Volume V, Issue 11-12

Author: Beloo Mehra

Editor’s note: The author summarises what constitutes an ideal artist as per the Indian cultural tradition. The article gives a broad overview, and focuses mostly on the visual arts. When read in conjunction with other offerings in this issue, a fuller picture emerges. This article does not elaborate upon the education of an artist, a topic left for a future issue. All photographs used in this article are by Madhu Jagdhish, whom we had interviewed for an Insightful Conversation in 2021. He generously shared copies of these photographs with us for that project.

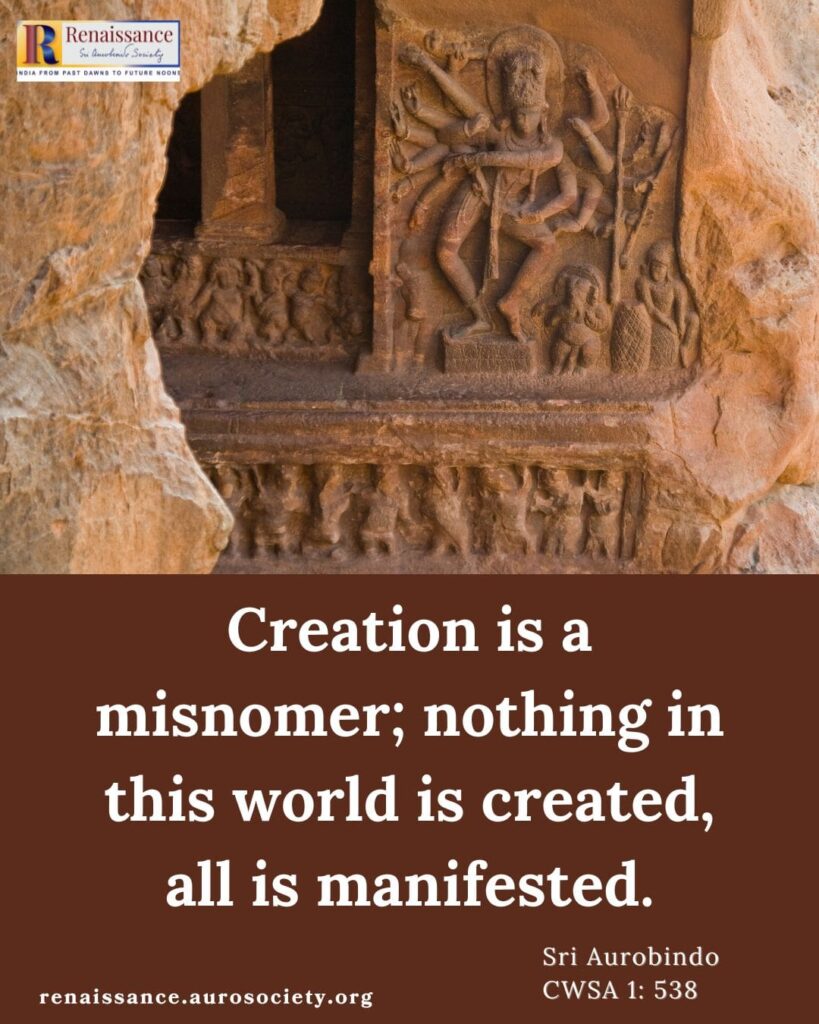

Man creates his world because he is the psychic instrument through whom God manifests that which He had previously arranged in Himself.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 1, p. 538

Kailasanatha temple at Ellora caves is one of those marvels about which one can only say — you have to see it to be believe it! Words fail to describe its grandeur and its beautiful details, its solidity and its delicacy, its fantastic charm and its sublime presence. Perhaps the master-sculptor working on this temple also experienced something similar. (It may be said that this temple carved out of a single mountain is truly a work of sculpture disguised as a work of architecture!) Because after completing this stupendous work he is believed to have exclaimed in wonder — “How did I make it?” This is mentioned in a copperplate inscription.

What do the artist’s words, his expression of amazement tell us? That he was quite aware and conscious that it is not possible for a human to create something so stupendous. That is, unless and until one is working as an active embodiment of some higher creative principle. Stella Kramrisch recounts this story in her book The Art of India Through the Ages. And emphasises that this form of questioning reaffirms the Indian tradition that art is not rooted in the ego, but something beyond or higher than the ego.

See more of Madhu Jagdhish’s heritage photography HERE.

Where exists the art?

The art exists in the phase of consciousness that precedes the separateness of the ego and is itself the very stuff of consciousness. Sāṃkhya darśana calls this phase of consciousness as Mahat, meaning The Great One. It is the plane where there is no differentiation between subject and object. When the subject-object content functions as the active agent, it is the intellect (buddhi).

Further modifications begin to take place in three lines by three different kinds of vibrations or oscillations. These correspond to the three gunas — the sattva, rajas and tamas. When the mahat is disturbed by the three parallel tendencies of a preponderance of tamas, rajas and sattva, there is the emergence of ahaṃkāra. This is when the ‘I’ sense or the ego appears. And with it we have the outside world and a sense of separateness between the ego and the Great One.

Stella Kramrisch explains the relation of art to this darshana,

Art originates in mahat and evolves in buddhi. Subsequently, the ego apprehends and, according to its limitations, modifies the work in progress, but it has no part in the creative process. In amazement, the ego recognizes the creative spirit when Viśvakarmā has finished his work.

~ The Art of India Through the Ages, p. 14

The individual artist, in this view, appears as separate or parted from ‘The Great One’. When poised in ordinary consciousness, the artist is not in a supra-personal communion. But the artistic tradition of India enjoins one to develop the capacity to commune with the Source from which all creativity originates. Only thus can the true art emerge.

All art is interpretation

Sri Aurobindo once said that all Art is interpretation. He added,

“Creation is a misnomer; nothing in this world is created, all is manifested. All exists previously in the mind of the Knower. Art may interpret that which is already manifest or was manifest at one time, or it may interpret what will be manifest hereafter. It may even be used as one of the agencies in the manifestation.

~ CWSA, Vol. 1, p. 538

Our superconscious selves are perpetually in touch with the causal world. The Mother also speaks of as the World of Creation. This world has different zones related to music, painting and literature. The types that exist in these zones of creation manifest in the psychical and become part of our thought, explains Sri Aurobindo. That thought we put out into the material world where it takes shape and body. These are expressed as movements, as institutions, as poetry, Art and Knowledge, as living men and women.

Sri Aurobindo Explains:

The Great Impersonal Creators and Their Living Creations

When art is understood to have its origin and source in the zones high above the artist’s ego, it has important implications. To begin with, we are compelled to ask — what is the artist’s real work in such a conception of art?

“What Nature is, what God is, what man is can be triumphantly revealed in stone or on canvas,” says Sri Aurobindo (CWSA, Vol. 1, p. 451). In other words, an artist must be capable to triumphantly reveal the truth of Nature, God and Man; “triumphantly reveal” and “truth” being the most significant words.

The medium of expression may be stone, canvas, bronze, clay, poetry, prose or anything else. The tradition enjoins an artist to first ‘see’ and ‘identify’ with that which is behind the outer form. The artistic enterprise is not to merely imitate the forms seen in Nature, but rather to transform them in Art. The artist’s expression must be suggestive of the object’s inner truth. An artist is also not bound by the forms that compose the world of gross matter. Though he may use any form as a starting point for a formal expression of what was seen within.

Inner work of an artist

But we must not confuse this inward-oriented approach to art with an ego-centric false subjectivism. That can lead to all kinds of distortions and perversions. The inner work of an artist trained in the Indian school of artistic creative work is akin to Yoga.

To quote from Sri Aurobindo,

Behind a few figures, a few trees and rocks the supreme Intelligence, the supreme Imagination, the supreme Energy lurks, acts, feels, is, and, if the artist has the spiritual vision, he can see it and suggest perfectly the great mysterious Life in its manifestations brooding in action, active in thought, energetic in stillness, creative in repose, full of a mastering intention in that which appears blind and unconscious.

~ CWSA, Vol. 1, p. 451

The Indian artistic tradition requires the artist to develop this inner vision, this yogic capability to identify with THAT which lurks behind the figures, the trees and the rocks. And following a rigorous technique and discipline, he or she expresses that vision in line, form, colour, verse, etc which suggests to the patron, the sahr̥daya, the deeper truth which an ordinary mind may easily miss.

To a modern-rational-westernised mind, imagination is central to all creative pursuits. But an artist grounded in Indian tradition knows that imagination is only a channel. At best it is an instrument of some source of knowledge and inspiration which is greater and higher. The Mother once reminded that in all that one does the most important thing is inspiration.

The Mother Explains:

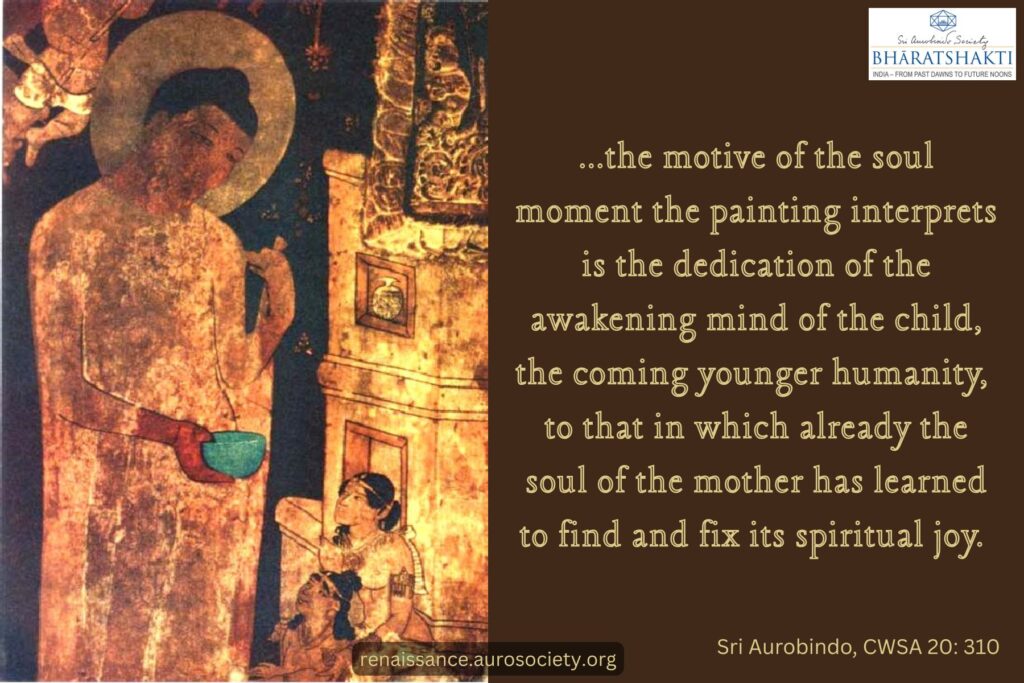

The Relation of Art to Yoga

Equally essential is a contemplative practice of Yoga. An artist aspires to develop a sukshmadrishti (the soul-sight), through which he or she can connect with the ultimate centre of knowledge within. Because there lies the direct and utter vision of the true thing hidden in the forms of man, animal, tree, river, mountain. “It is this samyag jñāna, this sākṣād darśana, the utter, revealing and apocalyptic vision, that he seeks, and when he has found it, whether by patient receptivity or sudden inspiration, his whole aim is to express it utterly and revealingly in line and colour.” (Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 1, p. 464).

Havell also reminds that it was by Yoga, by spiritual insight or intuition, rather than by observation and analysis of physical form and facts, that the Indian sculptor or painter was expected to attain to the highest power of artistic expression.

“Indian art is not concerned with the conscious striving after beauty as a thing worthy to be sought after for its own sake: its main endeavour is always directed towards the realisation of an idea, reaching through the finite to the infinite, convinced always that, through the constant effort to express the spiritual origin of all earthly beauty, the human mind will take in more and more of the perfect beauty of divinity.”

~ E.B. Havell, The Ideals of Indian Art, p. 32

READ:

The Way of the Indian Artist

An artist like a sincere sādhak must practice the discipline of keeping the consciousness uplifted so that it remains ready to receive the inspiration from above. But it is equally important that the artist has the necessary know-how to express what is seen. As the Mother emphasises, “naturally, the execution must be on the same level as the inspiration; to be able to express truly well the highest things one must have a very good technique” (CWM, Vol. 5, p. 69). Thus a rigourous and disciplined training in technique has always been considered essential for an artist.

The True Aim of the Artist

Havell emphasizes that an artist, as per the Indian view, is not seeking to extract beauty from nature. But rather his true aim is “to reveal the Life within life, the Noumenon within phenomenon, the Reality within unreality, and the Soul within matter. When that is revealed, beauty reveals itself” (p. 24).

All nature becomes beautiful for us when we can realize the Divine Idea within it. This is why the tradition insists that in making images of the gods, the artist should depend upon spiritual vision only, and not upon the appearance of objects perceived by human senses. To cultivate this faculty of spiritual vision and the powers of intuitive perception was the main endeavour of the Indian artist and craftsman in the golden age of Indian art and literature.

The Indian craftsman conceives of his art, not as the accumulated skill of ages, but as originating in the divine skill of Viśvakarmā, and revealed by him. Beauty, rhythm, proportion, idea have an absolute existence on an ideal plane, where all who

~ Ananda Coomaraswamy, The Indian Craftsman, p. 73

seek may find. The reality of things exists in the mind, not in the detail of their appearance to the eye. Their inward inspiration upon which the Indian artist is taught to rely, appearing like the still small voice of a god, that god was conceived of

as Viśvakarmā.

The lineage

Over her long history, a variety of schools of temple architecture, sculpture, painting and a large number of other arts and crafts grew and developed to their highest possible expression in various regions of India. But it is also important to recall that the highest of these fine arts in India perfected themselves in the great monasteries and temples, making them into sacred galleries. Ajanta, Ellora, Badami and many other places stand tall witness to this history. Centuries later, these perfected traditions of Indian art practice grew into a science, the records of which are in numerous Śilpa Śāstras.

These Śāstras are a compendium of detailed guidance on all visual and performing arts including sculpture, architecture and painting, music, dance and theater, outlining principles, design rules and standards of artistic creation and construction. Lakṣaṇas or characteristic features of each aspect of the artistic process are clearly enumerated. For example, in its chapter 17, the Nāṭyaśāstra lists thirty-six lakṣaṇas that make a perfect poetic composition (kāvyabandha). These texts not only serve as foundational manuals for ancient Indian artistic practices and rituals associated with them, but also speak of the character development for the śilpi, the artist or craftsman.

Also read:

The Persistent Within the Transient

Along with the detailed Śilpa Śāstras, a well-designed system of śreni-s or artist guilds ensured a thorough and well-grounded education of an artist. An artist or craftsman in India was often part of an unbroken chain of a lineage. Chapter 252 of Matsyapurāṇa1 lists eighteen of such great masters of vāstu kalā (architecture). In other vāstuśastras such as Mānasāra there are mentions of several other names, for some of whom no particular work can be directly associated. But what these names tell us is about the authenticity of an artistic lineage and tradition.

And more importantly, this tradition connects each artist and craftsman straight to the fountainhead, the Creative Principle, to Viśvakarmā, himself, the Lord of all creative work, who is the spiritual ancestor of every artist, every craftsman. This helps keep the artist ‘impersonal’ and ready to work as an instrument of the One True Creative Principle.

Notes

- The Matsyapurāṇa mentions eighteen preceptors of architecture: Bhṛgu, Atri, Vaśiṣṭha, Viśvakarmā, Maya, Nārada, Nagnajit, Viśālākṣa, Purandara, Brahmā, Kārtika, Nandīśvara, Śaunaka, Garga, Vāsudeva, Aniruddha, Śukra and Vṛhaspati. bhṛguratrirbaśiṣṭhaśca viśvakarmā mayastathā// brahmakumāro nandiśaḥ śaunako garga eva ca/ vāsudevoˊniruddhaśca tathā śukrabṛhaspati (Matsyapurāṇa, 252.2-3) ↩︎

~ Design: Beloo Mehra