Volume V, Issue 1

Author: Beloo Mehra

Sri Aurobindo speaks of the Veda as the first expression, the first form of the constant attempt of the Indian mind to seek a mystic knowledge. In Vedic poetry we find free use of image and myth. But this was not done as an imaginative indulgence. Rather the Rishis used these images and myths as living parables and symbols of things that were very real to them. The imagination itself ministered the greater realities than those which meet and hold the ordinary eye and mind, limited by only the external suggestions of life and the physical existence.

Even the smallest circumstances of the yajña, the sacrifice around which many of the Vedic hymns were written, carried deep symbolic and psychological significance. Sri Aurobindo gives an example of the invocation “Play, O Ray, and become towards us.” This suggests the leaping up and radiant play of the potent sacrificial flame on the physical altar. And it also symbolizes a similar psychical phenomenon, the manifestation of the saving flame of a divine power and light within us.

* * *

The rich spiritual experiences and realizations of the Vedic Rishis have been recorded through images and symbols. These can be interpreted at the spiritual, cosmic, psychological and physical levels.

The Veda, at the highest spiritual level, reveals the highest spiritual truth, powers and laws of the transcendent Reality. At the cosmic level it reveals laws and processes of the occult or cosmic forces in the play of their interaction and harmony. At the psychological level, it reveals the manifestations and workings of these cosmic forces in the psychological being of man. And finally, at the physical level, the Veda reveals the deeper laws of the physical nature. This complete or integral view shows that there is in this universe only one essential Law. And it repeats itself and works itself out differently at each level of the cosmos according to the energy and substance of that level.

New Flipbook:

The Language of the Veda

According to Sri Aurobindo, the Vedic poetry is in fact the beginning of a form of symbolic or figurative imagery for the poetic expression of spiritual experience. This imagery reappears constantly in later Indian writing. We see them in the figures of the Tantras and Puranas, and in the figures of the Vaishnava poets. There is a certain element of this even in the modern poetry of Tagore. We see similar imagery also in the poetry of some of the Sufi mystics.

What is it that the Vedic kavi aims to express through his poetry?

Sri Aurobindo explains that the poet has to express a spiritual and psychical knowledge and experience. And he cannot do it altogether or mainly in the more abstract language of the philosophical thinker. For he has to bring out, not merely the idea of his realization or experience, but its very life and most intimate touches, as vividly as possible.

The Rishi reveals in one way or another a whole world within him. And it is also a revelation of the quiet inner and spiritual significances of the world around him. These worlds also include godheads, powers, visions and experiences of planes of consciousness other than the one with which our normal minds are familiar.

And how does he express all this? Sri Aurobindo answers:

He uses or starts with the images taken from his own normal and outward life and that of humanity and from visible Nature, and though they do not of themselves actually express, yet obliges them to express by implication or to figure the spiritual and psychic idea and experience.

He takes them selecting freely his notation of images according to his insight or imagination and transmutes them into instruments of another significance and at the same time pours a direct spiritual meaning into the Nature and life to which they belong, applies outward figures to inner things and brings out their latent and inner spiritual or psychic significance into life’s outward figures and circumstances.

Or an outward figure nearest to the inward experience, its material counterpart, is taken throughout and used with such realism and consistency that while it indicates to those who possess it the spiritual experience, it means only the external thing to others,—just as the Vaishnava poetry of Bengal makes to the devout mind a physical and emotional image or suggestion of the love of the human soul for God, but to the profane is nothing but a sensuous and passionate love poetry hung conventionally round the traditional human-divine personalities of Krishna and Radha.

~ CWSA, Vol. 20, pp. 323-324

The Core of the Vedic Teaching

Sri Aurobindo summarizes this in a few key passages.

The Veda tells us that there is a Supreme Reality, a World or a Home of Truth, sadanam ṛtasya. And that there is a plane of consciousness where all is the Truth, the Right, the Vast, satyam ṛtaṁ bṛhat. In contrast to that there is an inferior truth here of THIS world. This world is mixed with much falsehood and error, anṛtasya bhūreḥ.

The Vedic Rishis saw that there are many worlds between these two — up to the Home of Truth. We have to find the path to this Great Heaven, the Home of Truth. And it must be the path of Truth, ṛtasya panthāḥ, the way of the gods.

Another key Vedic realisation is that the Self-luminous Reality is Essentially One: ekam sat or tad ekam.

The seers worshipped this One Reality in the image of the Sun, Surya, One existent. And they called him by various names, Indra, Agni, Yama, Matarishvan, etc. This is from the famous verse from RgVeda, 1.164.46 where we hear the Rishi singing ekam sat vipra bahudha vadanti.

The aspirant, the Aryan must walk on the path of the Truth, ṛtasya panthāḥ. But the powers of Darkness which conceal or rob us of the Light, obstruct the path. These powers exist because of the mixing of truth and falsehood in this lower triple world of physical, vital and mental existence.

Human life is a battle between the Powers of Light and Truth and the Powers of Darkness and Falsehood. The Vedic Rishis tell us that this battle was first fought by our forefathers, pitaro manushyah, and the divine Angirasas. These forefathers had attained a great victory. And we can also attain this by following the path of tapasyā our forefathers have hewn for us. But it is important to note that this path is not of renunciation of life but of self-giving and surrender.

READ:

The Angirasa Legend in the Veda

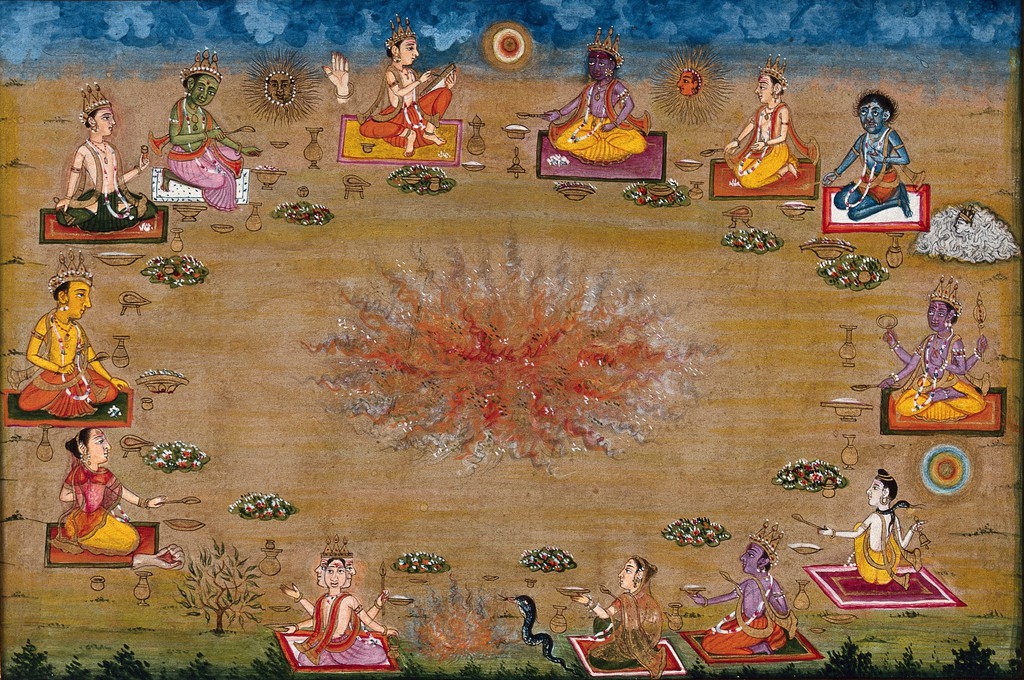

Man can establish Truth and Light within him and attain victory over Darkness and Falsehood. This requires constant invocation of the Divine powers through sacrifice, yajña, which leads to the ‘birth of the gods’ within. The yajña, or sacrifice is essentially a pilgrimage, “a travel towards the Gods.” We make this journey with Agni. Agni is the inner Flame or Conscious Will or Aspiration, as “our path-finder and leader.” (Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 16, p. 20).

This is the essential Vedic teaching which forms the core of Sanatana Dharma and Indian spiritual culture.

***

Yajña, the Original Creative Act

There is a deep inner psychological and occult meaning to the yajña. And it is essential to our understanding of the full Vedic vision. Yajña is also at the foundation of Indian cultural and sociological vision of life and its true aim and meaning.

Yajña is fundamentally the Original Creative Act of the Supreme, which Sri Aurobindo calls as Involution. It is through a cosmic sacrifice that the entire creative activity begins, says the Purusha Sūkta X.90 of Rig Veda.

Involution is thus the process of Supreme Reality becoming causal, subtle, and the gross universe; becoming the gods, earth and heaven, life and matter, the sun, moon and stars, animals and men. It is the process by which the Indivisible Unity of the Spirit becomes and involves itself in its exact opposite. That opposite is the infinite fragmentation of Matter.

As the Supreme Reality descends, at every stage there is a gradual loss of consciousness of Unity in the outer form. This gives rise to the Multiplicity through a process of voluntary self-limitation of the spirit. At the last stage, when Spirit becomes Matter, the loss becomes almost total.

But this loss of consciousness of Unity is only in the outer form. It is not at the level of the Spirit.

This is why we say that there is Divinity in Matter as well, perfectly veiled, waiting to be released. At the deeper level, the unity of the Being, the Purusha, is secretly present in every level of descent. And it is that which upholds and guides the whole process. In the causal state of the world, it is known as prajña. It is known in the subtle state as hiranyagarbha, and in the gross as virāt.

So here we have one half of the big picture of the Indian Vision of Reality. This half speaks of the One becoming Many, and of the Supreme Reality or the Supreme Being secretly hidden in each and every aspect of His manifestation.

***

Evolution is the other half of the story.

Evolution again is a yajña, a sacrifice done with the aim of reuniting with the Supreme Source, the Spirit which has become all worlds including the world of matter.

If the creative involution proceeds by a gradual loss and veiling of the consciousness of Unity in the individual forms through the limiting mechanism of consciousness, the sacrifice of evolution proceeds by a gradual rediscovery of the conscious Unity of the Spirit through the consequent increase or expansion of consciousness.

The essential movement of this evolutionary sacrifice is the denial of ego through an act of self-giving to the Universal and Transcendent Divine and its powers, the gods. The Veda tells us that in a cosmic order governed by the laws of unity and interdependence, the only right path towards evolutionary progress is through mutual self-giving or sacrifice.

The human aspirant sacrifices his triple lower nature, invites the devas, the gods, to be born within him. And the gods in turn uplift the human soul so that it may someday be released out of the Unconsciousness to Consciousness and finally into the Superconsciousness.

READ:

The Gods and Goddesses of the Veda

In this Issue

We explored the theme of Yoga of Indian Nation in the previous issue. It made sense now to do a deep dive into the soul of India, the Sanatana Dharma. The Veda, Sri Aurobindo tells us, is the bed-rock of Indian civilisation, and is the creation of an early intuitive and symbolic mentality. To the Vedic Rishis, the Veda was the Word discovering the Truth and clothing in image and symbol the mystic significances of life.

We begin with Sri Aurobindo’s summary of the deeper symbolism behind the legend of Angirasa Rishis from the Rig Veda. Here we learn about Vedic symbolism, about who or what is an Aryan, the true meaning of sacrifice, the ignorant reading of Aryan versus Dravidian divide in the Veda, and more. Kireet Joshi helps us go deeper into the Legend of the Lost Cows and of Angirasa Rishis.

Of Dogs, Gods and Elements: Symbolism in the Upanishads features excerpts from one Nolini Kanta Gupta’s longer essays. The focus here is on three aspects – the Five Elements, Triple Agni and Number of Gods.

* * *

Deva and Asura in the Bhagavad Gita features an excerpt from Sri Aurobindo’s Essays on the Gita. Here he gives a deeper psycho-spiritual understanding of Daivic and Asuric natures as described in Chapter 16 of the Bhagavad Gita. He further connects it with the ancient symbolism found in the Veda and speaks of the evolution of the soul in Nature as an adventure in its journey to the Divine.

We continue our exploration of symbolism in Sanatana Dharma by taking up a study of Savitri. Under the poem’s title, Sri Aurobindo gave a brief description “A Legend and a Symbol”. What is this legend? And what does this epic poem of Sri Aurobindo symbolize? To explore this, we begin a series Sri Aurobindo’s Savitri and Vyasa’s Savitri by Mangesh Nadkarni.

Of Pratīka and Pratimā: Why Do We Need Images and Symbols highlights three excerpts from Swami Vivekananda’s addresses on Bhakti Yoga. He speaks of the significance and the symbolism of images and forms for a devotee. A 2-part article by Beloo Mehra titled The Gods and Goddesses of the Veda summarizes Sri Aurobindo’s explanations of the deeper symbolism of some of the prominent Vedic deities.

In Daksha and Kali – Decoding the Symbols, Pradip Bhattacharya describes the deep symbolism behind the story of Daksha Prajapati’s head being severed, and his acquiring the head of a goat. M. S. Srinivasan in Vaishnava Symbolism and the Future of Symbols speaks of the symbolism hidden in one of the most delightful and profound aphorisms of Sri Aurobindo.

* * *

The elaborate practices of temple worship and mūrti puja are important means to bring the masses into the real temple of the spirit, says Sri Aurobindo. But these outer practices are given a psycho-emotional sense and direction which is open to the heart and imagination of the ordinary man. In The Inner Truth of Mūrti Pūjā Narendra Murty explains the deeper symbolism behind the mūrti pūjā. He goes into the symbolism hidden in the specific form of Ma Saraswati in a follow-up piece titled Reverential Pranāms to Vāgdevi Saraswati.

In our ongoing series The Upanishads Elucidated, we feature a new story by Lopa Mukherjee titled ‘The Seekers of Light‘. The key characters in the story are the children of four different kinds of light, Soma, Agni, Vajra and Surya.

As always, we offer this work at the lotus feet of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother.

In gratitude,

Beloo Mehra (for Renaissance Editorial Team)

~ Design: Beloo Mehra