Volume II, Issue 2

Author: Beloo Mehra

Part 1

The Guru-shishya parampara, which has been an important part of the millennia-strong and continuously living, growing and expanding Indian cultural tradition is often misunderstood and even disparaged by many modern-educated-urban-westernized-Indians. The reason is often their complete ignorance or mental prejudice, or both. The only way to cut the prison of ignorance is with knowledge, especially knowledge gleaned from the great spiritual masters from this land of Bhārata.

In this two-part article I share a few selected insights from Sri Aurobindo on the guru-shishya parampara. In many of Sri Aurobindo’s writings, especially in thousands of letters written to his disciples and devotees (published under the 4-volume set titled Letters on Yoga), we find a great deal on what he once called as Guruvada.

Here I focus only on a few specific topics as I highlight Sri Aurobindo’s deep insight and wisdom on why one needs a Guru, the true role or work of a Guru, the ideal relation between a Guru and a disciple, and why the tradition itself results in a diversity of teachings, paths and gurus.

Let me begin by quoting from the Master, who has been spoken of as “a reluctant guru.” In a letter dated 16 January 1936, he said that not unlike many modern minds he once had the same kind of violent objection to “Gurugiri, but you see I was obliged by the irony of things or rather by the inexorable truth behind them to become a Guru and preach the Guruvada.” (CWSA, Vol. 35, p. 398).

He explains that wrong objections to the tradition of Guruvada happen when modern mind in its ignorance and arrogance tends to make a rigid formula and dry shell of all things spiritual and divine, including the guru-shishya parampara. So while the “violent objections” to guru-shishya parampara that are raised today by sections of English-educated modernised Indian elite may be understandable on some rational level, it is important to challenge and cut through them by the true knowledge of the truth behind this timeless tradition.

Again, to quote from Sri Aurobindo:

Up to now no liberated man has objected to the Guruvada; it is usually only people who live in the mind or vital and have the pride of the mind or the arrogance of the vital that find it below their dignity to recognise a Guru.

(CWSA, Vol. 29, p. 192)

Why Do We Need a Guru?

In The Synthesis of Yoga, Sri Aurobindo says that combined working of the four great instruments are essential for any spiritual attainment by a sincere seeker on the path of Yoga.

There is, first, the knowledge of the truths, principles, powers and processes that govern the realisation— śāstra. Next comes a patient and persistent action on the lines laid down by this knowledge, the force of our personal effort— utsāha.

There intervenes, third, uplifting our knowledge and effort into the domain of spiritual experience, the direct suggestion, example and influence of the Teacher— guru. Last comes the instrumentality of Time—kāla; for in all things there is a cycle of their action and a period of the divine movement.

(CWSA, Vol. 23, p. 53)

Sri Aurobindo deals extensively with the deeper and inner truths behind all these great “four aids.” For our present purposes, let us go straight to what he says about the significance of the Teacher, the Guru for a sincere seeker.

While in the absolute final analysis it is the Divine Guide within the seeker who is his or her ultimate Guru, but it is extremely difficult, almost impossible for the egoistic consciousness to even get in touch with this inner Divine Guide. This is especially true for the beginners on the path.

And, if done at all, it is still difficult to do it perfectly and in every strand of our nature. It is difficult at first because our egoistic habits of thought, of sensation, of feeling block up the avenues by which we can arrive at the perception that is needed. It is difficult afterwards because the faith, the surrender, the courage requisite in this path are not easy to the ego-clouded soul.

(ibid, pp. 63-64).

With his perfect insight into the highest and deepest psychology of human nature, Sri Aurobindo continues further –

But while it is difficult for man to believe in something unseen within himself, it is easy for him to believe in something which he can image as extraneous to himself. The spiritual progress of most human beings demands an extraneous support, an object of faith outside us.

It needs an external image of God; or it needs a human representative,—Incarnation, Prophet or Guru; or it demands both and receives them. For according to the need of the human soul the Divine manifests himself as deity, as human divine or in simple humanity—using that thick disguise, which so successfully conceals the Godhead, for a means of transmission of his guidance.

(ibid, p. 64)

For various reasons, but perhaps mostly because of the exclusively-rationalistic-materialistic modernity, it has now become almost a fashion for a large section of culturally uprooted Indians to completely reject this need of extraneous support. Sadly, we see this even among people who claim to be ‘seekers’ and ‘spiritually-inclined’. Haven’t we all heard things like – “oh no, I don’t need this or that Guru, or this or that Deity to be spiritual; all that is for the ignorant masses who only know how to mindlessly follow someone’s teaching; I am highly rational and critical, so I can’t simply unquestioningly follow anyone’s advice, I follow my own spiritual process, etc. etc…”?

While such an attitude may be a sign of an ego-clouded consciousness or simply a blatant arrogance of the mind or outright rejection of the tradition, it is important to remember that this can also be a dangerous path for a true seeker especially in the early stages.

From times immemorial Indian spiritual tradition carried forward by innumerable rishis, yogis and munis has plunged into the deepest depths of human nature and has climbed the highest ranges of human consciousness, and has come up with a rich corpus of well-founded disciplines to guide a sincere aspirant who has heard the call of the Spirit.

While different disciplines or paths address the inherent diversity of human nature and temperament, at their core they all provide for the deepest need of the human soul.

That is the need to develop and build faith, which is the first step to spiritual seeking – faith in something beyond the material reality, faith that higher ranges of consciousness exist above and beyond the ordinary physical-vital-mental realms in which we are stuck almost every second of our day, faith that these higher levels of consciousness are attainable or at least can be experienced for a few moments, faith that such an experience is possible if one sincerely aspires.

“The Hindu discipline of spirituality provides for this need of the soul by the conceptions of the Ishta Devata, the Avatar and the Guru.”

(ibid, p. 65)

In his characteristic patient and thorough style, the Master goes on to explain the deeper need for the conceptions of Ishta Devata and Avatar. While for some, a chosen deity, ishta devata, who is a name and form of the transcendent and universal Godhead, is the means to connect with the Divine, others feel a necessity for a human intermediary so that they may feel the Divine in something entirely close to their own humanity.

This need for an influence and example is satisfied by the Divine manifest in a human appearance, the Incarnation, the Avatar.

Sri Aurobindo then goes on to add that those who cannot conceive or are unwilling to accept the Divine Man, they may however be ready to open themselves to the supreme man, terming him not incarnation but world-teacher or divine representative. But for many still, “a living influence, a living example, a present instruction is needed.” He explains:

For it is only the few who can make the past Teacher and his teaching, the past Incarnation and his example and influence a living force in their lives. For this need also the Hindu discipline provides in the relation of the Guru and the disciple.

The Guru may sometimes be the Incarnation or World-Teacher; but it is sufficient that he should represent to the disciple the divine wisdom, convey to him something of the divine ideal or make him feel the realised relation of the human soul with the Eternal.

(ibid, pp. 65-66)

Sri Aurobindo adds that a sincere sadhak is free to make use of all these extraneous supports according to his or her inner nature.

But it is equally important for the sadhak to shun the limitations of these supports and “cast from himself that exclusive tendency of egoistic mind which cries, “My God, my Incarnation, my Prophet, my Guru,” and opposes it to all other realisation in a sectarian or a fanatical spirit. All sectarianism, all fanaticism must be shunned; for it is inconsistent with the integrity of the divine realisation.” (p. 66).

The Work of the Guru

A Guru’s work is essentially to awaken the Divine Guide within the disciple. To this end, a guru leads the disciple through the nature of the disciple, using three key instruments – teaching, example, and influence.

A wise guru or teacher does not impose himself or his opinions on the passive acceptance of the disciple’s receptive mind; he sows as a seed only what is productive and sure, a seed which will grow under the divine fostering within. A guru awakens much more than instructs; he aims at the growth of the inner faculties and the experiences by a natural process and free expansion.

A guru offers the disciple some particular method of sadhana as an aid, as a device to be utilised, but not as an imperative formula or a fixed routine. And he must be careful not to turn any of the means or methods into a mechanical process or a limitation. A guru’s whole business “is to awaken the divine light and set working the divine force of which he himself is only a means and an aid, a body or a channel.” (ibid, p. 67)

***

More powerful than the instruction is the guru’s example. However, it is not the example of the outward acts nor that of the personal character which is most significant. As Sri Aurobindo explains, these things have their place and their utility; but what most kindles aspiration in others is the central fact of the divine realisation within the guru, the realisation which governs his whole life and inner state and all his activities.

This is the universal and essential element; the rest belongs to individual person and circumstance. It is this dynamic realisation that the sadhaka must feel and reproduce in himself according to his own nature; he need not strive after an imitation from outside which may well be sterilising rather than productive of right and natural fruits.

(ibid, p. 67)

But according to Sri Aurobindo, influence of the guru is even more important than example.

Influence is not the outward authority of the Teacher over his disciple, but the power of his contact, of his presence, of the nearness of his soul to the soul of another, infusing into it, even though in silence, that which he himself is and possesses.

This is the supreme sign of the Master. For the greatest Master is much less a Teacher than a Presence pouring the divine consciousness and its constituting light and power and purity and bliss into all who are receptive around him.

(ibid, p. 67)

Sri Aurobindo is also very clear and precise when he describes who is a true guru. A true guru or spiritual master does not arrogate to himself Guruhood in a humanly vain and self-exalting spirit.

His work, if he has one, is a trust from above, he himself a channel, a vessel or a representative. He is a man helping his brothers, a child leading children, a Light kindling other lights, an awakened Soul awakening souls, at highest a Power or Presence of the Divine calling to him other powers of the Divine.

(ibid, pp. 67-68)

CONTINUED IN PART 2…

Editorial Note: An earlier version of this article was published HERE.

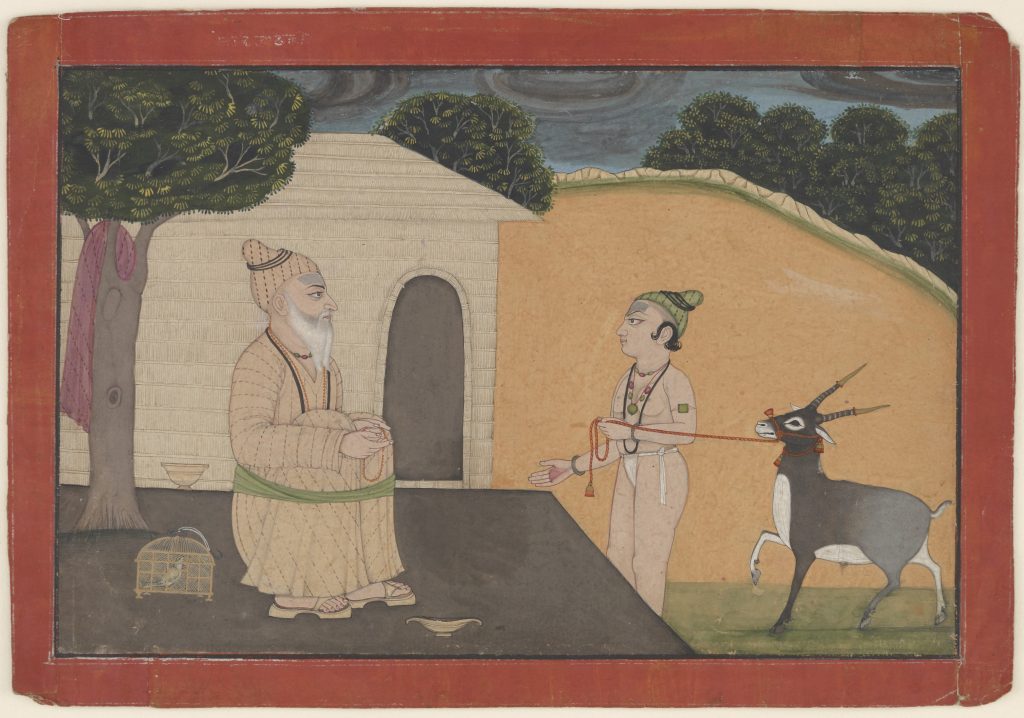

~ Cover image: Painting by Priti Ghosh