Volume VI, Issue 4

Author: Narendra Murty

Editor’s Note: This photo essay takes the reader high up in Spiti valley near the border of Tibet. It gives a peek into a Buddhist monastery which is known as the ‘Ajanta of the Himalayas’.

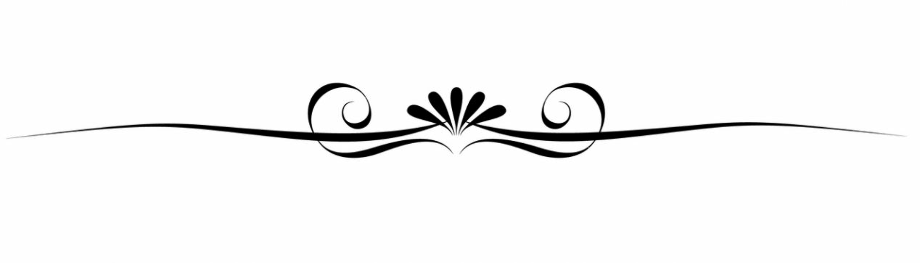

Nestled deep within the Spiti valley in east Himachal Pradesh bordering Tibet, is located the monastery of Tabo in one of the remotest mountainous regions of India. Before the political boundaries of the nation were drawn, Tabo was a part of the kingdom of Western Tibet. With its high-altitude plateau with an average elevation of 4000 metres, a pervading Buddhist culture with about 20 monasteries, physically and culturally Spiti seems to have more in common with Lhasa, the Tibetan capital rather than New Delhi.

Spiti was opened to tourism only in the year 1993. Even now it is out of bounds between November and May from the Manali-Rohtang-Kunzum route. The passes are closed during those months, and can be accessed only through the Shimla-Kinnaur route. But even in this route, the roads are frequently closed due to heavy snowfall. And there is every possibility of getting snow trapped for days or even weeks.

Ajanta of the Himalayas

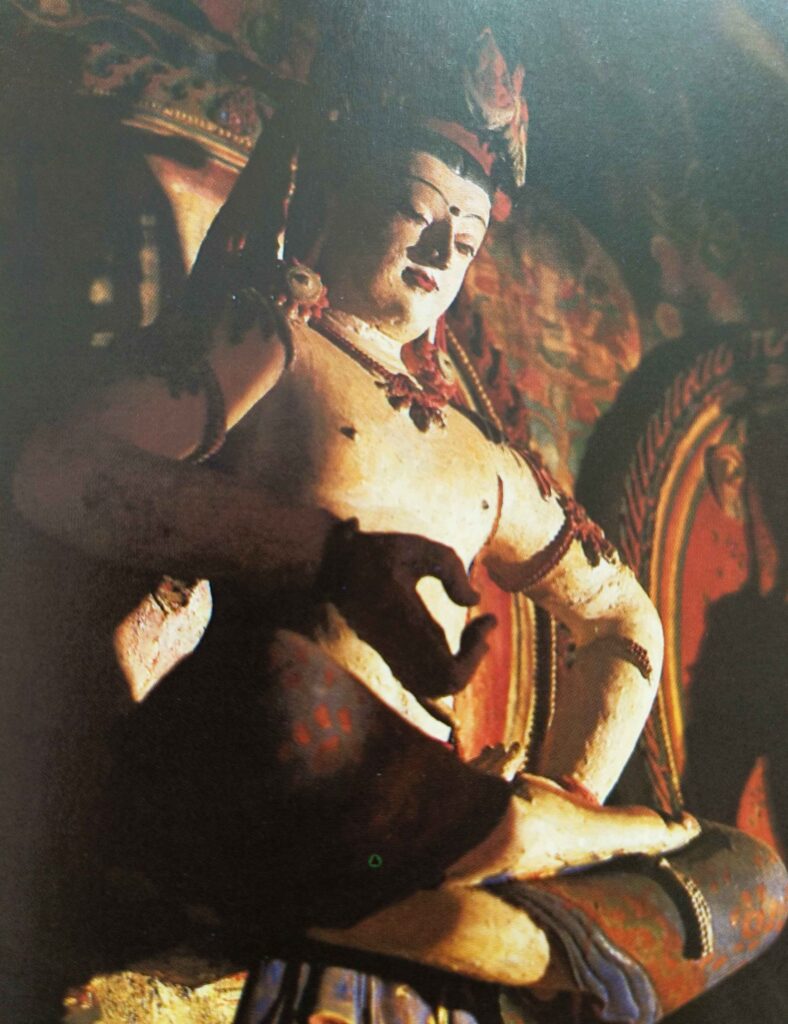

Established in 996 AD, Tabo is the oldest continuously operating Buddhist monastery in India. It predates other famous sites like Tawang (Arunachal Pradesh), Rumtek (Sikkim), Thiksey and Hemis (in Ladakh). It acted as a historical, cultural and spiritual intermediary between India and Tibet. The extraordinary beauty of its frescoes and sculptures has earned for it the title – “Ajanta of the Himalayas.”

Its remote location — accessible after a gruelling 2-day drive over mountainous roads from Shimla — kept it safe from the onslaught of the Islamic invaders. That is why it remained totally unscathed in comparison to other Buddhist nerve centres such as Nalanda and Vikramshila. Being geographically located in the rain-shadow area, its landscape resembles the cold deserts of Ladakh and Tibet. Such is the geo-physical nature of the area.

Tabo was founded by Rinchen Zangpo who was a student of the famous Indian master Atisha Dipankar. It was an important seat of Buddhism where Tibetan and Indian monks studied together. They translated many Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit into Tibetan. Hence, we find a fusion of Indian and Tibetan themes in vividly preserved magnificent paintings and sculptures that adorn the original temple and the monastery.

Tabo was the first monument in India to use the Tibetan language as a medium of communication. In view of Tabo’s important contribution towards the art and philosophy of Buddhism, it was also called a lamp for the kingdom (of Western Tibet). In Tabo, we are witness to a 1000-year-old unbroken tradition.

A Treasure Trove

I visited Tabo several years back and was absolutely awestruck by what I saw. I had not expected to find such a treasure trove of paintings and sculptures in the middle of a barren, high-altitude cold desert. What follows is an eye witness account and my research based on two extraordinary books. (See the bibliography at the end of the essay). Unfortunately, photography is not allowed inside the monastery complex. Hence, all the photographs that follow have been sourced from these two books.

People in this area practice Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism. Having its foundation in Mahayana school of Buddhism, and departing from the early, atheistic Hinayana Buddhism, this path accepts that intense devotion to a perfected being aids one’s spiritual development. As a result, many Tantric elements were borrowed from Hinduism, such as Ishta Devata Puja, use of Mantra, Yantra, Mandalas, Mudras and several other Yogic practices. The Bhakti element is also very strong in Vajrayana. Thus, Vajrayana can be seen as a fusion of Buddhism and Tantra.

The strongest note of Mahayana Buddhism, its stress on universal compassion and fellow-feeling, was an ethical application of the spiritual unity which is the essential idea of Vedanta.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 208

The Tabo monastery complex contains several chapels and stupas apart from the main temple.

The Main Temple

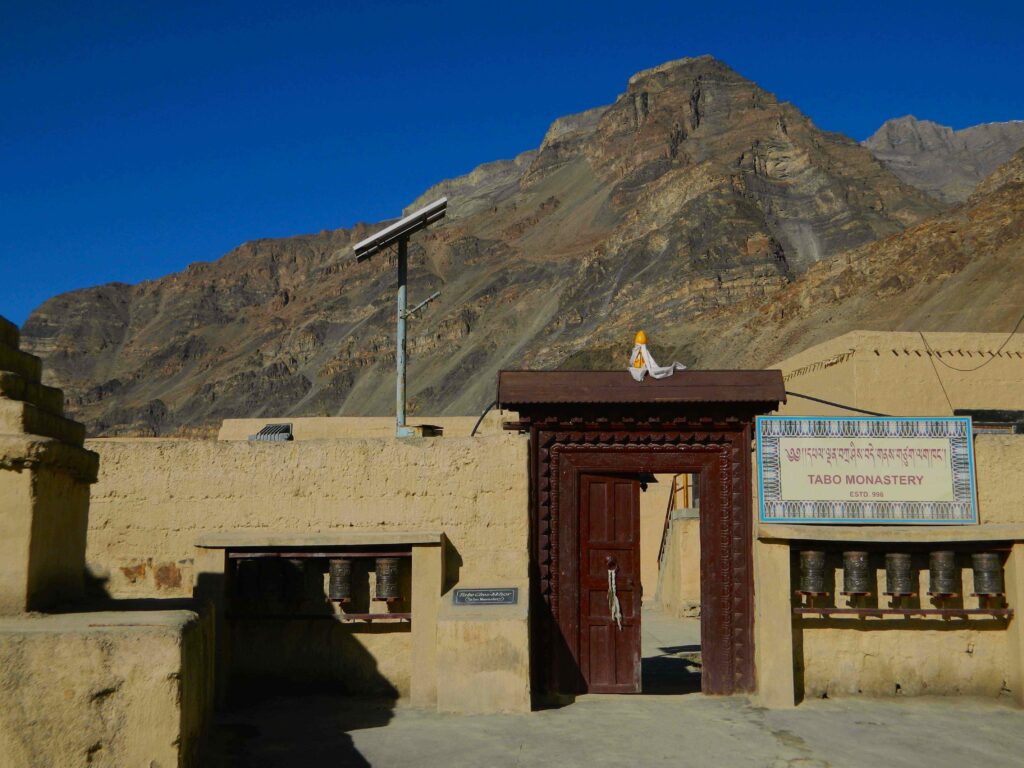

In this write-up I focus on the main temple which contains multiple artistic themes. But before we enter the assembly hall in the main temple, we have to cross the entrance hall where we encounter fierce looking Guardian deities – Mahakala and Hayagriva – who protect the Dharma and ward off negative influences. This is similar to the dwarpals in Hindu temples.

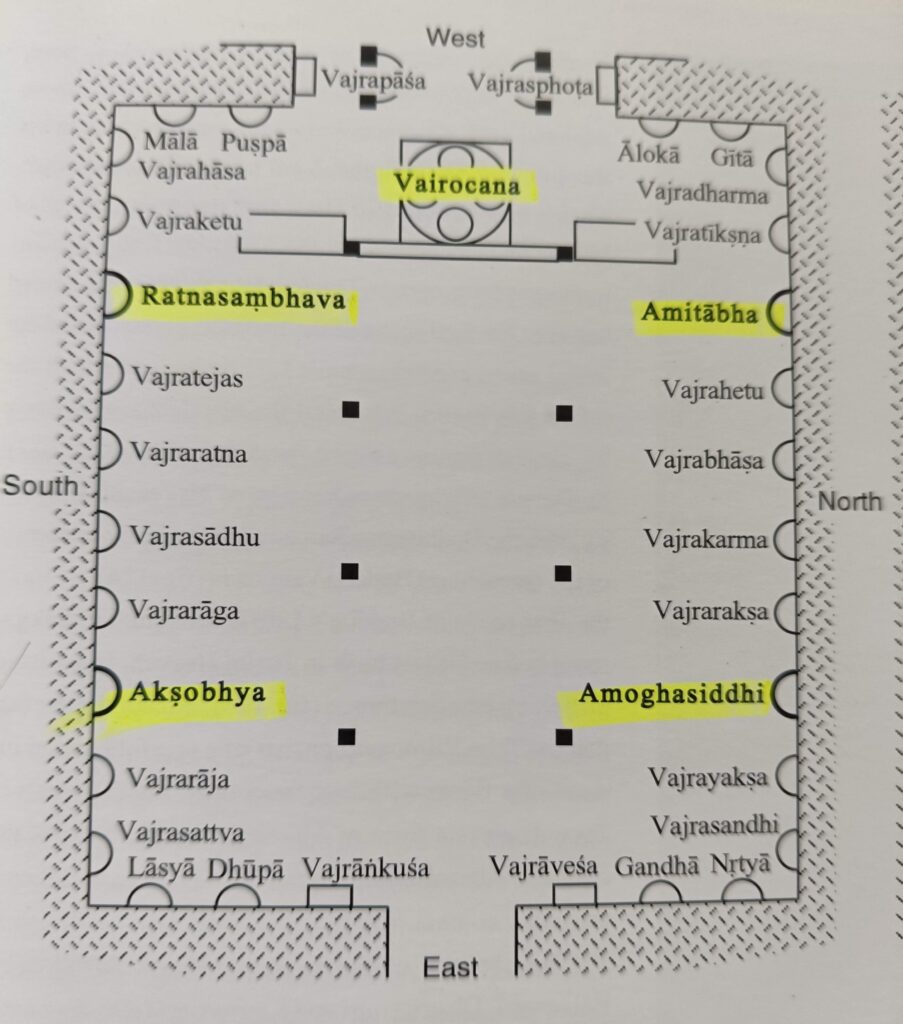

The main temple of Tabo is one of the masterpieces of Indian and Tibetan art. The assembly hall is conceived of as a Vajra-dhatu Mandala. Vajra or thunderbolt signifies indestructibility and spiritual power, dhatu is element or realm, and mandala represents the sacred geometric space.

Mandala is a symbol of unity and unification. Usually a centre is defined by four cardinal points. In a Mandala ritual, the seeker visualizes a certain deity and merges with it in his consciousness, becomes unified with it and becomes the deity himself. The philosophy is same as the upasana of the Ishta Devata in Hindu Tantra.

Dhyani Buddhas

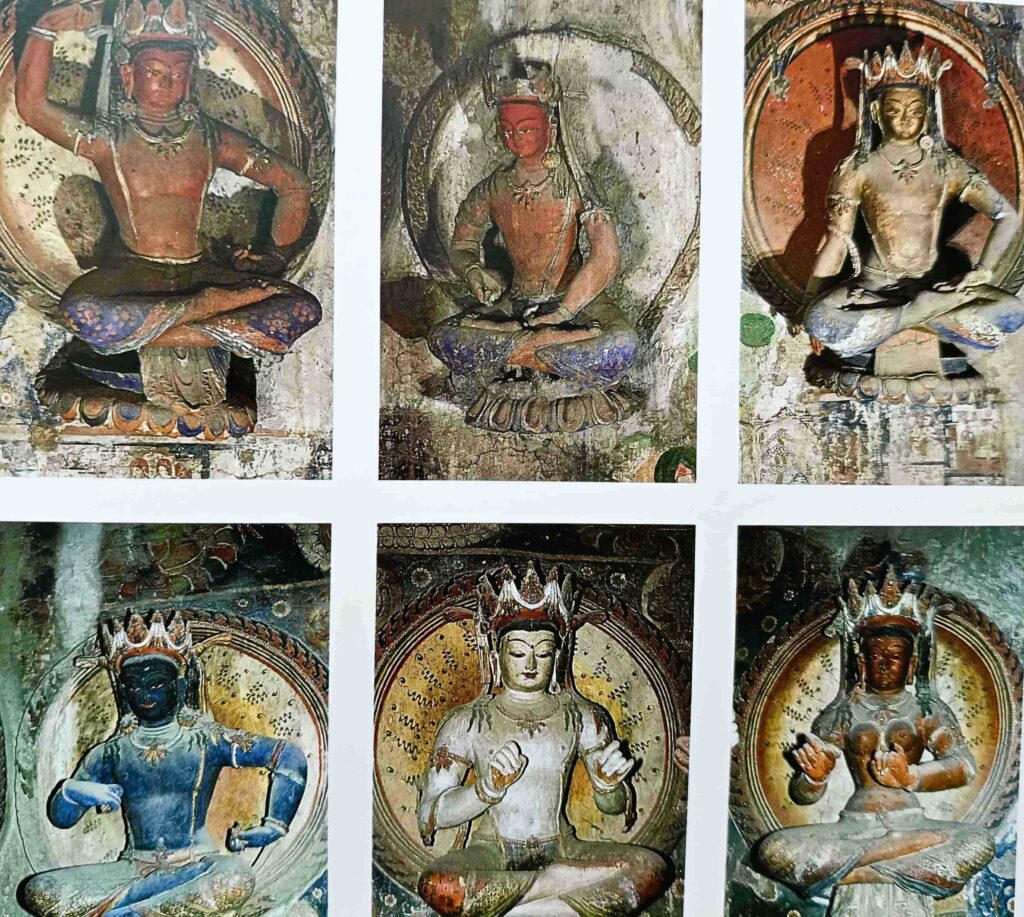

In order to properly understand what the Vajra-dhatu Mandala in the assembly hall contains, we have to know the concept of the five Dhyani Buddhas in Tibetan Buddhism or Vajrayana. According to Vajrayana, the five Dhyani Buddhas (also known as the Wisdom Tathagatas) represent different aspects of enlightenment and are used as aids to meditation. Their names and what they represent are:

| Vairochana | Dharmakaya (Truth body) and all-encompassing wisdom |

| Akshobhya | Wisdom of the mirror-like mind |

| Ratnasambhava | Wisdom of equality and generosity |

| Amitabha | Wisdom of discriminating awareness |

| Amoghasiddhi | Wisdom of accomplishing action |

Meditation on these five Buddhas leads to purification and transformation of the five Skandhas (or aggregates) like forms, sensations (feelings), perceptions, mental constructions and consciousness. So the Vajra-dhatu Mandala is a sacred space where we are in the midst of these powerful, purifying influences that help us deal with the impurities of the five aggregates that make up our being. In fact, the most famous representation of the Vajra-dhatu Mandala is the world-renowned magnificent structure of the Borobudur in Java/Indonesia.

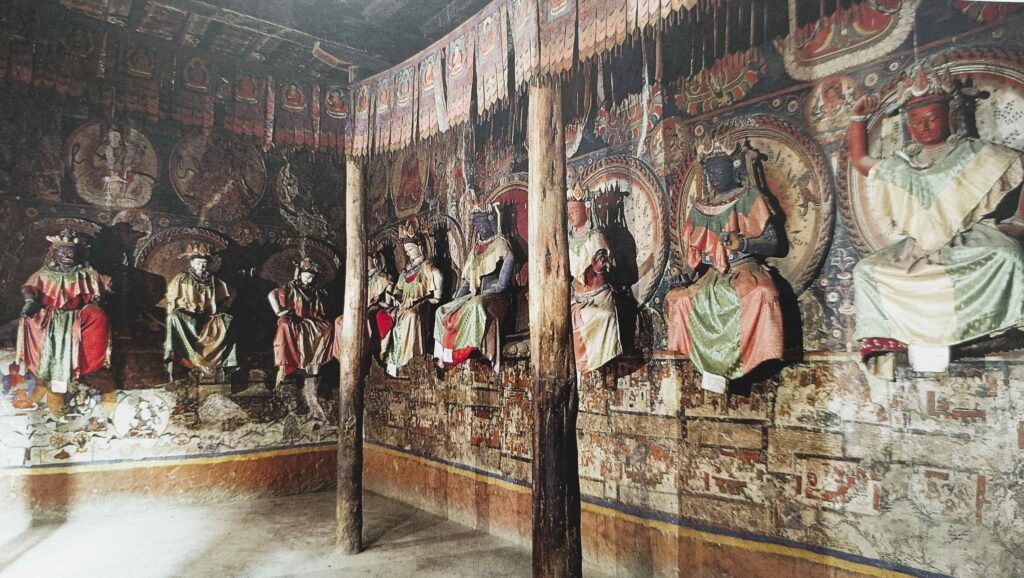

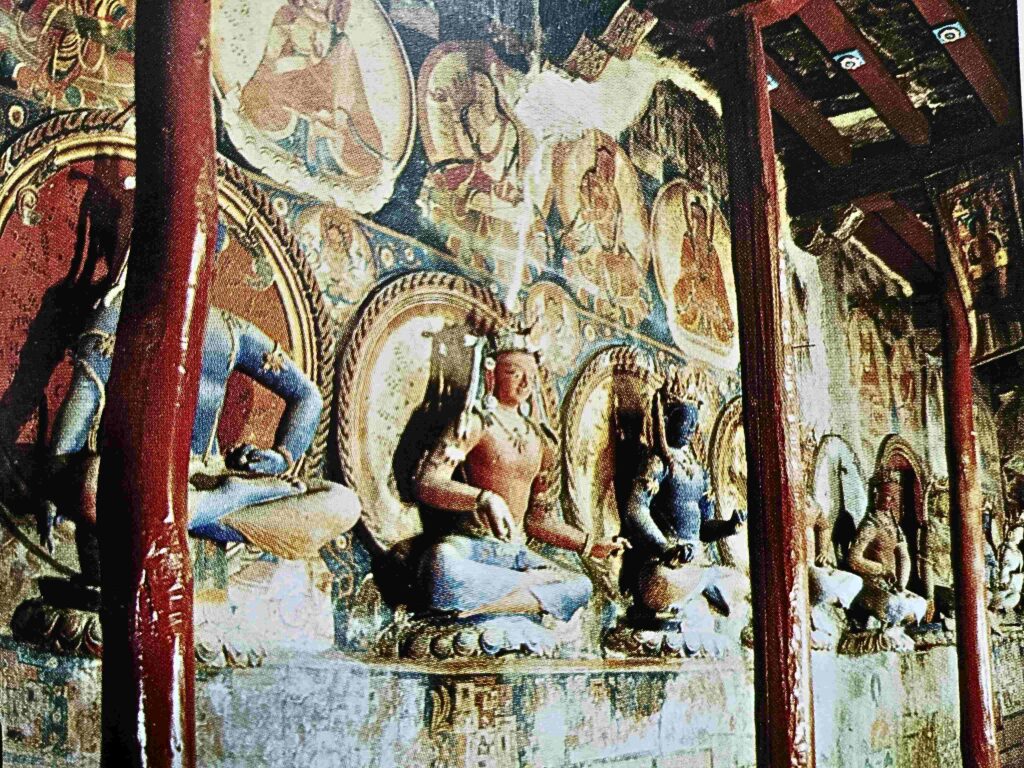

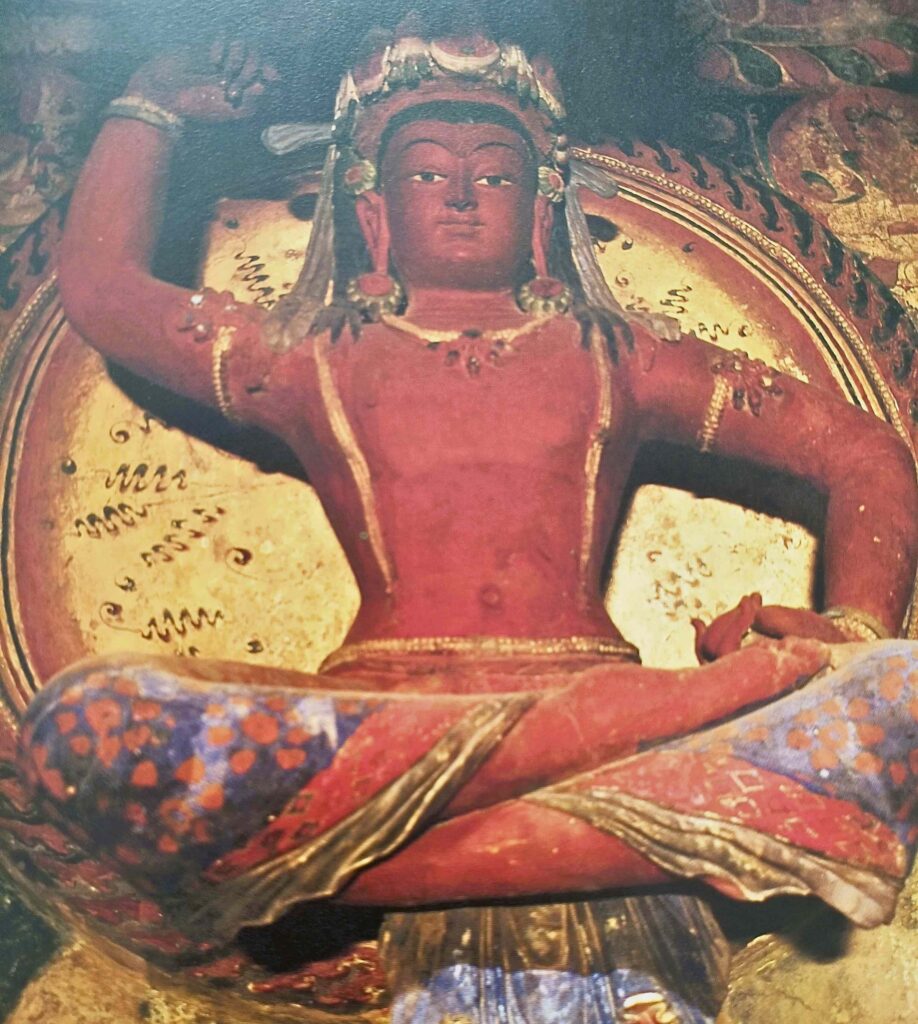

The central figure in the Vajra-dhatu Mandala is a four faced Vairochana situated towards the western wall of the assembly hall behind an altar. In the southern and northern walls are placed the other four Dhyani Buddhas – two on each wall.

Other Deities

Apart from the five Dhyani Buddhas, the four walls contain other enlightened beings (Bodhisattvas) such as Vajrapani, Maitreya, Avalokiteswara etc. and female goddesses (Shaktis) such as Tara, Lochana, Vajra Dakini etc.

The Vajra-dhatu Mandala also contains fierce looking deities because the Vajrayana approach includes confrontation with the negative aspects of our consciousness – what we may call, the Asuric forces. In order to confront and defeat the Asuric forces, fierce looking deities with immense power are invoked. You can say they are the Tibetan versions of Narsimha!

All these figures put together take the total number of deities in the Vajra-dhatu Mandala to thirty-three. Imagine being in a meditation room surrounded by 33 powerful wisdom emanations — the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, female goddesses, Dakinis and fierce deities!

Murals and Frescoes

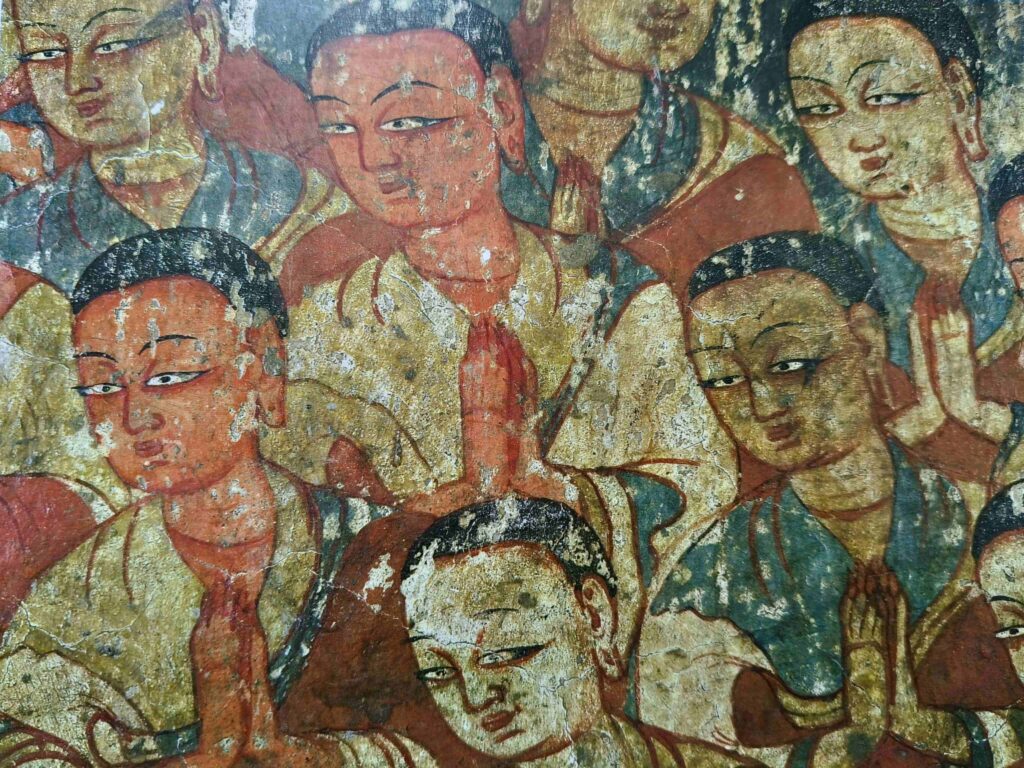

To complement the unique clay sculptures of the Vajra-dhatu Mandala, we also find beautiful and fascinating murals and paintings with striking resemblance to the Ajanta paintings. These paintings were done on mud plastered walls with natural pigments and are one of the oldest and well persevered murals in India.

The frescoes on the walls of the main temple have two main themes. One is the life and seeking of Sudhana, a prince whose life was similar to that of Buddha and the other relates to the different incidents from the life of Gautam Buddha.

The Tabo monastery as a whole and the Vajra-dhatu Mandala in particular is simply unique and marvellous. Symbolically, it is home to everything one can experience in the meditative process.

Tabo has been rightly called “a lamp for the kingdom” because it represented a centre for the light of knowledge and enlightenment. It was not just a monastery but a centre for translation, education, art, ritual and philosophy. Monks from both Tibet and India went there to learn, teach and translate scriptures from Sanskrit to Tibetan. It is due to places like Tabo that Buddhist philosophical scriptures, which were taken there from Nalanda and Vikramshila, survived for posterity when those famed Buddhist universities fell to the fire and sword of the Islamic marauders. To this day, several hundred manuscripts of birch leaf and hand-made paper are well preserved in the archives of the monastery.

Bibliography:

- Pics 3, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 sourced from Tabo: A Lamp for the Kingdom — Early Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Art in the Western Himalayas by Deborah E Klimberg Salter

- Pics 1, 5, 7, 10, 13, 15, 21, 22 sourced from The Forgotten Gods of Tibet, Early Buddhist Art in the Western Himalayas by Peter Van Ham & Aglaja Stirn

Further Reading: Sacred Spaces

~ Design: Beloo Mehra