Volume VII, Issue 1

Author: Beloo Mehra

Continued from Part 1

Allegory of Modern India?

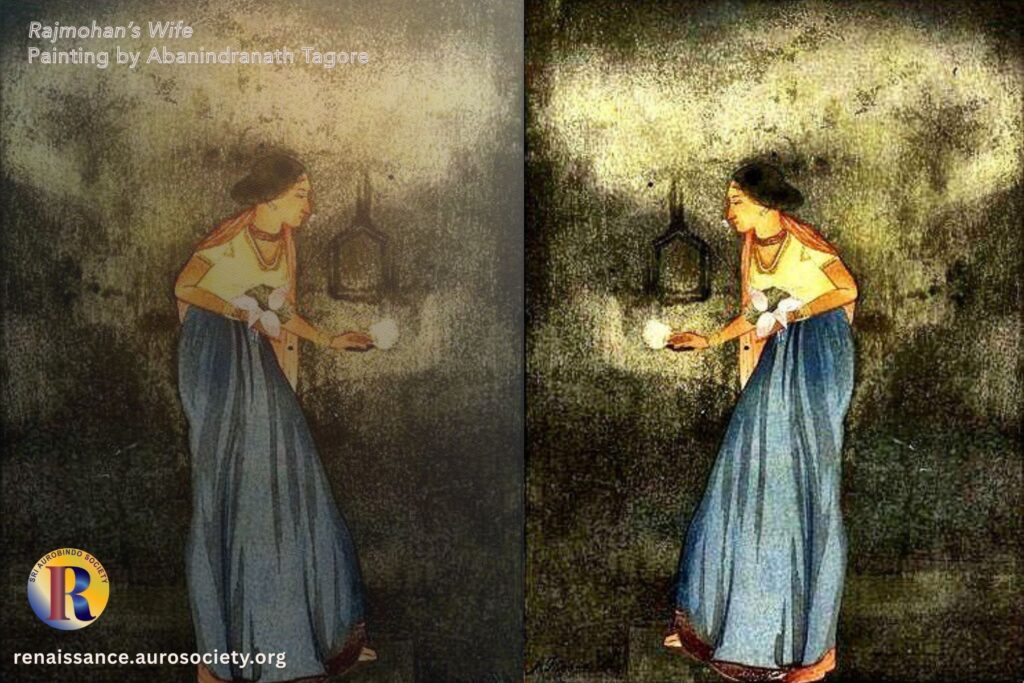

In a thought-provoking essay titled, “The Allegory of Rajmohan’s Wife: National Culture and Colonialism in Asia’s First English Novel”, Makarand Paranjpe presents his ‘allegorical’ reading into the characters of this novel, particularly Matangani. He remarks that in an alien tongue Bankim gives voice to a new India and an emerging Asia.

About Matangani, he writes that Asian fiction had not yet seen such a spirited and romantic heroine.

“Created from an amalgam of classical, medieval, and European sources and a totally unprecedented imaginative leap into what might constitute a new female subjectivity, Matangini is a memorable character. In all of Indian English fiction, there are few women who have her capacity to move the narrative. She, moreover, embodies the hopes of an entire society struggling for selfhood and dignity. Her courage, independence, and passion are not just personal traits, but those of a nation in the making. This subtle superimposition of the national upon the personal is Bankim’s gift to his Indian English heirs.”

Paranjpe argues that while the pronounced nationalism we find in his Anandamath comes later in Bankim’s literary career, its beginnings may be found in Rajmohan’s Wife. Through its “richly textured negotiation of cultural choices for a newly emergent society,” the novel is really an allegory of modern India, of the kind of society that can “rise out of the debris of an older, broken social order and of the new, albeit stunted, possibilities available to it under colonialism”. He continues:

“Rajmohan’s Wife gains in value and interest when we see it as a part of the story of modern India itself. This is a story that is still being written; in that sense it is a work in progress, which is exactly how I’d like to see Rajmohan’s Wife too.

“As a work in progress, rather than a false start, it negotiates one path for India’s future growth and development. In this path, the English-educated elites of the country must lead India out of bondage and exploitation. While the Rajmohans and Mathurs must be defeated, Matangini must find her happiness with her natural mate, Madhav.

“However, the latter is not possible just yet; Matangini has [to] therefore retreat to her paternal home. Like an idea ahead of its time, she must wait till she can gain what is her due. But not before she enjoys a brief but hard-earned rendezvous with her paramour and smoulders across the narrativescape of the novel with her disruptive power.

“Indeed, the novelty in Bankim’s novel is precisely the irruption, the explosion that Rajmohan’s wife—both the character and the story—causes in the narrative of modern India. Like a gash or a slash, the novel breaks the iterative horizons of a somnambulant subcontinent, leaving a teasing trace that later sprouts many new fictive offshoots.”

English-educated elites of the country leading India out of bondage and exploitation – is this still an idea ahead of its time? Bankim’s novel was published in 1864; is the idea relevant today in 2025? Has this path opened up the road for India’s growth and development?

These questions remain relevant to this day. The nature of bondage and exploitation may have changed from 1860s to 2020s, but the need for a freer and more equitable progress for all – on material, social, and cultural levels – remains important priority for India’s future evolution as a society and nation.

In some sense, these questions are even more significant today. We are presently not only witnessing a multi-faceted Indian resurgence but are also rethinking the very idea of ‘progress’ and re-assessing it in the light of culturally-rooted, Indic understandings of the idea of progress.

To address such questions, we need to look back, at least, at the past seven decades since India’s political independence. Has the English-educated elite that was created as a direct result of English education (which was more or less copied as the mainstream approach to education in Independent India) led the path of India’s progress and development and away from bondage and exploitation?

Answer to this is neither simple nor singular. A big part of the outer progress India has seen over the last 78 years can be attributed to the ingenuity, innovation and hard work of our English-educated elites. And in some ways, this elite has also been responsible for bringing a certain modernity in the Indian outlook toward social organisation, individual dignity and social freedom.

But in all likelihood, most of these shifts are primarily led by the demands of the external social and economic changes resulting from greater industrialisation and urbanisation, and not necessarily because of any sustained change in the deeper mentality. This very modernity has come to be seen as an imitation of something alien by many, particularly when the social-economic modernising project begins to enter into the cultural realm.

Indian social-economic-cultural consciousness continues to evolve, despite or perhaps because of, diverse push-and-pull mechanisms. A certain section of Indian society may feel a greater pull toward the ‘this is how India was in the past’ type of discourse and blame the ‘imported modernity’ for many of the present-day social concerns and problems.

On the other extreme, we still find a section that is quickly dismissive of all that was good and high in the past. They find nothing much of value in the indigenous social organisation framework which was informed by the timeless spiritual traditions. They champion for a complete break from the past by pushing India into a future entirely shaped by the Western rational-materialism.

Bankim’s Matangani, like the outer body of India (her social-economic-political realm) seems to have been caught up in this conflict. She belongs with Madhav, who at this point carries in him the seed of a truly modern outlook, thanks to his education, but isn’t ready to be with Matangani. Not just yet. Perhaps because he has not yet found the grounded-ness for his modernity to flower naturally in its context.

Madhav has not yet discovered the indigenous roots of his modernity. He is still running around looking elsewhere for a confirmation of his reason, his view on what is good for his future. And the future of his country. The Modern hasn’t been fully harmonised with the Eternal, the Reason hasn’t been fully integrated with the Faith, the progress of Mind hasn’t yet fully become the growth of Spirit.

Reading Bankim’s Rajmohan Wife in this light of what the novel’s characters may tell us about the nation and its future course of growth and development can be further enabled when we recall these words of Sri Aurobindo:

“I can only say that everything will have my full approval which helps to liberate and strengthen the life of the individual in the frame of a vigorous society and restore the freedom and energy which India had in her heroic times of greatness and expansion.

“Many of our present social forms were shaped, many of our customs originated, in a time of contraction and decline. They had their utility for self-defence and survival within narrow limits, but are a drag upon our progress in the present hour when we are called upon once again to enter upon a free and courageous self-adaptation and expansion…”

~ CWSA, 36: 274

Madhav in Rajmohan’s Wife isn’t perhaps ready yet to let go of all that drags his progress and that of his country. That’s why perhaps Matangani, an embodiment of the nation’s Shakti, is not really his at the moment. And when will Madhav be ready to be with Matangani? When will the English-educated elite of India find their grounded-ness in the Indian soul? That hope rests with the youth of India. To recall again from Sri Aurobindo:

“Our call is to young India. It is the young who must be the builders of the new world,—not those who accept the competitive individualism, the capitalism or the materialistic communism of the West as India’s future ideal, not those who are enslaved to old religious formulas and cannot believe in the acceptance and transformation of life by the spirit, but all who are free in mind and heart to accept a completer truth and labour for a greater ideal.

“They must be men who will dedicate themselves not to the past or the present but to the future…. It is with a confident trust in the spirit that inspires us that we take our place among the standard-bearers of the new humanity that is struggling to be born amidst the chaos of a world in dissolution, and of the future India, the greater India of the rebirth that is to rejuvenate the mighty outworn body of the ancient Mother.”

~ CWSA, 13: 511

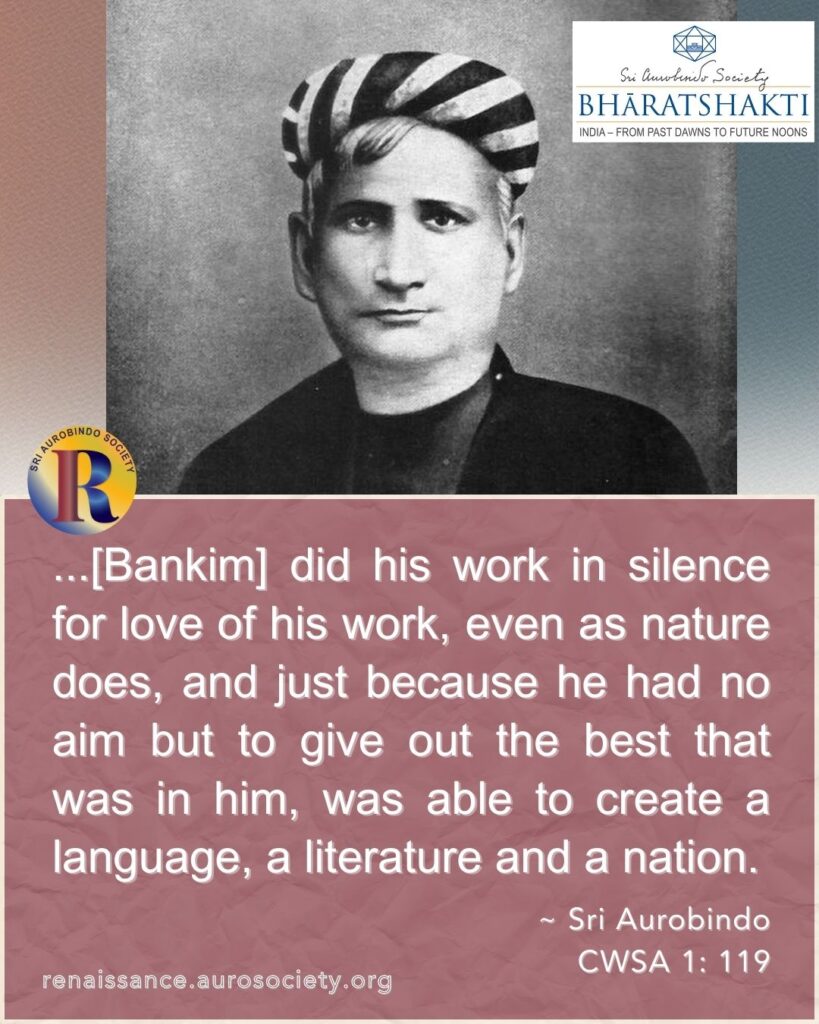

Rajmohan’s Wife, when read as an “allegory of modern India” reminds the reader that national consciousness when invoked through thoughtful and noble literature, art and music is always much more real and uplifting than anything uttered by political leaders and academicians. Sri Aurobindo’s words on the immense significance of Bankim’s literary work toward making of India are the most befitting means to conclude this essay.

“…when Posterity comes to crown with her praises the Makers of India, she will place her most splendid laurel not on the sweating temples of a place hunting politician nor on the narrow forehead of a noisy social reformer, but on the serene brow of that gracious Bengali who never clamoured for place or for power, but did his work in silence for love of his work, even as nature does, and just because he had no aim but to give out the best that was in him, was able to create a language, a literature and a nation.”

Read Part 1

~ Design: Beloo Mehra