Volume VI, Issue 4

Author: Beloo Mehra

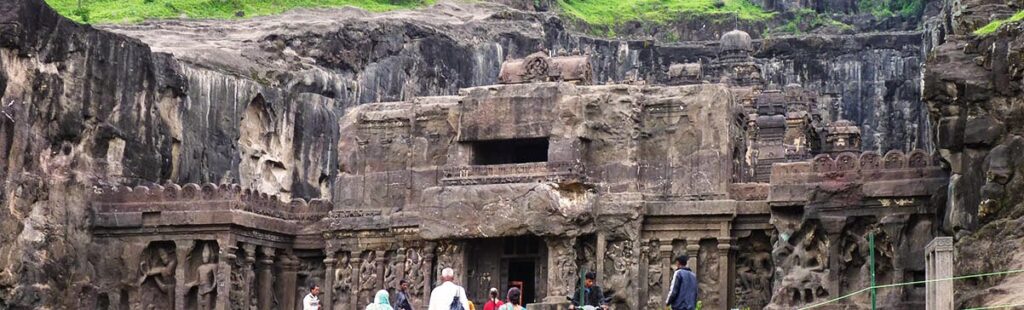

Editor’s Note: India’s long and rich sculptural tradition is closely connected with her temple architectural tradition, known together as vaastu parampara. The intimate connection between these two art forms is exemplified perfectly by Kailasha Temple at Ellora caves. The following is the author’s experiential account of her visit to Kailasha temple and other caves of Ellora.

The Historical Overview

The cave-temples at Ellora, Maharashra were excavated in three broad periods: an early period from around 550 to 600 CE when most of the cave-temples dedicated to Hindu deities were built; the period from about 600 to 730 CE when most of the caves dedicated to Buddhist deities were built; and a later phase from about 730 to 950 CE when again Hindu and Jain cave-temples were built.

Cave number 16 or the Kailasha temple is the largest of the 34 cave temples and monasteries in the complex. It is one of the most remarkable cave temples in the world. Most of this temple was built during the reign of the eighth century Rashtrakuta king Krishna I (756–773 CE), though some parts were completed later. Considered as the climax of the rock-cut phase of Indian architecture, this temple is unique not only because of its size, architecture and sculptures, but it is most notable for its vertical excavation method, which means that its carving started at the top of the original rock and moved downward.

The Temple Story

There is an interesting Marathi legend about the Kailasha temple, mentioned in a text called Katha-Kalapataru. Once when a local king was suffering from a severe disease, his queen, an ardent devotee of Ghrishneshwara, a form of Lord Shiva, vowed that she would construct a grand temple for the Lord if her husband was cured. Not only that, she also vowed to observe a fast until she could see the shikhara of this temple.

The Lord heard the queen’s sincere prayers. When the king was cured, she wanted to build a temple as soon as possible. Several architects were interviewed, but they all said that it could take many months to build a temple complete with a shikhara. This would mean a long time of fasting for the queen.

But then came along an architect named Kokasa who assured the royal couple that the queen would be able to see the temple shikhara within a week. It sounded almost unbelievable, but Kokasa convinced the royal couple and the work began. Kokasa executed his plan to build the temple from the top, and thousands of workers started carving a massive rock bit by bit. The shikhara was completed within a week’s time. And on seeing that the queen concluded her fast in a spirit of gratitude to the Lord.

Scholars and art historians today agree that Kokasa was indeed the chief architect of the Kailasha temple. In fact, several inscriptions found in various parts of India mention Kokasa and several other architects from his family lineage.

The entire monolithic cave-temple, carved from top to bottom, was planned at the beginning. No major part of this architectural marvel appears to have been an afterthought. The main shrine bears similarity to the Virupaksha Temple at Pattadakal, built by Chalukyas of Badami, which itself is closely inspired by the Kailashanatha temple built by Pallavas at Kanchi. Such continuity of temple architectural styles with regional experimentations and variations is a remarkable aspect of Indian architectural tradition.

The Sculpture Story

Walking through the two-storey cave temple, one is constantly in a state of awe as the eyes take in numerous free-standing and relief sculptures that are just as grand as its overall architecture. There are gods and goddesses representing Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shakta traditions, as well as several panels depicting stories from the Rāmāyana and Mahābhārata.

In cave number 16, a massive sculpture, expressing a great synthesis of dynamism and stillness carved in stone, is bound to mesmerise anyone. This magnificent work of art tells the story of Ravana lifting Mount Kailash, the mountain abode of Lord Shiva and Ma Parvati. This story appears in the Uttara Kānda of the Rāmāyana.

The story goes that Ravana, after defeating and looting the city of his step-brother, Kubera, had become excessively arrogant and conceited. Returning in his flying chariot — Pushpak vimana, which he had stolen from Kubera — he came across a mountain over which the chariot was not able to fly. He saw Nandi, the eternal attendant of Lord Shiva, guarding the place and asked why he could not pass. Nandi informed him that his Lord Shiva and Devi Parvati were resting on the mountain, so nobody could disturb them at this time.

Deluded in his arrogance, Ravana not only ridiculed Nandi but also insulted his Lord Shiva, which of course Nandi would never tolerate. He cursed Ravana that a band of monkeys would destroy his arrogant pride. Enraged at this, Ravana decided to show his strength. Uprooting the Kailash mountain, he lifted it up onto his head. As the mountain shook, Shiva realised what was going on and with his toe simply pressed the mountain down.

Trapped below the colossal mountain, the mighty Ravana cried out in intense pain. Realising the power of the omnipotent Lord Shiva, he now started praying to the Lord for forgiveness and compassion. It is said that while remaining trapped in this position, Ravana sang the glories of Lord Shiva for a thousand years, after which he was forgiven.

The mūrti at Kailasha temple has made this story come alive in stone. The same story is also depicted in cave number 29 at Ellora.

My Indian Story

Experiencing the rasa when spending time with such mesmerising works of art, and taking in the deep symbolism of the stories being depicted through such sculptures, one is bound to recognise that India is truly a living being and not merely an intellectual ‘idea’ as many fashionable intellectuals claim. Perhaps India cannot be truly known by an analytical study of her ideas; maybe we can come closer to the truth of her life-force only if we listen closely to her stories, stories in which her highest ideas and ideals have taken the form of lived and living truths. To know India, know the stories of India — with this thought I tell my story.

I was going through some pictures from my trip to Ellora Caves from 13 years ago. A little story started to take shape. A story of discovery. Of finding a path, of seeking for a way, of unearthing of a road. Road to another discovery, another search, another seeking.

All outer journeys are indeed journeys taken on the inside. Or can be. Or should be.

The title ‘Unearthing the Path’ came. It also seems inspired by the way the Kailasha temple at Ellora Caves was carved — from inside out. Sort of like the path we must travel if we want to truly be ourselves, starting from within.

As the story continued to take shape, a story within the story was also born. Of another journey. Let the pictures now tell of such journeys.

Want to know where to begin? Enter the cave.

Don’t let the passageway be the end. Continue.

Trust that you are protected by higher forces.

If you must pause, pause to take in the grandeur and beauty of the road unearthed by those before you.

Be mindful of others walking their own paths, alone but nearby.

Do not be discouraged by the hurdles on the path to the inner chamber.

The Diamond in the Cave

For a long time she simply stood there, outside the cave, unsure of herself, weak in mind and heart, going over and over in her little head — should I enter this cave, or should I go back and forget all about this, what should I do, who can guide me? What will I find there if I enter, will it all be dark and gloomy and scary, will there be some deeply hidden secret stuff that I would rather not discover, will I be able to accept whatever it is I find inside the cave?

What if I am stuck there and can’t find my way out of that darkness? Who will I call upon for help to rescue me, who can I rely upon, who, who, who?

****

After what seemed to her ages, she felt she heard a very soft, almost-inaudible voice, a voice which seemed to be coming from nowhere, or perhaps from somewhere within her, a voice that seemed to be saying – “how else will you find the diamond if you don’t enter the cave?”

As if this was the cue she had been waiting for all this time… she not only found the courage to start the journey into what at first sight appeared to be a dark cave, but as she continued to go deeper and deeper and deeper, that same sweet voice coming from somewhere deep inside her also became her constant companion and the Guiding Light, assuring her that one day she will find the shining diamond, within.

If you find a guide, let it be someone who sets you free to chart your own path.

Be grateful for the little glimpses of beauty and truth along the way.

Keep walking, keep walking.

Value the details, but don’t get lost in them.

Feeling a bit lost? Get re-acquainted with the path.

As many times as it takes. Start again.

See your old footprints? Take their help.

Or make new. Keep walking.

Art and Life

The inner journey that this experience of Art made possible for me affirms clearly what Indian aesthetic and artistic tradition has always emphasised. Art is not to be seen as a mere pastime or a useless activity enjoyed for its own sake; rather art must be integral to and deeply connected with and rooted in life. High usefulness of art – both for individual human development and a harmonious collective life – has always been recognised.

Art can take one to new subjective understanding of oneself and the world around. Art has the potential to educate and elevate; it can open new vistas of perception and refine the innerscape of both the artist and the rasika. How is that possible? Sri Aurobindo explains:

Art is not only technique or form of Beauty, not only the discovery or the expression of Beauty,—it is a self-expression of Consciousness under the conditions of aesthetic vision and a perfect execution. Or to put it otherwise there are not only aesthetic values but life-values, mind-values, soul-values, that enter into Art. The artist puts out into form not only the powers of his own consciousness but the powers of the Consciousness that has made the worlds and their objects.

The artists who were behind the marvels such as Ellora caves, or Kailasha temple in particular, were able to integrate a hierarchy of life-values, mind-values, soul-values into their art. And depending on one’s level of consciousness, the rasika receives from the experience that for which one is ready. What is your story, o reader?

Watch this short video on cave temples of India

~ All pictures where the source is not mentioned are from the author’s private collection.

~ Design: Beloo Mehra