Volume V, Issue 10

Author: Beloo Mehra

India had conceived the whole philosophy of her art, early on in the Vedic period itself, emphasises E.B. Havell in Ideals of Indian Art. The highest vision of the Vedic seers, the vision of the Infinite that is revealed and yet hidden in all the finite forms of the existence, materialised in the later periods in the wonderful forms of all Indian art.

An ear of mind withdrawn from the outward’s rhymes

~ Sri Aurobindo, Savitri, p. 273

Discovered the seed-sounds of the eternal Word,

The rhythm and music heard that built the worlds,

And seized in things the bodiless Will to be….

Our rishis tell us that at the origin of the creation was the primordial sound, Nāda Brahman. Therefore, a deep harmony and a rhythmic vibration hide in each and every atom in the universe. Harmony and music are inherent everywhere, in the heart of man, in the heart of nature, in the very heart of the existence.

Perhaps the heart of the God is forever singing. And who is listening to all the music that comes throbbing out to create the worlds? Let us hear from Sri Aurobindo as he sings in The Meditations of Mandavya:

A sudden silence and a sudden sound,

~ CWSA, Vol. 2, p. 514

The sound above and in another world,

The silence here; and from the two a thought.

Perhaps the heart of God for ever sings

And worlds come throbbing out from every note;

Perhaps His soul sits ever calm and still

And listens to the music rapturously,

Himself adoring, by Himself adored.

So were the singer and the hearer one

Eternally…

Such is the musical way our rishis have sung of the sṛṣṭi (srishti), the entire creation.

The Nātyashāstra, the ancient Indian encyclopedic text on Performing Arts, says that it was through the nāda, the primordial sound comes śruti (the interval). And from there the music begins. From śruti comes swara (scale), from swara the rāga (motif), from rāga comes gīta (song), and the soul of the gīta is nāda itself.

We find a similar idea in Brihaddeshi, another ancient text on Indian classical music (circa 5th to 6th century CE), attributed to Matanga Muni:

“There is no song without the nāda,

Nor music without it;

Without nāda there is no dance.

Indeed the whole creation itself is nāda.”

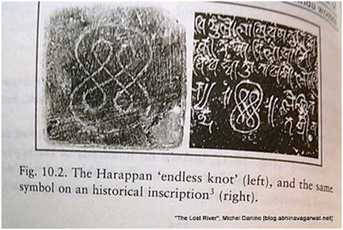

It is often said that Indian music emerged from a mythical past, a past before humans started recording history. Gods and goddesses were the makers of music then. Nāda Brahman is a vibration that fills the unmanifested void, featureless and undifferentiated, from which music emerges, embodied as Rāga. The Pranava Mantra, “OM”, is believed to belong to this category, a mysterious vibratory presence, the embodied creative power of the One.

For someone asking for a physical verification of such legendary past, the only reasonable and true response is that from the perspective of Indian ways of knowing, inner experience is an equally valid way to verify the truth. And the truths towards which inner experience points are always the same, regardless of the age. The Mother in her conversation dated October 27, 1962 speaks at length about the origin of music, in fact all arts, to be same as the plane of the gods. We also find Sri Aurobindo attributing the origin of all Music to the laughter of the Divine.

All music is only the sound of His laughter

~ Sri Aurobindo, Who, CWSA, Vol. 2, p. 202

All beauty the smile of His passionate bliss;

Watch: Sri Aurobindo’s poem Who

The Divine Laughter expresses the Divine Delight, Ananda; in fact all Beauty, says Sri Aurobindo is an expression of Ananda on the physical plane. Speaking of the origin of Art in India, E. B. Havell writes in The Ideals of Indian Art (1912) that India had conceived the whole philosophy of her art, early on in the Vedic period itself.

How was Art conceived? We may say that it happened when that wonderful intuition flashed upon the Indian mind that the soul of man is eternal and one with the Supreme Soul, the Lord and Cause of all things. The Rishis who expressed their spiritual realisations and experiences through the mantra-s and sang of the Spirit behind Nature in beautiful imagery were great artists. They gave to India monuments more durable than bronze.

Art in Material Form in the Vedic Period

“Indian architecture, painting, sculpture are not only intimately one in inspiration with the central things in Indian philosophy, religion, Yoga, culture, but a specially intense expression of their significance.”

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 269

Though in the Vedic period we may not find any explicit development of what we are accustomed today to call as the fine arts, nevertheless we must regard it as an age of wonderful artistic richness. Havell says that the transcendentalism of the essential Vedic thought could satisfy the intense reverence for the beauty and delight in Nature. And that is what the Rishis expressed through vivid images. In complete contrast to this, the barbaric materialism of today essentially negates all art and beauty.

It is also important to note that the Vedic period was not entirely barren of art in material form. The elaborate sacrifices and rituals called forth the highest skill of the craftsmen who worked on the yajñaśālā and the vedikā, the consecrated space and altar for performing the sacrifice ritual. We find relevant references in several texts from Vedic and post-Vedic times. For example, in the Ramayana we find a description of the great yajña which Rishi Vasishtha had organized. And we find there equal honour being accorded to the skilled craftsmen who prepared the yajñaśālā.

***

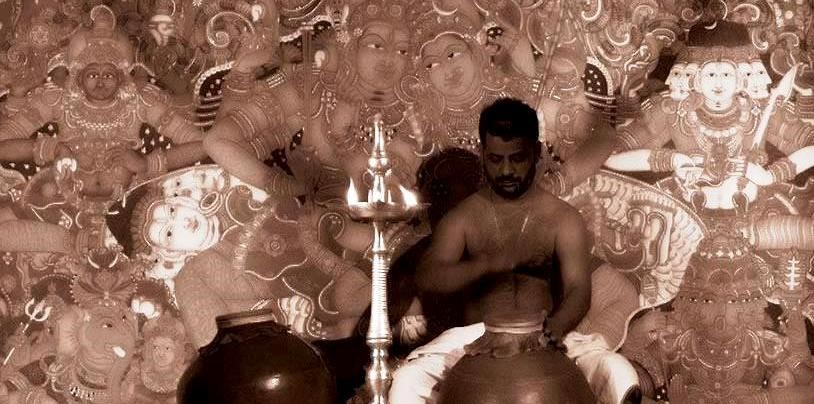

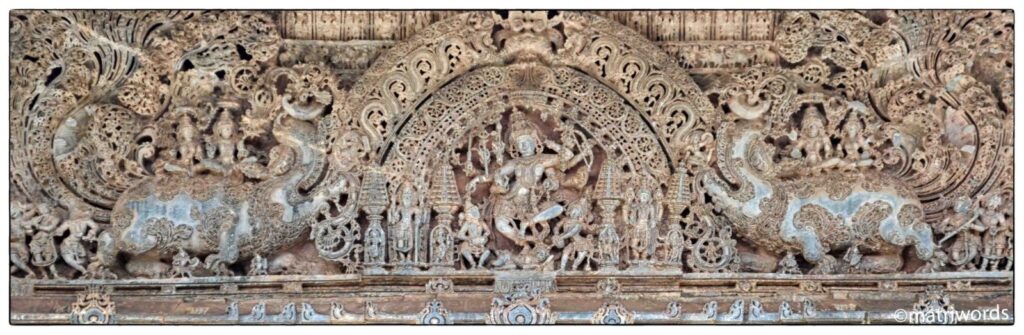

There is a direct continuity between the ornamentation of carved posts made for yajñasthala and the ornamented pillars of later Hindu temples. The priests who performed the yajña and recited the mantras were experts in poetic meter and precise articulation, pronunciation and accent. This precise musicality of the ritual and its inner significance of facilitating an invocation and a transcendence – both for the singer as well as the listener – may be considered the highest form of art in itself. The entire performance of a ritual in itself is an Art as it emphasizes the deep inter-connectedness of Art, Religion, and Life.

Significance of Adornment, Decoration

Indian Tradition considers alaṃkāra (or alankāra), adornment and decoration auspicious and leading to prosperity. We find evidence in various texts such as Śilpa-shāstras and the purānas. Society considered decoration important for the houses – both of gods as well as ordinary people.

The Vishnudharmottara prescribes auspicious depictions on houses of men. There are also prescriptions for which specific depictions to avoid. The Samarangana Sutradhara speaks of ashtamangalas (eight auspicious objects) on the door. It says that the auspicious Sri is to be carved on the entrance. The Pramanamanjari, a śilpa shāstra from Western India, speaks about the kind of decorations for the pillars in houses. For example, it recommends use of figures in dance-poses, and decorating the threshold with flowers and leaves.

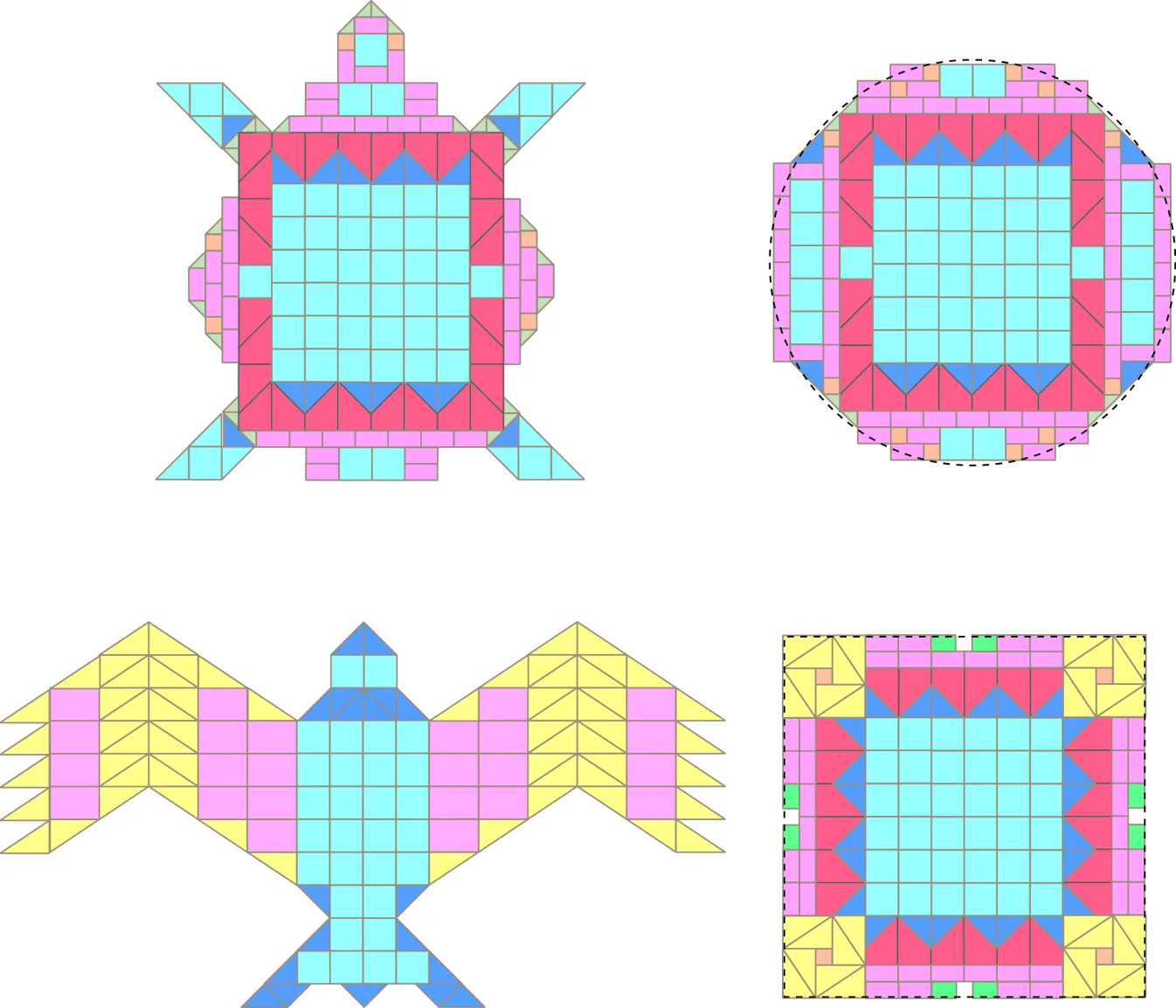

This tradition of decorating the houses continues to this day in the form of kolam, rangoli and mandala. Much study has gone into the deeper meaning behind these sacred practices. The noted expert on Indian art, Stella Kramrisch commenting on the power of life giving mandalas writes:

“The magic diagram makes it possible for power to be present and it brings this presence into the power of the person who has made the diagram…

“Here it is the magic circle, in other designs—the sacred square, a concatenation of curves, or intersection of polygons—that encloses the magic field. Into it the power of the god is invoked. It is assigned to its enclosure, it is spellbound. It cannot escape; it is controlled. It is held in its confinement, bound in a plane by the outline of the enclosure so that it cannot escape into the ground where like lightening, it would be rendered impotent.”

~ Exploring India’s Sacred Art: Selected Writings of Stella Kramrisch, pp. 106-107

***

Bharata’s Natyashāstra, which is based upon the Gandharva Veda (appendix to Sama Veda) also speaks of the significance of sacred adornment. The third chapter gives detail of the rang-pooja to be performed to the gods of the stage before enacting the drama. A mandala should be drawn on the stage. And the gods are invoked to occupy their proper seats to be worshipped. In another ritual mentioned in the Natyashāstra, a brilliant mandala of ashtadala padma is drawn. And Brahma and other guardian deities of the eight quarters etc. are invited and worshipped.

Indian Art – an Expression of the Divine

“The whole basis of Indian artistic creation, perfectly conscious and recognised in the canons, is directly spiritual and intuitive.”

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 257

The deep connection between Indian art and sacred ritual, right from the Vedic yajña, continues till today in myriad forms of temple worship. The outer ritual of yajña may be seen as a sacred theatre engaging all the senses. And it facilitates a revelation or a realization or a moment of transcendence. Such experience is also possible when one stands before a great work of art.

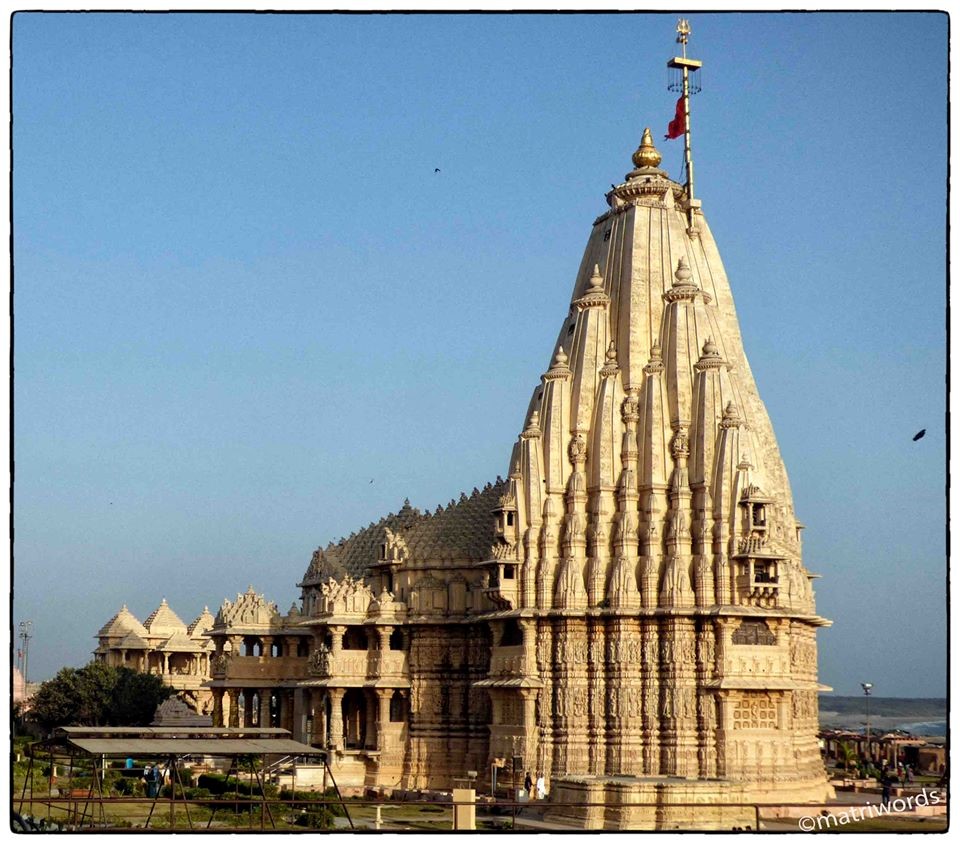

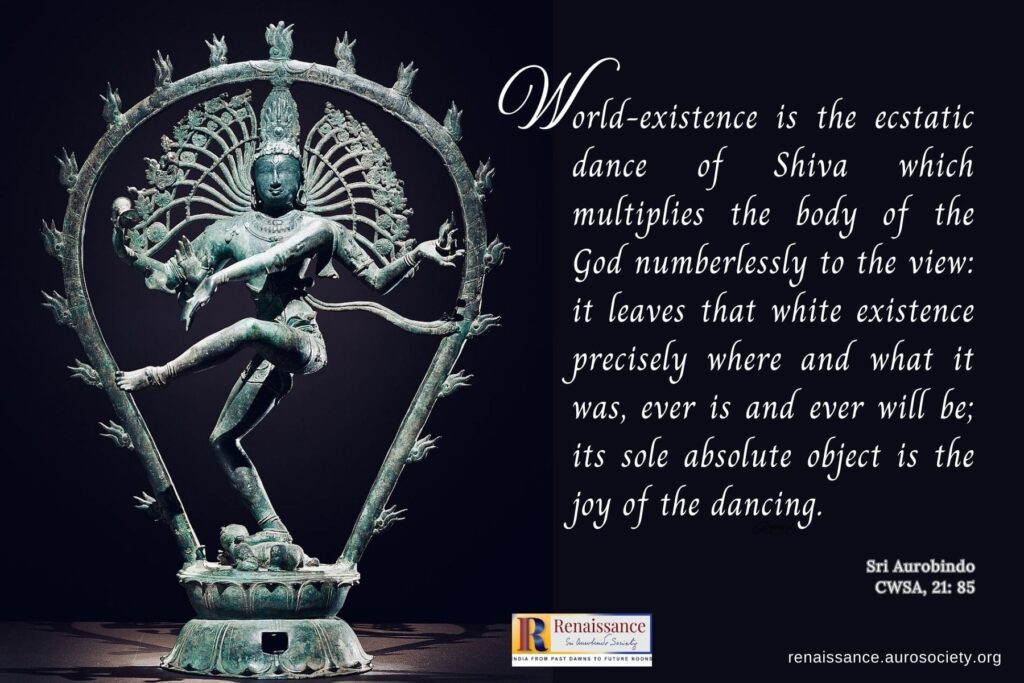

The great temples of India are magnificent works of art. And so are the countless sculptures that make the temple — inside and outside. And there are also the performances of dance and music in their nātyamanadapa-s, and the murals that adorn its walls.

***

Art in India has thus not been separated from the Divine, just as the Divine is not separate from the individual. In the West today, one finds the best art in the sterile atmosphere of a museum or a gallery. But to this day the best of Indian art is to be found in the great temples of India. Sri Aurobindo emphasises that the greatness of Indian art is, in truth, the greatness of all Indian thought and achievement. He points out a few specific points when speaking of this greatness:

- recognition of the persistent within the transient,

- recognition of the domination of matter by spirit,

- the subordination of the insistent appearances of Nature (Prakriti) to the inner reality which, the Mighty Mother of All Creation veils in a thousand ways even while she suggests.

***

READ:

“In India God is the All-beautiful” – Conversations with Sri Aurobindo

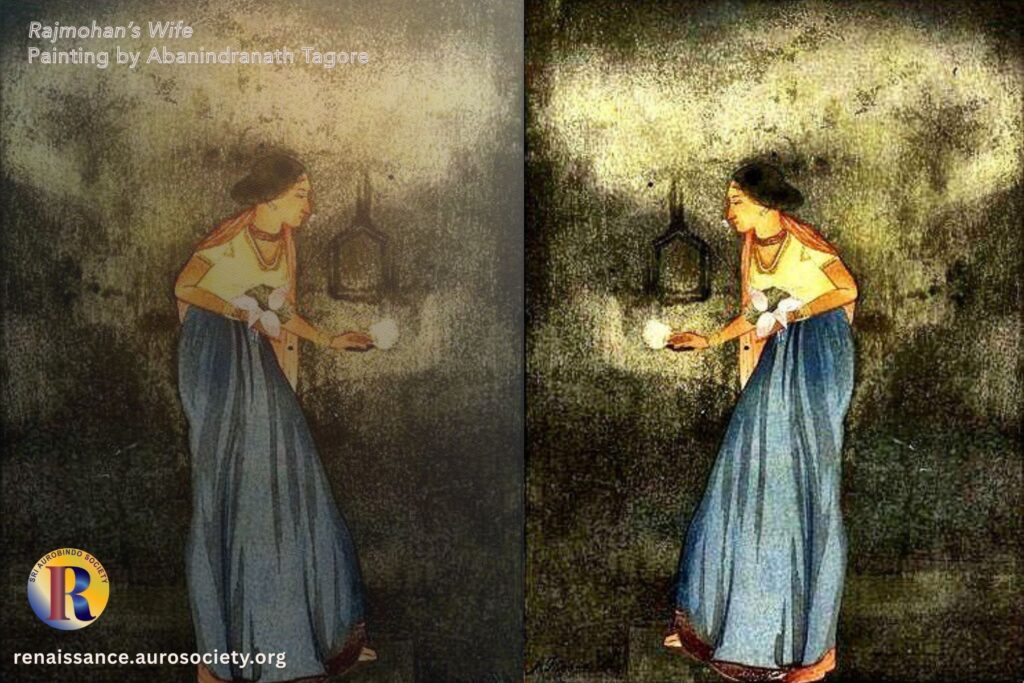

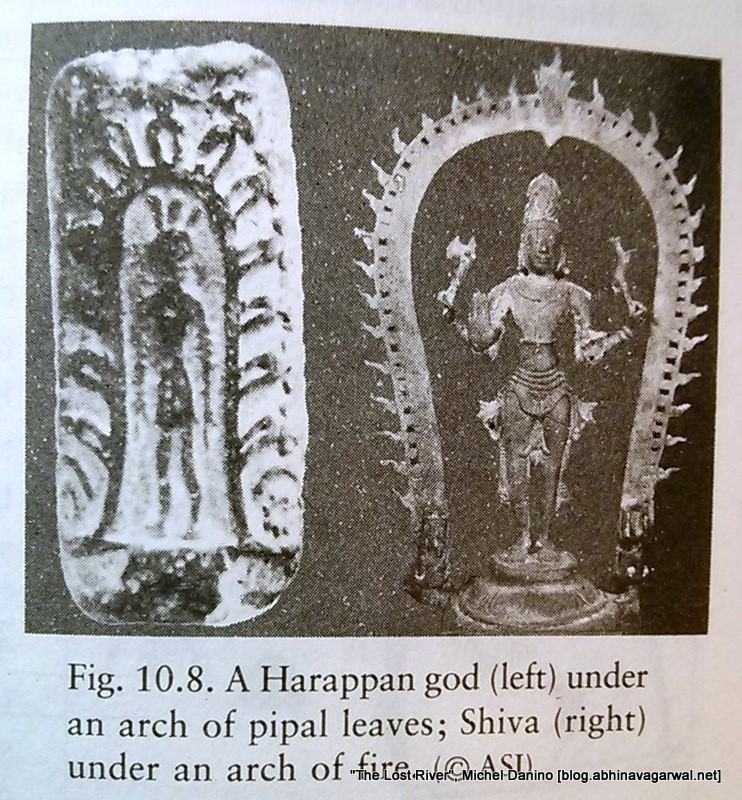

The highest vision of the Vedic seers, the vision of the Infinite that is revealed and yet hidden in all the finite forms of the existence, materialised in the later periods in the wonderful forms of all Indian art. This includes painting, sculpture, music, dance and more. Hindu and Buddhistic art, Sri Aurobindo says, have been very largely a “hieratic aesthetic script of India’s spiritual, contemplative and religious experience.” And this is why, he speaks that the highest purpose of the great Indian art is to disclose something of that highest experience.

“Its highest business is to disclose something of the Self, the Infinite, the Divine to the regard of the soul, the Self through its expressions, the Infinite through its living finite symbols, the Divine through his powers. Or the Godheads are to be revealed, luminously interpreted, or in some way suggested to the soul’s understanding or to its devotion, or at the very least to a spiritually or religiously aesthetic emotion.”

~ CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 267

***

Offerings in the Current Issue

The highest Indian art is identical in its spiritual aim and principle with the rest of Indian culture, emphasizes Sri Aurobindo. From where does such art originate? We find some important hints in two short essays by M.P. Pandit (Commentaries on the Mother’s Ministry, Vol. IV). In the first one, we learn of the various zones of what the Mother called as the World of Creation. This helps us understand about the source of inspiration for various art forms. The second essay emphasises that art is way to help reveal and experience the subtler order of existence. And in this way, art can be an important means for spiritual progress.

The Different Paths of an Artist and a Sadhu features a masterly essay by Nolini Kanta Gupta. It speaks of two key points: what is the purpose of art; and what is the rightful place of spirituality in art.

The 2-part essay titled The Rapture of the Cosmic Dance focuses on the sacred origins of dance and drama as per the Indian cultural tradition. In part 1, read about the legend concerning the beginnings of dance as a sacred art. Also emphasized here is an integral vision of art in India. Part 2 highlights the legend behind the sacred origin of Nātya or drama in Indian cultural tradition. The focus of drama in India was almost always along the lines of the Indian view of life. This view emphasised continuity and renewal of life, cyclical nature of life, as well as the human urge to create an ideal life.

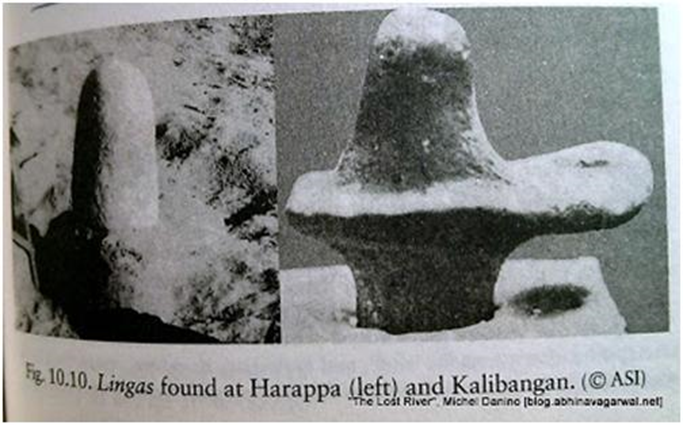

Jishnu Guha, a new member of the Renaissance author team, takes sweeping look at the history of Art in India and emphasizes the ‘sacred’ and the ‘spiritual’ foundation of all artistic creation in India. We feature Part 1 of his essay which focuses primarily on a brief history of sculptural art in India.

Sri Aurobindo writes in The Human Cycle,

“The art, music and literature of the world, always a sure index of the vital tendencies of the age, have also undergone a profound revolution in the direction of an ever-deepening subjectivism. The great objective art and literature of the past no longer commands the mind of the new age.”

CWSA, Vol. 25, p. 30

We find two beautiful examples of such art and literature in the offering by Sudha Prabhu titled Embracing Life in Its Many Colours and Hues. Both these examples speak of the artist’s inner experiences. The focus is on connecting at a deeper level with the colours, the meanings hidden in the subtle vibrations of different colours, all emerging from a subjective perspective.

We continue with Part 2 of V.K. Gokak’s essay on Rasa: Its Meaning and Scope. Here he delves into the questions — is there a primary rasa from which other rasa-s originate? In what way is rasa an attribute of the soul?

In the Book of the Month feature, read an excerpt from a writing by Stella Kramrisch on the sacred art of dhūlichitra. The art of dhūlichitra finds a mention in several ancient Indian treatises on art. These include Vishnudharmottara, Silparatna of Srikumara, and Abhilashitartha Chintamani of King Someswara III. Dhūlichitra are images or paintings or drawings executed with dry and wet powders or paste on floors, known by many names such as kolam, rangoli, alpona, mandana, etc. Kramrisch speaks of these as ‘magic diagrams’.

We hope our readers will enjoy going through the various offerings in this issue. As always, we offer this work at the lotus feet of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother.

In gratitude,

Beloo Mehra (for Renaissance Editorial Team)

~ Design: Beloo Mehra