Volume VI, Issue 3

Compiled by Beloo Mehra

Editor’s note: The following selections are excerpted from the book ‘Paintings and Drawings by the Mother’ (e-version available HERE). We have made only a few formatting revisions for ease of online readability.

Introduction

The Mother did not give her personal career as an artist a primary importance. Hence it is not commonly known that she was an accomplished artist… In spite of her limited artistic activity in later years, she never lost the power of her observing eye nor the sureness of her hand. Nor did she allow her consciousness of beauty and her aesthetic vision to become diminished in the midst of her intensive spiritual endeavours and manifold responsibilities as the head of Sri Aurobindo Ashram.

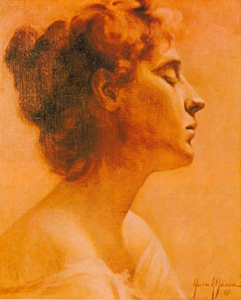

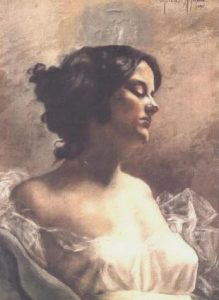

The Mother, born Mirra Alfassa (1878-1973) loved to draw and paint from her childhood. Though art was only one of her many interests, it occupied a prominent place in her early life. She began to take drawing lessons at the age of eight. Two years later she started to learn oil painting and other painting techniques. By the time she was twelve she was doing portraits. In 1892, when she was fourteen, one of her charcoal drawings was exhibited at the International “Blanc et Noir” Exhibition in Paris.

Inner Dimension of the Mother’s Early Artistic Development

A glimpse of the inner side of the Mother’s early artistic development is of greater interest than any outward facts. We know from several statements in her talks that her conscious practice of meditation had begun spontaneously at the age of five. A great “light” which she often felt above her head and later penetrating her brain had begun to shape her life, though she could not yet understand what it was. Concentrated work on the purely mental faculties would come at a later stage.

From about the time she started drawing and painting, the focus was on perfecting the “vital being” whose domain is

sensations, emotions, life-energies.

All aspects of art and beauty, but particularly music and painting, fascinated me. I went through a very intense vital development during that period, with, just as in my early years, the presence of a kind of inner Guide; … all centred on studies: the study of sensations, observations, the study of technique, comparative studies, even a whole spectrum of observations dealing with taste, smell and hearing—a kind of classification of experiences.

And this extended to all facets of life, all the experiences life can bring, all of them—miseries, joys, difficulties, sufferings, everything—oh, a whole field of studies! And always this Presence within, judging, deciding, classifying, organising and systematising everything.

~ The Mother, Agenda, Vol. 3, pp. 280-281

An Artist’s Vision

At a young age, the Mother not only acquired the techniques of drawing and painting but learned to see with the eyes of an artist. She once described what this means, in its most basic terms:

There is a considerable difference between the vision of ordinary people and the-vision of artists. Their way of seeing things is much more complete and conscious than that of ordinary people. When one has not trained one’s vision, one sees vaguely, imprecisely, and has impressions rather than an exact vision.

An artist, when he sees something and has learned to use his eyes, sees—for instance, when he sees a face, instead of seeing just a form, like that, you know, a form, the general effect of a form, . . . he sees the exact structure of the face, the proportions of the different parts, whether the face is harmonious or not, and why; . . . all sorts of things at one glance, you understand, in a single vision, as one sees the relations between different forms.

~ The Mother, CWM, Vol. 6, p. 83

Also read the Mother’s words on:

Art as a Discipline for Developing the Consciousness

An experience the Mother had when she was fourteen, though it relates more to music than to the visual faculties, shows how readily her keen aesthetic response to beauty could intensify into a sudden spiritual opening, even at this age:

The Jewish temples in Paris have such beautiful music; oh, what beautiful music! I had one of my first experiences in a temple. It was at a marriage, and the music was wonderful—Saint-Saens, I later learned; organ music, the second best organ in Paris—wonderful!

I was 14 years old, sitting high up in the galleries with my mother, and this music was being played. There were some leaded-glass windows—white, with no designs. I was gazing at one of these windows, feeling uplifted by the music, when suddenly through the window came a flash like a bolt of lightning. Just like lightning. It entered—my eyes were open—it entered like this (Mother strikes her breast violently), and then I… I had the feeling of becoming vast and all-powerful…. And it lasted for days.

~ The Mother, Agenda, Vol. 2, pp. 195-196

Years in the Studio

Having completed her regular schooling at the age of fifteen, she joined an art studio in Paris to study painting. In all likelihood it belonged to the Academic Julian, an organisation with several studios founded by Rodolphe Julian in the latter part of the nineteenth century. In those days women were not admitted to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. […]

The Mother continued to work in this studio until 1897, when she married the artist Henri Morisset. During the next few years, she participated in the stimulating artistic life of turn-of-the-century Paris and associated with some of the leading artists of the period. […]

It was undoubtedly during her years of concentrated work in the studio that the Mother matured from a gifted child into an accomplished artist. But she had no ambition for fame or a successful career. Nor was art itself her single all-absorbing preoccupation. She always spoke of it as one part of the many-sided growth in consciousness which was taking place in these years. The spirit in which she studied may be inferred from what she said later about Art and Yoga:

The discipline of Art has at its centre the same principle as the discipline of Yoga. In both the aim is to become more and more conscious; in both you have to learn to see and feel something that is beyond the ordinary vision and feeling, to go within and bring out from there deeper things.

Painters have to follow a discipline for the growth of the consciousness of their eyes, which in itself is almost a Yoga. If they are true artists and try to see beyond and use their art for the expression of the inner world, they grow in consciousness by this concentration, which is not other than the consciousness given by Yoga.

~ The Mother, CWM, Vol. 3, p. 105

Her Paintings in Paris and Japan

Only about forty of the Mother’s paintings are available to us today. More than half of these belong to her early years in France (before 1914, when she made her first trip to India), including her visits to Algeria (1906 and 1907). Other early works, which she considered to be among her best, were either sold or presented to friends and are now lost to us.

She did a fair amount of painting, both in Paris, where she and Morisset had their flat with a studio in the garden, and on trips to the countryside. Six of her works were exhibited in the prestigious Salon de la Societe Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1903, 1904 and 1905. These works are listed by name in the catalogues of the Salon; one of them was reproduced in the illustrated catalogue of the 1905 exhibition.

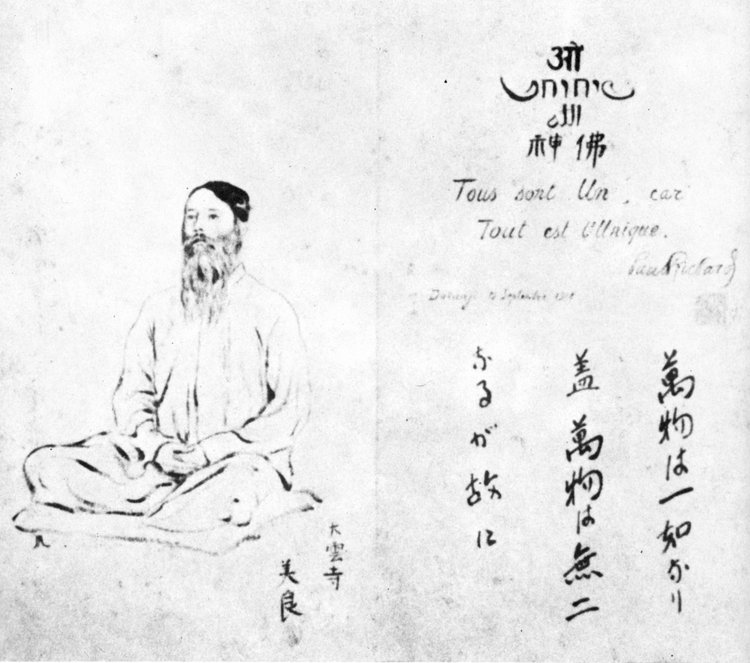

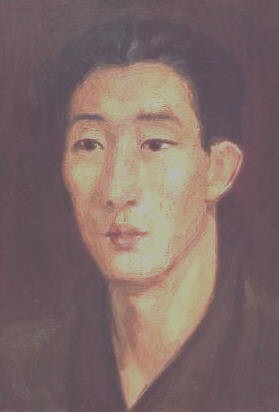

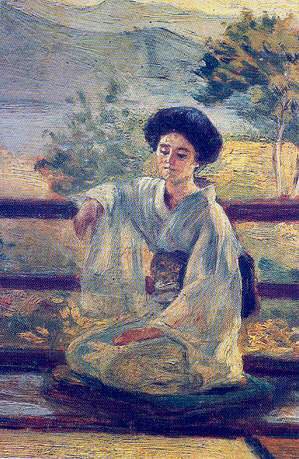

The Mother also did a number of paintings and drawings while she was in Japan, between 1916 and 1920. There she acquired the Japanese technique of water-colour painting, working directly with brush and black India ink. When she returned to India in 1920, she brought with her seven paintings and some drawings which she had done in Japan.

Oil on board, 1916-20, Japan

Oil on canvas, 1918, Japan

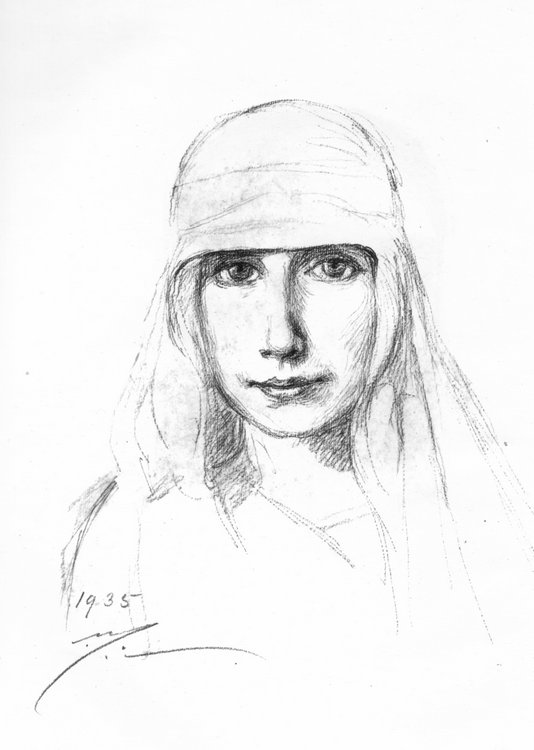

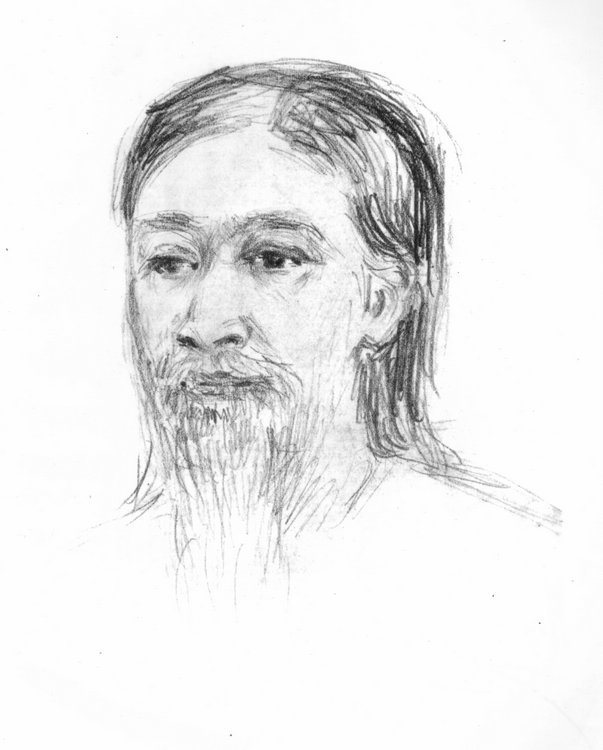

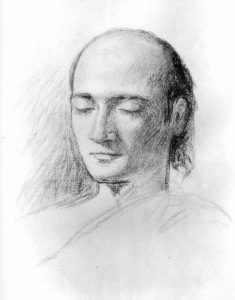

Portraits in Pondicherry

In Pondicherry, the Mother rarely had time to undertake oil paintings. Her spiritual work and practical responsibilities became all absorbing. And she preferred to bring out latent artistic faculties in others rather than display her own abilities.

But she did quite a few drawings of the highest quality and artistic value. These are mainly portraits. Those who saw her doing these portraits describe how within minutes, with a few rapid strokes, a living face would be completed.

The Mother herself did not attach much importance to what she had produced as an artist. No doubt, she could have done much more if she had chosen to apply her talent, training and spiritual vision to serious painting in her mature years. Her early works, for all the skill and beauty we may admire in them, are in a style which may be said to belong to the past. The Mother was well aware of this.

She spoke of the future of art in her talks. Yet she did not herself attempt to realise its highest possibilities as she saw them. She left this for others to attempt. When she was urged to take up painting again, she replied that she had no time for it. Her later drawings were generally a spontaneous expression on the spur of the moment, not a premeditated artistic creation.