Volume 1, Issue 4

Author: Beloo Mehra

Editor’s Note: This book by Bharat Gupt presents a novel way of understanding contemporary Indian society and its challenges by applying an Indian sociological framework. Selected excerpts from the book are presented along with a brief review.

In a letter sent to his brother in 1920, Sri Aurobindo wrote:

“I believe that the main cause of India’s weakness is not subjection, nor poverty, nor a lack of spirituality or Dharma, but a diminution of thought-power, the spread of ignorance in the motherland of Knowledge. Everywhere I see an inability or unwillingness to think – incapacity of thought or “thought-phobia.””

The book that we have chosen to highlight this month in our ‘Book of the Month’ series compels us to see the truth of this statement as it still holds today. But more importantly, it compels us to give up this “inability or unwillingness to think” and this “incapacity of thought.” It provokes, rather compels us to think, and think hard.

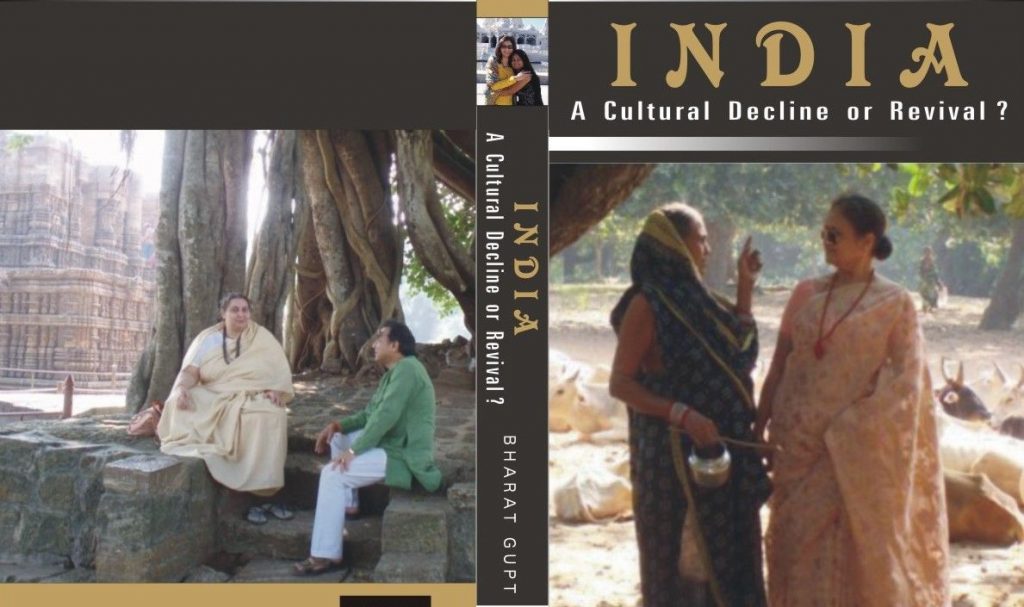

Prof. Bharat Gupt who is currently a member of Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts, is a retired Professor of English from Delhi University. He is an Indian classicist, theatre theorist, sitar and surbahar player, musicologist, and a cultural analyst and commentator. For many years he wrote articles in several newspapers on issues concerning Indian culture, society and polity, many of which became the basis of his 2008 book titled “India – A Cultural Decline or Revival?”

About the Book

Title: India – A Cultural Decline or Revival?

Author: Bharat Gupt

Publisher: D.K. Printworld (Dec. 1, 2008)

ISBN-13: 978-8124604595

The book provokes us to re-assess and re-think the categories in which we have been accustomed to speak, unintelligently and unquestioningly, of matters concerning Indian society and culture. We have been doing so because we don’t know otherwise. We don’t know because we haven’t been taught in our schools and colleges to think and observe like an Indian.

In that sense the book is about Indian education, particularly the socio-political culture that has shaped Indian education since independence, and the ways in which this culture of ignorance, this culture of ‘self-unawareness’ has led us to completely misunderstand and misrepresent India, Indian culture and values to ourselves and the world.

The book makes us think why it is important to understand the Indian society and culture from the perspective of an Indian world-view, an intellectual framework that is rooted in the Indian cultural thought and way of being.

The title of the book in itself compels us to think – is Indian culture going through a phase of decline or a revival? While at this point, we need not go into the term ‘revival’ itself – what it means or rather what it doesn’t mean – we must focus on the question itself, more importantly, we must focus on the answer to this question.

The answer, as the book seems to indirectly suggest, is to be discovered by each one of us.

But at the same time there are some clear lines of inquiry given by the author which will help us start our own culturally grounded inquiry. The prerequisite, however, is that we first take the trouble to learn the essentials of a ‘culturally grounded’ framework which will help us observe, understand and know the Indian society and culture in a new light, and not merely from a West-centric intellectual ‘ethnographic’ perspective.

The book’s Table of Contents itself gives us the fundamentals of the framework or the lines of inquiry to be followed.

Divided into six sections: Eka, Kula, Grama, Janapada, Prithvi and Aatman, the book presents a powerful critique of contemporary Indian society as well as the policies adopted by the Indian State after India’s independence from the British colonial rule. Prof. Gupt not only offers a lucid analysis of selected topics in each of the six sections, but also presents a practical way forward out of many challenges which continue to plague the Indian society and impede an authentic renaissance of Indian culture.

Why These Six Sections?

The author takes inspiration from a shloka that appears in Mahabharata, Panchatantra and several other texts. This shloka, the author argues, offers a “neeti or practical ethics for organising a humane social order that provides as much for the single person as for its larger units.” (p. xiv)

त्यजेदेकं कुलस्यार्थे ग्रामस्यार्थे कुलं त्यजेत् ।

ग्रामं जनपदस्यार्थे ह्यात्मार्थे पृथिवीं त्यजेत् ॥

tyajedekaṃ kulasyārthe grāmasyārthe kulaṃ tyajet ।

grāmaṃ janapadasyārthe hyātmārthe pṛthivīṃ tyajet ॥

Give up the individual for the family, the family for the habitat, the habitat for land. But for the ātman, give up the whole earth.

(Translated by the author)

Let us hear how Prof. Gupt explains it as an appropriate framework for his inquiry as well as inquiry all of us must undertake if we wish to seek an answer to the question – what will help the Indian cultural revival and how can I as an individual contribute?

The Eka, Kula, Graama, Janapada, Prithvee and Aatman make up the mental and terrestrial shells for the inner and outer being of an individual in Indian terms. The changes that have taken place in these areas can index the decline or revival in cultural life.

Eka is the individual, male or female, that makes up the unit of cultural consciousness and the fulcrum of creative ability. If the Eka breaks either due to a hostile social environment or due to lack of inner ethical strength, the social order that depends upon individuals will also collapse.But so it shall also if the individual is unable to give up one’s selfish interest for the larger unit of Kula (family), the family for Graama (habitat), the Graama for Janapada (regional kingdom/political unit/nation), and the Janapada for Prithvee (earth) and all material interests of the earth for the Aatman (Self).

The mode of this non selfish action varies with time and place but as a principle for action it is none other than what Socrates called the Supreme God (ton agathon) and what the Indian philosophers have called dharma.

(pp. xiv-xv)

The author goes on to say that he has chosen these terms because they not only define the Indian cultural experience more accurately than the Western categories such as the ‘individual’, ‘society’, ‘nation’ and the ‘global order,’ but also represent the inner nature of the relationship that exists among the various layers of one’s existence. The “humane social order” that the earlier-mentioned shloka speaks of does not suggest a denial of any interest – it is rather a classification of references as to which layer of existence can claim a greater attention.

This social order represents the essential nature of the polity that Indian dharmashastras and arthashastras speak about.

This is the Indian sociology that must be the framework for understanding our society and culture. Such a framework need not exclude any discussion of the class struggle, ethnic divisions and other issues which the modern Western sociology is so obsessed about, but those are the not the parameters by which the real nature, structure, and challenges of Indian society can be studied. In this way, the book also presents a model for modern Indian sociology.

Some Glimpses from the Book

Shared below are a few excerpts from this highly thought-provoking book to highlight some of the themes explored by the author. One of the criteria used to select these excerpts is that these directly speak to the themes of education, culturally rooted individual identity, and the deeper cultural idea of Indian nationhood – the themes we have been exploring in Renaissance so far.

It must be said that the brief selection shared here does not do justice to the eloquent analysis done by Prof. Gupt, but may still whet the reader’s appetite to pick up the book and read it in its entirety.

On the Ancient Individualism and the Indian Artist

In the Indian, or rather in the Asian tradition, the trained (samskrita) or the educated individual has been the cornerstone of creativity, and hence of action and leadership. The notion of rustic simplicity, or lack of training as a mark of purity and naturalness, of the “mute inglorious Milton” is a Euro-Romantic concoction.

In India, “graamya” (crude) or “praakrta” (natural) was regarded as impure, being untrained. However, the very notion of individualistic creativity in the whole of the ancient world was different from modern Euro-Romantic or post-modernist ideas of a shopper-like free floating self.

Ancient individualism was rooted in community obligations and was meant to enlarge itself towards bigger entities….

Such giving up of “the whole earth” for the “self” really ends up in the self belonging to the whole earth, so different from the modern globalist-consumerist egocentrism. Also, the ancient “self”-seeker was not always the moksha seeking wanderer, or the renouncer; he could also be a break-earning family man, rooted in a village or city.

He/she could be a creative “self”-seeker, pursuing any of the 64 kalas, the arts, and could regard his pursuit as his liberation. After all, this has been the proclaimed faith of the Indian artist through the ages.

(pp. 19-20)

On Arts Education

A concerted effort needs to be made to reinstate the arts as a creative, therapeutic and moral force in our educational system, print and electronic media. In schools the arts should be among the main subjects of study and not mere extracurricular activities. Five to six years of regular theatre classes in native language can develop clear speech, health and graceful carriage, and a direct familiarity with literature, myth and poetry in an easy way.

It is more gracious and delightful than the present system of cramming through print. It has been demonstrated that theatre, dance, painting and music are the best instruments of personality development for children. Why can there be no marking, promotion and academic recognition for them? Why have they been relegated to the lower category of ‘vocational subjects’ meant to be taken by duller kids?

When will we stop thinking of art as a handmaid of business, diplomacy, or infotainment and recognize it as an elevating experience that distinguishes humans from animals?”

(p. 24)

Politics in College Campuses

There has been no evaluation at national level if the decision to reduce the voting age to 18 has been really helpful either to the political parties or democracy as a whole…

On the contrary, the ill effects of lowering the age to 18 are well known. Any college teacher will tell you that political parties have intensified their activities on campuses and further vitiated the academic atmosphere.

The criminalisation of higher education has multiplied many fold…Instead of involving the young in the political process as opinion makers, it has alienated them from political activity which is totally monopolised by the criminal-political nexus. Those who remain politically active are divided along party lines.

(p. 114)

“Is India a Senile Culture?”

When those who should have retired continue to wield power, the nation comes to live under the shadow of senility. We witness this in every sphere of our national life.

Our artists, thinkers and scientists are repetitive, or at best Euro-intimidated; by and large, universities and schools have not restructured courses and their contents for half a century; the bureaucratic system has stayed perfectly colonial; religious, parochial and linguistic enclosures have tightened; caste barriers have been reaffirmed; caste endogamy is flourishing; every political party in India has arrived at an ideological dead-end as they have little more to offer than a tokenist jargon…

(pp. 72-73)

On the Role of Rightly Conducted Rituals in Making an Individual Identity

…the best way to declare one’s Indian modernity is still to condemn ritual as deceit. This censure pervades not only the speeches of chest thumping social reformers, writers, poets, academics and journalists but just about anybody who is anxious to be called a citizen of his times…But the most amusing thing about these progressives is, that whole they condemn the rituals of religion, they celebrate the rituals of the secular State like parades, prizes, ceremonies and celebrity parties with untiring addiction….

Besides reinstating the myth that rituals are empty, the ‘scientifically tempered’ also allege that rituals are mechanical repetitions. Rituals seem so to the uninitiated and the unobservant. The rightly conducted ritual brings about a change in the doer’s mental state, which is predictable, well tried, and permanent and not merely an autosuggestion or a hallucination.

Controlling the mind in the entirety of its thoughts and feelings has been demonstrated and regularly applied in India in various fields like the arts, interpersonal relationships, social work, and spiritual pursuits. Throughout history, remarkable feats of character change and elevation have been achieved across the globe by the transformation wrought in individuals through ritual….

It seems that in the 21st century, for a variety of reasons, the individual will find itself more and more cut off and lonely from the State, the family and the community as these units are becoming more an end to themselves and are doing less and less to nurture the individual.

One of the ways the individual can nourish or renew one’s strength is to choose one’s personal rituals to transform the inner self for survival…Rituals can be of diverse kinds, from the very mundane sort like feasting to the perfection of an art form, to an intense dedication to the spiritual. A conglomeration of happier individuals is a happier and more peaceful world.

(pp. 7-11)

“Sacredness of the Land as a Social Unifier”

The holy sites like Rameswaram, Dwaraka, Kashi, Gaya or Pavapuri, thousands of miles away, have commanded since very early times and still command the same sense of belonging in an Indian as his or her place of settlement (graama), or origin (moola).

The Indian obligation to travel to holy sites, or encourage and assist the travellers to these places, is much stronger than seen in other cultures. No wonder that with every passing occasion miraculous numbers gather at Kumbha and other pilgrimages.

This sacred belonging of the Indian to the land as a whole cannot be underestimated even though it is beyond the grasp of modern secular notions of citizenship and state.

Political scientists working under Western paradigms cannot count upon sacredness of the land as a social unifier just as the conquering Europeans could not understand why the American Indians could not sell their land because they considered it sacred.

This sacred bonding with whole of India cannot be dismissed as a phenomenon of the past as it is still a major driving force in the lives of Indian people who, including the poorest, overstrain their means and health to make these journeys.

Most unfortunately, Nehruvian secularism failed to nurture pilgrimages and pilgrims and thus weakened national bonding and cultural flowering. Devaluation of religion as an article of political faith continues to dear India from using its inherited infrastructure of emotional growth, unity and richness.

(pp. 144-145)

On Cultural Consonance

If communication is to be something more than exchange of goods or info-commodity, then we may benefit most from turning to an old definition of communication called ‘samvada’…The samvada theory rests upon the postulation that differences rest or stand or common ground.

Differences cannot exist all by themselves. In other words, the One creates the many, the Scale creates the notes. Identities are meaningful only so long as they interact, as do the musical notes in relation to one another. Cultures are vibrant only when they reveal their consonances.

Otherwise, they stagnate or become violent, leading both ways to destruction. We need to have a fresh look at creating consonances, call for harmony, and oppose hegemony which has been our cultural purpose for so long.

(pp. 175-176)

A Few Last Words

While the above passages definitely give the readers a good peek into the rich analysis that the book offers, I must add that these hardly scratch the surface of the many layers that the book uncovers in its 230 pages.

Each of the points included above is contextualised in the book in two significant ways:

- one, by situating them in the cultural past of India which continues to exert its presence till today, despite many attempts by the champions of half-baked and culturally hollow ideas of a West-aping modernity and secularism;

- and two, by presenting them as data points from modern Indian history in which the modern Indian State since independence has not bothered about making any meaningful structural changes in the social-political systems in order to bring them closer to the spirit of Indian ethos and values, and instead tinkered only at surface level reforms, which are essentially driven more by short-term political gains, and which have more or less kept the State, the bureaucracy, the education and the idea of nationhood itself as deeply colonised and culturally uprooted.

The entire book is full of highly thought-provoking and rich insights.

The chapter titled ‘What is Ethnic?’ brings out some important points about the role of Euro-Western notion of ‘ethnos’ and its corresponding method of ethnography, in the colonial project as well as its continuing use to stir up sub-nationalisms in the non-European world by wrongly (or rather deliberately) fusing ethnic identity with national identity.

This chapter is an important read not only from a historical perspective to understand the contemporary Indian context but also as a lens to explore the origins of many of the inter-national and civilisational conflicts we see in the global sphere today.

A special mention must be made of the section on Aatman in which Prof. Gupt creatively uses the device of an ancient Greek dialogue to explore two questions – “Relativism: A Moral Twilight” and “Searching for the Sahaj.”

Like rest of the book, these too leave the reader much to reflect upon as the philosophers debate and uncover the finer points of dharma, aachara, morality, vanity, happiness, delight and many other things including the subtler distinctions between the Buddhist and Hindu ways of thinking about them.

On the whole, the book is a must-read for anyone interested in India – her past, present and future.