Volume III, Issue 1

Author: Barindra Kumar Ghose

Editor’s note:

The month of January brings birthdays of several key figures in Indian history – Swami Vivekananda, Subhash Chandra Bose and Dilip Kumar Roy to name a few. Another important name in this list is Barindra Kumar Ghose, known more popularly as Barin Ghose. Born on January 5, 1880, Barin was Sri Aurobindo’s younger brother, and a great revolutionary in the Swadeshi movement. He became a national hero because of the role he played in the Jugantar movement and the Alipore Bomb case. It is unfortunate that his name somehow remains unsung in the annals of history of Indian freedom movement.

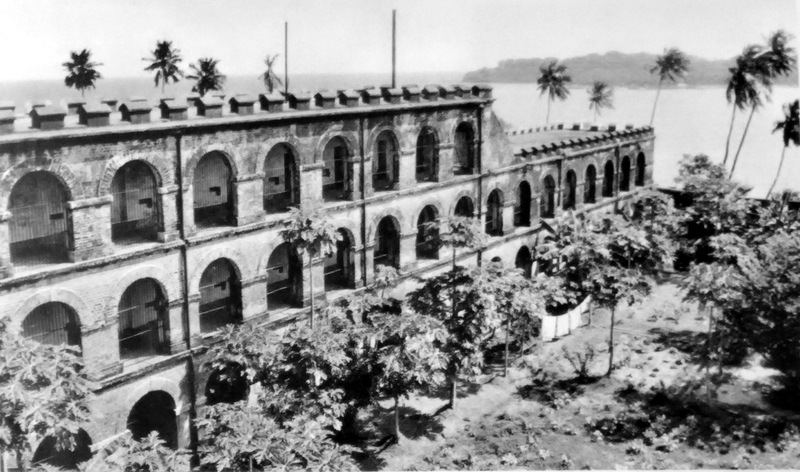

For our Book of the Month feature, we bring for our readers last chapter of the book ‘The Tale of My Exile‘ by Barin Ghose. This book is a record of his hard imprisonment at the dreaded Cellular Jail at Andamans.

Originally written in Bengali with the title ‘Dwipantarer Katha‘, the book was first published in 1920 by Arya Publishing House in Calcutta. It was translated into English by Nolini Kanta Gupta. It is very likely that Sri Aurobindo had seen this book. The book had been out of print for nearly a century, until 2011 when it was published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department. In the Introduction chapter to this edition, Sachidananda Mohanty writes:

“Written in a style evocative and deeply moving, The Tale of My Exile would easily rank as one of the most outstanding prison narratives to emerge from the subcontinent in the early twentieth century. One is surprised that this book has not had many reprints. Part of the reason for this glaring omission could be traced to the lackluster manner in which the Indian nation has treated its freedom fighters, the forgotten heroes, especially those who fought an armed freedom struggle. The legacy connected with Sri Aurobindo has not fared well either. A change in the historiography from the nationalist to the Marxist could be a possible factor for eclipsing the history of the militant freedom struggle.” (pp. xi-xii)

Also see this video lecture:

Sri Aurobindo, the Revolutionary Nationalist

As the preface to the 2011 edition reminds the readers, The Tale of My Exile is an important historical document that has a great deal of contemporary value. It illuminates our understanding of a forgotten chapter of the national freedom struggle and brings to light the untold suffering of the freedom fighters who were imprisoned in the dreaded Cellular Jail in the Andamans.

The last chapter of the book, featured here, gives us a peek into Barin Ghose’s state of mind and overall psychological attitude during the course of his tough imprisonment. Headings have been added by us for ease of readability in this digital presentation.

Chapter XII – A Personal Word (Part 1)

Our friends and relatives are certainly anxious to learn how we all passed our days of grim calvary in the Andamans. But it is not possible for any single man to know and tell the inner history of so many minds. So I will speak of myself only and that may perhaps incidentally offer a glimpse into the secret movements of other hearts that suffered the same sorrows and shared the same pains.

I was in a state of sweet self-intoxication, almost beside myself in a sort of overwhelming beatitude, when I was counting my last days, with the halter round my neck and shut up in the “condemned cell.” I was then face to face with Death, and alone and away from the world, I was playing with it most amorously and trying to snatch the veil of the beloved one. For Pain, its messenger, had already whispered into my ears, “Behind that dark veil there is the most radiant and soul-entrancing beauty.” So the more I was bent upon tearing off her covering, the greater was the obstinacy of my beloved to disclose herself.

“A thousand confusing emotions”

You will perhaps ask me, “Were you not afraid of death?” Indeed I was and it was therefore that tears flooded my eyes, through all that sunshine of happiness, when I listened to the order of hanging. It seemed to me that this time God was going to take away by force everything—my soul and mind and body—what I could not in any way give up to Him.

It was ever my lot to harbour in my bosom the ragings of a thousand confusing emotions at the same time. I was shaking in fear, my heart was beating fast and yet a delight of entire consecration welled up into tears. My sorrow-stricken and prostrate heart was lamenting,

“O God of Love and Beauty! I yearn for the touch and smell and sight of thy infinite playthings of this world. Do not put out the light that yet brightens my earthly home. I shall not find relief in death, for now is my time of sweet honey-moon. The hour is not yet come when my insatiate desires would have found repose in thee and when dying would be sweet with thy Presence transfused in my soul.”

And my soul at the same time, full of renunciation and ascetism, in a yogic equanimity, chanted in an opposite strain,

“As bubbles of water rise out of water and die down in water even so the mind melts away in nothingness.”

“A sombre funeral and a joyous festivity”

It was, as it were, that the same house witnessed at the same time a sombre funeral and a joyous festivity. I do not know if anybody else had a similar experience, but thus it was with me.

Life demanded me still and so one day I learnt that my death sentence had been commuted to transportation and that I must give up hoping for death and prepare myself rather to be buried alive. Then the curtain lifted again over a new enactment of life’s double strain of pleasure and pain on the stage of the Andamans.

Those who dwell in pleasure and seek pleasure most certainly feel an unbearable pain if all on a sudden a crash and catastrophe befalls them. Their whole soul cries out for the happiness that is no more. But the calamity that struck us down was of our own making. It was we ourselves who opened the way for the evil and in a way welcomed it. A pain that we invited on ourselves, however lacerating, could not naturally overwhelm us. The more we suffered, the more it made us smile.

The course of true love is never indeed smooth. The dangers and difficulties of the way lend an added zest to the venturing spirit. And yet pain is pain and we felt the suffering. No doubt, we were free-lances, though without the lance, but we were creatures of flesh and blood.

“The real editors or writers of Yugantar (for there was no declared editor) were Barin, Upen Banerji (also a subeditor of the Bande Mataram) and Debabrata Bose who subsequently joined the Ramakrishna Mission (being acquitted in the Alipur case) and was [ ] prominent among the Sannyasis at Almora and as a writer in the Mission’s journals. Upen and Debabrata were masters of Bengali prose and it was their writings and Barin’s that gained an unequalled popularity for the paper.”

(Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 36, p. 77)

Want of Company – The Greatest Sorrow

Our sorrows were many. The greatest of them was the want of company. The orders were strict that we should not talk to each other, even though we might be close together and in the same block. What a wail we smothered in our hearts when we walked together, eat together and worked together and yet could not open our mouths!

We could indeed steal glances, whisper a half-uttered word now and then, but all that served only to increase our suffering. Whenever we were caught unawares in our unlawful conversation. Uncle Khoyedad thundered out, “you Bengalees, be a bit modest!” It was a task, indeed, always to be “modest” in this way. We accused the gods and chafed and murmured within,

“This is not what we expected. We admit that we rushed to the deliverance of our country, but is that a sufficient reason that we should be ever confronted with the grimaces and threats of these whiskered Kabuli duennas? And who the deuce possesses such an infinite fund of modesty as to be able to draw upon it interminably at a moment’s notice every now and then?”

As if we were no better than the living baggage that is known in Hindu Society as the divinely modest and obedient and devoted consort! Could the fates be more perverse? That was how we first experienced the woes and terrors of the Purdah.

The Food Difficulty

The food difficulty was not so very painful in the beginning. But as days wore on, the dismal monotony of the same dish every day — rice and dal and kachu leaf — began to tell upon our nerves.

The farther we left behind the atmosphere of the motherland and the more we inhaled the air of the Andamans, the greater was our repulsion to food and the keener our discomfort. It was the mere sense of duty and the cruel necessity of hunger that made us eat. The amount of moderation and control that we achieved was a thing certainly to be coveted even by the Yogis.

Poor famine-stricken India also might have taken a wholesome lesson from our example. It is said, that the cow of a Brahmin eats very little but yields plentifully both milk and dung. We too were something belonging to the same category. A prisoner eats little but toils quadruple-fold.

The daily ration per meal is as follows — rice 6 oz., flour for roti 5 oz., dal 2 oz., salt 1 dram, oil 3/4 dram and vegetables 8 oz. No distinction is made here between prisoner and prisoner. A ravenous giant like Koilas and a grass-hopper like me were both given the same quantity of food.

“Hunger is the best sauce.”

The only hopeful feature of the situation was that one did not require much eating in this country. A few days communion with the air and water of Port Blair is sufficient to uplift you to the supreme stage of dyspepsia. And whatever hunger and desire are left, disappear altogether when you know of the marvellous banquet that awaits you! So one can easily imagine what a delight it was for us to get, after a year or two of the same old routine, any variation in the shape of sweets or something else however trifling.

One day a Pathan warder, Sayad Jabber by name, while on duty at night, brought me secretly a dish of meat. I do not know whether any food prepared by the famous Draupadi herself, could have been as savoury as that dish, with such a gusto did I devour it.

Another day a veteran convict named Charlie gave me to eat ordinary roti smeared with sugar and fresh coconut oil. I can say quite honestly that even the mihidana of Burdwan never tasted to me so sweet.

After the life of suffering and want that we led in the Andamans the lot of the rich rolling in luxury and surfeited with daily banquets appeared to us really pitiable. There are none else who have been so cruelly deprived of the joy of the palate. Even kings do not know the heavenly delight that a pauper feels when in the midst of his life-long misery he gets an occasion or two to taste a dainty dish. Hunger is the best sauce — that is a simple truth that is always true.

CONTINUED IN PART 2

~ Design: Biswajita Mohapatra and Beloo Mehra