Volume V, Issue 10

Author: Beloo Mehra

Editor’s Note: This two-part article focuses on the sacred origins of dance and drama as per the Indian cultural tradition. In part 1, we read about the legend concerning the beginnings of dance as a sacred art. Also emphasized here is an integral vision of art in India.

“In the night of Brahma, Nature is inert. And cannot dance till Shiva wills it; He rises from His rapture and dancing sends through matter pulsing waves of awakening sound, and lo! Matter also dances appearing as a glory round about Him.”

(Ananda Coomaraswamy, The Dance of Shiva)

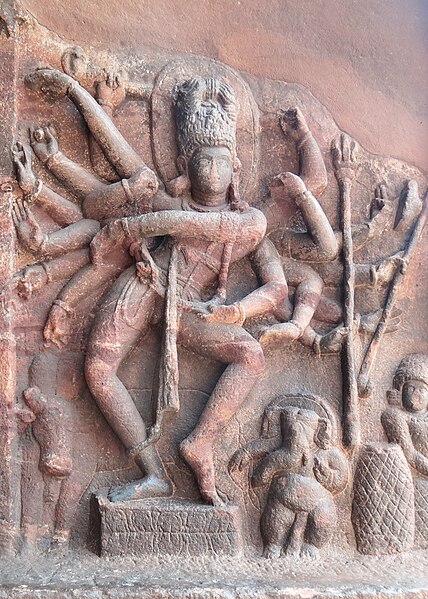

This is how the Indian tradition speaks of the beginning of creation. It is the waking up of the inconscient Matter to the dancing of Shiva, the Lord of Dance, Nataraja.

The Dance Begins

The Nataraja expresses “the rapture of the cosmic dance with the profundities behind of the unmoved eternal and infinite bliss,” says Sri Aurobindo. It is said that the art of dance was born with the dance of Shiva and Parvati. The story goes like this.

While composing the Nātyashastra, Bharata felt that for a complete aesthetic experience, the drama, needed something more than mere dialogue and the rigid body movements. Lord Brahma suggested that he approach Lord Shiva. Shiva was more than happy to lend his expertise. He called upon Tandu to expound and demonstrate the dance, Tāndava.

But something was still missing. Tāndava was a male movement and it still did not bring in the grace and beauty of the female form. It was Devi Parvati who then gave to Dance, the Lāsya, or the feminine style, making it whole. The tāndava without the lāsya is as incomplete as Shiva without Parvati. One without the other is likely to tilt the balance of the whole world.

***

“Stability and movement, we must remember, are only our psychological representations of the Absolute, even as are oneness and multitude. The Absolute is beyond stability and movement as it is beyond unity and multiplicity. But it takes its eternal poise in the one and the stable and whirls round itself infinitely, inconceivably, securely in the moving and multitudinous.

“World-existence is the ecstatic dance of Shiva which multiplies the body of the God numberlessly to the view: it leaves that white existence precisely where and what it was, ever is and ever will be; its sole absolute object is the joy of the dancing.”

(Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 21, p. 85)

But dance for the Indian mind is not only limited to Shiva.

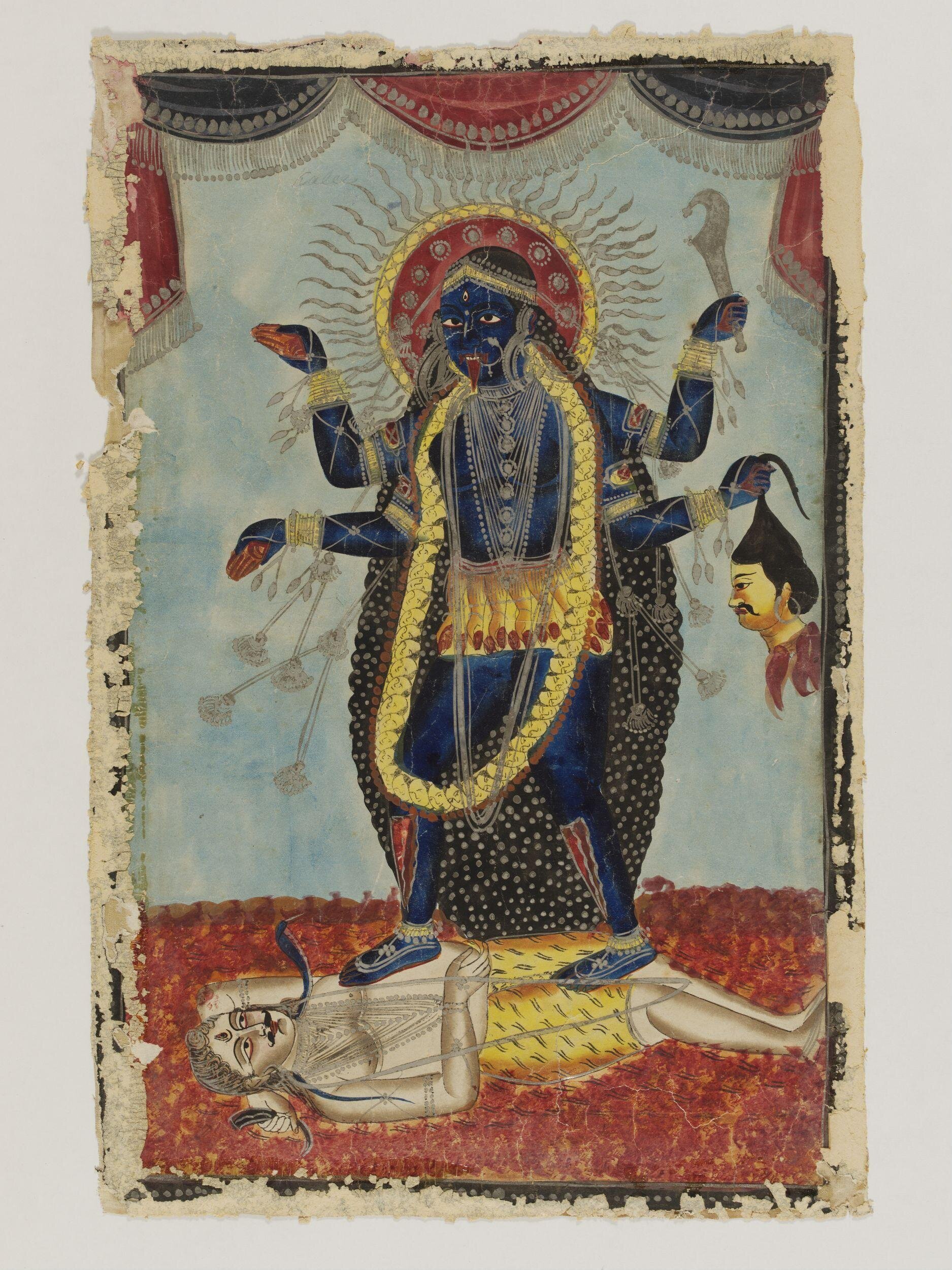

We also have Mother Kali dancing over the body of Shiva. Shiva, in the Shaivite tradition, is the all-pervading eternal primeval consciousness of the universe and beyond. The dance of Kali (the Time) upon the ultimate, unchanging Timeless reality of Shiva causes the constant cycles of creation and destruction of all things in the universe.

And then there is the delightful dance of Krishna, the Rāslila. Dancing with Radha and the Gopis and Gopas in the moonlit groves of Brindavan, Krishna is Anandmaya. This is His dance of Divine Delight with the souls of men and women liberated in the world of Bliss. This bliss is secret within us, and we discover it when we dance on the Divine’s tune.

Indian tradition speaks of Nritta as pure dance without any emotional expression. It is characterized by its rhythmic patterns and complex footwork. It is the technical skill of the dancer which is showcased through nritta. Nritya, on the other hand, is an expressive dance that combines nritta with emotional expression. The dancer uses facial expressions, gestures, and body language to convey emotions, and to tell stories or express ideas.

The Indian Dancer

“Dance alone with rhythm and significance can express something of the occult or of the Divine as much as writing or poetry or art—why should it not and why should there be anything in it condemnable?”

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 27, p. 739

For an Indian soul, all human activity when done in the right spirit becomes a means for spiritual pursuit. This is true of dance also. Is it any wonder then Shiva, the greatest of all Yogis is also the Master of the Dance, the Nataraja? A brief glance at the sculptural depictions of dancers in Konarka or Khajuraho is enough to convince one of the sublime ecstasy that Indian dance is meant to invoke for both the dancer as well as the audience.

Dance in India has a rich tradition dating back to ancient times.

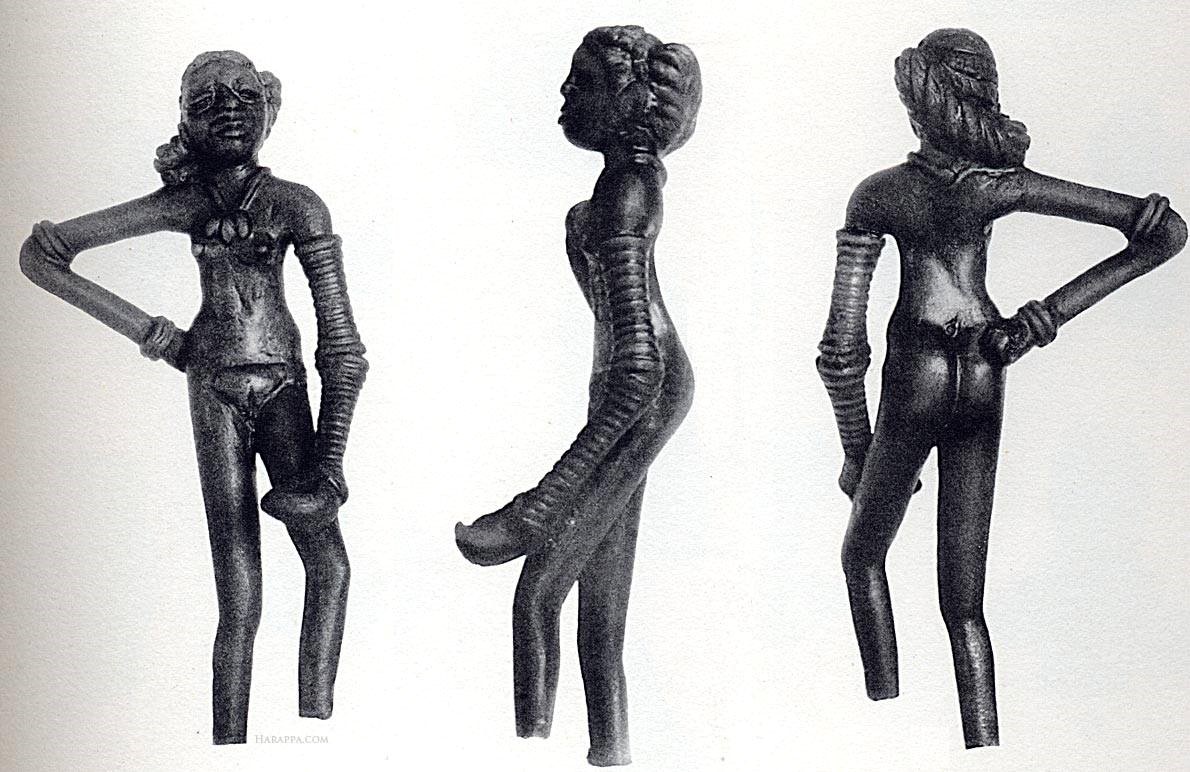

Excavations, inscriptions, chronicles, genealogies of kings and artists, literary sources, sculpture and painting of different periods provide extensive evidence on dance. Legends and myths from times immemorial support the view that dance has played a significant place in the religious and social life of the Indian people. A bronze statuette from Mohenjodaro and a broken torso from Harappa (dating back to 2500-1500 BCE) are suggestive of dance poses. The former has been identified as the precursor of the form of the Nataraja.

***

Who is an Indian Dancer? We find an answer in an inscription found at the 12th century Megheswara temple in Bhubaneshwar.

“…whose eye-lashes constitute the very essence of captivating the whole world, whose very gait brings about a complete stillness in the activities of the three worlds, whose bangles bejewelled with precious stones serve as unarranged candles during the dance, those deer-eyed maidens are offered in devotion to Him, Lord Shiva.”

Nandikeswara in the 6th century text, Abhinaya Darpana describes that a dancer or an actor must be capable, eloquent, self-confident and learned in the shāstras of various arts. He or she must be well-versed in song, instrumental music and dancing, of pleasing appearance, sweet speech, and quick wit. Other important qualities of a dancer include swiftness, composure, and expertise in grasping and releasing, emphasizing and relaxing the stress of emotion. The dancer must not be swayed by impulse, but be perfectly self-possessed. This is indeed a yogic quality.

Bharata Muni’s Nātyashāstra, the source book of the art of drama, dance and music is the earliest treatise on dance. The Nātyashāstra however does not treat dance as a separate category of art form. The term nātya broadly covers drama, dance and music, and dance and music are considered an inextricable part of drama.

The Integral Vision of Art

The term nātya is derived from the root nat (which means to act). The one who acts is a nata. By re-living the ‘life’ of the character, an actor presents before the spectators his interpretation of that character by means of dramatic art.

Nātya is a generic term broadly including drama, dance and music. According to Bharata, when the nature of the world possessing both the pleasure and the pain is depicted by means of representations through speech, songs, gestures, music, costume, makeup, ornaments etc., it is called nātya.

In ancient India, the arts of poetry, dance, music and drama, and even painting and sculpture were not viewed as separate and individualized streams of art. All art expressions were viewed as vehicles of beauty providing both pleasure and education, through refinement of senses and sense perceptions. The Nātyashāstra presents such an integral vision of art which blossomed in multiplicity. It claims that there is no knowledge, no craft, no lore, no art, no technique and no activity that is not found in the nātya. Drama was in fact considered the most comprehensive form of art expressions.

The interdependence of the arts was clearly underlined in another important text dealing with arts. Vishnudharmottara (circa 6th century) is an appendix to Vishnu Purāna. There, the idea was expressed in a famous passage in which sage Markandeya instructs king Vajra in the art of sculpture, emphasising that to learn it one must first learn painting, dance, and music.

The story goes as follows:

Vajra: O sage, teach me how to make the forms of gods so that the image may always manifest the deity.

Markandeya: He who does not know the canon of painting (citrasutram) can never know the canon of image-making (pratima lakshanam).

Vajra: Explain then to me the canon of painting because one who knows the canon of painting knows the canon of image-making.

Markandeya: It is very difficult to know the canon of painting without the canon of dance (nritta shastra), for in both these arts the world is to be represented.

Vajra: Explain to me then the canon of dance and then speak about the canon of painting, for one who knows the practice of the canon of dance knows painting.

Markandeya: Dance is difficult to understand by one who is not acquainted with instrumental music (atodya).

Vajra: O sage, speak to me about instrumental music and then speak about the canon of dance, because when the instrumental music is properly understood, one understands dance.

Markandeya: Without vocal music (gita) it is not possible to know instrumental music.

Vajra: Explain to me the canon of vocal music, because he who knows the canon of vocal music knows everything.

Markandeya: Vocal music is to be understood as subject to recitation that may be done in two ways, prose (gadya) and verse (padya). Verse is in many meters.

This tale clearly suggests that as per the ancient Indian vision of art, painting and sculpture without the knowledge of the drama and the dance would not have much depth. And that drama and dance, in turn, do require a knowledge of music and of the songs, which again is dependent on mastery over languages – both Sanskrit and Prakrit – with a thorough understanding of the elements of prose, poetry, grammar, meter, prosody etc. Such an integral vision of art is only possible when the cultural view of life is itself integral with God, Nature and Man being diverse manifestations of the One Supreme Reality.

From Dance to Drama…Continue reading in PART 2

~ Design: Beloo Mehra