Volume VI, Issue 6

Author: Narendra Murty

Editor’s Note: In the 1960s and 1970s, with a growing interest in Tantric philosophy and practices, several modern Indian artists got deeply inspired by the philosophical and visual elements of Tantra. The cohesive body of works they created came to be known as Neo Tantra. Notable among these artists were: Biren De, Ghulam Rasool Santosh, Sohan Qadri, P.T. Reddy, K.V. Haridasan, Acharya Vyakul and Mahirwan Mamtani.

Like the Tantric practitioners of earlier times for whom meditation, ritual, art and metaphysics all came together seamlessly in their quest for the Divine, some of these modern artists were also deep into their spiritual and creative sadhana, inspired by Kashmir Shaivism and other Tantric traditions. The core vocabulary of these artists’ works comprised of visual metaphors derived from Tantra including abstractions of deities, ritual diagrams (yantras), chakras, Shiva-Shakti, and mandalas. The noted painter S.H. Raza, while has not been strictly identified with the Neo Tantra genre, was deeply inspired by the Bindu, the singular dot symbol from the Tantra vocabulary.

The author presents here a brief account of Yantras and Mandalas, the artistic expressions often grouped as ‘Sacred Geometry’ that are inspired by the Tantric philosophy.

Introduction

The word Tantra is derived from the root Tan – to expand. It also loosely translates as a system of knowledge or a collection of scriptures. Tantra is a unique philosophy and a system of sadhana that developed independently outside the domain of the six Vedic schools of Darshana, namely Vaiseshika, Nyaya, Mimamsa, Vedanta, Sankhya and Yoga.

As a knowledge system, Tantra is a practical method for the expansion of consciousness and spiritual realisation. While the Vedantic approach focuses on the Brahman, Absolute, Consciousness, Purusha aspect, Tantra’s emphasis is on the Jagat, Relative, Energy, Prakriti aspect of existence. It defines the Absolute and the Relative in terms of Shiva and Shakti.

“One cannot think of Brahman without Shakti or of Shakti without Brahman. One cannot think of the Absolute without the Relative, or of the Relative without the Absolute.

“The Primordial Power is ever at play. She is creating, preserving and destroying in play, as it were. This Power is called Kali. Kali is verily Brahman, and Brahman is verily Kali. It is one and the same Reality. When we think of It as inactive and not engaged in the ats of creation, preservation and destruction, then we call It Brahman. But when it engages in these activities, then we call It Kali or Shakti. The Reality is one and the same…”

~ Sri Ramkrishna, The Gospel of Sri Ramkrishna

Watch:

Worship of the Divine Mother in Integral Yoga

The dynamic, kinetic, Energy aspect of existence is represented by the Divine Mother, Devi or Shakti. And wherever Devi is represented, the existence of Shiva is also implied because they are one and inseparable – like milk and its whiteness or fire and its heat.

This article explores how Tantric concepts have been expressed in art. Tantric Art finds expression in the broad categories of Sacred Geometry comprising Yantras and Mandalas, representation of Kundalini and Chakras, Polarity/Duality, and ten emanations of the Divine Mother, the Dasa Mahavidyas. The focus of this article is limited to Yantras and Mandalas.

“Tantric Art is specially intended to convey a knowledge evoking a higher level of perception and taps dormant sources of our awareness…. Apart from aesthetic value, its real significance lies in its content, the meaning it conveys, the philosophy of life it unravels, the world-view it represents. In this sense Tantra Art is visual metaphysics.”

~ Ajit Mookerjee and Madhu Khanna, The Tantric Way: Art, Science, Ritual, 1977, p. 41

Yantras

A Yantra is essentially a geometrical pattern which includes vertical and horizontal lines, triangles, circles, squares and dots. Yantras are used for visualization and as aids to concentration and meditation. In his book, The Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization, Heinrich Zimmer writes that Yantras act as support for meditation. As a representation of some personification or aspect of the divine, a Yantra acts as a “model for the worship of a divinity immediately within the heart, after the paraphernalia of outward devotion (idol etc.) have been discarded by the advanced initiate.” He adds,

“A Yantra is an instrument designed to curb the psychic forces by concentrating them on a pattern, and in such a way that this pattern becomes reproduced by the worshipper’s visualizing power. It is a machine to stimulate inner visualizations, meditations, and experiences.”

~ 1972, p. 141

A distinguishing feature of all Yantras is their geometric pattern and the absence of iconographic representations. A Yantra has also been referred to as an energy pattern or a power-diagram.

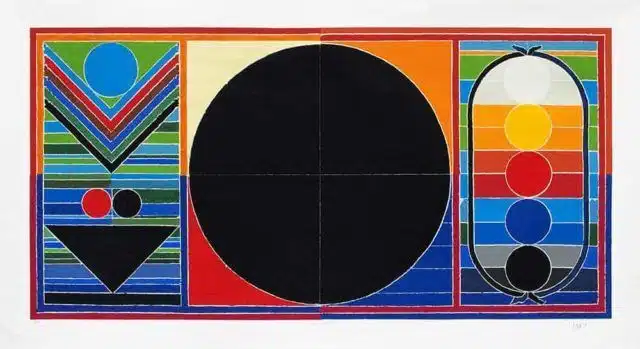

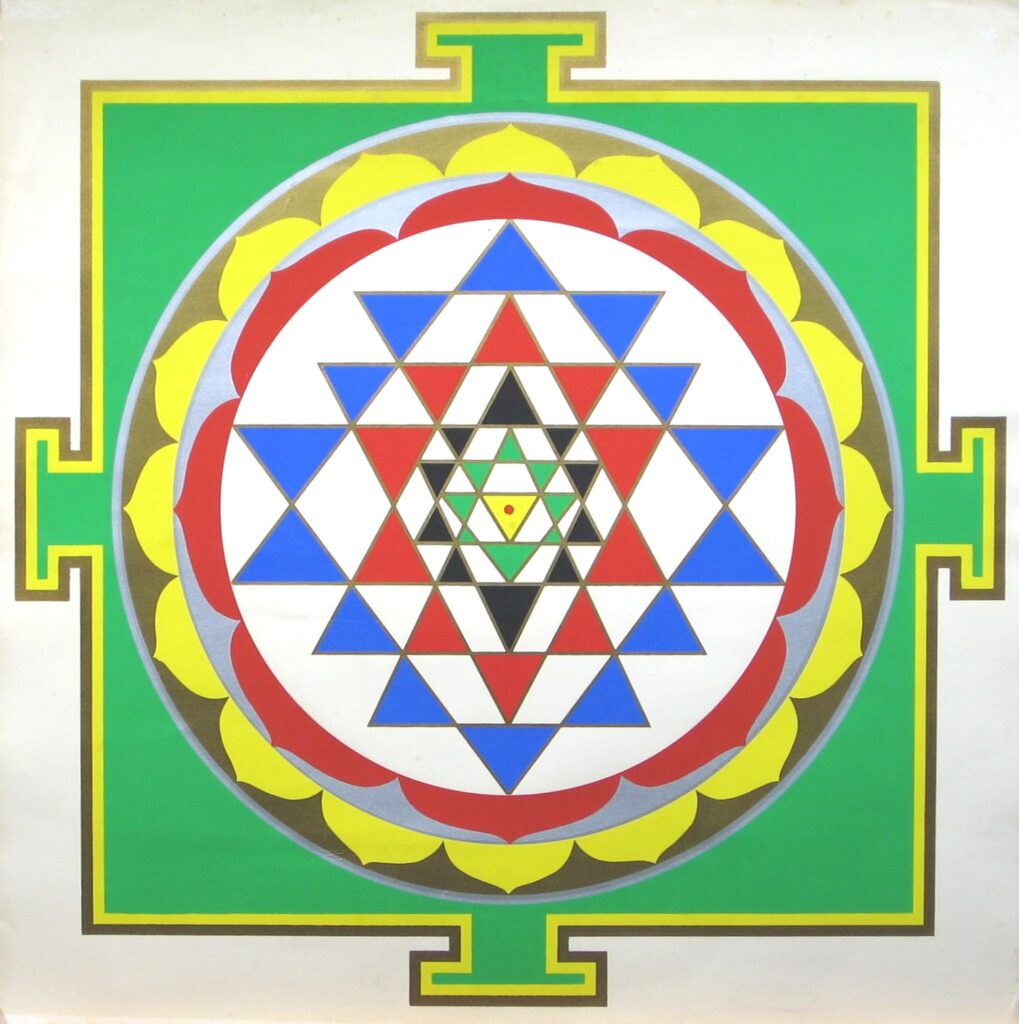

Sri Yantra with correct traditional colors according to Harish Johari. The artwork is a silkscreen print made in 1974 at the Tantra Research Institute in Oakland, California. (source)

***

The most well-known representation of this kind of geometrical pattern is the Sri Yantra. It is composed of 5 triangles of progressively larger size representing the female Energy aspect (Shakti) and 4 triangles representing the male Consciousness aspect (Shiva) of the Divine. The Shakti triangles point downward and the Shiva triangles point upward. The intersection of these 9 major triangles called Yonis or wombs, creates 43 small triangles. Each of these triangles is the dwelling place of a deity.

The central point Bindu represents the great goddess Tripura Sundari to whom the yantra as a whole is dedicated. This complex figure is enclosed by square design and is surrounded by 3 concentric circles called tri vritta where the outer circle encloses 16 lotus petals and the inner circle 8 petals and each petal contains one of the Kamakala deities. These represent the impulses of desire born of the inherent nature of Prakriti which create a throb (spanda) which vibrates as sound (Nada). Overall, Sri Yantra symbolizes the various stages of Shakti’s descent in creation.

Similarly, in the Kali Yantra, the circle is Avidya (ignorance), the 8 petalled lotus is the eight-fold Prakriti consisting of the five elements, the mind, intellect and ego. The 5 triangles represent the five sense organs or the organs of action or the five pranas. And the central point, the Bindu in this case, is pure consciousness reflected in Maya (Bija or the seed of creation). Such are the mystical dimensions of the Yantras.

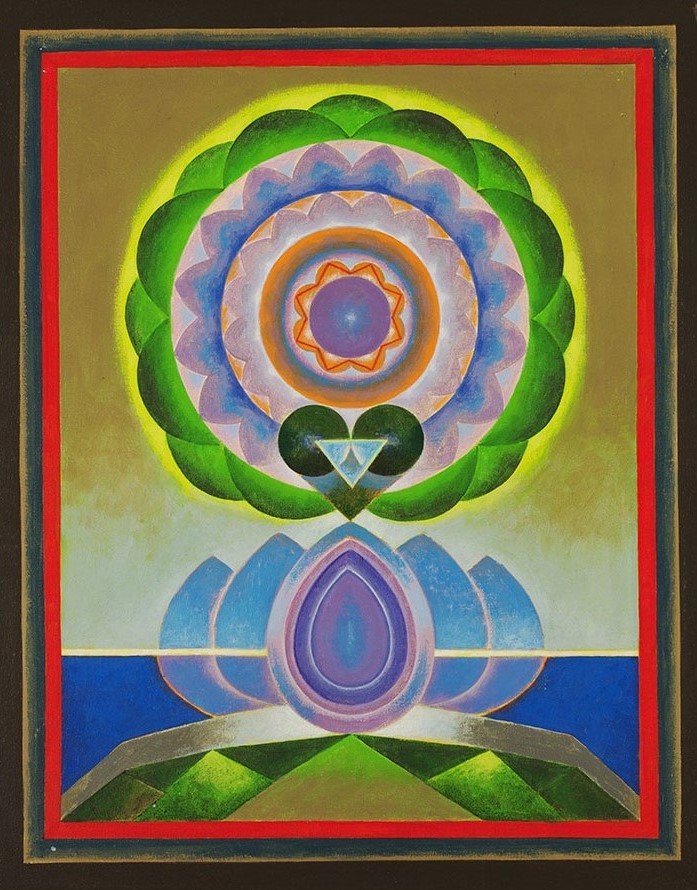

Mandalas

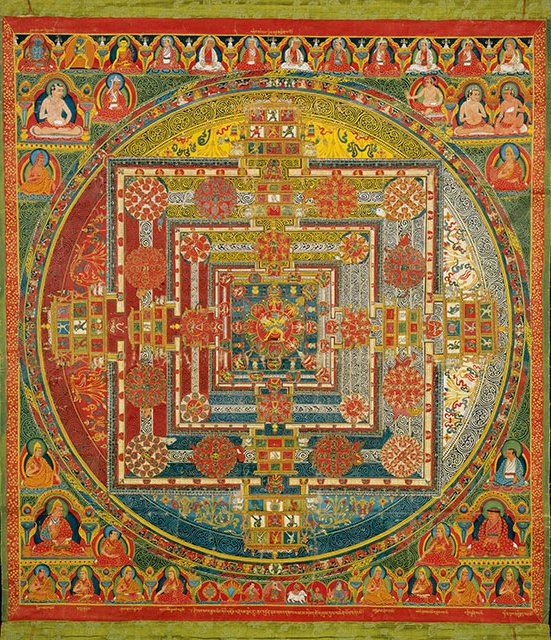

A mandala, simply speaking, is a sacred geometric space. Mandalas often consist of a series of concentric circles enclosed by a square, which in turn has a circular boundary. The square contains a gateway in the middle of each side. Traditionally, mandalas have been drawn by spiritual masters and aspirants as a practice of meditation and as a form reflecting universal consciousness.

Mandalas are often drawn on the ground using multi-coloured sand. But nowadays scroll paintings are also common and many of them are used to adorn the walls of the parlours of our modern-day apartments. A well-known mandala known as the Vajradhatu Mandala is seen in the monastery at Tabo. (SEE HERE).

***

Ajit Mookerjee and Madhu Khanna explain the process of drawing the mandala in The Tantric Way:

“The mandala indicates a focalization of wholeness and is analogous to the cosmos. As a synergic form it reflects the cosmogenic process, the cycles of elements, and harmoniously integrates within itself the opposites, the earthly and the ethereal, the kinetic and the static. The circle also functions as the nuclear motif of the self, a vehicle for centering awareness, disciplining concentration and arousing a state conductive to mystic exaltation. Each of the five component parts of the mandala – the four sides and the centre – is psychologically significant; they correspond to the five structural elements of the human personality…

“Like all Tantric activity, the process of drawing the mandala is an exercise in contemplation, an act of meditation… To evoke the universe of the mandala with its wide-ranging symbology accurately, the artist has to practise visual formulation…. The image, like a mirror, reflects the inner self which ultimately leads to enlightenment and deliverance. In Tibet, the actualization of this awareness is known as ‘liberation through sight’. The act of seeing, which is analogous to contemplation, is in itself a liberating experience.”

~ pp. 64-66

Mandalas are also incorporated in elaborate scrolls and other artworks done as exercise in contemplation. Nature too abounds with forms resembling a mandala. Educators and healers today are also using mandala work in their contexts to facilitate concentration and quietude.

Read:

Practices involving mandalas in classrooms

~ Artwork selection and web design: Beloo Mehra