sun in those verses “refers back in thought to the sunless worlds and their blind gloom, which are recalled in the ninth and twelfth verses. The sun and his rays are intimately connected in other Upanishads also with the worlds of Light and their natural opposite is the dark and sunless, not the Titanic worlds.” (Sri Aurobindo) In the Rig Veda, V.32.6, vritra the Hostile or anti-divine force is referred to as thriving in sunless darkness(असूर्ये तमसि ववृधानम्).

To be continued…

Read Part 1