Volume VI, Issue 1

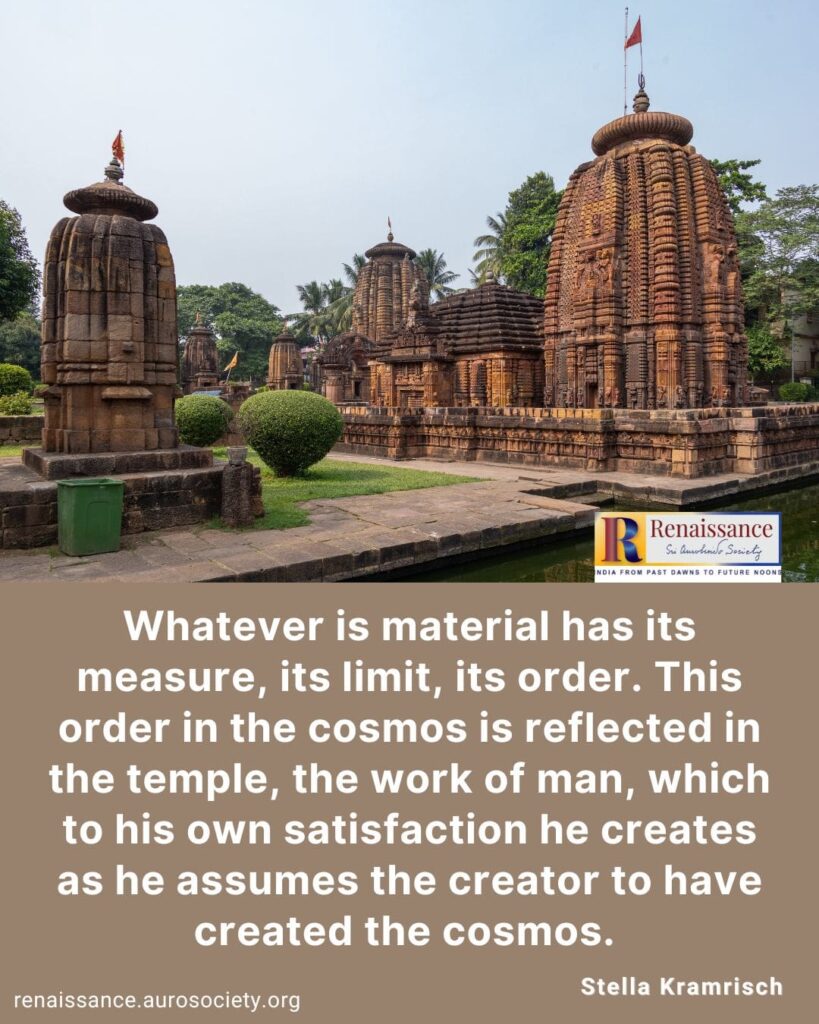

Author: Stella Kramrisch

Editor’s Note: We feature excerpts from a talk delivered in 1967 by the noted art historian and scholar, Stella Kramrisch. This and other papers presented at the seminar held in Varanasi were edited and compiled by Prof. Pramod Chandra of University of Chicago and published under the title Studies in Indian Temple Architecture in 1975. The book is available in public domain at archives.org.

The Śilparatna says that the temple, prāsāda, should be worshipped as Puruṣa. In her talk, Kramrisch explains what is this Puruṣa as which the temple should be worshipped. She also describes how the temple as a work of architecture represents the body of this Puruṣa. Featured below are those excerpts which highlight the deeper symbolic aspects and emphasize the sacredness of the entire architectural plan of the temple. We have left aside the more technical details of temple architecture.

We have also made some minor formatting revisions and have added sub-headings to facilitate online reading.

Every form of art, every great tradition, rests on certain assumptions; if we do not wish to call them intuitive insights, or religious inspirations, or revelations, we simply call them assumptions. And this fundamental assumption of the Puruṣa shaped Indian thought and creative form from the Ṛgveda onwards. Here we are primarily interested in form, in architecture as form, as a creative process which by its own tangible, visual, means creates the equivalent of that pervading notion, the Puruṣa.

What or who is the Puruṣa?

Ṛgveda10.90 says He is the entire world. From Him was born Virāj, and from Virāj, Puruṣa. This reciprocal relation of autogenesis requires some comment.

Who is Puruṣa? Puruṣa is Man. But Man is here a term of reference, the nearest at hand, if we experience, feel and think allusively in referring to something which is beyond form. For is it not the message of created Form to convey that which is beyond all forms?

Puruṣa, which is beyond form, is the impulse towards manifestation. This impulse towards manifestation is experienced within creative man in the image of Man as Supernal Man, Primordial Man, or the image of ‘‘Man as the creative impulse”. This creative impulse, however, as soon as felt and conceived, is immediately productive or procreative. From Him was born Virāj.

Virāj is cosmic intelligence ordering the process of manifestation; and from that cosmic ordering intelligence once more that very impulse in a self-generating way is born. The relation in its timeless, extreme logic is projected from Man, the experiencing microcosm, into his experienced macrocosm.

This is the only priority between these two, man and the cosmos. In each the relation of Puruṣa and Virāj is the same. They are there, the one presupposes the other the moment creation begins. They are the impulse and its ordering intellect, the latter as it were, latent as well as imperious within the former.

Temple as Puruṣa Conceived by Means of Prakṛti

The Agni Purāṇa, a much earlier text than the Śilparatna, says that the impact, Śakti, and Form, Ākṛti, of the temple is Prakṛti. Prakṛti is Primordial Matter, that is Matter before it became matter, the principle of matter. The principle of matter, its impact, Śakti, realized as Form, is coordinated with Virāj, the ordering Intellect.

Matter itself is measured out. Whatever is material has its measure, its limit, its order. This order in the cosmos is reflected in the temple, the work of man, which to his own satisfaction he creates as he assumes the creator to have created the cosmos. The temple is Puruṣa conceived by means of Prakṛti.

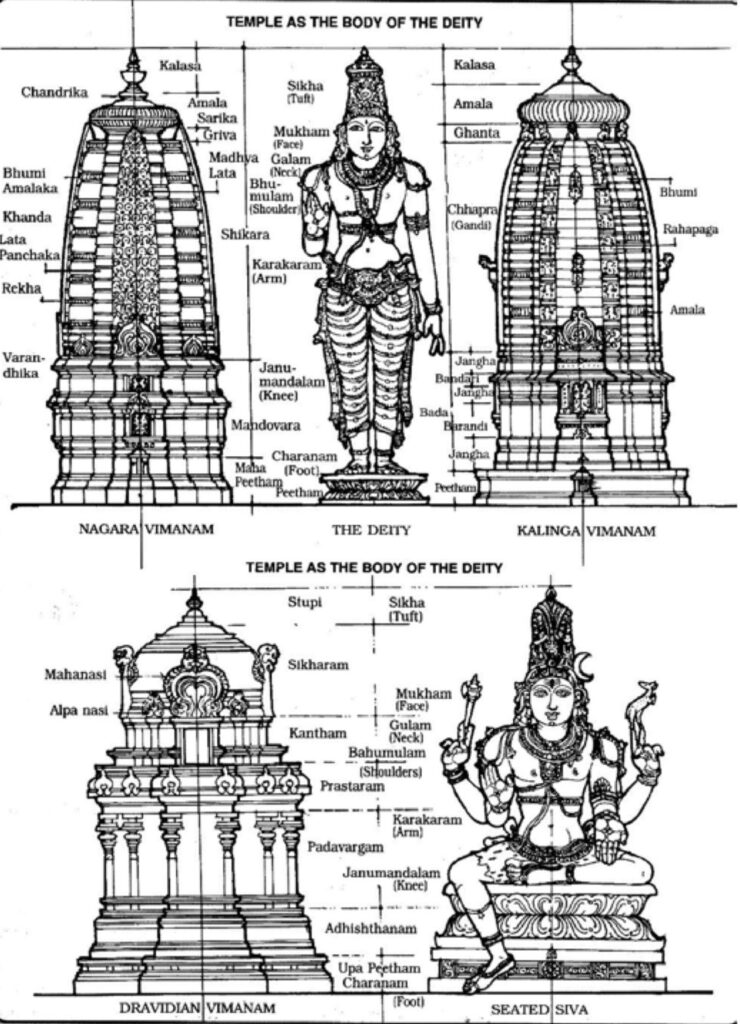

The Agni Purāṇa, practically in the same breath, says that the door of the temple is its mouth; the skandha, the platform terminating the trunk of the superstructure, represents the shoulders of the Puruṣa; the bhadra, or projection, the arms. And thus down to the wall, the jaṅghā, or “leg,” and to the very bottom, to the lowermost molding (pādukā), the feet.

The names of these and other single parts of the body of man are transferred to essential parts of the structural organism of the temple in its own right. Neither their situation nor their proportions in the body of the temple are meant to be compatible with or referred back to the human body.

Pratimā, the Jīva of the Temple

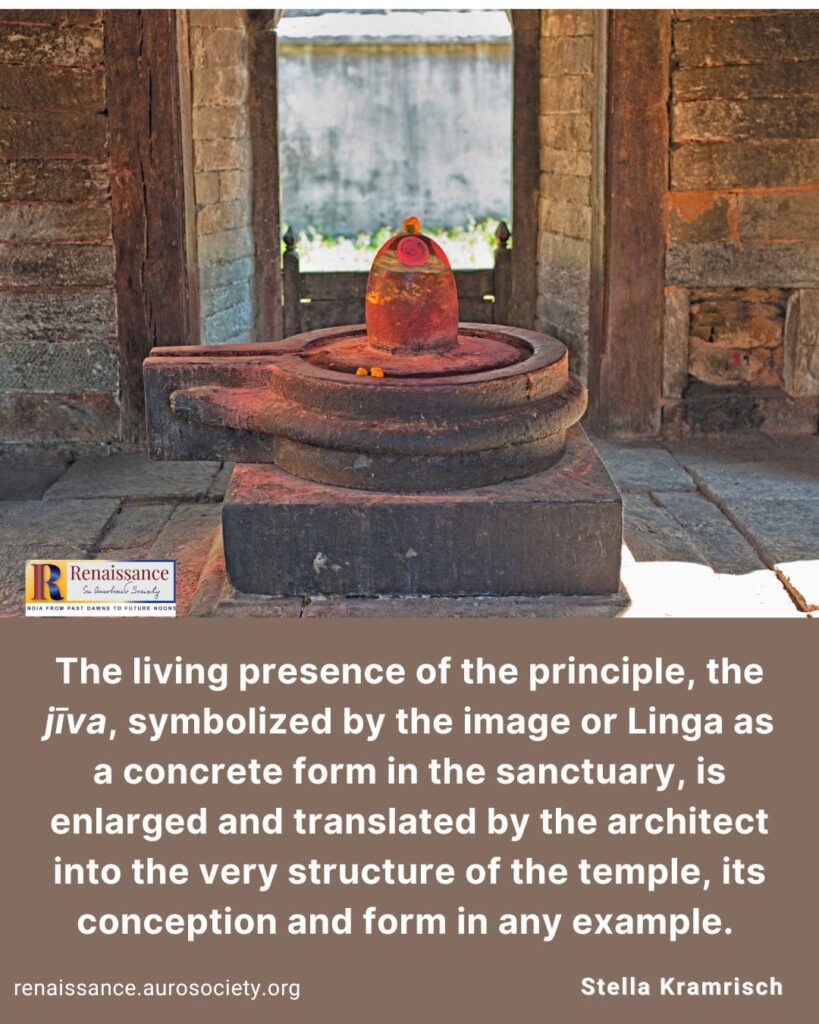

The Agni Purāṇa further says that the image in the temple, the pratimā, is the very jīva, the very life, of the temple. Such references are in the nature of images. They are not meant to be taken literally. They act as points of reference so that we may feel and see the living presence of that entity called Puruṣa.

Other texts, earlier and later ones such as the Viṣṇusaṃhitā, and also the Śilparatna, speak about the Vairāja form of the prāsāda. They emphasize the Puruṣa as Virāj, the order, the measure, the intellectual function within the creative act of architecture. Here, too, the brief references to the mouth, the head, or mastaka, the jaṅghā, or leg, that is, the vertical wall in its middle portion, are just external marks indicating the living presence of the Puruṣa.

The living presence of the principle, the jīva, symbolized by the image or Linga as a concrete form in the sanctuary, is enlarged and translated by the architect into the very structure of the temple, its conception and form in any example. It is seen in even the latest ones, and even in those of no considerable artistic consequence. And is true not [only] of Hindu denomination, we see this in the Jaina temples also, for example the one at Chittor.

READ

The Vedic Spirit and Temple Design

Presence of the Puruṣa Manifesting on the Temple Exterior

Even there the very principle of the Puruṣa in thus organizing the manifesting impulse is built up in visual terms. The monument is indwelt by the presence of the Puruṣa which is manifest on the outside of the temple. Its effect relies on mass only, and mass which is piled up so that it coheres visually, dynamically, while one shape rests on the other without physical stress, without actual tension, yet on all levels it progresses in all directions while visually its thrust is upwards.

In the most elaborate temples of the Nāgara style, the dynamic movement is at the same time organized in the opposite direction towards the center of the building, the innermost sanctuary, in re-entrant angles.

In principle, the prāsāda as Puruṣa is meant to be seen from the outside. Because in the interior there is but the garbhagṛha, the womb-chamber. It is a stark, simple cubical space without the rich articulation of the exterior. Its mystery lies in the realm of the female within Man. For it is the place of gestation, generation and transformation, the place of the embryo and of a new birth where Deity is made manifest by image or symbol.

Sāndhāra prāsādas, where the garbhagṛha is ensconced in a double set of walls allowing for an inner ambulatory, only seemingly belie the polarity between the pristine secret of the garbhagṛha in its simplicity and the intricate organization of the exterior, in this case a double exterior of the walls of the prāsāda.

Prāsāda as Puruṣa Given Form in Terms of Architecture

The texts on the prāsāda as Puruṣa do not go beyond the assigning of the names of the parts of the body of man to architecturally significant parts of the structure. And this structure, in its entirety is set up to be seen from the outside only. The high superstructure has no interior to offer for this is not meant to be seen. It is closed off from the garbhagṛha, as a rule, by a flat ceiling.

However, the total conception of the prāsāda as Puruṣa is given form by the architect in terms of architecture. The order and coherence of the architectural themes and motives form as closely knit an integument as is the skin of the body of man.

The logic or pattern of the architectural themes and motives is enforced by more than one factor. Origins of a structural or technical nature are linked by sets of rules. These rules are subservient to a sense of proportion and rhythms. And they vary according to place and time.

[…]

The prāsāda as Puruṣa is permeated by Sakti and pervaded by Virāj, the ordering intellect, as it shows forth stepping out in the four directions from the center in the garbhagṛha. Its impact is visible in the buttresses, their centrifugal gradations and centripetal recesses.

Each of their planes in turn is informed by an architectural vitality. This shows forth from the pattern of the three-dimensional texture of the walls, the body of the Puruṣa.

Read full article.

~ Design: Beloo Mehra