Volume V, Issue 11-12

Author: Beloo Mehra

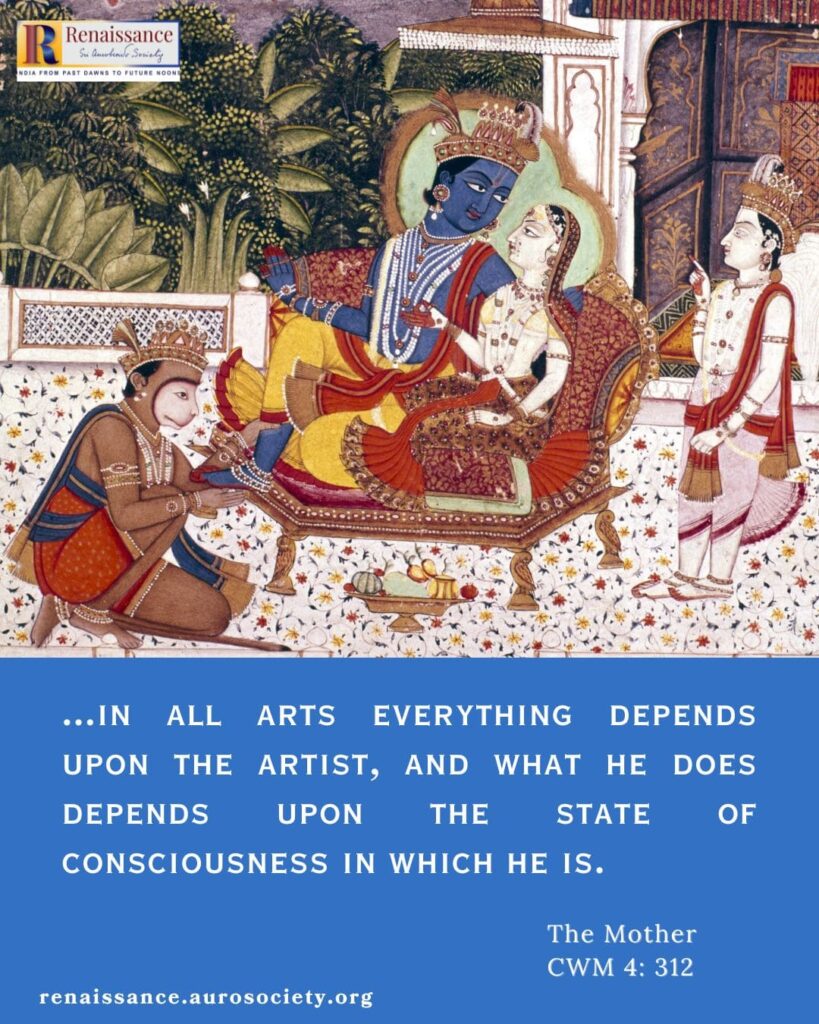

…in all arts everything depends upon the artist, and what he does depends upon the state of consciousness in which he is. A sculptor may be an extremely spiritual man and his production extremely spiritual also, if he knows how to express his experience. And a poet can be quite a commonplace materialist if he does not receive his inspiration from a higher state.

~ The Mother, CWM, Vol. 4, p. 312

All art has one ultimate basis, but the ideas and forms that the creative spirit takes are many. This is what gives each manner of art its own ideals, traditions and agreed conventions. This is not only true of different art forms, but also arts from different cultures. E.B. Havell once said that it is a serious mistake to interpret or critique art that is created in a certain cultural context without understanding the underlying philosophical basis of the culture’s highest view of existence, life and creative pursuit.

In the Indian vision, all Art is a medium to express the Ananda, this Eternal Delight through form. A quintessential Indian painter or sculptor seeks the pure intensities of delight as he searches for the universal beauty revealed or hidden in all creation. As he seeks perfection in the form that comes through his hand or brush, his inner being experiences a sort of enlightenment through the power of a certain “spiritually aesthetic Ananda”, reminds Sri Aurobindo (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 302). He continues,

The Indian artist lived in the light of an inspiration which imposed this greater aim on his art and his method sprang from its fountains and served it to the exclusion of any more earthly sensuous or outwardly imaginative aesthetic impulse.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 303

Who is an Artist?

Before we proceed further, let us ask a fundamental question — who is an artist? When the Mother was asked this question, her reply was:

If you ask me, I believe that all those who produce something artistic are artists! A word depends upon the way it is used, upon what one puts into it. One may put into it all that one wants.

~ CWM, Vol. 5, p. 324

She then proceeded to give an example of gardeners in Japan who spend their time doing all kinds of trimmings to correct the forms of trees so that in the landscape they make a beautiful picture. With the help of special props, they give trees special forms so that each form may be just what is needed in the landscape. Great care and attention are paid to where the trees are planted so that they will go well with the whole set-up. The Mother says that such gardeners are no less than any artists because they have a keen perception of harmony.

All those who have a sure and developed sense of harmony in all its forms, and the harmony of all the forms among themselves, are necessarily artists, whatever may be the type of their production.

~ The Mother, CWM, Vol. 5, p. 324

In a letter to a disciple, Sri Aurobindo explained that a real artist, one who has “the spirit of artistry in his very blood” will certainly be artistic in everything he does (CWSA, Vol. 27, p. 676).

An Artist and a Craftsman

In India all art, all knowledge, all creative work, all existence is an expression, a manifestation of the Divine. The world is a symbol of the Brahman, the Supreme Existence, says Sri Aurobindo. All artists and artisans trace their lineages back to the supreme creative principle, the Vishwakarma, the name given by the tradition to “the maker of the universe”. If such is the view, then any difference between ‘fine art’ and ‘folk art’ — a distinction generally made by the academically oriented westernized mind — is meaningless. Similarly, who is an artist and who is a craftsman or an artisan also becomes a moot point as far as the sacredness of all artistic pursuit and creative activity is concerned.

Yet there is something that distinguishes an artist’s temperament with that of a non-artist. It is not merely about having a greater imagination, because as per the Indian view of art, imagination is merely an instrument to express what is received from a higher source of inspiration. It is also not only about having received the necessary skill and training in the particular form of art, though that is important.1

It is quite usual for poets and musicians and artists to receive things—they can even be received complete and direct, though oftenest with some working of the individual mind and consequent alteration—from a plane above the physical mind, a vital world of creative art and beauty in which these things are prepared and come down through the fit channel.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 27, p. 15

The Mother once explained that the true value of one’s creation depends on the origin of one’s inspiration, on the height where one finds it. But the value of the execution however, depends on the vital strength which expresses it. A genius is one who has both — opening to high inspiration and the vital executive strength to express that inspiration, which is very rare. “Generally it is the one or the other, more often the vital,” she went on to add. (CWM, Vol. 5, p. 75)

Often the more “popular art” is popular precisely because it is an expression of a powerful and strong vital. The commercial spirit of the age makes such art even more appealing. Often what is missing in such expressions is the vision.

The Inner Seeing

An ability to ‘see’ is the key difference between a true artist and a non-artist or a mere craftsman. We are not talking here about the specific angle or perspective from which an artist sees the outer form of the object which he or she is expected to draw, paint or carve. The concern is with the ‘inner seeing’ or the subtle seeing of the truth that hides within the object or behind its outer form and name which the artist is supposed to grasp and express.

This ability to ‘see’, this drishti, may be a gift of the Nature, but it still requires cultivation and refinement through a rigorous training and discipline. This discipline also includes the necessary inner purification and quietening so that the opening to the higher source of inspiration can be strengthened and kept turned upward.

Speaking of the form of the Vedic hymns, Sri Aurobindo remarks that the finished metrical form, exhibiting great subtlety and richness of poetic style, reflects a supreme and conscious Art. The Vedic tradition speaks of the Rishis not as the individual ‘composers’ of these hymns, but as the ‘seers’ and ‘hearers’ of the spiritual truth which find an expression in the hymns rising out of their very soul.

READ:

Art, Spiritual Progress and the World of Creation

The Vedic Rishi was, however, not concerned about the hymn as a work of poetry. Rather, the art of expression to him was mostly a means, not an aim. The principal preoccupation of the Rishi was “strenuously practical, almost utilitarian, in the highest sense of utility”, says Sri Aurobindo.

The hymn was to the Rishi who composed it a means of spiritual progress for himself and for others. It rose out of his soul, it became a power of his mind, it was the vehicle of his self-expression in some important or even critical moment of his life’s inner history. It helped him to express the god in him…

~ CWSA, Vol. 15, pp. 11-12

From a spiritual view, true art is an expression of the Divine in life and through life. This necessitates that the artist — the painter, the musician, the poet, the sculptor — must first have a unique, personal contact with the Divine. And then express this contact through the art form the artist has mastered — in a style and form unique to him. This makes the art ‘individualistic’ but not rooted in the ego. This makes the art ‘impersonal yet personal’ in the true sense of both the terms.

Offerings in this issue

The above discussion presents some of the key ideas explored in more detail in the current issue. The last two issues explored topics related to The Purpose of Art – From Beauty to Bliss (September 2024) and The Sacred Origins of Art in India (October 2024). We now move to an exploration of two inter-related themes: “The Way of the Indian Artist” and “Art as Yoga.” Given the great importance of these topics, we have made this a double issue with 18 offerings. (A bonus offering will be released on Siddhi Day, November 24).

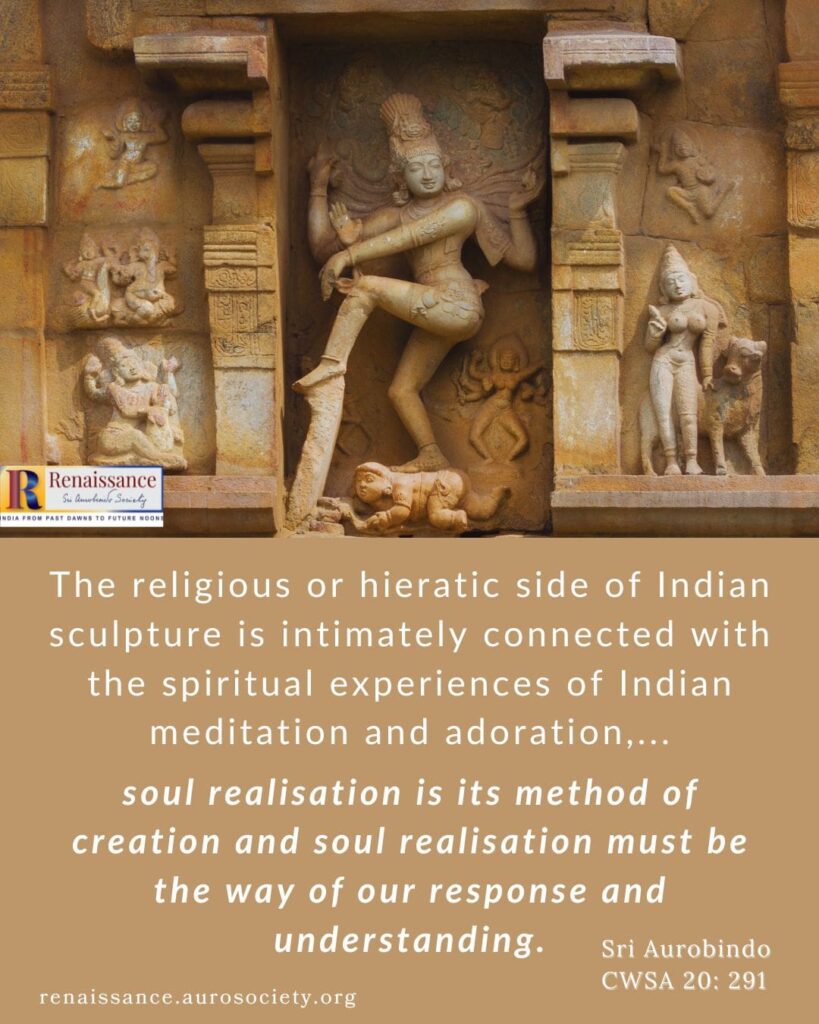

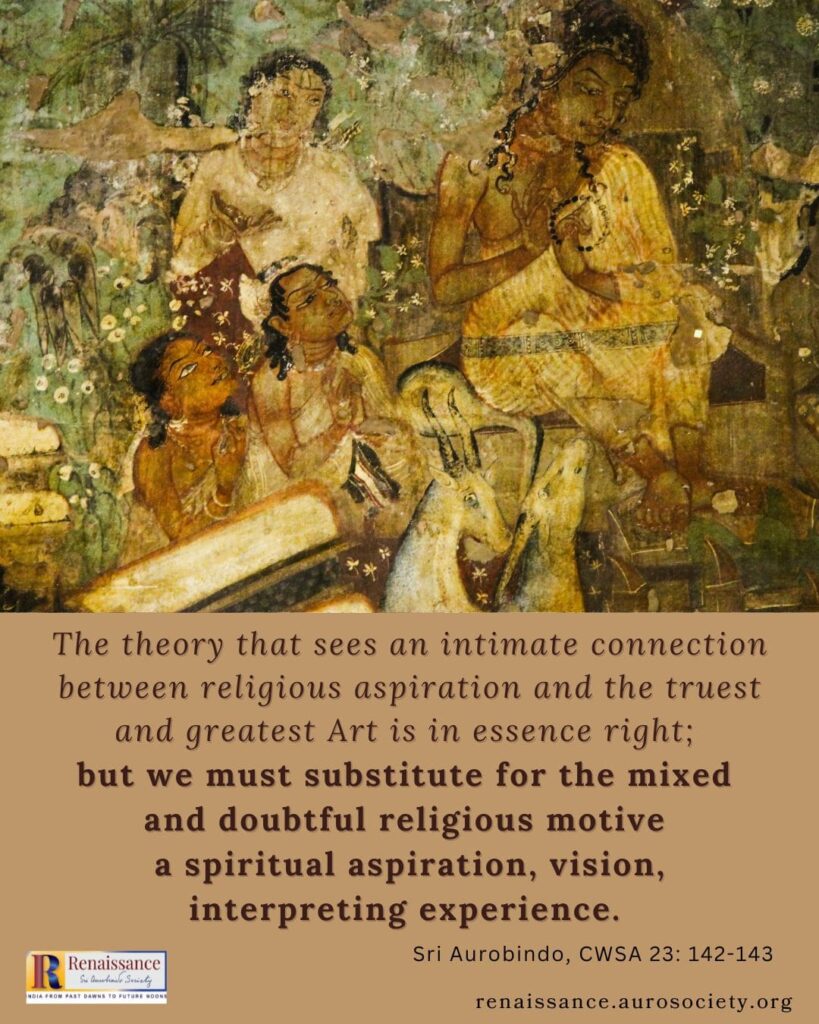

We begin with a 1909 essay of Sri Aurobindo in which he describes what is unique about the origin of the greatest art in India. Here he also summarizes succinctly the essential difference between Western and Indian views of artistic creation. Also read some selections from Sri Aurobindo and the Mother which help us understand how soul-realisation is the characteristic method of the Indian artist.

We also feature a conversation of the Mother where she gives a detailed explanation of the relation between Art and Yoga. She speaks of various art forms as well as the changes in the conception of art over time, and gives relevant examples. The Artist as a Yogi and the Yogi as an Artist — both these aspects are wonderfully explained. In this 2-part feature, also read the Mother’s explanation of the phenomenon of mushroom art where art becomes disconnected with life and is no longer an expression of integral harmony and beauty.

In the feature titled “Creation is a misnomer; nothing in the world is created” Beloo Mehra gives an overview of what constitutes an ideal artist as per the Indian cultural tradition. In the concluding part of our ongoing series on Rasa: Its Meaning and Scope, V.K. Gokak reminds that an artist is one in whom the sattwic buddhi or the capacity for ideal sensibility predominates.

The Great Impersonal Creators

The Mother once said that true art must be an expression of the Divine in life and through life. It is because of an intimate relation of great art with Life, that certain literary and artistic works feel so ‘alive’ even after thousands of years when they were first composed or carved or painted. Their distinct living quality makes them relatable and fresh across time and context.

Sri Aurobindo helps us find a valuable insight into why this is so. These works of art were the outpourings of poets and artists who had the power to become one with all that was around them. These creators were complete, vast, multitudinous, infinite in a way, impersonal & many-personed in their very personality. They were “not divine workmen merely but true creators endowed by God with something of His divine power and offering therefore in their works some image of His creative activity.”

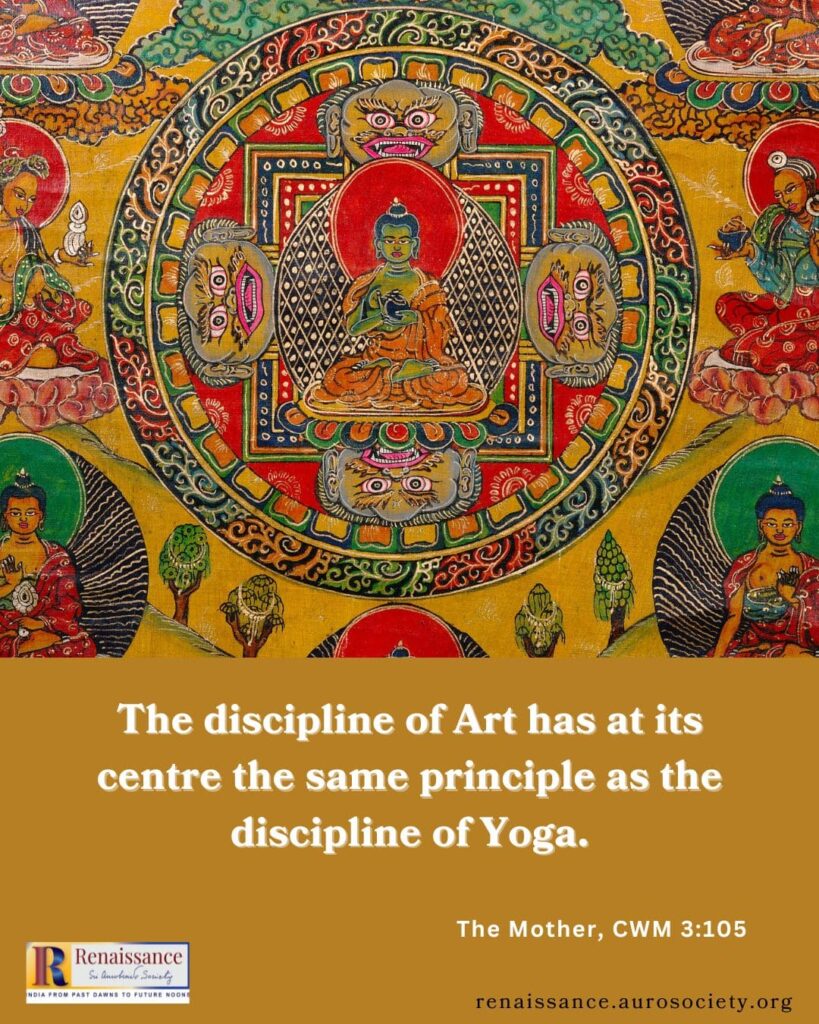

Read our feature titled The Great Impersonal Creators and Their Living Creations to find out what makes them “true creators” and explore the relation of Art and Yoga. These passages also help us reflect on the Mother’s words: “The discipline of Art has at its centre the same principle as the discipline of Yoga.”

Integral Yoga and Artistic Pursuit

We feature some excerpts from Sri Aurobindo where he explains the right Yogic attitude one must have towards artistic pursuit in the path of integral sādhana. The first excerpt is from The Synthesis of Yoga where he emphasises on all works, including all the artistic and creative works, to be done as an offering to the Divine Shakti within. Only then they are helpful as means to spiritual realisation.

The second passage is from one of his letters to a disciple. Here Sri Aurobindo reminds that everything can be turned into a means of realisation of the Divine. But much depends on the consciousness and attitude with which the work is pursued.

In a 2-part feature we highlight excerpts from a lecture delivered by A. B. Purani at the J J. School of Art, Bombay (now Mumbai), on February 1, 1954. Our focus is on those sections in particular that speak of the art-creation processes. The first part goes into describing some of the distinctive aspects of artistic tradition in India. And the second part is where the author focuses on the future art of humanity. He also summarises the many planes of consciousness to which an artist can ascend through yoga.

Monica Chand and Egle J. Raie Dey are co-founders of YogArt, an organization dedicated to giving practical form to the Mother’s teaching that essentially “the discipline of Art has at its center the same principle as the discipline of Yoga”. Read all about their work in this issue.

Art, Music and Poetry

Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy is a familiar name for every student or rasika of Indian Art. He is widely acknowledged as one of the great art historians and scholars of Indian art. Coomaraswamy was an early interpreter of Indian culture to the West. With this issue we serialize a comprehensive essay on Indian Art by Ananda Coomaraswamy. We bring 2 parts in this double issue, and the other three will be presented over the next 3 issues. This essay was first published in 1908 by Essex House Press in a limited edition.

We also feature a selection from Rabindranath Tagore where speaks of the wholeness of Music. It is the purest form of art because the music and musician are inseparable, he says. Narendra Joshi joins our team of authors from this issue. In his debut article titled Art, a Passage for Higher Life, he reminds us that the Indian vision which integrates life, culture and art acknowledges and celebrates the value of Art as a means to refine one’s nature and prepare for a higher life, which is also the true meaning of culture.

We invite the readers to enjoy two poetic contributions by Sudha Prabhu (The Companion Speak…) and Imran Ali Namazi (Power of Art). In their own way, each serves as an illustration of how artistic pursuit can becomes a means for one’s inner growth and transformation.

We hope our readers will enjoy going through the various offerings in this issue. As always, we offer this work at the lotus feet of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother.

In gratitude,

Beloo Mehra (for Renaissance Editorial Team)

Notes

- Here it may be added that one important difference between a ‘fine artist’ and a ‘folk artist’ has to do with how each has acquired the necessary skills to pursue their respective arts. While the former may have had a more formal learning in one or more specific art forms or media of expression, the latter generally picks up the skills informally in a communal space from his or her ancestors and passes on the knowledge to the young nearby. ↩︎

~ Design: Beloo Mehra