Volume II, Issue 6

Author: Dr. Rajeshwari

Continued from Part 5

The moment an ancient custom or tradition is mentioned, often the first question that is raised is if there is any scientific basis to this practice or is it just a superstition. Scepticism demands concrete proof. This ongoing series on physical and spiritual wellness as practised by ancient Indians specifically addresses this issue.

Read previous PART for Sri Aurobindo’s explanation of superstition

My attempt in this series has been to unravel the astonishing scientific wisdom of our ancestors, which has been handed down the generations in an unbroken chain. They achieved perfect health by harnessing the power of the Five Elements or panchamahābhuta-s for their benefit, even while nurturing them in return, thus living in harmony with the Universe. Even in the 21st century, we have wise elders who continue with these ancient practices, helping those around them.

How Vāyu both Helps and Hinders Śabdam

We saw in the previous part how śabdam aids vāyu in the body by helping to eliminate the toxic gases that get accumulated in the lungs and tissues, through yawning and sneezing. The help is however, not one-sided, because sound also needs a bhūta to travel – either vāyu (air) or āpah (water).

This is the reason why space is silent, as it is a vast vacuum. Any sound is heard only when the object (meteorite, spacecraft or any space debris) strikes the atmospheric layer, where there is air to carry the sound.

Just as in the external universe, in the micro-universe of our body the bhūta that is vāyu and the índriya that is ear help us receive and produce sounds, including speech and music. The vocal cords play the major role in this in-built programme created by Nature.

And yet, the same vāyu which helps śabdam in so many ways can at times be its foe and a hindrance too. We have all come across the following commonplace sights that seem rather quirky but are some of the best illustrations of folk wisdom which uses the above scientific fact to deal with everyday problems connected with sound.

- Street vendors shouting at the top of their voice with a hand covering one of their ears – usually the right.

- Cupping the hands around the mouth when calling someone who is at a distance. (Note that the ear is not covered here).

- A singer covering one of his/her ears with the hand while singing in the upper octaves.

- Since infants cannot cover the ears, they are not allowed to cry for a long duration by elders in the family. There are exceptions to this rule too, but we will come to that later.

Before analysing the reasons for the above examples, we should understand the structure and functions of the voice box (larynx) which is situated at the top of the trachea or windpipe, leading to the lungs.

The Voice Box

If we peek down a wide-open mouth, we can see the voice box at the base of the throat. Its structure is like that of an inverted harp, the musical string instrument. Here the ‘strings’ are the vocal cords.

While we need to strum the strings of the harp with our fingers to produce music, the unique harp in our throat produces sounds in all octaves just with the aid of vāyu. In other words, we can say that it functions more like a windchime that produces notes in various octaves when the wind passes through it. The prāña bellowed out from the lungs through the mouth vibrates and modulates these harp-like cords, to produce a variety of sounds in all pitches, including speech and music. It is pertinent to mention here that the infant’s cry is shrill because these cords are very fine and delicate and still undeveloped.

The deep inhalation and exhalation during prāñayama bring out the prāña through the nostrils. But when we open our mouth to speak, shout or sing, the sound pushes the air through the vocal cords to make the voice heard.

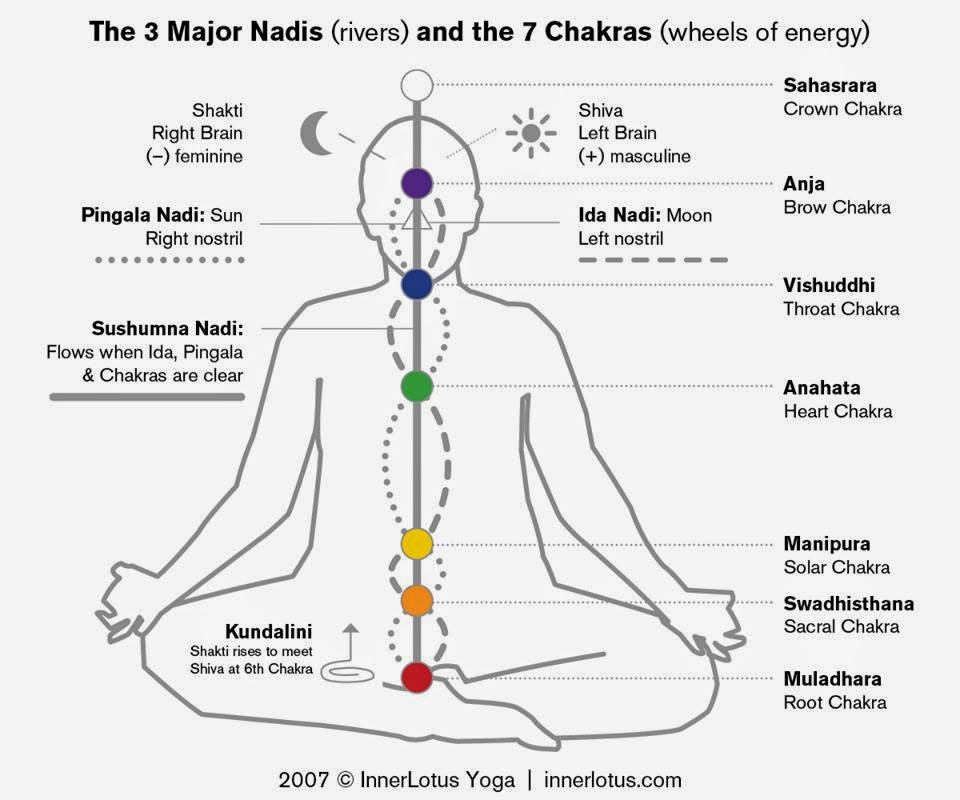

These vocal cords have a distinct role in producing music. The great 18th century poet and saint Thyagaraja has brought this out beautifully in one of his kritis, called śōbhillu saptaswara. The lyrics – नाभि, हृद्, कण्ठ, रसन, नासादुलयन्दु. . . illustrate the saptaswara’s divine beauty rising step-by-step from the nābhi (navel), hṛdya (heart), kanṭha (throat), rasana (tongue) and finally nāsā (nostrils). Only a well-trained singer who can connect himself with the paramātmā through each of the chakras can produce such an effect in the saptasvaras.

Vocalists do riyaz long before sunrise, during Brahmamuhūrtam, when there is abundant oxygen in the air. The air that enters the mouth is unpolluted, making the task of the voice (sound) easier.

What about the Ear?

If it is the prāña from our lungs passing through the various chakras that produces sound, what does the ear have to do with it? Why does one cover the ear while singing or shouting, or while raising one’s voice to be heard above the din, and why at other times it is not necessary? The answers to these questions lie in the fact that vāyu not only helps produce śabdam but also hinders it at times.

Our ancestors learnt about this connection between sound and air through common sense and their powers of observation. In their great wisdom, they devised simple methods to deal with common problems associated with the production of sound by the vocal cords. It is amazing to see how all these seemingly rustic techniques have a sound scientific basis.

Let’s start with the street vendor who covers one of his ears to raise the pitch of his voice while calling out his wares. The wind, entering through the ear can distort the voice and harm the vocal cords. By covering one ear, the air is prevented from entering through that ear.

The absence of the disruptive wind not only makes the sound distinct, but also helps carry it far. If we observe keenly, we will notice that vendors who shout at the top of their voices without covering their ears end up with a hoarse and cracked voice, in addition to suffering from chronic throat trouble.

Another example: when in crowded and noisy places like weddings, public functions or even a railway platform, it is natural to speak at a high pitch to be heard above the din. This can damage the vocal cords and sometimes we ‘lose our voice’, that is, the larynx completely loses its power to produce any sound. Most of us do not know that if one of the ears is covered at such times, our voices can be heard distinctly without our having to raise our voice.

Likewise, a classical vocalist or qawwali singer covers one ear when reaching the upper octaves, to make the voice distinct. Folk and street singers also use this technique. It is mostly the left ear that is covered, while the other hand moves in rhythm with the song or keeps beat.

Now we come to the person trying to call out to someone at a distance. Why is he not covering his ears, but is cupping his hands around his mouth? Here there is no need to cover the ears, even though the wind may enter the ear, as it is not confined to a small space but spread over a wider area. The sound is carried by the air, directed by the cupped hands to the person being called. Do try using these tricks and see how effective they are, to appreciate the wisdom of our ancestors!

In olden days men wielding megaphones made public announcements, especially during elections and such. Here, the sound made by the throat, focused through the funnel (usually made of tin) gets magnified and defies the disturbance of the wind to be clearly heard at a distance.

The Infant’s Cry

I have left the infant’s cry for the next part when I will share my personal interaction with a village elder and his 12-year-old grandson. The boy was baffled by his grandmother’s seemingly contradictory instructions with regard to his baby sister’s crying. If at one time she asked the mother to pick up the crying child, at other times she told her to leave the child alone, even if it cried its heart out.

What was the grandmother’s reason for doing this? Read about that in the next part.