Volume VI, Issue 1

Author: Sri Aurobindo

Editor’s Note: In this part Sri Aurobindo helps us understand that in its inmost reality, a temple symbolizes spiritual aspiration. Its rich details and ornamentation represent the infinite multiplicity in Infinite Oneness.

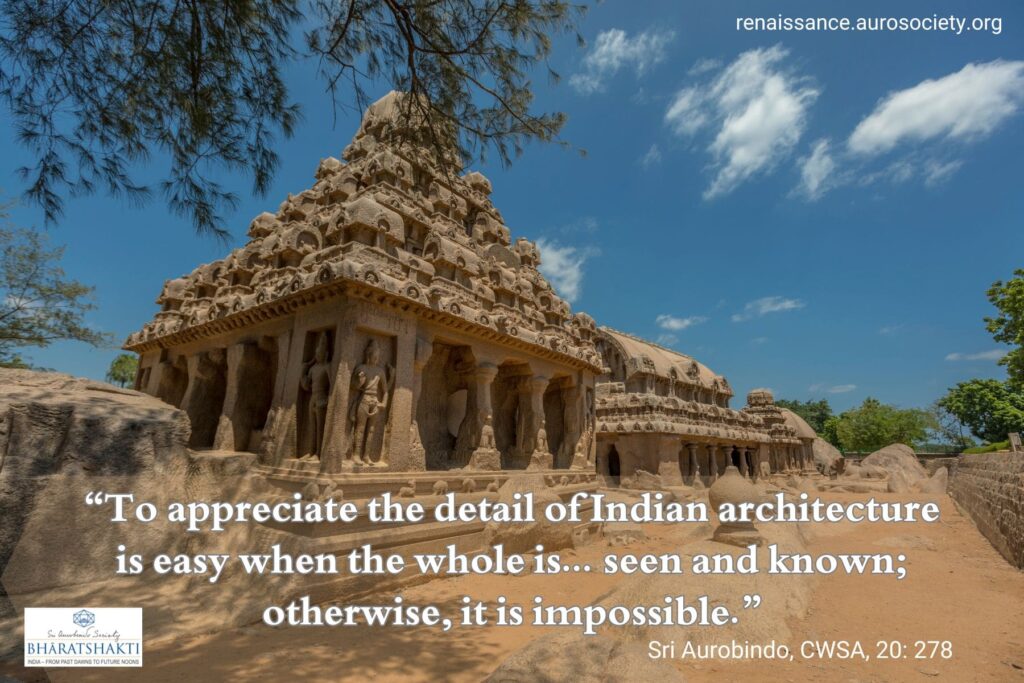

Continued from Part I

See the Temple in Its Surroundings

To appreciate this spiritual-aesthetic truth of Indian architecture, it will be best to look first at some work where there is not the complication of surroundings now often out of harmony with the building, outside even those temple towns which still retain their dependence on the sacred motive, and rather in some place where there is room for a free background of Nature.

I have before me two prints which can well serve the purpose, a temple at Kalahasti, a temple at Sinhachalam, two buildings entirely different in treatment and yet one in the ground and the universal motive.

The straight way here is not to detach the temple from its surroundings, but to see it in unity with the sky and low-lying landscape or with the sky and hills around and feel the thing common to both, the construction and its environment, the reality in Nature, the reality expressed in the work of art.

The oneness to which this Nature aspires in her inconscient self-creation and in which she lives, the oneness to which the soul of man uplifts itself in his conscious spiritual upbuilding, his labour of aspiration here expressed in stone, and in which so upbuilt he and his work live, are the same and the soul-motive is one.

A Temple Symbolizes Spiritual Aspiration

Thus seen this work of man seems to be something which has started out and detached itself against the power of the natural world, something of the one common aspiration in both to the same infinite spirit of itself,—the inconscient uplook and against it the strong single relief of the self-conscient effort and success of finding. One of these buildings climbs up bold, massive in projection, up-piled in the greatness of a forceful but sure ascent, preserving its range and line to the last, the other soars from the strength of its base, in the grace and emotion of a curving mass to a rounded summit and crowning symbol.

There is in both a constant, subtle yet pronounced lessening from the base towards the top, but at each stage a repetition of the same form, the same multiplicity of insistence, the same crowded fullness and indented relief, but one maintains its multiple endeavour and indication to the last, the other ends in a single sign.

The Oneness of the Infinity

To find the significance we have first to feel the oneness of the infinity in which this nature and this art live, then see this thronged expression as the sign of the infinite multiplicity which fills this oneness, see in the regular lessening ascent of the edifice the subtler and subtler return from the base on earth to the original unity and seize on the symbolic indication of its close at the top. Not absence of unity, but a tremendous unity is revealed.

Reinterpret intimately what this representation means in the terms of our own spiritual self-existence and cosmic being, and we have what these great builders saw in themselves and reared in stone. All objections, once we have got at this identity in spiritual experience, fall away and show themselves to be what they really are, the utterance and cavil of an impotent misunderstanding, an insufficient apprehension or a complete failure to see. To appreciate the detail of Indian architecture is easy when the whole is thus seen and known; otherwise, it is impossible.

This method of interpretation applies, however different the construction and the nature of the rendering, to all Dravidian architecture, not only to the mighty temples of far-spread fame, but to unknown roadside shrines in small towns, which are only a slighter execution of the same theme, a satisfied suggestion here, but the greater buildings a grandiose fulfilled aspiration.

The architectural language of the north is of a different kind, there is another basic style; but here too the same spiritual, meditative, intuitive method has to be used and we get at the same result, an aesthetic interpretation or suggestion of the one spiritual experience, one in all its complexity and diversity, which founds the unity of the infinite variations of Indian spirituality and religious feeling and the realised union of the human self with the Divine. This is the unity too of all the creations of this hieratic art. The different styles and motives arrive at or express that unity in different ways.

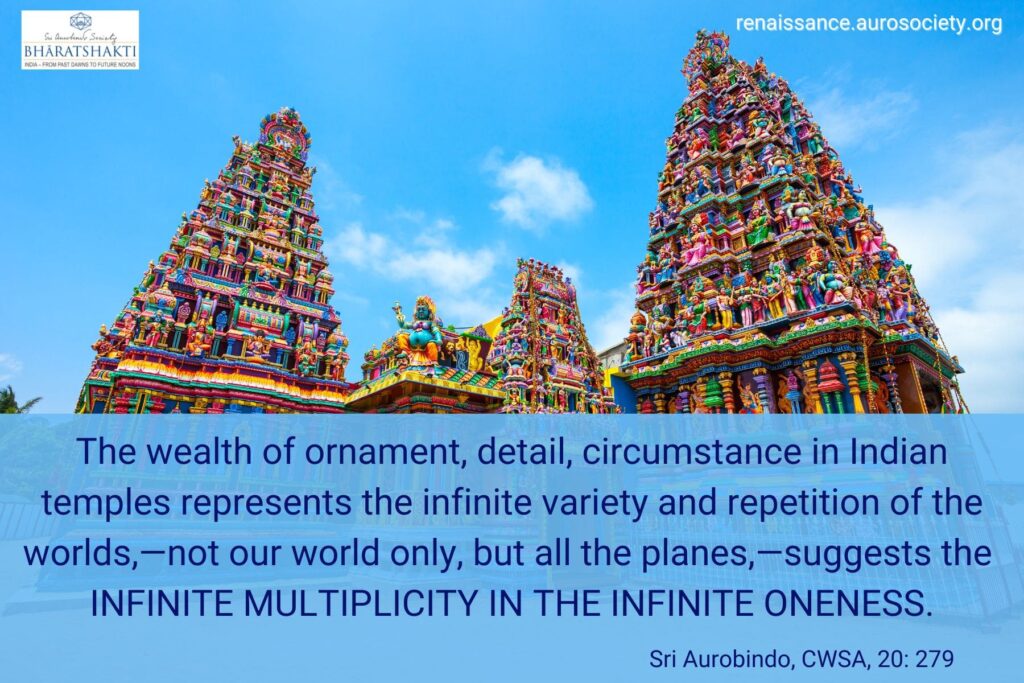

Infinite Multiplicity in the Infinite Oneness

The objection that an excess of thronging detail and ornament hides, impairs or breaks up the unity, is advanced only because the eye has made the mistake of dwelling on the detail first without relation to this original spiritual oneness, which has first to be fixed in an intimate spiritual seeing and union and then all else seen in that vision and experience.

When we look on the multiplicity of the world, it is only a crowded plurality that we can find and to arrive at unity we have to reduce, to suppress what we have seen or sparingly select a few indications or to be satisfied with the unity of this or that separate idea, experience or imagination; but when we have realised the self, the infinite unity and look back on the multiplicity of the world, then we find that oneness able to bear all the infinity of variation and circumstance we can crowd into it and its unity remains unabridged by even the most endless self-multiplication of its informing creation.

We find the same thing in looking at this architecture. The wealth of ornament, detail, circumstance in Indian temples represents the infinite variety and repetition of the worlds,—not our world only, but all the planes,—suggests the infinite multiplicity in the infinite oneness. It is a matter of our own experience and fullness of vision how much we leave out or bring in, whether we express so much or so little or attempt as in the Dravidian style to give the impression of a teeming inexhaustible plenitude. The largeness of this unity is base and continent enough for any superstructure or content of multitude.

The Eye Only a Way of Access to the Soul

To condemn this abundance as barbarous is to apply a foreign standard…. The European mind not having arrived except in individuals at any close, direct, insistent realisation of the unity of the infinite self or the cosmic consciousness peopled with its infinite multiplicity, is not driven to express these things, cannot understand or put up with them when they are expressed in this oriental art…

The objection that the crowding detail allows no calm, gives no relief or space to the eye… is urged from a different experience and has no validity for the Indian experience. For this unity on which all is upborne, carries in itself the infinite space and calm of the spiritual realisation, and there is no need for other unfilled spaces or tracts of calm of a lesser more superficial kind.

The eye is here only a way of access to the soul, it is to that that there is the appeal, and if the soul living in this realisation or dwelling under the influence of this aesthetic impression needs any relief, it is not from the incidence of life and form, but from the immense incidence of that vastness of infinity and tranquil silence, and that can only be given by its opposite, by an abundance of form and detail and life.

~ Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 20, pp. 271- 276

Go to Part I

~ Design: Beloo Mehra