Volume II, Issue 6

Author: Nolini Kanta Gupta

Editor’s Note: We find here deeper meaning of spiritual call, initiation, adhikāra and the importance of endurance and steadfastness in the path of the Integral Yoga.

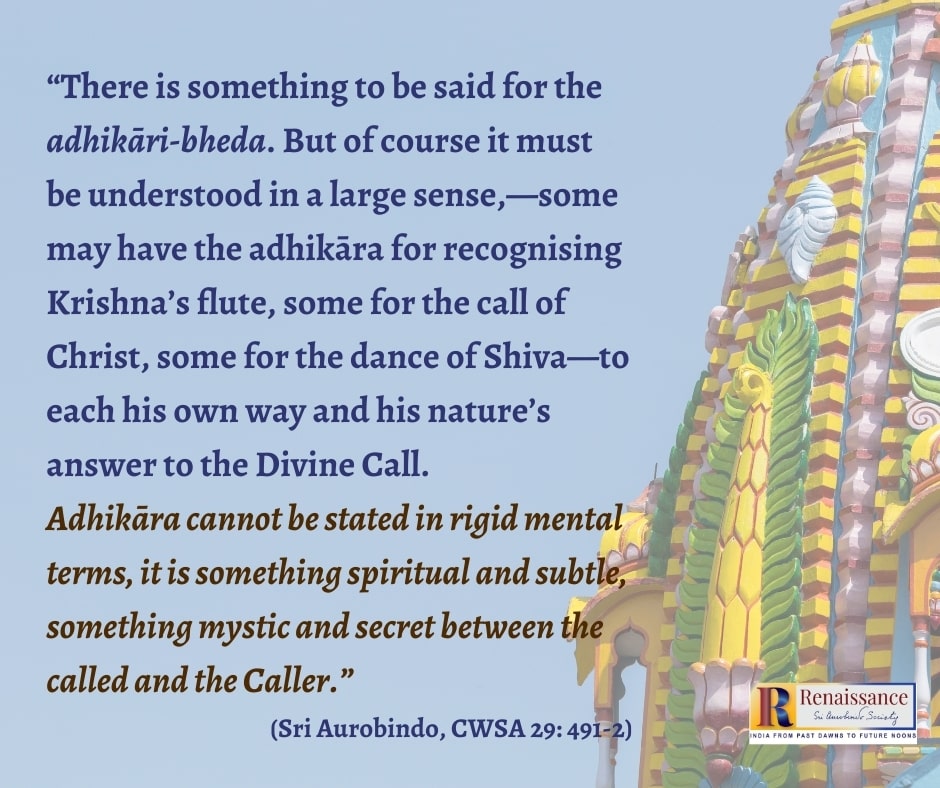

In the practice of Yoga a condition precedent is usually laid down: it is called adhikāra, aptitude, fitness or capacity. Everybody does not possess this aptitude, it is urged, and; cannot take to a life of Yoga at one’s sweet will.

There must be a preparation, certain rules and regulations must be observed, some discipline must be followed and one must acquire certain qualities or qualifications, must reach a particular stage and degree, rise to a particular level of life and consciousness before one can successfully face the spiritual problem.

It is not everyone that has a laisser-passer, a free pass to enter the city or citadel of the spirit.

The Upanishad gives the warning in most emphatic terms:

“This Atman is not to be gained by the weakling.” (Mundaka, III. 2. 4)

and again it declared:

“Nor to the fickle and the unsteady should this knowledge be given.” (Swetaswatara, VI. 21)

and yet again:

“Nor can one attain the Spirit by discussion and disputation, nor by a varied learning nor even by the power of intelligence.” (Katha, I. 2. 23)

Shankara, at the very outset of his commentary on the Sutras, in explaining the very first words, speaks of a fourfold sadhana to acquire fitness—fitness, we may take it, for understanding the Sutras and the commentary and naturally for attaining the Brahman. It seems therefore to be an absolute condition that one must first acquire fitness, develop the right and adequate capacity before one should think of spiritual initiation.

The question, however, can be raised—the moderns do raise it and naturally in the present age of science and universal education—why should not all men equally have the right to spiritual sadhana?

If spirituality is the highest truth for man, his greatest good, his supreme ideal, then to deny it to anyone on the ground, for example, of his not being of the right caste, class, creed, or sex, to keep anyone at a distance on such or similar grounds is unreasonable, unjust, reprehensible.

These notions, however, are born of a sentimental or idealistic or charitable disposition, but unfortunately, they do not stand the impact of the realities of life. If you simply claim a thing or even if you possess a lawful right to a worthy object, you do not acquire thereby the capacity to enjoy it. Were it so, there would be no such thing as malassimilation.

Fitness of the Aspirant

In the domain of spiritual sadhana there are any number of cases of defective metabolism. Those that have fallen, strayed from the Path, become deranged or even have had to leave the body, make up a casualty list that is not small. They were misfits, they came by their fate, because they encroached upon a thing they were not actually entitled to, they were dragged into a secret, a mystery to which their being was insensible.

In a general way we may perhaps say, without gross error, that every man has the right to become a poet, a scientist or a politician. But when the question rises in respect of a particular person, then it has to be seen whether that person has a natural ability, an inherent tendency or aptitude for the special training so necessary for the end in view. One cannot, at will, develop into a poet by sheer effort or culture. He alone can be a poet who is to the manner born.

The same is true also of the spiritual life. But in this case, there is something more to take into account.

If you enter the spiritual path, often, whether you will or not, you come in touch with hidden powers, supra-sensible forces, beings of other worlds and you do not know how to deal with them.

You raise ghosts and spirits, demons and gods—Frankenstein monsters that are easily called up but not so easily laid. You break down under their impact, unless your adhārā has already been prepared, purified and strengthened.

Now, in secular matters, when, for example, you have the ambition to be a poet, you can try and fail, fail with impunity. But if you undertake the spiritual life and fail, then you lose both here and hereafter. That is why the Vedic Rishis used to say that the earthen vessel meant to hold the Soma must be properly baked and made perfectly sound.

It was for this reason again that among the ancients, in all climes and in all disciplines, definite rules and regulations were laid down to test the aptitude or fitness of an aspirant. These tests were of different kinds, varying according to the age, the country and the Path followed—from the capacity for gross physical labour to that for subtle perception.

Test of Endurance and Obedience

A familiar instance of such a test is found in the story of the aspirant who was asked again and again, for years together, by his Teacher to go and graze cows. A modern mind stares at the irrelevancy of the procedure; for what on earth, he would question, has spiritual sadhana to do with cow-grazing?

In defence we need not go into any esoteric significance, but simply suggest that this was perhaps a test for obedience and endurance. These two are fundamental and indispensable conditions in sadhana; without them there is no spiritual practice, one cannot advance a step.

It is absolutely necessary that one should carry out the directions of the Guru without question or complaint, with full happiness and alacrity: even if there comes no immediate gain one must continue with the same zeal, not giving way to impatience or depression.

In ancient Egypt among certain religious orders there was another kind of test. The aspirant was kept confined in a solitary room, sitting in front of a design or diagram, a mystic symbol (cakra) drawn on the wall. He had to concentrate and meditate on that figure hour after hour, day after day till he could discover its meaning. If he failed he was declared unfit.

Needless to say that these tests and ordeals are mere externals; at any rate, they have no place in our sadhana. Such or similar virtues many people possess or may possess, but that is no indication that they have an opening to the true spiritual life, to the life divine that we seek.

Just as accomplishments on the mental plane, — keen intellect, wide studies, profound scholarship even in the scriptures do not entitle a man to the possession of the spirit, even so capacities on the vital plane, — mere self-control, patience and forbearance or endurance and perseverance do not create a claim to spiritual realisation, let alone physical austerities.

In conformity with the Upanishadic standard, one may not be an unworthy son or an unworthy disciple, one may be strong, courageous, patient, calm, self-possessed, one may even be a consummate master of the senses and be endowed with other great virtues. Yet all this is no assurance of one’s success in spiritual sadhana. Even one may be, after Shankara, a mumuksu, that is to say, have an ardent yearning for liberation. Still it is doubtful if that alone can give him liberation into the divine life.

Call, the One Indispensable and Unfailing Requisite

What then is the indispensable and unfailing requisite? What is it that gives you the right of entrance into the divine life? What is the element, the factor in you that acts as the “open sesame”, as a magic solvent?

Only one thing, represented by one small homely word — “Call”.

Whatever may be the case with other paths of sadhana, for Sri Aurobindo’s Path this is the keynote.

Has the call come to you, have you received the call? That is everything. If you have this call it does not matter in the least whether you have other qualities, be they good, be they bad. That serves as proof and pointer that you are meant for this Path.

If you have this one thing needful you have everything, and if you have it not, you have nothing, absolutely nothing. You may be wise beyond measure, your virtues and austerities may be incalculable, yet if you lack this, you lack the fitness for Sri Aurobindo’s Yoga.

On the other hand, if you have no virtues worth the name, if you are uneducated or ill-educated, if you are weak and miserable, if your nature is full of flaws and lapses, yet if the call is there in you secreted somewhere, then all else will come to you, will be called in as it were inevitably: riches and strengths will grow and develop in you, you will transcend all obstacles and dangers, all your wants will be made good, all your wear and tear will be whole. In the words of the Upanishad:

“Sin will not be able to traverse you, you will traverse all sin, sin will not burn you, you will burn it away.”

(Brihadaranyaka, IV. 4. 23)

Whose is this Call, from Where does it Come?

Now what exactly is this wonderful thing? This power that brings into being the non-being, realises the impossible? Whose is this Call, from where does it come?

It is none other than the call of your own inmost being, of your secret self. It is the categorical imperative of the Divine seated within your heart.

Indeed, the first dawning of the spiritual life means the coming forward, the unveiling of this inner being. The ignorant and animal life of man persists so long as the inner being remains in the background, away from the dynamic life, so long as man is subject to the needs and impulses of his mind and life and body.

True, through the demands and urges of this lower complex, it is always the inner being that gains and has its dictates carried out and is always the secret lord and enjoyer; but that is an indirect effect and it is a phenomenon that takes place behind the veil. The evolution, in other words, of the inner or psychic being proceeds through many and diverse experiences—mental, vital and physical. Its consciousness, on the one hand, grows, that is, enlarges itself, becomes wider and wider, from what was infinitesimal it moves towards infinity, and on the other, strengthens, intensifies itself, comes up from behind and takes its stand in front visibly and dynamically.

Man’s true individual being starts on its career of evolution as a tiny focus of consciousness totally submerged under the huge surface surge of mind and life and body consciousness.

It stores up in itself and assimilates the essence of the various experiences that the mind and life and body bring to it in its unending series of incarnations; as it enriches itself thus, it increases in substance and potency, even like fire that feeds upon fuels.

A time comes when the pressure of the developed inner being upon the mind and life and body becomes so great that they begin to lose their aboriginal and unregenerate freedom—the freedom of doing as they like; they have now to pause in their unreflecting career, turn round, as it were, and imbibe and acquire the habit of listening to the deeper, the inner voice, and obey the direction, the command of the Call. This is the “Word inviolate” (anāhata-vānī) of which the sages speak; this is also referred to as the “still small voice”, for indeed it is scarcely audible at present amidst the din and clamour of the wild surges of the body and life and mind consciousness.

Now, when this call comes clear and distinct, there is no other way for the man than to cut off the old moorings and jump into the shoreless unknown. It is the categorical demand of such an overwhelming experience that made the Indian aspirant declare:

“The moment you feel you are not of the world, loiter no longer in it.”

It is the same experience that throbs in the Christ’s utterance:

“Follow me, let the dead bury their dead.”

The inner soul—the psychic—very often undergoes a secret preparation, develops and comes forward but just waits, as it were, behind the thin though opaque screen; and because of that it gives no objective indication of its growth and readiness. We see no patent sign of what is usually known as fitness or aptitude or capacity. Otherwise how to explain the conversion of a profligate and dilettante like Augustine, or of a rebel like Paul, or of scamps like Jagai-Madhai.

Often the purest gold hides in the basest ore, the diamond is coal turned, as it were, inside out. This, one would say, is the Divine Grace that blows where it lists—makes of the dumb a prattler, of the lame a mountain-climber.

The Action of Divine Grace

But what is this Divine Grace and how does it move and act?

It does not act on all and sundry, it does not act on all equally. What is the reason? Appearances often belie the reality: a contrary mask is put on, it would appear, deliberately, with a set purpose. The sense and significance of this mystery? The hard, obscure, obstinate, rebel outer crust may continue long but it is corroded from within and one day, all on a sudden, it crumbles and dissolves and becomes in a new avatar the vehicle and receptacle of the very thing it opposed and denied.

Virtues are not indications of the fire of the inner soul, nor are vices irremediable obstacles to its growth.

The inner soul, we have said, feeds upon all—it is indeed fire, the omnivorous, sarvabhuk, —virtues and vices and everything else and gather strength from everywhere. The mystery of miracles, of a sudden change or reversal or revolution in consciousness and way of life lies in the omnipotency of the psychic being.

The psychic being has the power of making the apparently impossible, for this reason that it is a portion of the almighty Divine, it is the supreme Conscious-Power crystallised and canalised in a centre for the sake of manifestation. It is a particle from the Being, a spark of the Consciousness, a ripple from the Delight cast into the fastnesses of Matter and the, material body.

Now, it is the irresistible urge of this particle, this spark, this ripple to grow and expand, to become in the end the Vast—the Ocean and the Sun and the sphere of Infinity—to become that not merely in an essential status but in a dynamic and apparent becoming also.

The little soul, originally no bigger than a thumb, goes forward through one life after another enlarging and intensifying itself till it recovers and establishes its parent reality in this material body here below, till it unveils what is latent within itself, what is its own, what is itself, — its integral self-fulfilment, the Divine integrality.

Here in his inner being, as part and parcel of the Divine, man is absolutely free, has infinite capacity and unbounded aptitude; for here he is master, not slave of Nature, and it is slavery to Nature, that limits and baulks and stultifies man. So does the Upanishad declare in a magnificent and supreme utterance:

“It is he in whom the soul, sunk in the impenetrable cavern of the body, darkened by dualities, has awakened and become vigilant, he it is who is the master of the universe and the master of all, yea, his is this world, he is this world.”

(Brihadaranyaka, IV. 4. 13)

In the practice of Yoga the fitness or capacity that the inner being thus lends is the only real capacity that a sadhaka possesses; and the natural, spontaneous, self-sufficing initiation deriving from the inner being is the only initiation that is valid and fruitful. Initiation does not mean necessarily an external rite or ceremony, a mantra, an auspicious day or moment: all these things are useless and irrelevant once we take our stand on the authentic self-competence of the soul.

The moment the inner being has taken the decision that this time, in this life, in this very body, it will manifest itself, take possession of the body and life and mind and wait no more, at that moment itself all mantra has been uttered and all initiation taken. The disciple has made the final and definitive offering of his heart to his Guru—the psychic Guru—and sought refuge in him and the Guru too has definitely accepted him.

Mantra or initiation, in its essence, is nothing else than contacting the inner being.

In our Path, at least, there is no other rite or rule, injunction or ceremony. The only thing needed is to awake to the consciousness of the psychic being, to hear its call—to live and move and act every moment of our life under the eye of this indwelling Guide, in accordance with its direction and impulsion.

Our initiation is not therefore a one-time affair only; but at every moment, at each step, it has to be taken again and again, it must be renewed, revitalised, furthered and strengthened constantly and unceasingly; for it means that at each step and at every moment we have to maintain the contact of our external consciousness with the inner being; at each step and every moment we have to undergo the test of our sincerity and loyalty—the test whether we are tending to our inner being, moving in its stream or, on the contrary, walking the way of our external animal nature, whether the movements in the mind and life and body are controlled by their habitual inferior nature or are open to and unified with their hidden divine source.

This recurrent and continuous initiation is at the secret basis of all spiritual discipline—in the Integral Yoga this is the one and all-important principle.

(Collected Works of Nolini Kanta Gupta, Vol. 3, pp. 68-75)

~ Design: Beloo Mehra