Volume V, Issue 11-12

Author: A.B. Purani

Editor’s Note: We feature excerpts from a lecture delivered by A. B. Purani at the J J. School of Art, Bombay (now Mumbai), on February 1, 1954. We have highlighted those sections in particular that speak of the art-creation processes. The focus is also on some of the distinctive aspects of artistic tradition in India.

We present the selections in 2 parts. For the ease of online reading, we have added a few appropriate headings. We have also made a few minor formatting changes without altering the text.

PART I

Introductory Inspiration: Learn and Then Forget the Technique

I have undertaken this task not because I want you to accept my ideas. But because I have a liking and respect for some of our young artists and art students. I admire their earnestness. And I want to be of some service to them in clarifying some of the fundamentals of art. I want to bring to their notice that besides European art there are other arts equally great. And that there is much to learn and assimilate in them.

I want to put before them some ideas of Sri Aurobindo on arts. These are ideas he gave to mankind in order that man may be able to fulfil his destiny, and live a divine life on earth. Let me tell you, students, that most of you lack mastery over technique—any technique—which gives discipline to the artist. The mastery which the Chinese and the Japanese artist has —and which the Indian and Italian artist had—over his technique is not found among modern artists.

It is true that technique is not all, and that mere technique is not art. But the discipline, the control of the material which the mastery of the technique gives is very precious. The effort to create without mastery over technique is like trying to write poetry without grammar or even language. The artist must learn and then forget the technique.

Respect the Tradition

Europe has dominated the world for more than two centuries not only in economics and politics but in literature and arts. This domination by European culture has produced a very tonic effect on many cultures in Asia and has given rise to renaissance in their literature and life generally. But together with much good this domination has also given rise to a general inferiority complex. And in the field of arts particularly this has resulted in lifeless imitation of European art and soulless attempts by Indian artists. Except the work done by Indian artists in the years when the national consciousness awoke.

The European critics told the world that India had no art. And Indians swallowed this nonsense for more than two generations. All arts except those that Europe had created were ‘primitive’. Greek art which is the parent of later European art was the standard by which all art had to be judged. All these uncritical ideas have to be given up. Fortunately, thoughtful men in Europe are giving them up.

It is good to remember that however unconventional the art of Europe may be for the last century, even European art had its tradition. Let us also remember that Persia, China,[1] Japan and India have had their arts—arts of long standing, and that their artistic value need not necessarily depend upon their fulfilling the standards set by the latest current fashion or theory or values current in Europe.

Express the Spirit in New Forms

It is true that our artistic activity—as all our cultural life—came to a standstill practically with the loss of freedom and cultural decline. During the period of domination England forced upon India European art-ideals, methods and values. Schools of art were compelled to teach only European art and by European methods.

It was only in Calcutta at the end of the last century that an English artist of exceptional calibre, Mr. E. B. Havell, introduced on his own responsibility Indian art, its ideals and methods in the school at Calcutta. It is not that European culture has done India no good. Far from it. Some great and eternal values like freedom, value of the individual, need of organising collective economic life for general progress—these are elements that are bound to lead men to progress.

… Let us shake ourselves free from this cultural domination. Let us not reject what we need and can assimilate. But let us not harbour the illusion that whatever the West thinks and does is perfect. Let us not blindly accept their values and judgements.

Let us take what we have to, and need. But also let us find out whether we have anything to give, to contribute. Let us not be servile imitators of a dead past, or living present of Europe. Let us free ourselves from the false notion that holding on to Indian technique—of whatever period or school—is the way to express the soul of India in art-forms.

[…]

Tradition as a Protecting Influence and Discipline

Art has to create forms, it is true. But has it not to create forms that express beauty, some self-existent harmony, some rhythm, which our intuitive faculty of appreciation can feel?… Forms for the sake of forms cannot hold the aesthetic sensibility for long. It is “beauty” “harmony”, and some inner quality of Truth—some power in the form that endows it with a Reality, that gives permanence to a form in art.

Most of the forms that are created under this subjective trend by modernist artists hardly embody these aspects. They excite one’s curiosity at the most, some of them tremble under the feet of the aesthetic sense. It is true that man must be prepared to change or develop his sense of appreciation of forms by accepting new forms—forms that have been created from within by the artist.

But the question is: Are they “forms”?[2] Secondly “forms” because they are ‘new’ have the right to be called “artistic”?

Tradition is a bondage if it dominates but it is also a protecting influence and disciplines the artist. When that protection is gone, there comes in the field of art unruly self-will, desire to be singular, even queer. And it leads ultimately to chaos. The artist comes to believe that what is new is necessarily great— a work of genius. He wants to be striking and extraordinary—there is straining for effect. As a result he tends to become obscure.

Subjectivism Gone Wrong?

When the modernist movement began in Europe, nobody could believe that the forms of art which the ultra-modern school has given us, would ever come out of it. The artists only wanted in the beginning of represent their “sensation” of the object.

This meant that he was feeling that he is not bound to represent the object as it was, i.e. to imitate Nature. The sensation meant the impression produced on his senses and interpreted by his mind. Then his “I” came to the front and wanted, or began, to take freedom with line, with colour. And ultimately he wanted to be independent of all bondage to Nature. His “Self”, he asserted, was free to express itself. He claimed the right to create forms that did not exist in physical nature, in life.

He accepted in the beginning the forms of nature as raw materials—as repertoire for his new creation. But he distorted, twisted and dislocated the forms of Nature in his new creation. The onlooker, instead of perceiving the delight of new creation, very often feels only the violence of the distortion on his sensibility. One may say that the aesthetic sense of the onlooker requires to be trained to appreciate this new creation.

Now, no one ever disputed, in the East at least, the right of the artist to create forms that have nothing in common with natural forms. But when it is asserted that the artist should not imitate Nature and when the artist begins to distort the forms of Nature, then the memory of the natural form constantly reminds the onlooker of the correspondence. And it is therefore difficult to feel it as a new creation.

Transform, Do Not Distort

What is needed is to “transform”, not merely to take liberty with and “distort” the forms of Nature in art. Otherwise, as Anand Coomarswamy says, the forms will only be “ denatured ”—contrary to Nature. This creates the impression of unnaturalness, violence, repulsion. This “transformation” of nature in art cannot be made by merely changing the outer, the external parts of the natural form. Such a change or transformation to be real and effective must be organic. This work of transformation has to be done by the inner being of the artist. Not by his outer mind, or by his intellectual theory about forms,[3] or his erratic unregulated fancy, or his subconscious.

So, while we do accept the right of the artist—as the ancients in the East and the West had done,—to create new forms, we find it difficult to accept as valid the methods he adopts for his creation.

I have said already that a form because it is “new”, —i.e. independent of Nature—is not therefore “artistic” or “beautiful” or aesthetically satisfactory. These forms too must satisfy the fundamental elements of beauty.

The method employed by modern artists is often without discipline,— chaotic. Sometimes it seems the artist is trying to exhaust the methods of distortion possible with a natural form—a human face or an object. Often the result is mutilation of Nature, it may lead to a sense of the strange and bizzare. It does not give joy which is the mark of true creation. If we are told that the artist feels delight in these creations, we may say, “Perhaps he does, if it is creation, it is not normal, not human but creation from lower subconscient world with its chaotic and amorphous forms”.

The Ancient Method of Inner Concentration

In this task of arriving at the correct technique of creating new forms, it may be of interest to consider whether there could be a synthesis of the technical advance attained by modern art in the West and methods of creating forms known in ancient India and countries of the far East. That may, perhaps, help us to find a way out of the present impasse.

The Indian method was that of inner concentration on the subject,—or one may even say, ‘on the object’. The artist has to allow the form that corresponds to the subject to arise out of his consciousness as a result of this concentration. […]

Often it may be an outer suggestion, excitement of some sense or some experience of life that may start the process and set the creative consciousness of the artist to work. What is created may bear some sign of the originating cause. But the form thus created corresponds to the subject of his concentration. This was what the ancients meant by “correspondence” or sadrsya. It is not outer resemblance or imitation of the natural form. But rather the correspondence of the form created with the consciousness of the artist, its being the true representation of that which the creator wants to express or create.[4]

The artist concentrates his consciousness (on the subject, or on the object) which attracts his will to create. This itself becomes a kind of discipline. And it rules out erratic suggestions, phantom forms, random fancies, eruptions of the subconscient, intrusion of the strange and such other things that are irrelevant to his artistic aim.

Some Examples from the Past

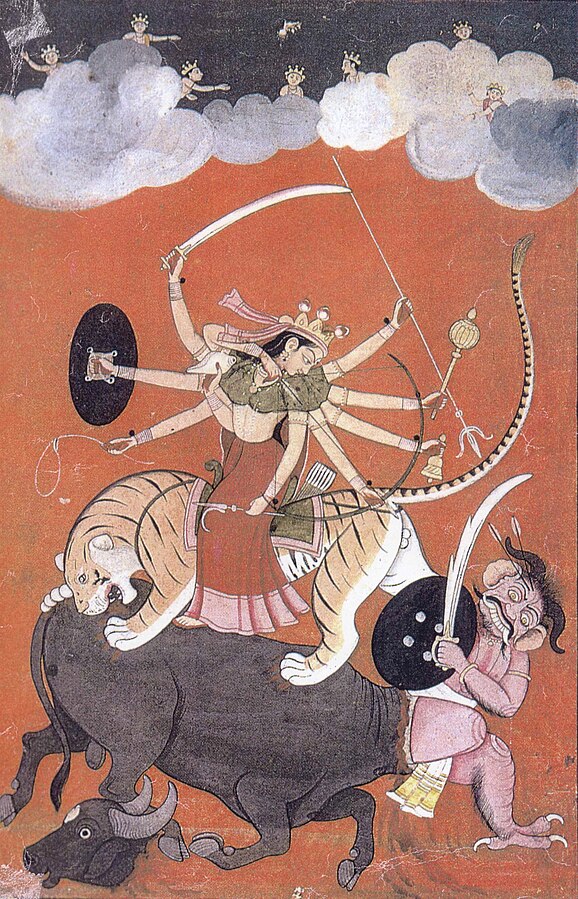

For illustrations of this method in art, one may look at the forms of God and Goddesses and those of the Titans—Asuras and Raksasas—that eastern art has created. They do not observe the rules of human anatomy— for, as Dr. Coomaraswamy said “they are not expected to function biologically”. But they do give us an impression of superhumanity which they are intended to represent.

It is possible that the aesthetic sense of an observer who has never thought of art-creation beyond Nature may find it difficult—if not impossible—to appreciate these forms. And it may even conclude, as once Joshua Reynolds did, that “this art is barbarous”.

But if it stops a little and allows the first reaction to subside, it may find that the form, though beyond nature, satisfies his sensibility and even his demand of beauty. One says, “yes, this kind of form is possible. It is even beautiful, has a beauty of its own—but not on our material plane”. The form has proportion, rhythm, which lends it a kind of beauty. Twelve or six hands of Goddess or God seem at first sight to break the rule of human anatomy. But it conveys the spiritual aspect or its own truth. And at the same time the disposition of the limbs appear to our intuitive sense quite proper—appropriate and even beautiful.

The elimination of wondering impulses, fancies and suggestions allows a kind of steady form to emerge or precipitate itself in the consciousness of the artist which has a reality of its own. Dr. Coomaraswamy in his book, Transformation of Nature in Art refers to Malvikagnimitra, a Sanskrit drama, in which there is reference to portrait painting. The reason for failure in making a portrait is said to be “shithila samadhi” or “lack of concentration or identification”—and not want of observation or imitation.

Notes

- “Chinese art has a consistent history and is even more persistent than the art of Egypt. It is more than national. Thirty centuries before Christ it began and yet Europe has not been able to enter into the spirit of this art. Its inward spirit still remains strange and remote ….. We are passive spectators of a way of thought and life which is beyond us. The East yields its secret slowly. And one may say that in order to appreciate these works of art to the full, one has to acquire new way of looking at the world. It may be said without exception that the oriental artist is never looking at the world from our point of view”. —Herbert Read, Meaning of Art.

- “All expression is not art”.— Herbert Read

- “It has always been recognised that the source of art’s appeal lies in these unconscious regions. A work of art cannot be constructed rationally”. —Herbert Read, The Meaning of Art.

- “Aryan and Semitic races have different modes of aesthetic expression. The Aryan sees in painting not a means of interpreting the outer world, but a means of expressing the inner self”. —Herbert Read, The Meaning of Art.