Volume III, Issue 3

Author: Rajeshwari

Continued from Part 9

As we saw in the last part, our ancients saw it fit to connect every tradition and custom to religious and dharmic duties of people, so that they would benefit both physically and spiritually from its practice. Offering physical service or seva at the temples is one such dharmic duty, which is meant for elevating the individual’s consciousness. In this part we shall explore some such seva practices.

Inner Significance of Various Rituals and Ceremonies

To begin with, let us reflect on the deeper reason behind all the outer rituals and ceremonies which we see in our temples. Sri Aurobindo, the Rishi of our times explains this beautifully and precisely in these words:

The image to the Hindu is a physical symbol and support of the supraphysical; it is a basis for the meeting between the embodied mind and sense of man and the supraphysical power, force or presence which he worships and with which he wishes to communicate. . .

The rites, ceremonies, system of cult and worship of Hinduism can only be understood if we remember its fundamental character. . . it has always known in its heart that religion, if it is to be a reality for the mass of men and not only for a few saints and thinkers, must address its appeal to the whole of our being, not only to the suprarational and the rational parts, but to all the others.

The imagination, the emotions, the aesthetic sense, even the very instincts of the half subconscient parts must be taken into the influence. Religion must lead man towards the suprarational, the spiritual truth and it must take the aid of the illumined reason on the way, but it cannot afford to neglect to call Godwards the rest of our complex nature. And it must take too each man where he stands and spiritualise him through what he can feel and not at once force on him something which he cannot yet grasp as a true and living power.That is the sense and aim of all those parts of Hinduism which are specially stigmatised as irrational or antirational by the positivist intelligence.

(Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 147-148)

Gods Also Need Their Rest

Let us first understand that it is not only humans who need to rest to get rejuvenated from unhealthy environment and vibrations. The presiding deities installed in the form of murtis in our temples also need rest to restore their divine power. People go to temples to get the spiritual vibrations of the sanctum. But unfortunately their own vibrations, which may be far from positive, pollute the premises. That is why the deities need to be given periodic rest.

In Part 8 we saw how the deities in the Puri Jagannath temple are taken to an isolated place to be purified, treated and rested before the commencement of the Rath Yatra. This may sound odd to those who don’t understand that the murtis of the deities are invested with jīva when their prana pratishttha is done at the time of their installation. They are not just lifeless ‘idols’ as insinuated by the ignorant.

Incidentally, the COVID-19 pandemic in the last two years ensured that the deities were rested enough to grace the devotees with even more powerful divine vibrations once the temples opened.

Divine Seva to Cleanse Body and Mind

Ancient, big temples in the southern India have a unique way of purifying the temple premises as well as give rest to the deities periodically, which is usually every 12 years. Known as kumbhabhishekam, this consecration ritual follows any structural repairs or restoration work to any area of the temple premises.

The periodicity can be either less or more. Depending upon the damage or wear and tear to the temple and accordingly the frequency of the repair work, it can vary from a few years to more than 12 years. Or as in the case of the Brihadeeswara temple of Thanjavur, it may be just five times in a 1000 years!

Unlike in Puri, where the murtis are removed from the sanctum to be rested, the temples in the south have murtis that are fixed and can’t be moved from the garbhagriha. So they are given rest through another ritual preceding the kumbhabhishekam.

Balayalam and Kumbhabhishekam

Before the temple renovation begins, through a specialised ritual the divine power of the temple’s principal deity as well as other deities are transferred to a kalasha. The kalasha is placed atop the Balalayam, which means a mini aalayam (small temple). This ritual is performed for days, weeks and even months together as per the traditions and customs of that particular temple.

Since the divine presence of the deities are transferred to the holy waters contained in the kalasha, puja is offered to the kalashas and ustava murtis only. During this period, no puja is offered to the main vigrahas. The divine presence of the temple deity continues to be in the kalashas only until it is transferred back to the moola vigrahas, on the day of Kumbabishekam.

The temples are closed for darshan during the period of restoration, with the main tower gate being shut. Only the pujaris and some selected helpers are allowed to do the daily puja and offer other rituals to the deities in the various sannidhis.

In this massive effort of cleaning and renovating, people from all walks of life and from all communities participate with reverence and enthusiasm, spiritually cleansing themselves by doing the required manual labour. They offer their service or seva to the deities and the temple.

Once the renovation and repairs are done, the consecration rituals commence with sahasra kalaśa homam, followed by the kumbhabhiśekam done with the sacred water from the 1000 kalaśas, to the kumbhas at the top of the vimana above the sannidhi and also to the deities in the sanctum.

The Abhiśeka tirtha sprinkled on devotees is a much sought-after grace from the deity. The temple opens to the devotees after this purification ritual, with enhances spiritual vibrations.

Year-long Seva in Temples in Southern India

One can witness another temple-seva all-year round, across the Tamil Nadu in different kshetras and also before and during annual temple festivals. This seva is known as uzhavara thiruppani, which means ‘sacred labour done with the uzhavaram’. It involves physical labour and is included as one of the sadangus or rituals prescribed for human beings in ancient Tamil scriptures.

It was started in the latter part of the 5th century CE, by the great Saivite saint Thirunavukkarasar – one of the four great Nāyaṉmārs, who had spearheaded the Bhakti movement.

Thirunavukkarasar, or Appar, as he was called, always carried an uzhavaram, a cleaning tool that has a small spade at the end of a pole, to clear weeds and other obstacles on the paths leading to the Shiva temples he visited. His uzhavara thiruppani inspires countless devotees even today, to take up the cleaning work in temples, especially dilapidated ones that are in need of repair and maintenance.

Those taking part in this sacred duty, do every kind of cleaning work in and around the temple including sweeping, washing the inner complex at every sannidhi, cleaning and desilting the temple tank and lending a helping hand in the community cooking for annadanam—the last being a regular activity in big temples. The devotees get the sacred prasadam as reward for their seva.

Kar Seva in Temples and Gurudwaras in Northern India

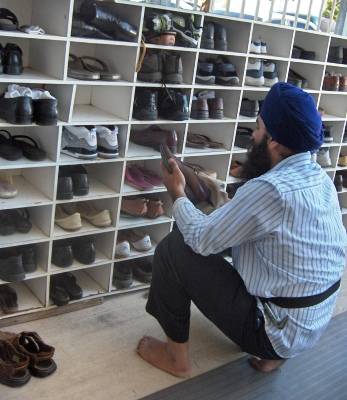

Kar seva is a comparable activity in the temples and Gurdwaras in northern India. One can say that the various sevas at Gurudwaras are the equivalents of uzhavara thiruppani. Like the latter, these are carried out all year round and imbue the volunteer sevadars with spirit of humility, devotion and reverence towards the Supreme.

Seva done to the devotees is seva done to God and therefore no work is seen as menial and even joda ghar seva (cleaning of the shoes of devotees) and toilet cleaning are done by the sevadars with full dedication.

Visiting temples and undertaking uzhavaara pani and kar seva not only increase our inner strength but also give us spiritual energy and physical strength to face any crisis. They imbue the devotees with humility while providing mental and spiritual cleansing. All this is thanks to the wisdom of our ancestors, who had inseparably woven physical and mental health aspects into these activities.

In the next part, we shall learn about the parivrajakas or wanderers who experience physical and spiritual cleansing as they walk, doing seva as they go.

To be continued. . .

Read previous parts

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9

~ Cover image: Rishabh Sharma