Volume II, Issue 4

Author: Nirodbran

Editor’s Note: This talk given by Nirodbaran on June 12, 1970 at Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education was first published in Mother India. It was later compiled with several other talks of Amal Kiran in a book titled ‘Light and Laughter—Some Talks at Pondicherry’ published by Clear Ray Trust, 1972, pp. 70-76.

A most divine nobility and a perfectly sincere humility are the key highlights of the adorable personality of Sri Aurobindo which we see presented in this wonderful narration by Nirodbaran. One is reminded of the description Sri Aurobindo once gave of an Aryan gentleman. India’s rebirth and regeneration requires such character, such nobility in our youth; our national education must work toward this goal.

DON’T MISS: Humility and Aryan Character

PART 1

Friends, some of you at least must have been amused, others intrigued by the title of today’s talk. Some of you may even smell some irreverence because we have been accustomed to hear of Sri Aurobindo as the Lord of Yoga, as the supreme Poet, and the greatest Philosopher — to talk of him as a perfect gentleman is rather to bring him down to our own level, because we also claim to be some sort of gentlemen. I was told that the Mother was amused to hear of this title, but I throw the whole responsibility or irresponsibility of it on the Mother’s shoulders, because it was she herself who in a piquant situation remarked: “Sri Aurobindo is a perfect gentleman, I am not a gentleman.”

Well, it came as a shot from a cross-bow. We laughed at this outburst of temper, being familiar with her strangely changing moods, but still at this off-hand remark of hers, I was somewhat taken aback, and it made me think a bit. Earlier I had read — and most of you, students, teachers and professors must have read too — the celebrated piece by J.H. Newman on “A Gentleman”. When I read it, I thought it was something Utopian which could not be found in this world of ours — Newman’s description seemed unrealisable.

And when the Mother brought into our view Sri Aurobindo as the example of a perfect gentleman, I thought: “Yes, if there is anyone in the world who can be styled a perfect gentleman, it is Sri Aurobindo!” Now, for those of you who are not familiar with this passage, I shall read out some extracts, so that you may be able to see why I make this seemingly exaggerated statement.

Well, in the very first sentence, we find almost the quintessential character of a gentleman. Newman says:

“It is almost a definition of a gentleman to say he is one who never inflicts pain…. He is mainly occupied in merely removing the obstacles which hinder the free and unembarrassed action of those about him; and he concurs with their movements rather than take the initiative himself.”

In the Gita it is said, if I remember correctly, that a yogi never begins anything. Then —

“the true gentleman in like manner carefully avoids whatever may cause ajar or a jolt in the minds of those with whom he is cast; all clashing of opinion, or collision of feeling, all restraint or suspicion or gloom or resentment; his great concern being to make everyone at their ease and at home… he guards against unreasonable allusions, or topics which may irritate… he is seldom prominent in conversation… he never speaks of himself except when compelled, never defends himself by a mere retort, he has no ear for slander or gossip; he is never mean or little in disputes, never takes unfair advantage, never mistakes personalities or sharp sayings for arguments….

He has too much good sense to be affronted at insults, he is too well employed to remember injuries, and too indolent to bear malice. He is patient, forbearing, and resigned, on philosophical principles.”

I think this is enough to give you some idea of what a true gentleman is like. From the description that I shall try to put before you, you will be able to judge for yourself how much this passage is applicable to Sri Aurobindo. For my part, I can say — correlating these two — that in every fibre of his being Sri Aurobindo was a perfect gentleman.

I have chosen this subject because the others are beyond me, and on this one I can speak with some authority because, as most of you know, some of us had the great good fortune to come close to him, to see him face to face, to touch him, even to breathe him (but not to taste him!) — a subject about which I may claim, not egoistically, to have some confidence.

But before I plunge into it, let us go back a little and see whether Sri Aurobindo the gentleman was also a “gentle boy”.

Very little is known of his childhood, of his youth, as a matter of fact of his whole life. You know he has said that his life has not been on the surface. It has been shrouded in deep mystery, except when he chose to lift up the veil now and then — that’s all.

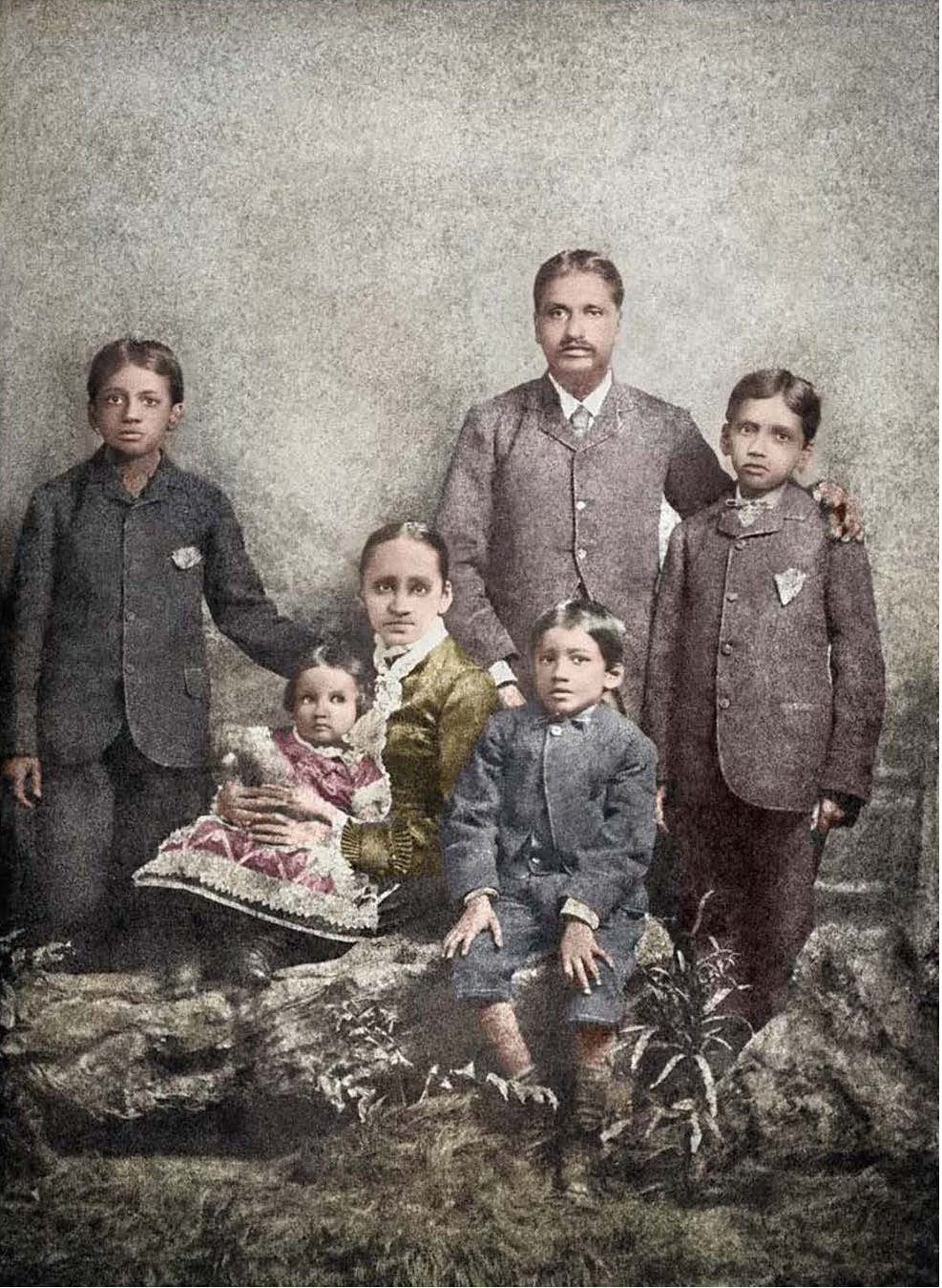

Now about his childhood. It was in 1956 or so that our artist sadhak, Pramode Chatterji, made a painting from Sri Aurobindo’s boyhood photograph, and brought it to the Mother. We were there sitting by her side. The Mother remarked (as I noted down at the time, not knowing that it would be used today): “You have caught something of the spontaneity and freshness of the nature and something candid with which he came into this world. His inner being was on the surface. He knew nothing of this world.” So that was an authoritative statement from the Mother. Another statement we have from his eldest brother, that he was a very nice and gentle boy except that he could be very obstinate.

Then what about the period of his youth in England? At the beginning, the brothers were very comfortable, affluent, but suddenly something went amiss: they found themselves in great penury. All the three brothers were almost stranded; the father for some mysterious reason stopped their allowances. … He took it calmly, quietly, in spite of 2 or 3 hard years, missing a square meal, living on some sandwiches, 3 cups of tea, some sausages, and in the cold climate of London without sufficient warm clothing.

But, as he has written to me, poverty was no terror for him, nor an incentive. He said that I was talking like Samuel Smiles! Then he failed in the I.C.S. riding test; he did it, as you know, deliberately by remaining absent as if by a tangle of unavoidable circumstances: in order not to hurt his hopeful father, not to inflict any pain on him, he had to resort to a trick.

[…]

At Cambridge, his tutor took upon himself, coming to know of the strained circumstances of his pupil, to write to the father in a somewhat cold tone, that the son was running the danger of being hauled to the court failing to pay up some arrears. The father at once sent the remittances but wrote an admonishing letter to his son, Aurobindo, that he was too extravagant! Sri Aurobindo said to us, smiling: “When we had not even one sufficient meal a day, where was the question of being extravagant?”

But he had no feeling of resentment or bitterness towards his father; whenever he spoke of him it was always with affection and tenderness.

Then we come to the Baroda period. There again we know very little except that he knew nothing about money. He said to us: “Yes, the Maharaja offered me a job saying he would pay Rs. 200. My brothers accepted, for they knew no better than I; and the Maharaja bragged that he had bagged an I.C.S. for Rs. 200!” However, Sri Aurobindo left behind a reputation of fair play, sincerity, honesty; he was loved by his students and all those who came in contact with him, though he wasn’t a social man at all.

He had a few chosen friends, lived a very simple life, and yet he could command the respect and honour of almost all the people there, high or low, with whom he came in touch or who heard his name. Even the Maharaja of Baroda held him in high esteem. But Sri Aurobindo showed his mettle once. The Maharaja issued a circular that all the officers must attend office on Sundays and even on holidays. Sri Aurobindo didn’t go. Then the Maharaja wanted to fine him. Sri Aurobindo said: “Let him fine as much as he likes, I am not going.” The Maharaja cooled down! He saw that Sri Aurobindo couldn’t be bent down by such threats.

The most revelatory remark of the period, that has come to us, was from his Bengali tutor, Dinendranath Roy, who, I suppose, was the first to say, because he lived closely with Sri Aurobindo: “Aurobindo is not a man, he is a god.”

Next he comes to Calcutta, to the political field which, you know, is not much better today, or is perhaps worse. Sri Aurobindo said to us, quoting C.R. Das’s opinion that “the political field is a rendezvous of the worst kind of criminals”; and that field, when Sri Aurobindo worked in it, he raised to a level of sincerity and integrity, at least in his own example, even if others didn’t always follow. He shunned crookedness, duplicity, lust for power and all the other vices of political life.

His ‘soul was like a star and dwelt apart’[i]. He raised the political consciousness of at least some people to his own level and he did it all because he was through and through sincere. “Sincerity,” Carlyle has said, “is the greatest virtue of a great man”. All of us know very well the Mother’s emphasis on sincerity. There is a line in Savitri referring to Savitri herself, which can be as well applied to Sri Aurobindo by a change of gender:

His mind, a sea of white sincerity,

Passionate in flow, had not one turbid wave. (p. 15)

In all the political disputes and negotiations, some of which are reflected in his speeches, there was never a tinge of meanness, duplicity or crookedness, that is so common, even so much courted by the politicians.

Thus he acquired the esteem of all and sundry, friends and foes. Students loved him, the young revolutionaries adored him, and all the rest respected him for his integrity, for his sincerity, for his self-sacrifice.

Also, there are one or two instances of his domestic life which will be illuminating. His younger brother Barin writes that when they were living together in Calcutta their sister Sarojini used to complain to Sri Aurobindo about the misbehaviour, the rude conduct, of the cook. Sri Aurobindo paid no heed, he kept quiet; finally Sarojini applied her ‘brahmastra’ and began to weep.

Now Sri Aurobindo had to do something; he called for the servant; everybody was waiting for something to happen. Addressing the servant he said, “Well, it seems you are behaving rudely. Don’t do it again.” That was all, and all those people were sorely disappointed. The cook went away smiling.

The second instance. Political leaders had come to meet Sri Aurobindo. He wanted to go and meet them, he saw that his slippers were missing. What had happend? His ‘mashi’ had the habit of putting on his slippers and knocking about. Sri Aurobindo called out, “Mashi, Mashi, people have come to see me; bring me back my slippers!”

There is an instance, too, from his jail life. He was living for a time with all the young prisoners in one cell, and pandemonium was let loose: songs, dancing, shouting. But Sri Aurobindo was most unconcerned with what was going on there. He was absorbed in his own sadhana, in one corner. One day those youngsters sat together and began to discuss a very momentous affair:

“Why does Aurobindo babu’s hair shine so much? Where does he get oil from? We don’t get a single drop!”

A great problem was to be solved. But how? They said someone could go and ask him, but nobody dared to. Then a young chap of 16 or 17 said: “I’ll go.” He went and asked:

“Sir, your hair is shining so much; will you tell us where you get oil from?”

Sri Aurobindo placed his hand on his shoulder and very calmly and softly said: “Oil, my boy? I don’t use any.”

“But your hair is shining”

“Yes, it is shining as a result of my practice of Yoga.”

The boy went back satisfied.

In all these examples you see how far he was a gentleman. I don’t need to multiply instances. I can say, again slightly adapting a verse from Savitri:

All in him pointed to a nobler kind. (p. 14)

Notes

[i] Reference to a line by William Wordsworth, from his poem titled ‘London 1802’.

Continued in Part 2 . . .

~ Design: Beloo Mehra