Volume II, Issue 3

Author: Dr. Rajeshwari

Continued from Part 2

Editor’s note: Dear readers, here is the story that Rajeshwari promised in the last part. . .

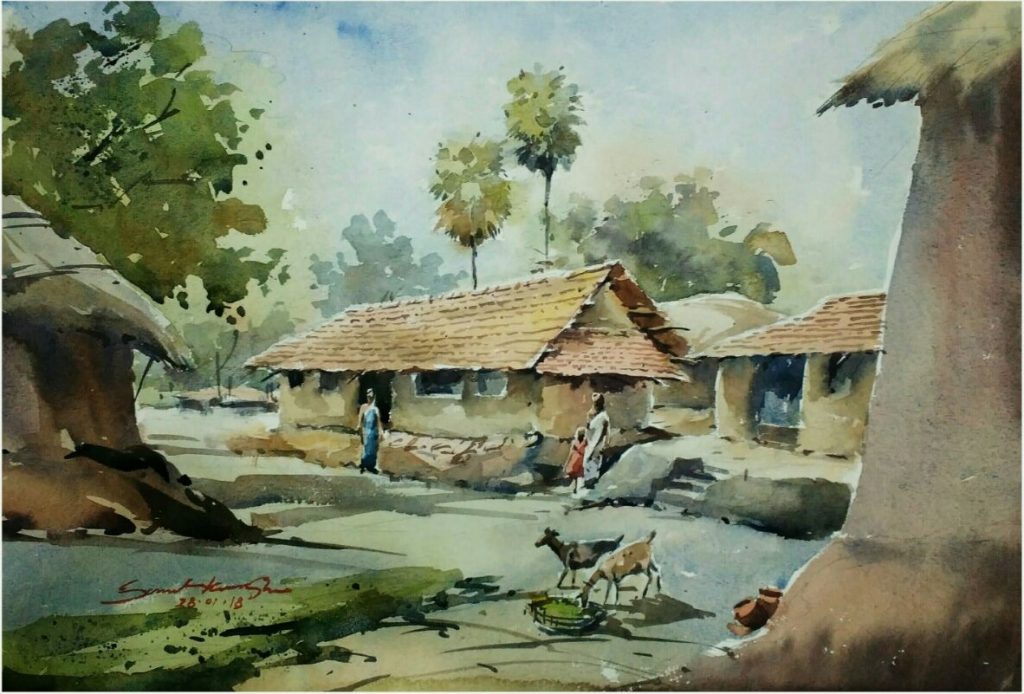

In that remote village of South India a long time ago, lived the venerable Elder of over a 100 years. Simply known as Thatha (grandpa), he was a repository of ancient folk wisdom he had learnt from his forefathers. He had a panacea for every physical and mental illness about which the villagers consulted him. He gave them simple remedies and solutions.

Among the many things he had learnt was that one should not walk or sleep under a tamarind tree at night. In order to keep the villagers from going into the tamarind grove at night, he told them that there were ketta kaatru (noxious gases – another name for ghosts in Tamil) there. His word was accepted by everyone, except a group of sceptical youth, who thought that he was superstitious.

So, one night, the friends decided to go to the grove and sleep there, to challenge the advice given by Thatha. They lay under a big tamarind tree, telling jokes, laughing and chatting about ghosts and spirits. Hardly had they slept, exhausted, when they awoke one by one, in cold sweat and unable to breathe. The terrified boys were convinced that they had been ‘caught’ by the ghost! Leaving their mats and pillows, they somehow managed to run back to their homes in the village, screaming their heads off.

Next morning, the boys woke up with severe body ache and palpitations and lost no time to seek out the Elder. In anxious tones, they told him that something had indeed ‘caught’ them at night, but were surprised to see him simply standing there, smiling. ‘So you met the ghost!’ Thatha chuckled. The boys looked suitably chastised. He then gave them a simple prescription of walking on a road lined with tamarind trees during the day and sleeping under a big neem tree at night, for the next 40 days.

The boys were now afraid of going anywhere near a tamarind tree, even during the day, leave alone sleeping under any tree after their previous night’s scare. Finally, Thatha accompanied them. Surprisingly, their aches and pains vanished and palpitations were gone, when they woke the next morning. Naturally they were curious to know how they had been cured and wanted to know why they should continue the treatment for 40 days.

Thatha then told the boys that for some time after having inhaled toxic air through their mouth, the experience and its memory might scare them again while talking and sleeping – just the way it had the first time, especially if they were alone. The prescribed treatment for the 40-day period would ward off this situation.

He also explained that certain trees including the tamarind tree, and a tree with similar fruits/pods like tamarind which grows extensively around the country, variously called Kodukkapuli/Vilayati imli/Madras thorn (Botanical name: Pithecellobium dulce) give out prāña vāyu like the other trees during the day, but breathe out all the ketta kaatru (noxious gases) at night. The boys had felt choked that night because they had been chatting non-stop before going to sleep, and then inhaled so much of carbon-dioxide during their sleep. On the other hand, because the neem tree releases prāña vāyu all through the day and night, they had felt refreshed in the morning after even a single day of treatment.

Thatha hastened to add that even when the tamarind tree and others of its kind breathed out all the noxious gases at night, they were in fact readying themselves to give out prāña vāyu the next morning to continue helping humans and animals. This explains how these trees help when they can but are helpless when they cannot. In this way, the plant kingdom teaches us a lesson about helping fellow beings whenever we can without shirking away the responsibility of doing so.

Why only 40 days, and why not more or lesser number of days? There was a spiritual reason in addition to a physical one for this, Thatha told the boys who by now had become curious and open to understanding more.

Panćabhūta and Panćēndriyā

Let you and I also follow Thatha and understand the reason behind 40 days of treatment. For this, we first need to about the term vratam. Sanyāsis and mathādiśas of ascetic orders observe Chaturmāsya vratam, starting from the month of Jyēśtha (ज्येष्ठ). During this period, they go to secluded places for four months, where there is no disturbance or sensory distraction in the form of visitors. They live on a frugal diet of fruits and uncooked food, eating just once a day. This is a sātvik way of observing vratam giving the necessary rest to the panćabhūtas in the body and panćēndriyas of the mind. Our elders have stipulated this period of vratam during the monsoons, when our body and mind need the deserved rest.

For the bodily organs are governed by the panćabhūtas, any course of treatment is a kind of vratam. For example, one organ in the body—say, the respiratory organ—may accept the new habit of walking through the grove of tamarind trees in the morning and through the grove of neem trees in the evening. But other organs—for example, digestive organs—may not accept this ritual right away. It normally takes 40 days for all organs to function in sync, to achieve complete cure as per the organ clock theory.

This is same as the idea that practice makes one perfect. For instance, many months of practice are necessary for an athlete before he or she can enter a competition. Similarly, the period of time for all organs to get accustomed to a particular pattern of behaviour is 40 days. When combined with a regular pattern of dietary intake this is the right way to ensure proper healing and good health.

The panćabhūtas have a very close relationship with panćēndriyas (five sensory organs). These, namely śabdam, ruchi, gandham, drşti, and sparśam (sound, taste, smell, sight and touch) create powerful hurdles in our effort to practice sādhanā vratam and dhyāna. Though our body may sit still at one place, our mind wanders all over the globe; our ears may be sensitive to the slightest distraction; our hand instantly rises to scratch the skin if a mosquito bites us; our eyes will open to see what caused the specific smell, and so on.

No wonder Adi Shankaracharya referred to the panćēndriyas as wild animals. In the 43rd shloka of Śivānandalahari, he says:

मा गच्छ त्वमितस्ततो गिरिश भो मय्येव वासं कुरु

स्वामिन्नादिकिरात मामकमनः कान्तारसीमान्तरे

वर्तन्ते बहुशो मदजुषो मास्तर्य मोहादय

स्तान् हत्वा मृगयाविनोदरुचितालाभं च संप्राप्यसि II

Don’t go here and there, O God of the mountains,

And please my Lord, always live in me.

For O primeval hunter, within the limits

Of the dreary forest of my mind,

Live many wild animals like envy, delusion and others,

And you can kill and do thine sport of hunting,

And enjoy there yourself.

That is the literal meaning of the verse. Here is another one that is closer to my heart.

O! Śiva! You came to give Paśupathāstra to Arjuna. You are the first and foremost hunter. If you are fond of hunting, you need not go anywhere else. Come and stay in my hrdayam (heart) and hunt the most dangerous wild animals that dwell there, as you please, and give me your anugraha (grace).

If Śiva were to dwell in our hearts, His anugraha will be perfect and permanent, as he will hunt the itinerant índriyas and kill them or keep them under his control and prevent their wandering.

It is interesting to learn how the inter-connection of the panćēndriyas and, in turn, their connection with the panćabhūtas, bind the jīvātmā with the Paramātma – held by the prāña till we leave our mortal body – and then directly binding with Him when prāña link is severed.

More about that in future parts of the series.