Continued from PART 3

Secular Legends

We have so far looked at the politically significant parts of the Mahabharata. But the epic also includes the worlds of religion, philosophy and didacticism, as well as myths and legends. Sri Aurobindo may have found all this rather overabundant, but his critical instinct remained undaunted and he found that imbedded in this vast mass was a group of secular Hindu legends that carried immense poetic possibilities. Defending these legends, he wrote to Manmohan Ghose:

My point is that the puerility is no essential part of them but lies in their presentment, and that presentment again is characteristic of the Hindu spirit not in its best and most self-realising epochs. They were written in an age of decline, and their present form is the result of a literary accident.

~ CWSA, Vol. 36, p. 127

The Mahabharata of Vyasa, originally an epic of 24,000 verses, afterwards enlarged by a redacting poet, was finally submerged in a vast mass of inferior accretions, the work often of a tasteless age and unskilful hands.

The sublime core of the legends lay concealed behind the accretions.

And despite several great Indian writers taking up the legends for rejuvenation as poetry, drama and narrative fiction, an immense treasure-trove still remained confined within the stretches of Vyasa’s epic. Hence, then, Sri Aurobindo’s exhortation:

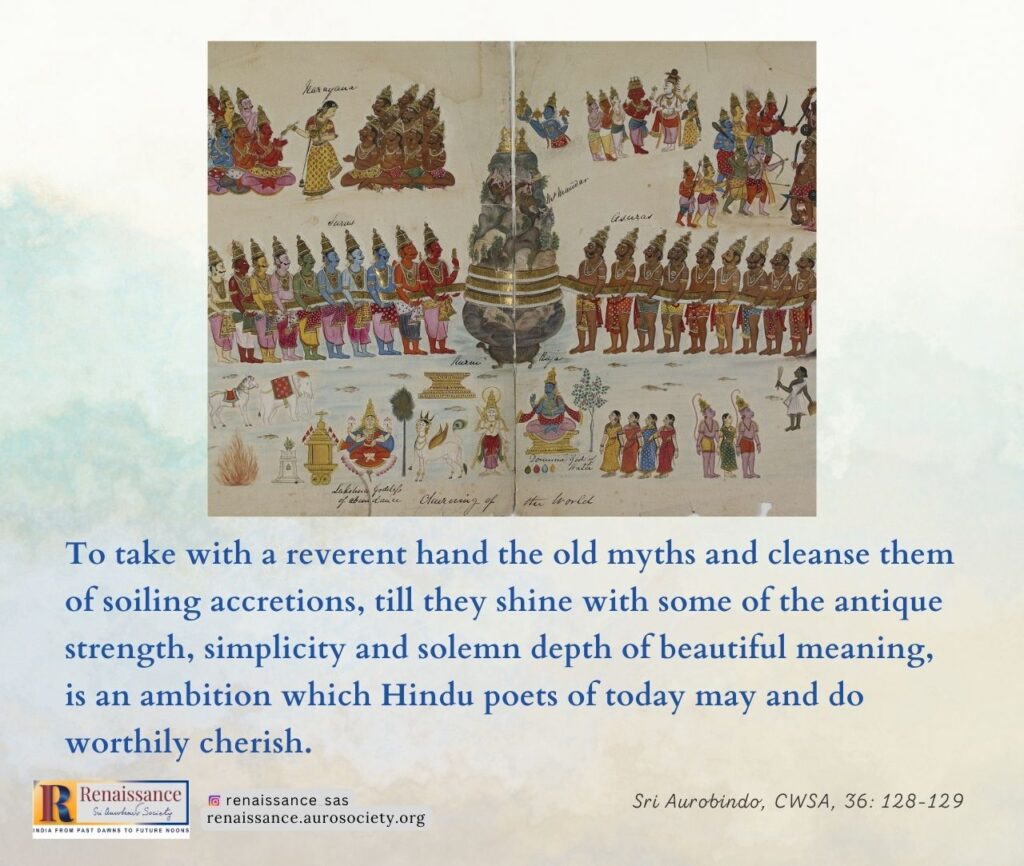

To take with a reverent hand the old myths and cleanse them of soiling accretions, till they shine with some of the antique strength, simplicity and solemn depth of beautiful meaning, is an ambition which Hindu poets of today may and do worthily cherish.

~ CWSA, Vol. 36, pp. 128-129

Sri Aurobindo himself was to do this in a large way.

He began with the legends of Nala, Chitrangada and Uloupy. None of these, however, was completed, but already we gain some idea of Sri Aurobindo’s blank verse that seeks to transform the seed-ideas in the Mahabharata into full-scale narrative poems. Romantic sensuousness envelopes the tales as with a silvery gauze.

Other names from the Mahabharata that led Sri Aurobindo to write shorter poems were Mandavya and Marcundeya. He also took up the tale of Ruru and Pramadvura which occurs in the Adi Parva (cantos 8 and 9) of the Mahabharata and transformed it into the splendidly articulate narrative poem, Love and Death.

Vyasa’s tale is brief. Bhrigu’s son, Chyavana, became the father of Pramati. Pramati married Kritasi and gave birth to Ruru who was to be famous for his austerities. He fell in love with Rishi Sthulakesa’s foster-daughter, Pramadvura, which means ‘the best among women’ (Pramada = woman; vara = best). On the eve of the marriage the girl dies of snake-bite. Through the help of Pramadvura’s Gandharva father, Ruru exchanges half his life for her, and Pramadvura is restored to life.

The story had such a strong impact on Sri Aurobindo that he wrote the 1000 lines of his version “in a white heat of inspiration during fourteen days of continuous writing — in the morning of course. . . ” (CWSA, Vol. 27, p. 220). The passages had come to him effortlessly, and indeed language never seems to fail whether he is describing love or death, the pleasure-grounds of love or the palace-mansions of death.

Sri Aurobindo also made a few important changes.

The name of Pramadvura was changed to Priyumvada as the latter was “more manageable to the English tongue” (CWSA, Vol. 2, p. 142). Whereas Ruru and Pramadvura are only betrothed in the original legend, Sri Aurobindo makes them newlyweds. And the opening movement of Love and Death is about their loving togetherness, a change that eliminates the need for cumbersome dramatis personae and makes Ruru’s loss sharper as he has now tasted the bliss of wedded life with Priyumvada.

On the very day he tells himself that this ecstasy will be there always, tragedy strikes the couple:

He saw a brilliant flash of coils evade

~ CWSA, Vol. 2, pp. 116-117

The sunlight, and with hateful gorgeous hood

Darted into green safety, hissing death.

As the ladies of the forest come to the girl to prepare the body for the final journey, Ruru wanders into the forest. His silent sorrow frightens the gods. On their request, an Aśvattha tree bears Ruru’s curse, and one half of it is blasted. Universal Love now comes to him as Kama, a golden boy. He can do everything but checkmate with Death. And Death is unmoved by gifts, except perhaps by an offering of life. Who will dare to make such a sacrifice ? But Ruru is willing:

For we shall live not fearing death, nor feel

~ CWSA, Vol. 2, p. 128

As others yearning over the loved at night

When the lamp flickers, sudden chills of dread

Terrible; nor at short absence agonise,

Wrestling with mad imagination. Us

Serenely when the darkening shadow comes,

One common sob shall end and soul clasp soul,

Not even the possibility of becoming a great Rishi “divine with age” can deflect Ruru from his choice. Yama accedes to the request and Ruru returns to the warm earth and a living Priyumvada.

Love and Death clearly shows the influence of the Hellenic culture on Sri Aurobindo’s poetry.

The legend of Orpheus and Euridyce no doubt inspired Sri Aurobindo to make Ruru go in person to Pātala to get back Priyumvada’s life. Nevertheless, Love and Death is an epyllion in its own right, transcending its Mahabharata origins and Hellenic dimensions. In fact, Yama is referred to as Hades.

The tales of Nala, Chitrangada and Ruru are about the separation of wedded couples and their coming together later on. The solutions suggested were not quite satisfying to Sri Aurobindo’s enquiring mind. Hence his final choice of the Savitri legend from the Mahabharata. It was as though Vyasa himself was one with Sri Aurobindo’s researches and re-creations and vouchsafed the modern Yogi his divine epic vision to render into English the most wonderful secular legend from India’s hoary past.