Volume VII, Issue 1

Original Bengali writing by: Nolini Kanta Gupta

English translation by: Narendra Murty

Editor’s Note:

We feature an imagined conversation among three female characters from three of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s novels. Excerpted from the original Bengali writing of Nolini Kanta Gupta, it is available in his Complete Works in Bengali, Volume 3 (pp. 149-153) in the section titled, Mriter Kathopokathan, ‘Conversations of the Dead’. Narendra Murty has translated it into English.

The conversation presents an evolving view of a woman’s personal understanding of her rightful place and work in the context of family and the larger society and nation. What is her duty, her responsibility, her dharma? Towards her self, her husband and her home, her nation, and her inner truth? What is the ideal relation – if an ideal is possible – between a woman and a man in the conjugal context? Readers will find in this conversation a range of viewpoints which help explore these questions in their complexity and inherent diversity.

According to Sri Aurobindo, an individual “is not merely a social unit” (CWSA, 25: 24). Our societal role, work and function alone do not determine our individual existence, right and claim to live and grow. An individual is a soul within, a deeper being who must fulfil his or her own individual truth and law as well as his or her natural or assigned part in the truth and law of the collective existence.

But just “as the society has no right in suppressing the individual in its own interest, so also the individual, in Sri Aurobindo’s view, has no right to disregard the legitimate claims of society upon him in order to seek his own selfish aims” (Kishor Gandhi, Social Philosophy of Sri Aurobindo and the New Age, p. 67). Thus, it is important to understand the level of consciousness from which an individual’s ‘choice’ is arising.

Any call for ‘freedom of choice’ becomes, in the light of an integral spiritual perspective on human development, a much wider, higher and deeper movement of the human spirit – progressively evolving and expressing itself through physical-vital to rational to deeper subjective levels of consciousness. Also, this view does not leave out the truth of the larger collective life, starting from family to nation and beyond. Hence, choice does not remain merely an aggressively individualistic notion in this deeper view, but integrates within itself the necessity for a harmonious co-existence and interdependent growth of individual and the collective.

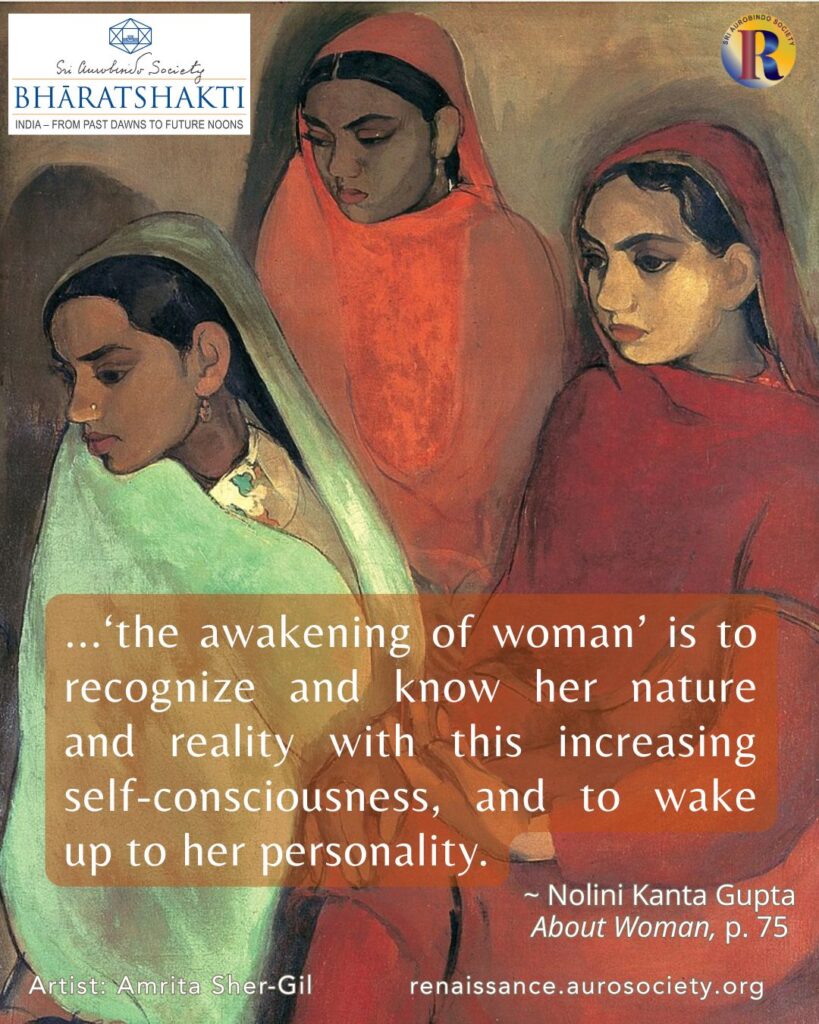

An awakened woman, one who is awakened to the shakti that she is in her essence, one who is awakened to the call of her inner progress and evolution, will feel more and more empowered as she begins to recognise within herself the working of the Four Great Powers – Wisdom, Courage, Harmony and Perfection – through which the Force of the Mahashakti, the Divine Mother, works and manifests in all. The corresponding Indian names of these Four Great Powers that Sri Aurobindo invokes in his powerful work titled The Mother are: Maheshwari, Mahakali, Mahalakshmi and Mahasaraswati.

This imagined conversation between Shanti, Suryamukhi and Kapalkundala magnificently illustrates many of these aspects. The small explanatory note by the translator will be helpful for those unfamiliar with these characters.

~ Beloo Mehra, Editor

More on Bankim’s Heroines in the Current Issue:

Woman and Nation in ‘Rajmohan’s Wife‘

Translator’s Note:

The participants in this conversation are three remarkable female characters from Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s novels: Shanti from Anandamath, Suryamukhi from Vishvriksha (The Poison Tree) and Kapalkundala from Bankim’s novel bearing the same name.

Shanti is a physically strong and patriotic woman who disguises as a man and joins a revolutionary band of Sannyasins after her husband, Jiban, leaves her to fight for the cause, driven by her intense love for him and her desire to be a hero’s wife. Suryamukhi is a devoted wife who embodies the ideal of a traditional, self-sacrificing Hindu wife in 19th-century Bengal. Her character is crucial to the novel’s exploration of themes like loyalty, polygamy, and the position of women and widows in society.

Kapalkundala is a young woman raised by a Tantric adept in the forest away from the influence of civilized life. She falls in love with a young man named Nabakumar who finds himself lost in the forest. She marries him but their love story is marred by danger, reappearance of a former estranged wife of Nabakumar who lays a fresh claim on him. The novel has a tragic ending as Kapalkundala, an innocent child of Nature, is unable to adjust to human society and the city life.

As a translator I found it very interesting that in the individual characters of the three women, Nolini Kanta Gupta discerned three separate temperaments that point to the three paths of Jnana, Bhakti and Karma Yoga. In her final concluding remark, Shanti, the heroine of Anandamath, gives voice to this line of thinking.

Shanti – Suryamukhi – Kapalkundala

Shanti: It has been long since the end of my earthly sojourn sister. The attraction for the earth is now just a faded memory. Then why this awakening? Is the time ripe again? Is it the call of duty once again? Has the time come for the fulfilment of my tapasya? In the life of work; to be a companion again in the Dharmakshetra, do I have to don the mantle of a warrior again?

Suryamukhi: I don’t know sister. I have no idea what my work is; nor have I cared to know where my strength lies. But in death as in life I shall remain at the feet of my lord and shall follow him always. Whether on earth, heaven or hell – I shall remain his shadow. This is the dharma of a woman; the karma of a woman. What more can be the desire, expectation, happiness or good fortune for a woman? I do not care where my husband is. I just want to render my seva to him by pouring all my love at his feet.

Shanti: You are right, sister. You would render seva to your husband and keep him nourished with your love – that is indeed the ideal for a woman. But I say that an ideal woman is one knows what is the true seva and where lies its true fulfilment? The seva at the level of the physical body is an inferior giving. The vital love falls in the middle category. But the highest offering is that of soul-force; the power of tapasya.

Don’t you know my sister why the other name for a woman is Shakti? In the pursuit of the goal of life, we are the companions, fellow sadhikas. If we do not render our strength to man, he would lose even the strength he possesses on his own. On what is founded the power of Shiva? On the strength of Gauri’s tapasya!

Suryamukhi: I don’t know about the gods, but we are human beings. For us, the place of a woman is always in the home. The outside world of the battlefield of life, the noise of the fight and struggle for survival is meant for the man. Why should a woman imitating a man jump into this battlefield of life?

Every man needs a serene haven, an abode of peace away from the din of life. A woman’s job is to build the peaceful home where the tired man can rest and find comfort. To make that shelter inviting and rejuvenating for him. The impulse of the man is to seek and run in the outside world, to break free from all bonds seeking freedom – but it is a woman’s job to throw around him a protective net of love and affection with the passion of her heart so that he remains grounded and never loses his own self.

The woman’s strength is not in the running in the outside world along with him but to keep draw him inwards into his soul. A woman is a man’s ardhangini – but it is in the inner half of a man where lies her duty and rightful place.

Shanti: It is true that a woman is a man’s ardhangini, Suryamukhi. But a bigger truth is that a woman is also a man’s saha-dharmini. While at home, a woman is a man’s griha-lakshmi. But in the field of work, a woman is a man’s brave companion, a fellow worker. This is the greatness of a woman.

Not only do we have to give happiness to our man, but also our strength. Why should we abandon him to fend for himself in the field of work? There too we should strengthen and protect him with our heart, mind and body. If we remain aloof from his work in the world, won’t we remain forever cut-off from a half of his life?

Suryamukhi: But don’t you know that true womanhood lies in motherhood? Motherhood is the great responsibility of every woman. Just as a man has no role to play in this great responsibility of motherhood, similarly a woman’s interference in a man’s world is not necessary. If a woman gets involved in a man’s world, then her womanhood would definitely be affected. Raising the child, the future man, is the immense responsibility and the justification and fulfilment of a woman’s life.

Shanti: The duty towards the child is the responsibility of both the man and the woman. That is a partial reality of the relationship between a man and a woman, not the whole reality.

Kapalkundala: I am finding the views of both of you quite incomprehensible. I am not able to make any head or tail of this man-woman relationship as being expressed by you. Why are you both so hell bent on tying the man and woman together? Man is independent. So is a woman. Why do they need to become a half of each other – “ardhangini” as you call it? Why? For what purpose?

Shanti: Kapalkundala, you are a woman who was raised in the wilderness. You have no understanding of the norms of the society. Man is a social animal. And the man-woman relationship is the foundation of a society. When God created humanity, society was born too. Thereafter, man and woman got together and created multiple centres of domestic life thereby building the edifice of human society.

Suryamukhi: A woman who has never tasted the fruit of family life, her human birth is futile. She could neither know and discover herself, nor could she know and discover the other. The mystery of man-woman, husband-wife relationship is not a thing than can be understood by the head, sister.

Kapalkundala: Is your society and married life really so pleasant, so beautiful? Whatever experience I had of it, it still weighs like a nightmare in my mind. Society! Married life! What a terrible prison it is! Domestic ties? That’s nothing but bondage. Freedom, independence, unrestricted movement – is there anything more pleasurable, more comforting than these? Oh! Is there any torment greater than the torment of love? Uniting one’s life with a man’s life – what an impossibly difficult life of demands and duties it is! No wonder I gave it up because I couldn’t tolerate it.

Shanti: Yes, these demands and duties is what life is all about. You are unfortunate that your life could not bloom to its fullest capacity. In the torment of these demands and duties lies the uniqueness of man, the fulfilment of his life. Standing in the midst of the interaction between the two, man becomes eligible for a greater life; acquires an identity that is bigger than his own narrow individuality. He attains to a fuller and complete life.

Kapalkundala: What you people are calling fullness and fulfilment of life, I call it bondage. Man could find the fulfilment of life in other ways too; could build society on a different plan. Man is a human being – whether a man or a woman. Every human being has his own path, his own work and his own dharma. To be inspired by the freedom of his own inner soul, moving ahead in his joy and inner abundance – therein lies his true fulfilment. Why should he tie his life with another and lose his own selfhood in the process?

I feel that because man is living in this manner that society is not progressing; it is suffering from disharmony and an inner poverty. Staying in this kind of a society, man has lost the inner freedom of his soul. That is why I find in all ages and in every society, the truly great ones did not succumb to this self-immolation; they abandoned the society and became monks and renouncers.

Suryamukhi: Because they did not have the fortitude and capacity to carry out their duties. What men and women have followed in every age and in every society continuing an unbroken tradition; that which has enriched life and made it fruitful is supposed to be a worthless exercise? And a few outcastes like you who have not tasted the fruit of societal life – they are supposed to be adherents of a true life? Those who have lived outside the margins of society, have been regarded as selfish and self-centred. They thought that they could avoid society in this manner. But ultimately, they were the ones who indulged in self-deception.

Shanti: No, I won’t go that far. What they followed was an ideal which had to be pursued outside the borders of society. But the road to that renunciation was through the heart of society itself. Though I personally see nothing wrong in it, I also do not believe that it is absolutely essential. Each path has its own rewards.

Kapalkundala: Bondage is something that I had always shunned. Let a man stand up independently on his own strength and inner sovereignty. There is nothing greater than one’s own inner soul and inner divinity. I demand freedom, independence and feminine sovereignty.

Suryamukhi: Only when a man’s inner soul is united with another does it become whole. Otherwise, it is fragmented. Not choosing to be libertines. Because only when two halves meet and fuse into one, do they become truly free. And it is the woman who leads the way – with her self-sacrifice and love. For in love lies a woman’s freedom and joy.

Shanti: A woman is Shakti – the power of Tapas. Kapalkundala, you are probably indicating the path of Knowledge – Jnana; and Suryamukhi, you are showing the greatness of the path of Love and devotion. But I consider power – Shakti and work in the world a woman’s real strength.

From Renaissance Archives:

Equality, Freedom, and Education: A Look at the Book ‘About Woman’

~ Design: Beloo Mehra