Volume 1, Issue 5

Author: Beloo Mehra

Editor’s Note: The author highlights main contributions of the book in two key areas: a) menstruation related discourse in India, and b) connection between culturally grounded understanding of menstruation and a woman’s sense of identity and self-worth.

Menstruation is a natural biological process that women undergo during a major period of their lives. Because of its connection with fertility and pregnancy, menstruation is closely linked with womanhood suggesting some of the fundamental differences between men and women at many levels including physical, emotional and psychological.

It is no wonder then that over the ages, menstruation and related practices have figured significantly in the evolving perceptions of different societies and cultures across the world toward fertility, sexuality, women, man-woman relationships, and the place and role of women in society as a whole.

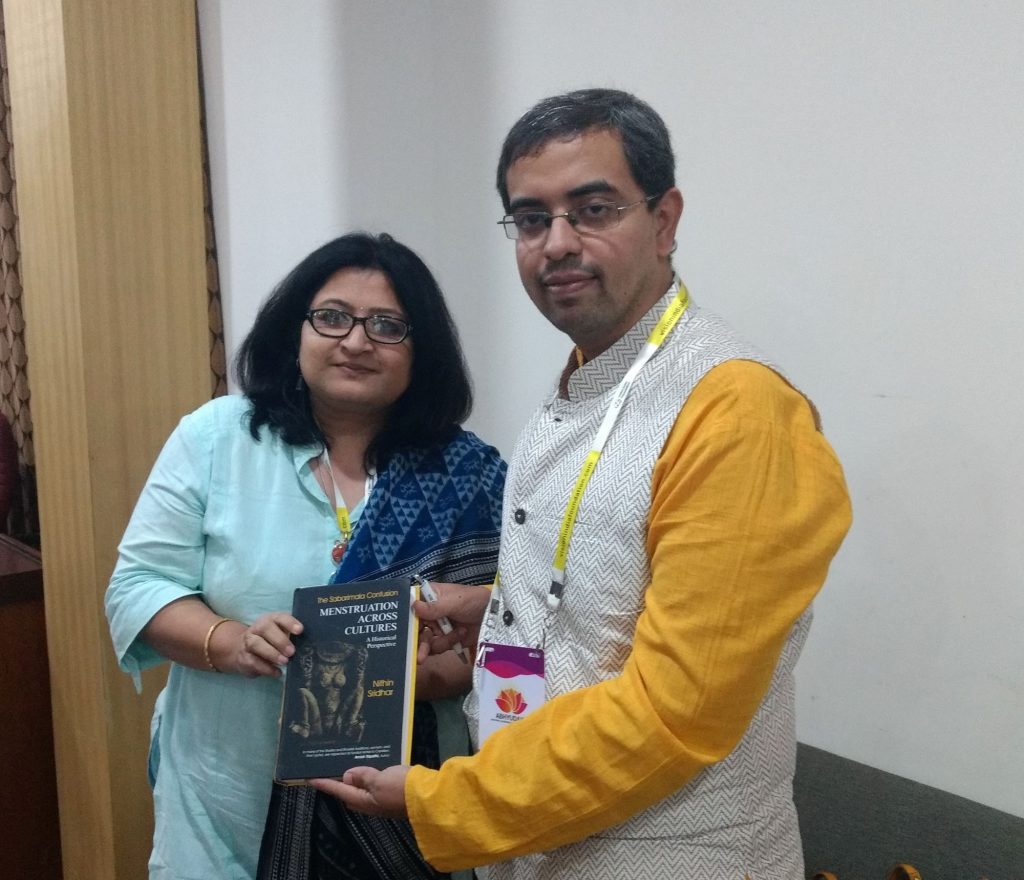

In our ‘Book of the Month’ for July 2019 issue, we feature an important book on this topic of menstruation that has come out in the recent times. “Menstruation Across Cultures: A Historical Perspective” by Nithin Sridhar is important for several reasons, but I will mention only a few in this review.

Instead of giving a chapter-by-chapter look at the key ideas from the book, my purpose and focus in this review is somewhat different. I wish to point out why I think this book must be read by all those interested in gender studies, and especially Indian women.

While speaking of some important points covered in the book, my main purpose is to highlight what I think are some of the main contributions of this book, in two key areas: a) menstruation related discourse in India, and b) connection between culturally grounded understanding of menstruation and a woman’s sense of identity and self-worth.

Significance of the Book

1. This comprehensive book gives a very wide and deep cross-cultural understanding of how different religious and cultural traditions have viewed and discussed menstruation over time. It not only examines the differences but also highlights the commonalities in some of the perspectives across various traditions.

This point about commonalities but with some subtle differences must not be missed. For example, Sridhar carefully analyses the deeper meaning of the concept of Ashaucha from within Hindu view and compares it with the concepts of Miasma and Niddah when explaining how the idea of impurity can be understood from different perspectives. He speaks about the different ways different traditions explain this notion of ‘impurity’ and ways to address it.

2. In addition to describing how the topic of menstruation has been addressed in various Indic religious-cultural traditions, namely Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, the author also provides a good view of the ways in which various texts of Abrahamic faiths – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – deal with this important aspect of women’s life. There is also a description of how different indigenous communities in Africa, Americas and Australia have addressed this topic of menstruation in their cultural contexts.

3. When dealing with the Hindu view of menstruation, Sridhar provides evidence from several texts such as Vedic Samhitas, Brahmanas, Dharmashastras, Kamashastras as well as texts on Ayurveda and Jyotisha. In the sections on other religious traditions also, we see detailed evidence from a variety of ancient texts and scriptures as well as contemporary research done on those texts.

There is plenty of evidence from ancient medical texts from different civilisations.

For the sheer amount of textual evidence one can find in this book, along with its appropriate interpretation, it is a source of great information and a valuable resource for researchers working in the area of women’s reproductive health and/or related social-cultural aspects.

4. Many of the ongoing ‘menstrual health’ campaigns in India led by NGOs – Indian or Western – end up reinforcing the assumption that most girls and women in traditional societies such as India have to suffer many restrictions because of several cultural beliefs and practices related to menstruation.

There is a tendency to put down certain cultures and religions on the basis of such assumptions and preconceived biases resulting from either lack of proper cultural sensitivity and awareness or simply a disinterest to study deeper the reasons behind some of the cultural beliefs and practices related to menstruation.

5. After going through Sridhar’s book, especially the sections where he provides a cross-cultural view of menstruation related practices and restrictions, any thinking reader can’t help but wonder why in the frequently occurring controversies and popular debates surrounding the topic of ‘menstrual restrictions, taboos and superstitions’ in some sections of Indian society, the focus is deliberately kept only on the ‘Hindu view.’

Such an exclusive focus on Hinduism alone ends up keeping its practitioners perpetually in a defensive mode as they feel tempted to respond to baseless allegations of being superstitious, oppressive toward women, misogynist etc. These controversies and debates hardly ever bring up any mention of how other religious traditions prevalent in India dealt with the issue of menstruation and what kind of restrictions or taboos were/are prescribed for women in those traditions.

6. For example, there is sufficient academic research on Judeo-Christian view of menstruation – and Sridhar cites some of this in the book – which gives clear evidence of how the notions of impurity and ‘original sin’ were the lenses through which women’s menstruation was seen. (The Islamic view of menstruation is more or less similar to the Judeo-Christian view, with a few minor differences.)

These original notions later became easy theological tools to facilitate a sociological view of ‘otherness’ resulting in not only lowering the status of women in the society by considering them inferior but often also led to grievous violence against women (such as the infamous ‘witch-hunting’). There are also clear restrictions prescribed by all Abrahamic religious traditions.

7. But ask any modern ‘educated’ women in India – regardless of religious affiliation – about what she knows about any ‘menstrual restrictions’ you will most likely hear things such as – “not allowed to go to the temple, not allowed to do any puja even at home, not allowed to touch the murti of the deity, etc” – all associated with the Hindu view.

It would be an interesting sociological study to conduct, I believe. But even without doing one, I am inclined to suggest that chances of hearing something like – “not allowed to touch the Holy Quran, not allowed to take sacrament at church” are very minimal.

This has to be the outcome of a deeply asymmetric modern sociological discourse in our country around the topic of menstrual restrictions and taboos, where Hinduism has been so frequently and repeatedly attacked for some of its alleged ‘discriminatory’ practices that people have stopped asking the question whether other religions ever had similar notions of menstruation related practices.

8. Because of this asymmetric popular discourse in India with only Hinduism under the ‘sociological gaze’ of the feminists and activists, (and connecting it all with the larger issue of gender equality), many young women and men while being raised in Hindu families, still end up developing a deep sense of alienation and disconnect from their cultural and religious backgrounds. This is a serious concern for the overall well-being of the society.

9. In this regard, the book by Nithin Sridhar dispels much ignorance by giving a very wide cross-cultural view of this topic of menstruation and helping the reader see differences, commonalities, and also the evolution over time of some of the beliefs, knowledge, practices and restrictions related to menstruation and fertility.

This last part is done remarkably well by including sufficient details about how menstruation was addressed in some of the ancient civilisations – Greek, Roman, Mesopotamian, Egyptian.

10. When dealing with the Hindu view of menstruation, there is ample discussion on how the overall feminine principle of creation, including women’s fertility and menstrual cycle, continue to be not only acknowledged but also honoured and celebrated across the various Hindu traditions. The readers learn about the specific temple celebrations that occur on a regular basis across the country.

The readers also get a glimpse of various cultural practices from different regions of India which celebrate menarche, the onset of menstruation. These are all part of the ‘living’ culture of India, and this is one of the key learnings a reader takes from this book.

Read more in the Book of the Month

11. One of the important discoveries a reader makes when going through the section on ancient civilisations concerns the similarity with the Indic/Hindu view of menstruation. These civilisations also assigned a sense of sacredness to the female reproductive cycle, which was reflected in their views on menstruation (including having female deities associated with menstruation and fertility).

This is significant because in many ways these ancient civilisations were the pagan precursors to what later became the cultural traditions associated today with the three dominant monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam. With the mass spread of Abrahamic and monotheistic view of Religion, as the older pagan belief systems and practices were completely destroyed, this idea of ‘sacred feminine’ also started disappearing in these cultures.

12. Over time, as a result of the ‘scientific enlightenment,’ which was in many ways a revolt against the Religion, any deeper cultural view of female reproductive cycle including menstruation was shunned as ‘superstition’ or ‘taboo.’ The result today is a completely ‘rational-materialistic-scientific’ view of menstruation which is now pitted against any ‘cultural’ knowledge about it.

This ‘scientific’ view of menstruation is now the predominant ‘knowledge exported under the guise of “promoting menstrual health and hygiene in the developing world” by the activist-lobbies of the West and their counterparts in India.

13. It is no surprise then that today many young Indians, in their zeal to ape everything Western and confusing Westernisation with modernity, feel a sense of strong disconnect from their cultural backgrounds. Much of the ignorance exists simply because our present ‘modern’ education has conditioned us to think that only a materialistic-rationalistic view toward life, identity, health, gender, individualism, society, culture, religion, etc. can be a modern and hence universally generalizable view.

As a result, every other ‘cultural’ or ‘traditional’ view toward any of these things is considered just some ‘localised’ variant, not at all relevant for our modern times and contexts.

14. “The obsession with imparting knowledge about menstruation to youngsters in a purely biological manner to the exclusion of the cultural experience, means that young girls are denied the opportunity to find a positive meaning and relevance of menstruation in their lives….

Since modernity posits that to be truly human, creative, rational, is not to be ‘enslaved’ by our biology, women are expected to free themselves of the enslavement of menstruation using drugs, tampons, sanitary pads etc.” (Sridhar, p. 292)

15. Nithin Sridhar’s well-researched book, by facilitating a deeper awareness about the historical view of menstruation across various cultural and religious traditions, acts as an important correction to the asymmetric discourse that is behind the cultural alienation. It has the potential to address some serious misconceptions about cultural views related to the larger issue of gender equality as reflected through the topics of sexuality, fertility and menstruation, which can help prevent further cultural-uprooted-ness among younger generations of Indians, particularly young girls and women.

The book compels the readers to first deeply examine and understand the essence of certain traditional practices and customs before getting into a conversation about how these practices can or should change over time.

16. In the past few years, we have seen a great push to promote menstrual hygiene and health in countries like India. In addition to the campaigns being led by various NGOs and other social agencies, the United Nations too has been supporting this important cause. However, it is equally important to situate these efforts in the appropriate cultural and sociological contexts.

For example, behind many of the programmes there is an underlying assumption that girls and women in developing countries generally have poor menstrual health often resulting from lack of proper education, lack of availability of menstrual hygiene products, and the continued use of several non-scientific traditional menstrual practices. However, several comparative research studies find that this is not the case.

Some field studies have also revealed that often the use of traditional menstrual hygiene practices by girls and women in many parts of rural India not only makes much greater sense for various reasons but also does not really have any adverse effect on the overall menstrual health.

17. The book helps readers move away from a superficial and sensationalist view of this sensitive topic of menstruation and menstrual health. It makes them more informed and sensitive about menstruation and its connection with overall health and well-being of girls, women, and ultimately the health of the society itself.

It facilitates a critical and open-minded reader’s examination of some of his or her own biases and wrong assumptions about menstruation related practices in Hinduism resulting from either misinformation or misperception or both.

The chapter which compares some of the ‘modern’ menstruation attitudes with the traditional Hindu attitudes is another important contribution which dispels many myths prevalent in modern minds about the ‘regressive’ nature of tradition versus the ‘progressive’ modern ideas. In this regard, the ‘Last Words’ in the book written by Madhu Kishwar make for an important reading.

18. Another key strength of the book is that it helps readers gain a deeper physiological and psychological understanding of menstruation and its related practices by bringing in valuable insights from Yogic and Ayurvedic traditions, and providing logical explanations for these practices. These insights on menstruation practices, restrictions and common menstrual disorders have a direct connection to most practical topics related to menstrual health and hygiene.

Here we also find Sridhar citing a few important scientific studies that have been done to study the health benefits of the traditional Ayurvedic menstrual regimen called Rajaswala Paricharya. The findings suggest great benefit of following some of the prescribed restrictions, especially concerning diet, physical exertion, and sleeping routine.

19. One of the key insights an Indian woman can carry with her after reading this book concerns the comprehensive view of menstruation that her culture has evolved, a view in which impurity and sacred-ness complement each other.

Menstruation, in Hindu view, is seen as a natural process of self-purification and austerity for women, which is the basis for the specific do’s and don’ts as prescribed in the Rajaswala Paricharya according to Ayurveda.

Similarly, the restrictions for performing any religious activity or engaging in spiritual pursuits during menstruation have been carefully explained using the insights from physiology as explained in Yogic and Ayurvedic traditions. This can help Indian girls and women develop a deeper cultural appreciation and understanding of menstruation and fertility, something that so far, they must have only seen as a mere biological process.

20. By inculcating a profound cultural sensitivity toward the topic of menstruation and related aspects, the book has the potential to facilitate the self-development of the younger generations, particularly women, in order for them to exercise greater personal responsibility toward their menstrual health and hence their role in creating a more conscious humanity.

Through its examination of the deeper psychological and cultural insights on matters concerning menstruation, fertility and womanhood, the book compels a conscious reader to explore the deep connection between menstruation and an overall sense of identity-formation and self-worth among girls and women, and its impact on the overall ‘well-being’ of the society.

On a Personal Note

A few years ago, I had read the author’s earlier six-part series of articles on Hindu view of menstruation. That was highly informative and educational. In an interaction with the author back then, I admitted that throughout my ‘modern’ education I was hardly told anything as a young girl about this crucial aspect of womanhood as understood in Indian cultural context.

I didn’t remember any conversations about the deeper reasons why certain menstruation related practices and customs came into being. I only remembered rebelling against a few things when I didn’t find adequate and convincing answers either at school or at home.

In fact, these things were hardly discussed openly, and that in itself is the result of what Sridhar discusses as the outcome of removing any cultural association with menstruation under the garb of modernity and its biological-scientific view of menstruation and fertility.

I can almost certainly say that this has been the experience of many women of my generation who grew up in urban India. I can also confidently add that if a deeper cultural dimension to menstruation and fertility would have been part of my education, I and many others like me would have developed a much stronger sense of self-worth as young girls.

This is especially true of those of us who came of age in places such as Delhi which have their own issues with cultural-uprooted-ness. For so many of us, learning about our cultural traditions at this point in our lives is a re-discovery of our ‘selves’ in so many ways.

Reading about cultural perspectives and attitudes toward menstruation – both in the Hindu view as well as in other religious/cultural traditions, also brings up another thought for me.

And this may have to do with the fact that having dealt with my own share of issues and problems with menstruation and fertility in my 20’s, 30’s and 40’s, and having reached a certain age and entered a different phase of womanhood, I am also beginning to see the wisdom in a different view of how young girls in today’s India can be made to develop a healthier understanding of their bodies and natural processes of menstruation.

This is not to deny the value of teaching them about a deeper Indian cultural view of menstruation and its psychological basis; indeed there is great value in doing that, and it must be done. But there is also a need to move beyond a gendered view of life and nature, and bring into the awareness of young girls and women that they are more, a whole lot more than the natural processes of their physical bodies.

This requires that they begin to learn how to master, in an organic way, any usual discomfort they might experience during their monthly periods. This can be done as part of their overall physical training with the larger aim of gradually making one a master of one’s physical body and its limitations, its natural impulses and urges.

The Mother of Sri Aurobindo Ashram once spoke to girls and women in the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education about this very topic. I share below part of her comments which speak of gradually seeing beyond the limits of the material external being. She says:

It is true that we are, in our inner being, a spirit, a living soul that holds within it the Divine and aspires to become it, to manifest it perfectly; it is equally true, for the moment at least, that in our most material external being, in our body, we are still an animal, a mammalian, of a higher order no doubt, but made like animals and subject to the laws of animal Nature.

You have been taught surely that one peculiarity of the mammal is that the female conceives the child, carries it and builds it up within herself until the moment when the young one, fully formed, comes out of the body of its mother and lives independently.

In view of this function Nature has provided the woman with an additional quantity of blood which has to be used for the child in the making. But as the use of this additional blood is not a constant need, when there is no child in the making, the surplus blood has to be thrown out to avoid excess and congestion. This is the cause of the monthly periods.

It is a simple natural phenomenon, result of the way in which woman has been made and there is no need to attach to it more importance than to the other functions of the body. It is not a disease and cannot be the cause of any weakness or real discomfort.

Therefore, a normal woman, one who is not ridiculously sensitive, should merely take the necessary precautions of cleanliness, never think of it any more and lead her daily life as usual without any change in her programme. This is the best way to be in good health.

Besides, even while recognising that in our body we still belong dreadfully to animality, we must not therefore conclude that this animal part, as it is the most concrete and the most real for us, is one to which we are obliged to be subjected and which we must allow to rule over us.

Unfortunately, this is what happens most often in life and men are certainly much more slaves than masters of their physical being. Yet it is the contrary that should be, for the truth of individual life is quite another thing.

We have in us an intelligent will more or less enlightened which is the first instrument of our psychic being. It is this intelligent will that we must use in order to learn to live not like an animal man, but as a human being, candidate for Divinity.

And the first step towards this realisation is to become master of this body instead of remaining an impotent slave. One most effective help towards this goal is physical culture.

(CWM, Vol. 12, pp. 291-292)

I see this view not in opposition to all that is presented in Nithin Sridhar’s well-researched book. I rather see it as a complementary view to that, in the sense that it helps to bring in a more non-gendered view and perhaps can help girls and women develop a more balanced attitude about themselves – they are not only girls and women (a view which is generally focused around their physical bodies and how different they are from boys and young men), but that they are first and foremost individual beings in each of whom there is a unique spark of the Divine Presence enwrapped in physical, mental and vital sheaths.

By taking away the exclusive focus from physical bodies and shifting it somewhat to a deeper psychological attitude, this view has the potential to open the girls’ and women’s consciousness toward a higher evolutionary purpose of life.

What I also find deeply comforting is the last word of the Mother in the same passage where she gives a note of caution:

“One word to finish: I have told you these things, because you needed to hear them, but do not make of them absolute dogmas, for that would take away their truth.” (CWM, Vol. 12, p. 297)

About Nithin Sridhar:

With a degree in civil engineering, and having worked in construction field, Nithin Sridhar passionately writes about various issues from development, politics, and social issues, to religion, spirituality and ecology. Based in Mysore, he is currently pursuing Masters in Philosophy from Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi. He is Editor of IndiaFacts, an online portal focused on Indian history, culture and philosophy.