Volume VII, Issue 1

Author: Beloo Mehra

Editor’s Note: Literature, like other creative pursuits, can be an important medium to orient the society towards a higher new vision, a greater ideal. It can also progressively shape the collective mind through its sustained influence. Sri Aurobindo spoke of “the awakening and stimulating influence” of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee on the national mind. “Young Bengal gets its ideas, feelings and culture not from schools and colleges, but from Bankim’s novels and Robindranath Tagore’s poems”, he once wrote (CWSA 1: 118).

About Bankim’s immense contribution to Bengali language and literature, Sri Aurobindo remarked that he “divined the linguistic need of his country’s future” (CWSA, 1: 639). Through his pen Bengali language became a means “of expression capable of change and expansion” and “by which the soul of Bengal could express itself to itself”. Bankim gave to his country the religion of patriotism through his characters who were workers and fighters for the motherland, who demonstrated immense moral strength, self-discipline and organisational capabilities, and infused religious feeling into their patriotic work. “Of the new spirit which is leading the nation to resurgence and independence, he is the inspirer and political guru,” wrote Sri Aurobindo (CWSA, 1: 640).

The essay featured in the current issue (in 2 parts) highlights Bankim’s poetic style, vivid imagery, and nuanced portrayal of feminine character, particularly Matangini, whose inner conflict symbolizes India’s struggle between tradition and modernity. Drawing on Meenakshi Mukherjee’s and Makarand Paranjpe’s analyses, the essay interprets the novel as an allegory of emerging national consciousness, emphasizing its relevance to India’s ongoing quest for cultural integration and progress. A longer version of this article was first published in New Race: A Journal of Integral and Future Studies, April 2015, Volume I (1), pp. 54-59.

In December 1932, in a letter, Sri Aurobindo wrote that Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (Chattopadhyay) is and “will always rank as one of the great creators and his prose stands among the ten or twelve best prose-styles in the world’s literature” (CWSA, 27: 547).

He was indeed a literary pioneer in Bangla, his native language, but not many may know that he also gave us the first Indian novel written in English, titled Rajmohan’s Wife. Published in 1864 this was the first and the only novel written by Bankim in English. This is probably the first English novel in all of Asia.

This work has been considered a ‘false start’ by some commentators of Bankim’s work, and has often been ignored by those interested in Indian writing in English. After Rajmohan’s Wife, Bankim never wrote any fiction in English and wrote only in Bangla, and went on to make gigantic literary contributions.

In this essay, I take a closer look at a few aspects of this novel in the context of their relevance for a student of modern Indian society and culture. Sri Aurobindo’s vision for an Indian cultural renaissance and his insights into the deeper significance of Bankim’s literary work give my ‘reading’ the necessary interpretive framework. It must also be added that Sri Aurobindo also saw Rajmohan’s Wife as the author’s false start, primarily because he thought that Bankim came into his originality with his writing in Bangla, his mother tongue1.

Poetry of Life

One of the things I find most captivating in the novel is a “deep feeling for the poetry of life and an unfailing sense of beauty” — what Sri Aurobindo remarks as the distinguishing marks of Bankim’s style (CWSA, 1:109). The following passage perfectly illustrates how the novelist’s rich and vivid description paint a beautiful and living picture for the reader.

The recent shower had lent to the morning a delightful and invigorating freshness. Leaving the mass of floating clouds behind, the sun advanced and careered on the vast blue plain that shone above; and every housetop and every treetop, the cocoa palm and the date palm, the mango and acacia received the flood of splendid light and rejoiced.

The still-lingering water drops on the leaves of trees and creepers glittered and shone like a thousand radiant gems as they received the slanting rays of the luminary. Through the openings in the chick-knit brought of the grooves glanced the mild ray on the moistened grass beneath.

The newly awakened and joyous birds raised their thousand dissonant voices, while at intervals the papia sent forth its rich thrilling notes into the trembling air. Light fleecy clouds of white wandered in the solitude of the now purified blue of the heavens, which were fanned by a light breeze that had sprung up to shake the pattering drops from the pendant and wooing boughs.

What a delightful picture of a fresh morning after a rainy night! The clear blue sky, the pleasing sounds of the birds, the moistened grass, and still-lingering water drops on leaves – beauty all around, loveliness that pleases and delights.

Interestingly, this passage comes right after the description of a rather ‘heavy’ sequence in which a gang of dacoits is running around in the rain and feverishly hunting down the wife of one of the gang members who might have been a spy and an informer.

All traces of any inkling of suspense, horror or anxiety that the reader might have felt while reading the preceding passage were completely washed clean by this delightful portrayal of after-the-rain-morning that brings with it a new hope and a new adventure in life. This is perhaps an appropriate example of what Sri Aurobindo describes as the novelist’s “keen sense for life, and the artist’s repugnance to gloom and dreariness” (CWSA, 1: 96).

Portrayal of Women Characters

Another prominent aspect of the novel is Bankim’s portrayal of the characters, particularly the women characters. This aspect is sufficiently analysed by Meenakshi Mukherjee in her Afterword in the Penguin Edition. But she primarily uses the familiar and academically-acceptable critical lenses such as social conformity, morality, virtue and honour in man-woman relationship, narrow confines of domesticity, and silencing of women.

Informative as these viewpoints may be, they still fail to do full justice to the beauty of Bankim’s insights into the feminine character. The following passage serves as an example.

‘You weep!’ said Madhav. ‘You are unhappy.’

Matangini replied not, but sobbed. Then, as if under the influence of a maddening agony of soul, she grasped his hands in her own and bending over them her lily face so that Madhav trembled under the thrilling touch of the delicate curls that fringed her spotless brow, she bathed them in a flood of warm and gushing tears.

‘Ah, hate me not, despise me not,’ cried she with an intensity of feeling which shook her delicate frame. ‘Spurn me not for this last weakness; this, Madhav, this, may be our last meeting; it must be so, and too, too deeply have I loved you—too deeply do I love you still, to part with you forever without a struggle.’

Did Madhav chide her? Ah, no! He covered his eyes with his palm and his palm became wet with tears. There was a deep silence for some moments, but their hearts beat loud. Matangini, recovering her presence of mind as speedily as she had lost it, first broke the heart-rending silence.

The distant and reserved demeanour, the air of dejection and broken-heartedness which had marked her from the first, had disappeared; the impetuosity and fervour of the first burst of a deep and burning love had subsided; and Matangini now stood calm and serene, her usually melancholy features beaming with the light of an unutterable feeling.

A sweet and sober pensiveness still mantled her tender features, but it was not the pensiveness of deep-felt enjoyment, for the wild current of passion had hurried her to that region where naught but the present was visible, and in which all knowledge of right and wrong is whirled and merged in the vortex of intense present felicity.

Was not Matangini now in Madhav’s presence? And had not her long-pent-up tears fallen on his hands? Had he not wept with her? That was all Matangini remembered, and for a moment the memory of duty, virtue, principle ceased to fling its sombre shadow on the brightness of the impure felicity in which her heart [revelled].

There was a fire in that voluptuous eye, —there was a glow on that moonbeam brow, and as she stood leaning with her well-rounded arm on the damask-covered back of the sofa, her beautiful head resting on the palm of her hand over which, as over the heaving bosom, stayed the luxuriant tresses of raven hue; —as thus she stood, Madhav might well have felt sure earth had not to show a more dazzling vision of female loveliness.

What a beautiful description of Matangini’s beauty as reflected through her demeanour and expression! But what is even more beautiful is the portrayal of her state of mind, her deep inner conflict — between passion and virtue, between love and family duty, between strength and weakness.

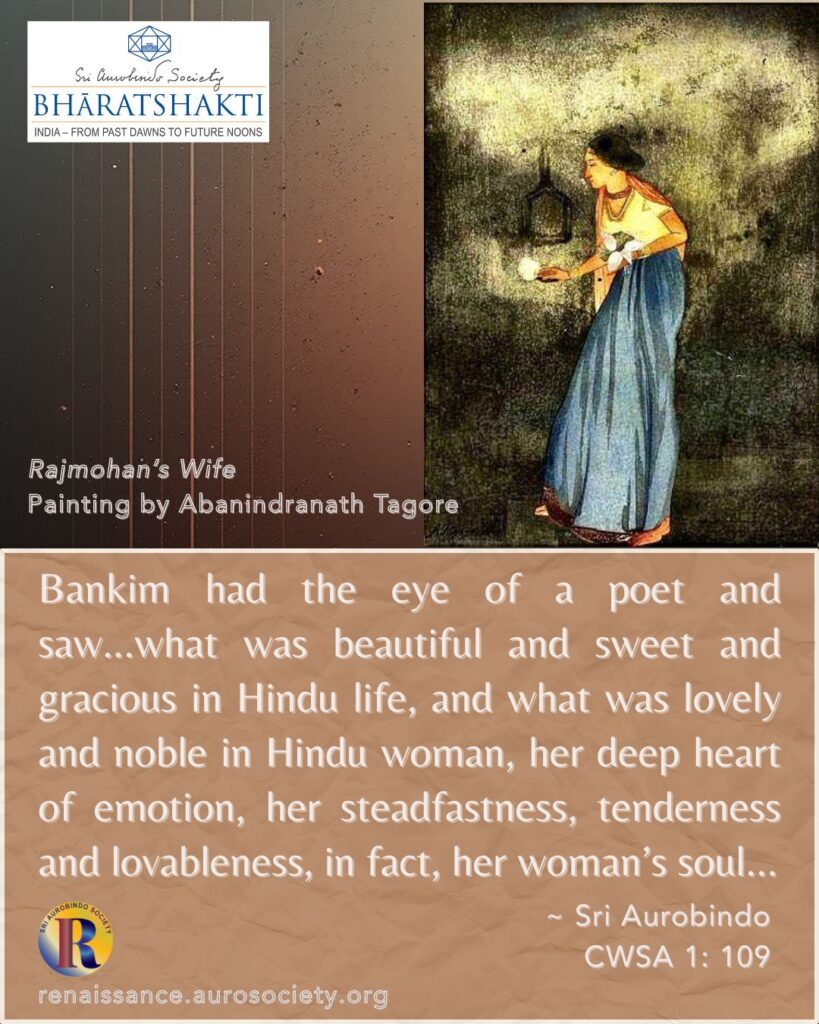

It was probably such descriptions — in this novel and in Bankim’s later Bangla novels — that perhaps made Sri Aurobindo write a wonderfully phrased comment on the portrayal of women in Bankim’s novels. Taking a humorous jab at the Anglicized social reformers of his time — sadly enough, many such ‘reformers’ exist till today among the circles of Westernized, urban, Indian intelligentsia who can’t find anything beautiful in Hindu ways of life and social organization —Sri Aurobindo wrote in his unique style:

“Insight into the secrets of feminine character, that is another notable concomitant of the best dramatic power, and that too Bankim possesses….The social reformer, gazing, of course, through that admirable pair of spectacles given to him by the Calcutta University, can find nothing excellent in Hindu life, except its cheapness, or in Hindu woman, except her subserviency. Beyond this he sees only its narrowness and her ignorance.

“But Bankim had the eye of a poet and saw much deeper than this. He saw what was beautiful and sweet and gracious in Hindu life, and what was lovely and noble in Hindu woman, her deep heart of emotion, her steadfastness, tenderness and lovableness, in fact, her woman’s soul; and all this we find burning in his pages and made diviner by the touch of a poet and an artist”.

Notes

- “… the language which a man speaks and which he has never learned, is the language of which he has the nearest sense and in which he expresses himself with the greatest fullness, subtlety and power. He may neglect, he may forget it, but he will always retain for it a hereditary aptitude, and it will always continue for him the language in which he has the safest chance of writing with originality and ease. To be original in an acquired tongue is hardly feasible. The mind, conscious of a secret disability with which it ought not to have handicapped itself, instinctively takes refuge in imitation, or else in bathos and the work turned out is ordinarily very mediocre stuff. It has something unnatural and spurious about it like speaking with a stone in the mouth or walking upon stilts. Bankim and Madhu Sudan, with their overflowing originality, must have very acutely felt the tameness of their English work. The one wrote no second English poem after the Captive Lady, the other no second English novel after Rajmohan’s Wife.” (Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, 1: 107) ↩︎

Continued in Part 2

~ Design: Beloo Mehra